One performance traverses 400 years of history, examining the often overlooked colonial origins of climate change, reconnecting with indigenous knowledge and wisdom across the global south, and highlighting the responsibility humanity has to one another across borders.

Hassan Abdulrazak

This summer, theatre in the UK’s Shubbak Festival, “A Window on Arab Cultures,” has a global outlook, including several productions concerned with the earth.

According to French philosopher Alain Badiou, the world can be divided into “societies with theatre and others without.” He argues that theatre has “generally elided from Islam,” and qualifies his exception with the word “generally” to account for “the sacred dramas through which Iranian Shi’ism conferred Presence upon its founding martyr.” What Badiou ignores are oral storytellers offering dramatic interpretations of Islamic material who, according to Prof. Marvin Carlson in his book Theatre and Islam, were recorded as early as 650, less than 20 years after the death of Prophet Muhammad. Whether you are on team Alain or team Marvin doesn’t matter much today, as it is undeniable that theatre is alive and well in the multicultural, multifaith Arab world, where Islam originated.

This is evident if you attend Shubbak, the UK’s largest biennial festival of contemporary Arab culture, bringing both international acts as well as UK homegrown talent. In addition to theatre, it features dance, visual arts, literature, music and film.

“Why do we do art?” is the question Alia Alzougbi, co-artistic director of the festival along with Taghrid Choucair Vizoso, has been grappling with as the pair put the finishing touches to this year’s program. For Alia the answer is engagement in a post-Covid world with seismic issues such as climate change, misogyny, racism, and other topics that are of global concern. What the festival offers British audiences is the chance to look afresh at these subjects through an Arab lens.

As a playwright, I have participated in past editions and will have a reading of a new play of mine in this year’s festival. In this article I will be giving you a flavor of the theatre performances you can expect to see.

Act 1: The State of the World

What the Dog said to the Harvest is a fierce performance that fuses opera, dance, spoken word and film into a compelling show about climate justice. Directed and composed by Jasmin Kent Rodgman, and written and co-directed by lisa minerva luxx, the work has been devised through rigorous research and the contribution of activists and grassroots networks across Syria, Lebanon and the UK.

Rodgman’s haunting score and luxx’s poetic oral essay traverse 400 years of history, examining the often overlooked colonial origins of climate change, reconnecting with indigenous knowledge and wisdom across the global south, and highlighting the responsibility humanity has to one another across borders.

Set within a documentary film and sound installation with stark yet striking choreography and howling musical movements that travel across the performance space, we are introduced to luxx’s visceral critique of Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes whose writings underpin Western science and philosophy, moving into testimonies of those in the global south for whom climate change, caused in part by the imperialism of the West, is a current reality rather than a future prospect (and one that is now already on the West’s doorsteps). The performance also cleverly and subtly draws parallels between the violence man has enacted on the planet and the violence white men have enacted on the global majority.

Woman at Point Zero is a multimedia opera inspired by Nawal El Saadawi’s seminal novel of the same title. Composer Bushra El-Turk was deeply affected by the novel and knew she wanted to adapt it as an opera. The novel tells the story of Firdaus, a woman imprisoned for the murder of a man who awaits execution. She confides in a researcher (based on Nawal) about her life story which chronicles systematic abuse by men, some of them relatives, leading to a life of sex work. However, the woman is far from a mere victim, having some agency over her life and choices. Bushra was keen to examine the question the novel poses of whether one can be freer inside a prison than outside it by having that reflect in the music. “When a melody is restricted in its freedom of movement, all other musical parameters suddenly become much more important. What happens between the notes is the most important thing to me. There is freedom to be found there.”

Director Laila Soliman working with writer Stacy Hardy has updated the story to bring it closer to the present. Laila describes the opera as “docufictive” as it intersperses Nawal’s story with documentary audio fragments about Egyptian women prisoners made by filmmaker Aida el Kashef. Firdaus becomes Fatima in the opera and her interlocuter is Sema, a filmmaker. The interaction between the two women provides the dramatic engine for the opera which, while remaining true to the Egyptian roots of the story, still manages to resonate beyond the borders of that country as it examines the power dynamic between women and men. As Laila Soliman puts it: “In Europe misogyny is less in your face but it’s still there.”

IMEDEA is also about a woman killer, one of the most famous in literature. In Sulayman Al Bassam’s version, Medea is an outspoken Arab actress who lives in Corinth, a secular European state, and clashes with its ruler Creon as well as her husband Jason over the plight of refugees fleeing to Corinth who are now treated as “illegal migrants.”

“Medea is both the fugitive migrant and the barbarian outsider,” as Sulayman describes her to me in an email exchange. “When she is confronted with the oath breaking hypocrisies of Jason and the punitive social mores of Corinth, she is led to take terrible vengeance on the society around her.” Sulayman was drawn to the story because “Medea, in addition to being an exploration of rebellion against forms of colonial patriarchy, is also a brilliant study of the acrimony and agony of divorce.” Medea is played by Sulayman’s long-time collaborator, the Franco-Syrian actress and singer, Hala Omran, last seen on the London stage in the critically acclaimed Two Palestinians Go Dogging, in which she brought a calm intensity to the role. IMEDEA unnerves with its brutal imagery and musical score performed by Lebanese electro-acoustic duo, “Two, Or the Dragon.” It exposes the gap between self-proclaimed European ideals and the reality of the policies perpetrated by European governments.

A critique of the West and its treatment of Arabs are vital and necessary. However, this should not come at the expense of dealing with problems in the Arab world itself. Colette Dalal Tchantcho is a Kuwaiti-Cameroonian actress and theatre maker whose show Dreamer is a semi-autobiographical performance about three Black women in Arab society. It confronts the choices and challenges they face as they navigate a world that can be hostile as well as joyful. Growing up Black Arab in Kuwait, Colette felt like she didn’t have much agency in comparison to, say, African Americans she watched on TV. Eventually she left Kuwait and settled in London. “In Kuwait I was as Cameroonian as my father. However, in London, with so many black African diasporic communities, I couldn’t relate. I didn’t speak French very much, I had been to Cameroon a handful of times and so I was considered Arab. I found myself saying I was Kuwaiti or ‘Black Arab’ more to reflect my mother tongue, how I grew up, my traditions, favorite food.” Despite a successful acting career, appearing in shows such as Domina (2021), The Witcher (2019) and Dangerous Liaisons (2022), she has not been cast yet as an Arab. Dreamer is a corrective to this invisibility. It reflects a varied, textured Black experience that has long been silenced and hidden away.

Act 2: Blurred Identities

In past editions of the Shubbak festival, there was often a clear delineation between theatre artists living and working in the Arab world and those in the diaspora. In this year’s festival that distinction is much more blurred. The work of many of those featured draw on influence from many quarters and speaks to multiple communities. In the case of the next artist, the work originated in one place, traveled to another and returned in a different form.

Hannah Khalil is one of the most prominent and prolific playwrights working in Britain today. She has had tremendous success with her play A Museum in Baghdad, produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2019, and was the first playwright to have three plays almost simultaneously at the Globe Theatre last year. In 2016, Her play Scenes from 68* Years had a sold out run at the Arcola Theatre and helped to cement Hannah’s reputation.

The * in the title denotes the number of years since the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. As the title implies the play presents scenes, some connected, others not, that illustrate the life of Palestinians. Its power lies in not being didactic but rather forensic in its examination of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Since then, Hannah has reworked the play for a production in Tunisia that the Shubbak festival is now bringing to London. “This new production is very exciting because it’s really a new play!” says Hannah. “It has six new scenes that I wrote specifically for this version, and those scenes speak to the Tunisian experience of uprising and protest. It is performed in three languages: Tunisian, French and English, and has a mix of Tunisian actors and one actor of Arab heritage based in the UK. Chris White, who directed the premiere at the Arcola, co-directs this truly collaborative re-imaging with Ghazi Zaghbani, who also translated the play.”

This new production is called Trouf: Scenes from 75* Years. “Trouf,” explains Hannah, “means fragments in Tunisian but has a double, darker, meaning that it is something broken that cannot be put back together again … It feels even more poignant that this play of life under occupation it is being produced at Shubbak in this the 75th anniversary of the ongoing Palestinian Nakba.”

The land of Palestine is famously associated with olives, which as theatre maker Elias Matar says, can be bitter or sweet, like stories. He’s been leading storytelling workshops with members from the West London Arab community (from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Algeria) for almost a year and together they have devised Olive Jar from personal stories. “Olive Jar is not just a show, it’s an invitation to be part of something truly special,” Elias explains. “It’s a chance to come together, connect with new friends, and be inspired to open your own jars and share your stories.” Every rehearsal ends with a meal, where all participants stand around the table feeding each other falafel or foul mudammas and criticize each other’s recipes. The show will take place at Grand Junction, in a stunning Grade 1 listed Victorian Church.

From the Daughter of a Dictator, written and performed by Yasmeen Audisho Ghrawi, raises the question what if living in a democracy is becoming no different than living in a dictatorship? The play charts Yasmeen’s personal journey from Baghdad to Britain, via Beirut and Berlin. Armed with a degree in political science, international relations and anthropology, Yasmeen set about immersing herself in the world of human rights organizations but soon realized that a better use of her talents was to present her ideas in the form of comedy. She retrained as a physical performer and did stand-up alongside the likes of Jessica Fostekew and Nish Kumar. Her play From the Daughter of a Dictator was initially presented as a work-in-progress at Arcola Theatre’s Today I’m Wiser festival back in 2021 and now will have its premiere at the Lowry in Salford and Theatre Technis in London.

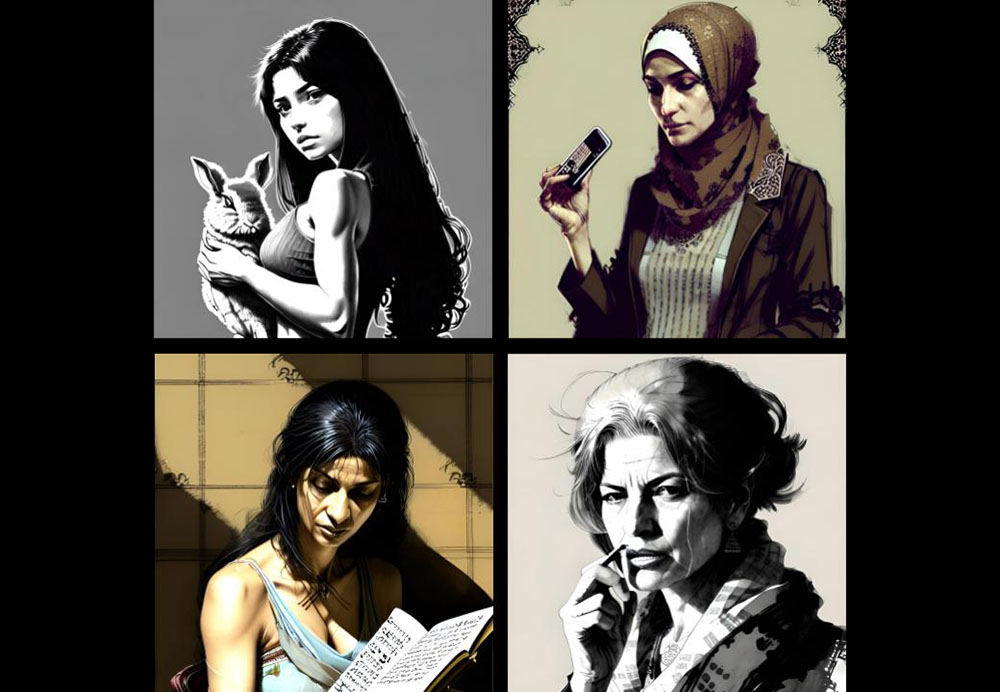

As a fan of short stories, which were my route to playwriting, I believe the condensed form is ideally suited to theater. In my new play, Chambers of the Heart, which will have a staged reading at the festival, I present four short stories of women from various parts of the Arab world as they confront love, desire and memory. These women straddle two worlds (or more) and have to forge their identities in the tension such positioning creates. The play is performed by Laila Alj who is Moroccan, French and British and directed by Sepy Baghaei who grew up in Australia and is of Iranian heritage.

Act 3: Comedy, Acrobatics and the Future of Theatre

From the Daughter of a Dictator and Chambers of the Heart have comic touches but if you are a comedy junky and crave pure standup then there are some excellent acts on offer in this year’s festival. They include All Hell Broke Loose performed by Shaden Fakih, the Arab world’s first openly queer comedian, whose standup is as daring as it is hilarious. Describing actresses in romantic movies: “When they come, they look angelic. Me, I look like the Exorcism of Emily Rose.” Her self-deprecating humor and sharp observations about the cultural differences between East and West will win her new fans in the UK. The show will be performed in Arabic with no subtitles. Double Bill: No Cheri / Mia Chara is performed by Palestinian comedians Sharihan Hadweh (in Arabic with English subtitles) and Manal Awad (in English). Sharihan’s No Cheri has taken the West Bank by a storm. As a blind artist she mines the absurdity of getting around in Palestine with its pothole-filled roads and busy pavements. The show is co-written with Manal Awad who will be performing Mia Chara in the same double bill. Manal is a well-known actress whose latest film Huda’s Salon (2021) was directed by Academy Award nominee Hany Abu-Assad.

Taroo

Growing up in Casablanca, Said Mouhssine was always drawn to extreme sports and doing acrobatics on the beach as many young people do. However, when he was shown videos of parkour, he was initially too afraid to have a go. Yet something about the sport fascinated him and he eventually overcame his fear and began to perform parkour stunts and even helped to create the first Moroccan Association for Parkour. Now Said brings his show Taroo to London, which combines circus, parkour, acrobatics, magic, and manipulation of one object, a wheely trash bin (called “Taroo” in colloquial Moroccan). The show celebrates, through stunts and comedy, those forgotten trashmen, often coming from immigrant backgrounds, who were on the frontline during Covid.

Finally, I will end on a show that blurs the lines between theatre and film. It is Pathogen of War by filmmaker Yasmin Fedda, offering an immersive experience about a mysterious pathogen born on the battlefields of war.

The rich variety of shows on offer gives the lie to the notion that Arabs are bereft of theatre. The idea that the world can be divided into societies with theatre and those without seems not only outdated but also to follow a very narrow definition of what constitutes theatre. What makes Arab theatre makers interesting is not that they are drawing on their own traditions only, which they do, but that they are having a lively dialogue with the world. This festival will not only speak to Arabs but to anyone concerned with the subjects tackled in the productions I’ve described. So come, see the shows, speak to the artists, get inspired, get engaged, become part of the event. That is theatre!