While the year 2022 marks the 60th anniversary of the end of the Algerian War and the country’s independence, at least three French museums and multiple galleries are celebrating the country’s history and Algerian artists this spring, among them the Institute du Monde Arabe (IMA) and the Institute of Islamic Cultures in Paris, as well as the Mucem in Marseille. Our reviewer saw the shows in Paris and Marseille.

Melissa Chemam

“Algeria my love – Artists of Algerian brotherhood, 1953-2021” at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris is surely one of the richest and most publicized exhibitions in the country. It opened on March 18, and will be visible through July 31, 2022. The works on view are from the IMA Museum’s Algerian collection of 600 works of modern and contemporary art, further enriched in 2018, 2019 and 2021 by donations from collectors Claude and France Lemand. Claude Lemand himself coordinated the exhibition with two other curators, Nathalie Bondil and Éric Delpont.

According to them, this exhibition is “a song of pain of the land and the Algerian people colonized and martyred.” For Claude Lemand in particular, it is “the song of culture and Algerian identity denied and uprooted. It is also the song of freedom and hope, the renewal of artistic and literary creativity and the announcement of a rebirth, necessary and long awaited. ‘Algeria my love’ is the expression of the love that all artists have for Algeria, the artists of the interior and even more those of the exterior, all these creators of the diaspora who can say, with Abdallah Benanteur: ‘Algeria is in me, only my feet have left; my spirit prowls permanently among my people.’”

The exhibition brings together 300 works of 18 artists, most active in the 20th century and some until today. Among them we find Baya Mahieddine, Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Kamel Yahiaoui, Rachid Koraïchi, Abdallah Benanteur, Abderrahmane Ould Mohand, or Halida Boughriet. “Algeria My Love” includes mainly paintings, but also some sculptures, drawings, books, photographs and videos. Most of the exhibited artists have lived mainly in Algeria; others have also lived in France, like Denis Martinez, born in Algeria in 1941 of French parents, and settled in France since 1994. The eldest is the non-figurative painter Louis Nallard, born in 1918, and the youngest, El Meya, is only 34 years old.

Of all the painters exhibited, few are known to the general French public, which makes the exhibition rich and unique. The most recognized is undoubtedly Baya Mahieddine, known simply as Baya, whose works are said to have influenced even Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

Born Fatma Haddad in 1931, orphaned by the age of five, she had to work as a servant in Algiers from early on. A completely self-taught artist, she painted landscapes, portraits, and floral and animal illustrations in flamboyant colors and shapes in her early teens, which quickly got her noticed. In 1943, the sculptor Jean Peyrissac showed her paintings to the French collector Aimé Maeght, who decided to organize her first exhibition in his Paris gallery, with a catalog prefaced by the surrealist poet André Breton. “I speak, not like so many others to lament an end but to promote a beginning and on this beginning Baya is queen,” he wrote. “The beginning of an age of emancipation and concord, in radical rupture with the previous one and of which one of the principal levers is for the man the systematic impregnation, always bigger, of the nature.” Baya was then only 16 years old. She met Georges Bracque and Picasso, before returning to Algeria where she married the musician El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine. The birth of their six children forced a pause in her career, but she resumed painting in the 1960s. Three of her paintings are included in the exhibition, in the center of the main room, radiating creativity.

Another woman artist is distinguished by the quality of works presented: Souhila Bel Bahar. Born in 1934 in Blida, in a family of embroiderers, she was first trained in sewing in Algiers, between 1949 and 1952, then became a self-taught artist. She began easel painting of the age of 17, inspired by works of Delacroix, Renoir, Corot and Picasso.

Other artists with international careers include the non-figurative painter and engraver Mohamed Khadda (1930-1991) and Abdallah Benanteur (1931-2017), steeped in Arab culture, connoisseur of European painting, also fed by the imagination of poets from around the world.

The photographs of Halida Boughriet, born in France in 1980, also stand out, offering portraits of Kabyle women matriarchs in family interiors very familiar to Algerians. And on the seventh floor one finds a monumental installation by Kamel Yahiaoui.

The whole of “Algeria My Love” forms an eclectic collection, and a beautiful historical presentation of the Algiers group of the 1930s, artists of the interwar and post-independence period, as well as some great contemporary names, even if the great Algerian names that have emerged in Europe since the 2000s — Djamel Tatah, Bruno Boudjelal, Zineb Sedira, Kader Attia, Adel Abdessemed, Mohamed Bourouissa or Neïl Beloufa — are conspicuously absent.

The ensemble highlights the trans-Mediterranean links of these artists, but their most political and anti-colonialist works are unfortunately not represented.

The exhibition is accompanied by a rich cycle of conferences and meetings, entitled “2022. Regards sur l’Algérie à l’IMA.” And the IMA also exhibits this spring the excellent work in Algeria of French photographer Raymond Depardon, pictures dating mainly from 1961 and 2019, in an exhibition made in collaboration with Algerian writer Karim Daoud, entitled “His Eye in My Hand.”

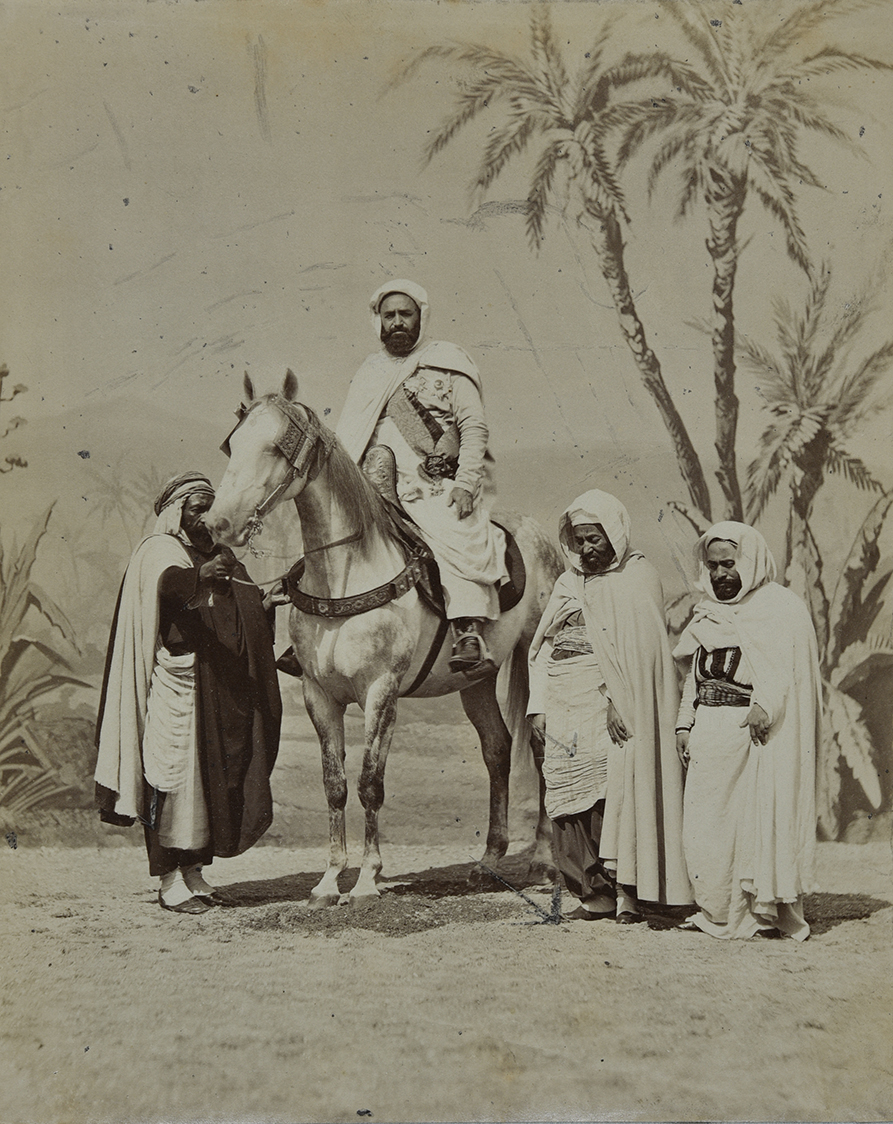

Meanwhile, in Marseille, the Museum of Civilization of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem) offers a unique exhibition with “Abd el-Kader” (from April 6 to August 22), dedicated to the hero of the Algerian anti-colonial resistance and the history of 130 years of colonization.

The exhibition, artistic but especially historical, traces the steps of the violent French conquest of Algeria, launched in 1830 by the July Monarchy, and which met at the time the opposition of the troops of Abd el-Kader until 1847, and this particularly through the paintings of Emile-Jean-Horace Vernet, known as Horace. The exhibition also shows how France betrayed its promise to free the Emir after his defeat, and to let him take refuge in the land of Islam, as well as the various controversies arising in France from these events.

Several texts and recordings relate the admiration of several French writers for the courage and honesty of the Emir, including Victor Hugo, who called him “the thoughtful, fierce and gentle Emir”; Arthur Rimbaud, who nicknamed him in a little-known poem “the grandson of Jugurtha”; and Gustave Flaubert, who wrote that the word “Emir” should be used “only when speaking of Abd el-Kader.”

Nearly 250 works and documents are brought together to put into context the greatness and growing popularity of the Emir throughout Europe, until his final departure for Syria. One finds documents from French and Mediterranean public and private collections, including the National Overseas Archives, the National Library of France, the National Archives, the Palace of Versailles, the Army Museum, the Orsay Museum, the Louvre Museum, the Aix-Marseille Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and La Piscine de Roubaix.

According to the curators, Camille Faucourt and Florence Hudowicz, “the Mucem has long demonstrated the desire to explore and expose the history of relations between the various shores of the Mediterranean, and this is obviously the case for what concerns the Maghreb and particularly Algeria,” such as Mucem’s earlier exhibition “Made in Algeria” (2016), or the cycle of meetings “Algeria-France, the Voice of Objects,” which has been held for the past five years.

The idea of this exhibition on the emir was born a few years ago, during a meeting between the Catholic father Christian Delorme, who had long harbored and interest in the figure of Abd el-Kader, and the president of the Mucem, Jean-François Chougnet. “They saw each other in Amboise, the place of captivity of the emir, in 2019,” explain the exhibition curators, and “the project was born at that time.”

The exhibition is timely for the people of Marseille, commemorating the anniversary of Algerian independence, and for history buffs.

From May 5 to 7, the Mucem also offered a program entitled “Algeria – France, the Voice of Objects,” with an outdoor concert of the group Acid Arab and Benzine, and meetings and discussions with the participation of authors, historians or Franco-Algerian personalities such as Benjamin Stora, Salem Brahimi, Lyes Salem, Ahmed Bouyerdene, Raphaëlle Branche, Christian Phéline, Faïza Guène, Magyd Cherfi, Slim, and Jacques Ferrandez.

With these two exhibitions, the IMA and Mucem devoted beautiful spaces to Algerian cultural history, in a special year, marked by lots of debate on France and Algeria’s shared past. These two French cultural institutions are of course expected to deal with this issue, as they specialize in the Arab world and the Mediterranean. Algerian artists have yet to conquer mainstream cultural spaces in France, such as the Louvre or the Musée d’Orsay, but these two events, dense and greatly produced, could well encourage a greater interest for Algeria’s artists across the country.