While TMR’s Arabic editor contemplates the unfinished titles biding their time on his bookshelf, he offers readers an assorted book list worth saving.

Mohammad Rabie

Over the past many years, I have cleaned my bookshelves several times. I got rid of the books I had read and knew I wouldn’t read again, as well as the books I hadn’t read and knew I was no longer interested in. In the end, what remained were the books I love and will return to, and others that I haven’t read yet. It is the latter that sit there, in judgment, filling me with an immense sense of guilt. These will chase me in the afterlife, just like left-over food.

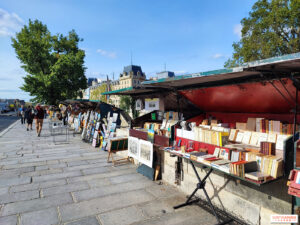

A visit to Cairo in the summer entails leisurely swathes of wasted time. Sweltering heat means I cannot work for long stretches, while the dryness caused by the onslaught of the air conditioner in the closed room makes me want to escape the oppressive conditions of my room’s confined space, and yet, even then, I cannot bear the humidity lying in wait for me outside of it.

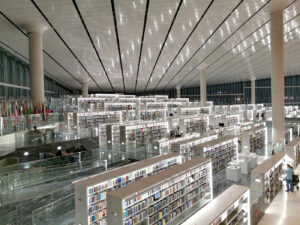

My library sits in the salon where there is no air conditioning, which means I cannot sit there. And so, in small bursts I stand in front of the bookcase allowing my eyes to run over each title, recalling everything: When I bought the book, where from, what drew me to it, and why I haven’t yet gotten around to reading it. I contemplate the shelves one more time before I make a complete turn around the room, as if disrupting the air will dislodge the heat and force it to subside, and then return to stand in front of the bookcase.

An entire platoon of ignored books will pursue me into the afterlife. Here are the names of a few of them:

Kitab al-Aghani by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani (The Book of Songs): I’ve managed to read five volumes out of a total of 24. Every Ramadan, for five years, I poured over one of the volumes. But after the fifth book, it appeared to me that all the stories resembled one another and I soon got tired of the books and the stories. I initially discovered The Book of Songs after I had completed reading an old edition of Shakhsiyyat Hayya min Alaghani (General Egyptian Book Organization, 1990) by Egyptian writer and novelist Muhammad al-Mansi Qandil (Living Figures in Song) which I found, surprisingly, far more graceful and sweeter than al-Isfahani. When I finally met Qandil and told him how much I had admired his book, he gave me a gracious smile, before furrowing his brows in jest as he recalled that it was the first book he’d ever published and that by bringing it up I’d unwittingly succeeded in reminding him of just how much he’d aged since then.

Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace: I cannot count the times I’ve sat down to read Wallace’s book until, ten pages in, I surrender in defeat at each and every attempt. There resides the colossal tomb on the third shelf. Its yellow-colored title embossed on a cover rendered with a blue sky with white clouds, beckons to me yet again. However, this is one that is just too cumbersome to finish and holds first place as the quickest novel I’ve ever given up on. Neighboring it on the same shelf is Consider the Lobster, a collection of essays by the same novelist. The ten pieces here tackle varied topics ranging from lobsters in Maine, the legitimacy of Ebonics as opposed to “white male” standard English, and John McCain, among others. None of the stories are connected and yet the author writes with great interest about each of them. Up until recently, I considered Wallace, who committed suicide in 2008, an enigma wherein I was baffled by why he wrote, unsure of what he was interested in given the diversity of his topics and their dispersion, both of which I have come to conclude were the secret ingredients to his success whereby he wrote to satisfy a raging anxiety about a multitude of subjects.

Concealed behind a few books I find Jim Elledge, the author of Henry Darger, Throwaway Boy: the tragic life of an outsider artist. This tells the real-life story of an artist and writer who found fame entirely posthumously. During his lifetime, Darger never once exhibited a single drawing or published a single word. After his death, hundreds of drawings and manuscripts were discovered, including a voluminous novel titled In the Realms of the Unreal. In his book, Elledge offers a detailed account of the man who grew up in a poor family subjected to various forms of ostracism, neglect, and abuse. Henry’s speculative writings, and his detached-from-reality sketches point to an existence lived in complete isolation whereby the artist surrendered to creating an alternate universe within his humble dwelling that fully compensated for the ugliness around him. I remember that I’d stopped reading when I was about a third of the way in. I found the details of Henry’s life exhausting – as would any reader I presume — and had only made it as far as I had buoyed by the passages excerpted from his novel, in which children triumphed over their oppressors.

Finally, my eyes rest on a book by my favorite American author, Kurt Vonnegut, who, I believe, has been much maligned by critics and academics, who’ve described him as prolific, teenager-centric, and banal. I’ve found Vonnegut’s A Man Without a Country to be razor-sharp and dazzling in which he writes with the thrill of a child on the cusp of adolescence. His uncomplicated, simple sentence structure and style deliver readers the experience of abject horror in Slaughterhouse 5, as well as utmost misery and satire in Slapstick, where my hand now finally settles. It is another that remains unfinished with the simple excuse that I had read everything else by the author up to that point. I contemplate Vonnegut’s ability to convey precisely what he wants to say in the fewest possible words, and it occurs to me to try to imitate him here as I re-construct the preceding sentence: He says what he wants using the fewest words.

This time, I’ll finish the book, and maybe I’ll meet Vonnegut personally in the afterlife.