London-based writer Sophie Kazan Makhlouf travels to Saudi Arabia to take in a citywide festival that may have forever changed the cultural landscape of Saudi Arabia.

The experience of curating Noor will fundamentally change my practice and the way I think about presenting art in a public space. I can no longer think of light as mere a tool to illuminate artwork.

Sophie Kazan Makhlouf

As night falls in Riyadh, busy squares, parks and skyscrapers pulsate with light installations, video projections and bright sculptures. Noor Riyadh — Light Riyadh — is the largest light art exhibition in the world. For two weeks, the third iteration of the Saudi capital’s citywide light festival, The Bright Side of the Desert Moon, draws together work by over 100 international and Saudi artists. It turns a major metropolis into a gallery without walls, the event’s tagline that suggests broad inclusivity, the overarching mission of this impressive, international light art showcase. Curated by Pedro Alonso, an independent curator from Boston, the Paris-based lead curator Jérôme Sans, and Alaa Tarabzouni and Fahad Bin Naif, both architects and curators from Riyadh, Noor Riyadh is one of two annual art events organized under the umbrella of the Saudi government’s public art initiative, Riyadh Art.

The festival, which includes an indoor exhibition, is centered around three main outdoor hubs. Set against the Wadi Hanifah waterway is Khaled Makhshoush’s Untitled, 2023, on a massive LED screen, The Saudi artist uses 8-bit/32-bit pixelated graphics of the kind used in video games, a medium that was the artist’s gateway into art, to depict the far bank and a bridge. This is the view that the screen seems to be hiding and yet the artist has added creative “glitches.” Makhshoush’s light-hearted distortion of reality forms the basis of his playful approach to contemporary Arab urban settings, which has become his trademark. He utilizes the light of the screen to give the viewer the feeling of looking through a camera lens or the frame of a mirror.

Also in Wadi Hanifah is Tree House, 2019-2023, by Palestinian artist Ayman Daydban who lives and works in Riyadh. Tree House’s massive installation is made up of two long walls and a ceiling made from cutout sheets of wood. These are layered to create a complicated patterning of shapes that apparently re-examine national narratives and the framing of nationalities. At night, these become a “tableaux vivant” which can be made out by the viewer, thanks to bright floodlights that shine through the space and create shadows along the floor.

In the Noor Riyadh hub at Wadi Namar, a dam that has recently been made into a public park, many of the artworks and international artists depict scenes related to natural environments; the local desert landscape and lusher tropical or North American spaces, conjured up in colorful projections or illuminated installations. Though it is dark, nature seems to be everywhere. Monira Al Qadiri, an artist born in Senegal, is a citizen of Kuwait and lives in Berlin. She combines the sculptural in Monument, 2023, and a projected contextualization of the Jinn tree and its desert surroundings for The Guardian, 2023. This is a tributary film which explores the tree’s imagined powers over mankind.

Wadi Nimar’s rolling sand dunes can also be evocatively experienced through Hana Almilli’s Journey through the Ripples of the Sand installation. Almilli, a Saudi multimedia artist, textile designer, and poet, has created a Perspex enclosure that encircles the viewer in a sensation of light, sound, and fine, hanging textiles.

Much thought has gone into the visitors’ experience of the festival. At Wadi Hanifa and Wadi Namar, a team of young docents waits in front of the artwork to explain, explore and enlighten passersby in Arabic or perfect English. These young men and women had been well briefed by museum professionals to enquire about visitors’ perceptions and gently offer possible interpretations. It is extremely telling that Noor Riyadh places emphasis on and encourages visitors and local people alike, to learn about art, listen to different ideas and intentions and, in turn, verbalize their own impressions without embarrassment.

An artwork that runs along most of the Wadi Namar festival location is A Wild Kingdom, 2023, by the American artist and curator Diana Thater. An immense video installation spans the 400m long cliff face of the riverbank and rises up 30 meters from the ground, dwarfing much of one side of the waterway thanks to multiple, high-range projectors from across the water. These showed natural locations from a range of colorful global locations, including footage of wild animals and birds. However, as the name suggests, the projected work is also intended to impress upon the viewer the fragility and transience of nature.

Also unexpected along the far water-bank is Aziz Jamal’s The Whites of Their Eyes, 2023. A site-specific projection of the eyes belonging to the Saudi multidisciplinary artist quietly stares at the viewer from across the water. Slowly, more eyes are added until a crowd of on-lookers creates an eerie presence in the darkness. According to Jamal, the work evokes the local legend of Abu Fanous, a sly, mythical character that comes out at night to mislead desert travelers.

At the far end of the park, set beyond a dusty path and rock face, is a massive, multi-sensory steel sculpture, Chris Levine’s Molecule of Light, 2021. It measures 25 meters high and seems to pierce a crimson globe of light containing a meteorite at its peak. All around this hangs an almost foggy haze, with lasers tracing the ley lines of the wadi’s surrounding rock face. A sound frequency is set to affect the viewer’s bioelectric state and the work itself seems to give out a magical charge of light and color. The combination of light and sound is dreamlike and the light is apparently synchronized with the earth’s rotation.

The artist tells me, “For me lasers represented a very pure form of light, single wavelengths, of an energy we take for granted but is fundamental to the way things work in our physical realm. There’s a spiritual dimension to the work and that’s what resonates with us all.”

Another important consideration for the light art festival is the ability of works to interact not only with adults but also with young people and children in the city. “The youth and Saudi energy impacted the show,” exhibition curator Pedro Alonso cites, for example, the family-friendly works in Noor Riyadh’s third hub, Salam Park. Friends with You, the Californian duo’s colorful inflatable installation, Nature’s Gift, 2017, in the park, invites visitors of all ages to interact with the spaces around the massive objects, and this underlines the importance for the artworks to be open to all. Visitors, young and old, are invited to lose themselves in a surreal and tactile forest: tall, multicolored poles covered in luminous hair or fur by the Icelandic artist Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir a.k.a. the Shoplifter.

Drones

The grand opening for the Noor Riyadh took place in the city’s business district (KAFD) with Desert Swarm, a massive floating installation made up of 3,000 drones by the Dutch company, Drift. Set to a rising piano soundtrack and shown at least once every night during the festival, Desert Swarm lasts over 12 minutes as it explores the intersection of technology, nature and music. The spectacle is graceful but also a little frightening as buzzing drones amass overhead. According to the German company, Statista, the median age of Saudi Arabia’s population was 29.2 years old in 2020. The way in which tech is included seamlessly into so many of the Noor Riyadh’s artworks and activities is surely a sign of things to come.

The sheer range and quantity of artworks in the festival are remarkable, although upon my return friends and colleagues have been quick to call Noor Riyadh “art-washing and cultural diplomacy.” They have also been surprised to see my countless photos and descriptions of enormous artworks by international artists and to learn of the city’s enormous investment into light art. Surely investments into all or most contemporary art are to be encouraged?

The festival has been extremely successful in its mission to draw creative talent to the Saudi capital, while also ensuring that the focus remains on art and creativity rather than difference and distortion. The aim is to put the city on a cultural and artistic map, allow the work of Saudi artists to engage with local residents in a new and interactive way. So yes, this is an orchestrated event, but surely large events globally, organized by a government entity or corporation would necessarily need to set parameters and guidelines to ensure that the event could be pulled-off successfully. The artworks and installations at Noor Riyadh provide an opportunity for local and global visitors to gain an understanding of light art, explore its limitations and also discover both Saudi and global artists working in the field.

After showing me around many of the works in Wadi Hanifah and giving me insights into works around each of the outdoor locations, curator Alonso admits, “The experience of curating Noor will fundamentally change my practice and the way I think about presenting art in a public space. I can no longer think of light as merely a tool to illuminate artwork. Moving forward,” he says, “I will be pushing artists to integrate light into their work whenever possible.”

Indoor Art Exhibition

The festival also includes an indoor exhibition located in JAX, the city’s growing contemporary art district. Refracted Identities, Shared Futures, curated by two Noor Riyadh veterans, the public art director Maya Al Athel and the art director of Desert X, Frieze Projects and senior curator of MoMA PS1, Neville Wakefield, focuses more specifically on peoples’ interactions with light and the lived experience.

The exhibition is divided into three consecutive themes: Cosmos, Temporality and Connectivity, though all the works seem to overlap in their considerations of location and time. What is particularly exciting about this exhibition is that it contains work by a majority of Saudi artists (17 compared to 13 international artists) though the variety and scope of many of the artworks in the dark, windowless gallery spaces is like walking through a dream!

Artist Abdelrahman Elshahed trained as a calligrapher and taught Islamic art and Arabic calligraphy at the Holy Mosque of Mecca, before studying architecture. This respect for the written word and the concept of space and place making can be identified in his exploration of spiritual geometry for Light upon Light, 2023. The work is based on references to the light of God in the Qur’an and it is mounted on the wall though, according to Elshahed, the work can be turned or read in four axial directions.

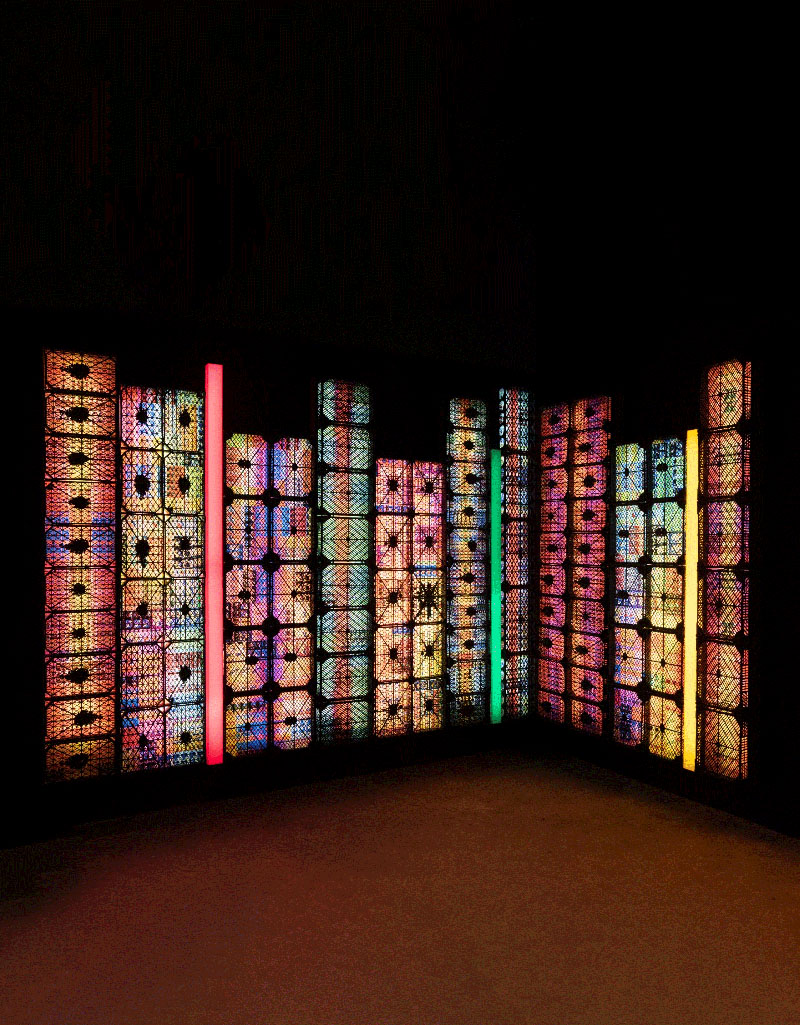

In another room, Rashed Alshashai’s Brand 16, 2022, is part of a series of works that comment on consumer culture. Beautiful black, framed light boxes resembling stained-glass windows are mounted on the wall. On closer examination, the window-shaped designs reveal themselves as colorful brand wrappers and consumer packaging that appear to glow, suggesting an unhealthy over-reliance of unethically-made and mass-produced items.

Art that literally shines a light on (and around) Gulf culture and traditional customs is Badiya Studio team’s Symphony of Light, 2023. Badiya Studio is Saudi national Mohammed AlHamdan a.k.a. Warchieff and Mohamed Al Kindi from Oman. Symphony is a performance art set in a dark room, where six, traditional drums are played loudly by three drummers with synthesized strips of light. The lights appear to dance and move across the room to the music. The effect is rhythmic and also mesmerizing. Since the musicians’ performance times are limited, audiences are allowed to interact with the installations and create their own lights in the room by playing on the drums during the exhibition.

One of the effects of the light medium is that artworks throughout the exhibition are often contemplative. An example, which draws much commentary because of its powerful use not only of light, but also of shadow is Conrad Shawcross’s Slow Arc inside a Cube XI, 2020. This part of a series of light art installations by Shawcross is based on the chemist Dorothy Hodgkin’s research on crystallography and the molecular structure of insulin. A diamond-shaped cage, made up of layers of metallic mesh, hangs in the center of a room, swaying gently as pea-sized lights move inside the shape, casting shadows onto the walls. An intricate framework of geometric patterns appear to glide around the room in an other-worldly dance.

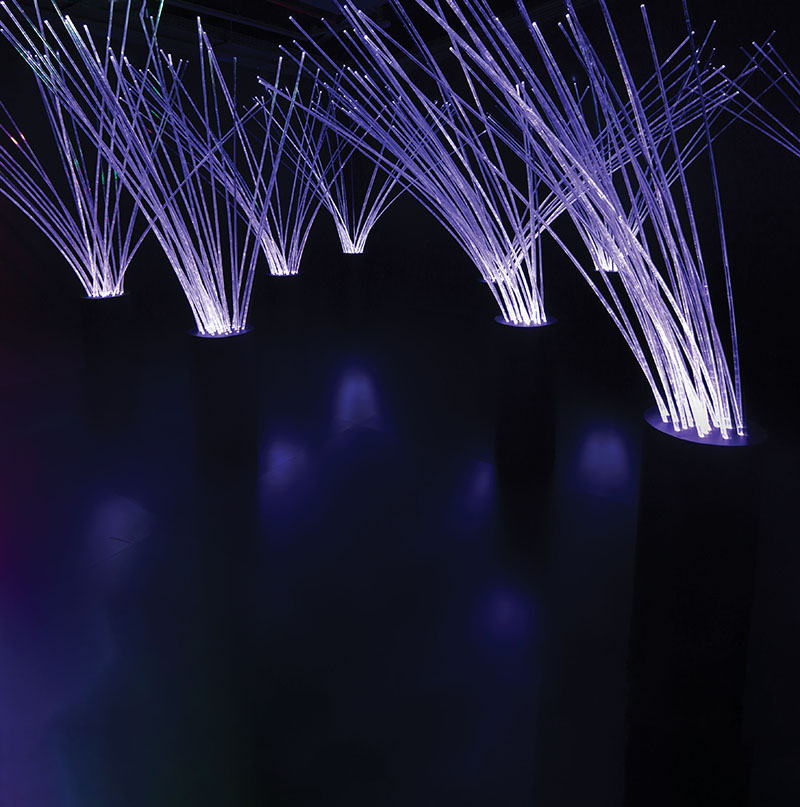

Jeddah-based artist Bashaer Hawsawi’s Let’s Play Well, 2023, fills another room. It is an installation in which jets of LED lighting recalling children’s fiber optic light games appear to spring out of short platforms or vases placed around the dark space. Hawsawi tells me that she loved playing with these lights as a child and that the installation focuses on memory.

“I am encouraging viewers to think back to simple pleasures, slower and more lighthearted times,” she says, as we pick our way carefully around the light sprays in the quiet darkness.

The works in the Noor Riyadh exhibition all focus on individual themes and forms of artistic expression that can be specific to the artist’s country but more often, they relate to ways of thinking, feelings of sound, movement and interaction with light itself. I agree with Noor Riyadh’s Project manager, Saudi’s legendary interior architect and designer Nouf Almoneef who believes, it is “those moments of awe and inspiration” that make the festival so special.

An important mention should be made of an installation located in a studio just outside the JAX exhibition, entitled Absent Sky, 2023 by artist Muhannad Shono. In Absent Sky, a black, shapeless ceiling hangs over a luminous, white room. Gradually the ceiling comes to life above the viewer’s head, and it appears to descend and hover in a tantalizing and unexplainable, moving dark mass. A native of Riyadh, Shono is well known amongst Gulf art enthusiasts, particularly since his Teaching Tree, 2021 installation featured in Saudi Arabia’s Pavilion at the Venice Biennial last year. It explored the creation and source of (national) narratives and storytelling.

Nearby, British-Nigerian artist, Yinka Lori designed skate-able sculpture park that combines skate, art and design in front of Riyadh’s King Fahad National Library. The space is floodlit in bright colors and dedicated to the local skate community, who are presumably, due to the heat of the day, most active at night. The installation’s vivid rising shapes create an environment, suited to the zany geometric white casing of the library building’s backdrop.

Permanent public art is crucial to Riyadh Art’s vision of transforming the city into a gallery without walls and the Noor Riyadh team are keen to let me know that the festival is also accompanied by numerous outreach programs and artistic interventions. I am concerned that so much of these beautiful site-specific artworks must be removed and will be unsustainable in terms of maintenance, over long periods of time. Almoneef reassures me, “Some of the works exhibited during these events will go on to become part of Riyadh’s permanent collection. They will be showcased in public spaces across the city, incorporating art across new urban environments.”

Before I leave Riyadh, I ask Pedro Alonso what it’s like working with a Saudi audience. “It is simultaneously very different from anywhere else I had worked before but also strangely familiar,” notes the curator. “Particularly the desert landscape and family-oriented society reminded me a great deal of Mexico, my home country. The media tends to focus on our differences, when in fact it is the similarities that are most fascinating.”

The Noor Riyadh 2023 Festival ended last week. The Refracted Identities, Shared Futures Exhibition, at JAX runs until March 2, 2024.