MK Harb

Sundays in Beirut are empty with something more than quietness. This Sunday was no different. My grandmother, armed with flour and olive oil, kneaded the ajeen (dough) on the balcony table until it bent to her will. She flattened the center with her elbow and said: half of the city is at the beach and the other half are back in their villages, and you have the luck of being with me. Shuf, true Beirutis do not leave their home, even on Sunday. You never know who will squat in your house! My mother, sat on the couch in her green prayer gown, moved her neck left and right to end her salat and said: stop feeding Malek’s head with nonsense. We stay here on Sundays because we enjoy the calm of the city. Not out of fear of squatters!

“Uff, Nadine. You have the audacity to say this when your trip to Syria is next week. They occupied half the homes in Ras Beirut, including yours on Makdisi street and Hariri’s blood is still fresh. Allah Yerhamo, steheh!” my grandma responded.

“Khalas, Mama. We go to Syria every year. Zahi’s sister has been there for two decades, but each summer you make a fuss out of it. It’s not like Hend assassinated Hariri!” my mother replied. “Malek, go inside and call Ghaith. Ask him what they need us to bring down to Damascus,” she commanded —

I went to my teta’s room to get the handy, the phone I spent much of my life on. Twice a week I would call my friend, Maya, and we would imagine we were celebrities living in Beirut. We acted out the ego, the confidence and the drama, but we did not know what our profession was. One time she called and asked: did you send me those beautiful red flowers? The concierge just delivered them. Even though I was half asleep, I joined her act and said: No, I was sent some too. Do you think it’s an admirer?

I called Ogero and requested an international line to Damascus. After a few rings I heard an excited Ghaith say: Maloukkkk, shlonak habibi? — “Meshta’lak. I can’t wait to see you. Mom is asking what you want us to bring down from Beirut,” I replied. “Yes, I have the list here. Two packets of Tegretol 200 MG, Sara’s seizures are worse. A few Javel bleach, a couple of Pepsi and KitKat boxes, an Eastpak bag for Luna, soon in grade 10 at the German school and whatever new DVDs are available at NabilNet,” he said. “Tekram, is that all?” I asked. “Of course not. Don’t forget the McDonalds and KFC on the way. Get as many burgers as you can. We can sell them to the neighborhood boys for fifty lira per burger. And a few twister sandwiches to bribe the customs officers,” he said as he laughed. His chuckles now carried a pubescent tone, years ahead of mine. “Malouk this trip will be your favorite one. I made so many new friends in El Mazzeh and I told them all about you. Ramez, Moaz and Adam. We are hooked on this new game called Counter Strike. You get to fight like in the American war movies,” he said.

“Eh it’s popular in Beirut too, boys play it at NabilNet. Yala habibi I will see you in a week. My mom will come in and yell about the phone bill if we talk more,” I replied. When he hung up, a trepidation creeped up on me. Ghaith was my favorite cousin, the one who drove me around Qasyoun Mountain, buying me sobar (prickly pears) and shawarma from Abu El Meesh in Bab Touma. Now I had to share him and carry guns!

The next day, I woke up determined to fight. Not just for Ghaith’s attention, but the militias in Counter Strike. I gulped my Nescafe, ate the manakeesh, wore a military cap and marched over to NabilNet. Nabil, herculean built, with a face that refused to express any emotion, ate a kunefe sandwich behind his desk. He spoke with a confidence that asserted his godliness in Lebanon. Teenagers and old men alike scurried from across the country for his bootleg DVDs. Some movies like Shakespeare in Love had the best quality available, others were recorded in a cinema in Dearborn, Michigan, with theater goers walking across the screen while we watched. Once, during Vanilla Sky, I heard a movie goer eat popcorn, but I did not mind it, it was like being in the US.

“Ahlen Malouk. How was the Princess Diaries?” Nabil asked. “Oh, my mom and I loved it,” I replied. “I’m glad to hear. So, what are you in for this time?” Nabil said. “A two-hour internet card for Counter Strike,” I said, pulling out a ten thousand-lira bill. “It’s all the rage now. Making me more money than these DVDs. Are you sure you want to play with these jungleboyz?” he asked, nodding his nose to the middle of the café. It was Ramy, Omar and Jad, with their hairy legs sat in unison. Ramy was the worst of the jungleboyz, often squirting juice out of his nose to impress the girls of the neighborhood. Little did he know the girls called him Makhta, a snot. Omar, wearing his New York Yankees hat, the one he told me a million times his uncle brought back with him from Daytona Beach. And Jad, fourteen with the muscular frame of a body builder and the moustache of a bodega owner.

My recharge card was for computer 15 in a dimly lit corner that smelled like cum and sweat. The keyboards were sticky, dirtied with dust and cigarette buds. I logged in, chose “VerdunBoy23” as my username and found myself in an abandoned beige building in Havana. My fighter was already injured, he huffed and puffed in the manner of an asthmatic child. I clicked the red cross icon and brought him back to full health. Hearing the footsteps of other fighters, I ran across the stairs and ducked behind a yellow Mercedes from the eighties.

“Who the fuck is VerdunBoy23?” yelled Ramy. “No clue, but let’s take him out,” Omar replied as he switched his hat around. Weary of my imminent death, I ran to the basilica across the road, my legs shaking. I hid behind the alter and moved my focus left and right to catch any intruder. Ten minutes later I dashed out of the basilica only to hear a loud sniper shot and see my fighter collapse. “Khod! You think you can face the boys of NabilNet,” Jad yelled as he pounded his hand on the desk. “Bas wle, I will make you pay for that,” Nabil reprimanded him from across his office. I joined the yelling and said: Why did you kill me Jad? I stepped out of the dark room and continued to say: It was me. I am trying to learn the game and you guys just wasted a two-hour recharge card. “Malouk?” Jad said with a look of surprise. “Why didn’t you tell us it was you?” — “Eh Malek, why didn’t you tell us it was you? This is a game for men. You should join GTA and play as a stripper instead,” Ramy snickered while Omar laughed and blew air into his fist. Jad smacked Ramy’s head so hard his eyes jumped out of his face. “Kess emak, shut up Ramy! Malek, come sit next to me, I’ll show you how to play,” Jad said.

I watched Jad play for an hour, his arms out and his eyes sunken. The jungleboyz left the game, assuming the role of cheerleaders, drumming on the table and chanting: Jad with the goodkill. He was merciless, killing all sorts of fighters, one in Siberia, shooting him in the chest while he was camouflaged behind a tree and another in a post-nuclear Paris, standing on top of the Eiffel Tower, watching the city set ablaze, killing six men in a row. When he finished, ranking number four in Beirut, he unclenched his jaw and stretched his arms. His face was solemn like a statue, but a minute later, he exited his trance and said: ya hek ya bala. The jungleboyz jumped and Jad stood up, his large dick shaking between his baggy shorts.

That evening, I stayed longer at NabilNet, my parents were in the mountains and the jungleboyz scored more recharge cards through Omar’s Eid money. I watched their techniques, Omar skilled at ducking, Jad with a falcon’s eye and Ramy a patient observer, willing to wait out any opponent. At eight p.m., a tall boy flaunting a medallion of the Imam Ali entered the café. He asked for a one-hour recharge card and took the computer across from Jad. He looked at us and said: Shu shabeb? Anyone up for a fight?

“Umm, sure, you can join our tour. But be warned, I don’t show mercy to strangers,” Jad said.

“I don’t either,” Zaher replied.

Ramy inched closer to Omar and whispered: that’s the Shiite boy, Zaher, who moved here. His dad opened that bakery Pizza Hiba. They say they are Hezbollah spies. Ramy and Omar stayed out of the game, leaving Zaher and Jad to dual it out. The setting of this tour was vague, the fighters perched on the roof of an industrial building during a thunder storm. They shot at each other for thirty minutes, missing by a slight mark. Near the end of the game, Jad managed to shoot Zaher in the leg. Injured, Zaher ducked behind a collapsed satellite dish, clicking the red cross icon at a frenetic pace. Jad got closer and said: this will be a good kill. Omar and Ramy, noticing Nabil’s absence, stood up, drummed across the desk and sang: good kill, good kill, good kill, Jad with the good kill. Jad stood tall, wiped the swept off his face, looked at Zaher and said: coming here was a mistake. A minute later, a loud gunshot was heard and Jad, in disbelief fell. Zaher used a hand gun and surprised Jad with a sudden death. The game ended and Zaher was crowned king of NabilNet for the day.

The jungleboyz went quiet, packed their bags and shut off their computers. Zaher broke the silence and said: good game men. Anyone up for some shisha to celebrate?

“Nfokho,” Ramy yelled. “Come on boys, let’s have some ice cream away from this twat,” he continued to say. Zaher fiddled with his necklace, looked at me and said: are they always jerks?

“Ramy more so than others,” I replied. His sorrow-filled eyes saddened me, but in that very moment I knew that to be a great fighter I had to learn from him, not Jad. “Listen, I have a proposition for you,” I said. “I want to train in combat and you have what it takes. I have a tournament coming up. How about you teach me?” — “What’s in it for me?” Zaher asked. “I will pay for your recharge cards for a week,” I replied. “Add chips and two cans of Pepsi and we have a deal,” he said. “Manak hayen, yes, we have a deal,” I said. His face wore an impish smile and he replied: see you tomorrow.

At five p.m., I was at NabilNet. I bought two internet recharge cards, two bags of Fantasia chips and two cans of Pepsi. I took the corner computers again, away from the jungleboyz and waited for Zaher’s arrival. Ten minutes later, he walked in, ginger curls dangling from his head, delicious pecs imprinted on his shirt and long black lashes that caressed the air around him. He sat with his legs wide open and said: did you log in yet?

No, I haven’t.

Well before you do, you need to change your username.

What’s wrong with VerdunBoy23?

It sounds like a girl’s username. And we are men here! Pick a name that will strike fear in the heart of your enemies. Like Jaafar!

I went quiet for a few minutes and workshopped names in my head until I found it: Abdulrahman’s Sword. Inspired by my uncle Abed, a brutish man who after a few glasses of cognac spoke with a voice so loud it woke our neighbors. Zaher winked and said: now we’re talking. We logged in to our computers and got transported to a dusty Fallujah in the midst of a busy spice bazaar. Zaher stood behind one of the vendors and I stood at the entrance of a residential building. The floor was cracked, riddled with damaged rubber tree plants, a broken office chair and a collapsed frame of The Righteous Names of God. A woman wearing a green hijab hid her son behind her back. “Hey are you okay?” I asked. She did not respond and just breathed. Zaher squeezed my hand and said: focus and follow me. We ran towards an empty square surrounded by four palm trees, ash brown in color. “Don’t move,” he yelled. I heard gun shots and saw a man falling from behind one of the palms. Zaher elbowed me and said: stay behind me, I will protect you until you are strong enough to fight.

For a week, Zaher and I camped around computer fifteen and sixteen, inhaling and exhaling together, sharing Unica bars and Fantasia chips until at one point we found our hands inside the same salt and vinegar bag. Zaher laughed, took a few of the chips out and handed them to me. The jungleboyz ignored us except Jad who assailed me with his eyes, angry at my betrayal. Though I did not care. Zaher was all I needed. He taught me the thrill of the fight. One evening, he played for four hours straight, the boys pouring in from across Hamra and Verdun to witness his marvel. Nabil, never one to miss an opportunity, charged each one of them a watching fee of five thousand liras. I sat next to him, opening his fourth Pepsi can as he shot every fighter he came across. His rage was endless. He entered the fifth hour, it was getting dark, the boys tired from standing, left one after another, gifting NabilNet to Zaher and I. Catching a breath, he looked at me and said: feed me some chips. I reached for the cheese-flavored Fantasia and put some over his tongue and bits of my right finger entered his mouth. I repeated this act, until Zaher, satiated, said: khalas, thanks habibi. We neared the end of the game, he was overcome with excitement, his body hotter than the modem next to us. His right leg shook with an intensity that caused our chairs to move as if we were in an earthquake. I closed my eyes and took in this euphoria, shaking along with him. A voice then woke me up from my trance, it was Zaher yelling: EHHHHHH. His elated tone carried a feminine inflection within it. He ended the fight and moved his index finger across the screen, counting the nationwide rankings: Zaher number two. He stood up, championed his arms in the air and looked around the café only to realize it was just us and Nabil, having his falafel sandwich. I opened a Unica bar for him and said: who cares about these assholes?

He walked over to the door and yelled to the air: exactly, who cares about these assholes! He then looked at me and said: I’m glad my best bro was here with me. Hearing him say that, my heart jumped out of my chest. To celebrate, we walked over to Mahmaset Rabea, one of the few stores that imported green apple Airheads from the US. We sat in the parking lot of my building, under a Jacaranda tree, the leaves of which filtered out the light from the streetlamps, revealing red veins swimming inside Zaher’s green eyes. He ate the last of the Airheads, licking his tongue and making a loud bang sound. He fist bumped me and said: it’s time to find a service (taxi) home. “It’s not safe at this hour,” I said. “Oh please, I used to take taxis from Bent Jbeil to Beirut at the age of ten. See these guns, they’re all I need,” he said while he kissed his right bicep. I wished I could kiss them too.

Knocking my house door, teta greeted me with her inquisitive eyes, covered in a fume of double apple shisha. “Sorry I’m late. I didn’t realize the time,” I said. “I won’t tell your mom if you won’t tell her I’m feeding the snake,” she said, a term she loved to use when she smoked shisha. “No humidity tonight, thank god,” I said. “We are lucky to have this balcony. My mother, allah yerhama, was always in heat in Beirut. She came from the north and prayed that God shelters her from the humidity. And since that prayer, the breeze never left this house,” she said while smoking her shisha. “Listen, I’m happy you’re enjoying the summer with new friends, but I don’t want you to hang out with this Zaher kid so much. Jad’s mother told me about him,” she continued to say. “Why? He’s sweet and polite. And he’s teaching me some games,” I replied.

“I’m sure he is. But you know ever since Rafiq Al Hariri was assassinated, the situation is tense. And I heard from Latifa who heard from Abu Mahmud that Hezbollah is funding his father to open a bakery in our neighborhood. They are spies. Be careful,” she said while changing the coal over her shisha. A bit of the ash fell to the ground, she ignored it and said: I’ll clean it later.

“You’re watching too many movies, teta,” I replied. “Malek, you did not live through the war. Think about it. Now it’s time for bed, go inside and close the balcony door behind you,” she commanded. Sitting in bed, watching the ceiling fan spin out of control, the flowers carved on it dancing like dervishes, I replayed feeding Zaher chips in my head. I left my grandmother’s words on the balcony, what did she know!

It’s three days till Damascus, I was happy to see Ghaith, but sad to leave Zaher. My parents went to the mountains to clean and lock our house and my grandma went to her sister’s home in Zareef. Heading down to the taxi she yelled: Why can’t Sumayyah come here? That part of Beirut smells like Baharat (seven spices)! At five p.m. I was at NabilNet waiting for Zaher. He came in fifteen minutes later, this time his smell proceeded him. It was a strange fragrance, as if one drowsed a field of lilies with gasoline. “Nice perfume,” I said. “Man, this is all the rage. Fahrenheit by this brand called Dior. I know this woman Zainab who sells unbought testers from the airport duty free. Only fifty thousand liras!” he said, happy I noticed his scent. “I’ll buy you one next time I go to her shop,” he continued to say. This time I could not hide my explosive smile as I said: hey listen, my parents are out of town till ten p.m. You want to come over? We can take a break from Counter and watch the Comedy Channel. Why not? Do you have a shisha at home? Eh, my grandma smokes, but I don’t know how to make it. Bro, I’m the argileh king, I’ll make it.

Entering the house, Zaher took his shoes off, put them aside and went into the kitchen. He maneuvered his way around it with ease, as if he had been here many times before. I watched his feet dance around our blue and white terrazzo tiles and his long arms reach for the cupboards, conjuring an afternoon snack of Lays chips, janarek (sour green plums) and Pepsi. “You can call me Argaljeh,” he said. “I love calling you Zaher,” I said with a muffled tone. When he finished his shisha operation, he smiled and said: let’s smoke it on the balcony, it’s nicer with the breeze. I loved that he indulged himself in the manner of an Ottoman prince.

Sitting on the balcony, I was faced with my grandfather’s sepia portrait, with his almond-shaped eyes and his olive-colored suit. He had a black line painted over his head, a sign that someone was martyred. Though he was no martyr, in fact he was an infamous womanizer, who died in the arms of a prostitute who lived near the port of Beirut. Her name was Warde and she wore silk whenever she saw him. My grandfather spent three nights a week at Warde’s house, returning home, with a smile cast in iron, and smelling of rose water. My grandmother could not handle that he died in the arms of his mistress so she lied and added the black line.

Zaher, sitting under my grandfather, smoked his shisha, pursed his lips together and blew large circles of smoke. At one point, he put his finger in the middle of a circle, bringing it back and forth, until the smoke dissipated. Watching him, the tingling sensation in my groin returned. My ears turned red and I felt as hot as Zaher’s computer during a game. “Come sit next to me and try it,” Zaher said. I jumped across to the couch with an attempt to hide my erection. “Ntebeh, you might break your grandma’s shisha,” he said while laughing. I sat quietly next to him for a few minutes, the pipe and its burly sounds between our legs. I broke the silence and said: I’m glad we became friends. “We’re not friends. We’re brothers,” he said, pressing his hairy arms around my back. I saw an erection coming out of his shorts and it was the sign I needed to know he’s comfortable. I reclined my head on his chest while he played with my hair and smoked his shisha, sending a double apple cloud out to the streets.

We stayed like that for ten minutes, in solitude like a Beirut Sunday, until Zaher, noticing my mother’s orange Nokia phone, said: damn is that a Nokia 5200?!

Eh, it’s my mom’s. She leaves it here when she goes to the mountains, in case I need to reach her. There’s no landline there.

Can I see it?

Sure, we can play Snake if you want.

Zaher reached for the phone, his face a hall of excited impressions. I helped him slide it up and we opened the game. He played a round of Snake, called my house phone as I answered and said: hello you’ve reached KFC Rouche and laughed.

I watched him play, mesmerized, but I wanted to get his attention again. “You can also send pictures to others via Bluetooth, my mom does that all the time,” I said. “Here, let me show you,” I continued to say.

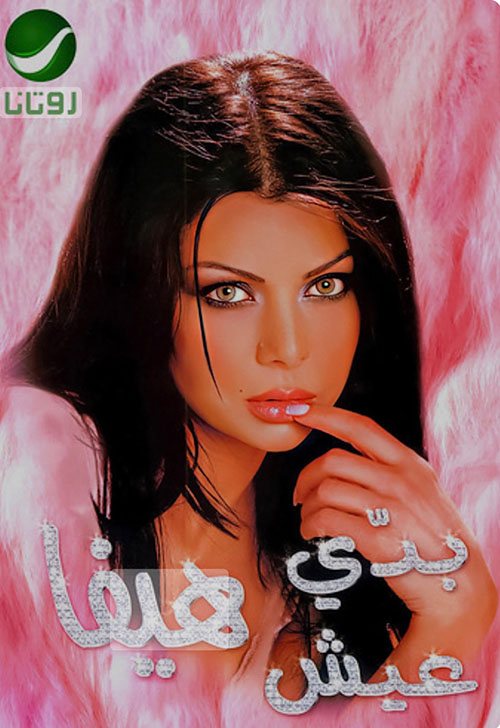

I opened the Bluetooth gallery and when I clicked on the latest photo, my heart dropped to my knees. It was a meme of Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s spiritual and political leader, superimposed on Haifa Wehbe’s album cover, Bady Eeesh. Haifa, wearing pink silk, posing in a bout of ennui, with her right index finger in her mouth. Except this time, it was not the face of a seductress, it was the face of Hassan Nasrallah floating over her body.

Never mind, I said, I don’t think it’s working.

What’s wrong?

Nothing, ensa.

“Shu fee,” he exclaimed as he stole the phone and opened the gallery. It took him a minute to take it in and then he looked at me and smacked my chin with the phone, closing the slider. He stood up and said: you are just like those assholes at NabilNet.

It’s not me! It’s my mother’s phone, Zaher come on!

Fuck you. You were just using me to learn Counter and fit in with the rest of them.

He rushed to the door to wear his shoes.

“Zaher please I’m sorry,” I yelled.

He stood at the door and said: if you ever come near me again, I will break your legs. He smacked the door causing my neighbor Nada to open hers and yell: Shu fee!

I went back to the balcony, still smelling of double apple, cursing my luck. A bird came out of my grandma’s clock announcing it was ten p.m. My parents were almost home! I cleaned the shisha to the bone, took out the garbage and rubbed a few of the naphthalene balls on the couch.

When my mother arrived with a dust and drab look, she said: yih yih, I need a shower and rushed to the bathroom. I was relieved she did not have time to take notice of the house and I went to bed, with an anger festering towards her and her memes.

The next day, I camped out at NabilNet for hours. Sequestered in my dark room, I watched the door from the corners of computer fifteen and awaited his arrival with a bag of Airheads and Pepsi. An hour passed and so did the jungleboyz, who drenched the floor with their wet bathing suits, returning from their swim at the military beach. “Ya kleb! Go outside now. You think you can just come and play with your wet clothes like monkeys! La barra.” Nabil yelled. At eight p.m., during the call for prayer, I accepted my defeat and walked home. The athan sounded more melancholic today, slow and elongated pronunciations, like the prayer recital for the deceased. Entering the house, my grandma greeted me with a plate of lahm b ajeen. “Have some good food before you go to all that fat and lard in Syria,” she said. I had four of them, oily and crispy, with the taste of the minced meat waltzing inside my mouth. My grandma did not bother asking what happened, though reading my facial expressions, she assumed Zaher and I were no more and it made her happy.

During my last days in Beirut, I avoided walking by Pizza Hiba, taking the longer route to Hamra up the Koraytem hill. Zaher stopped coming to NabilNet, which made the jungleboyz happy, Ramy saying: back to southern Beirut where he belongs. If only they understood his beauty and the way he embraced me.

That summer in Damascus, Zaher’s words stayed with me: shift left. Duck. Walk slower. Shoot from the right side of the eye. Don’t hide behind cars. His training led me to the top five fighters list in Damascus, my cousin starstruck, showed me off in front of his friends. “I told you he was Kafou,” he said. Soon after, I forgot about Zaher. A few months later, playing at NabilNet, the jungleboyz, now my cheerleaders, applauded and drummed for me: Malek with the good kill. Jad stood next to me, proud that I was back in their terrain, and watched as I neared the end of the game. I saw the last remaining fighter, hiding behind a car, his gun peeping. “Amateur,” I shouted. As I pointed at him from across a town square, he ambushed me, shooting from beneath the car. I fell, the jungleboyz yelling: nooooooo. Jad comforted me and said: it happens to the best of us. I looked across the screen, curious to see who he was and the name said: Zaher.