In an apartment filled with memories of Che Guevara and Miriam Makeba, a once glamorous septuagenarian of Algerian independence contemplates the bitter end — earthquakes or worse yet, buyers of used furniture.

Salah Badis

Translated from the Arabic by Saliha Haddad

To Nicolás Medina Mora, Senior Editor at Nexosmexico

In Mexico City, many years ago, an itinerant peddler of used furniture recorded, to a tune, his daughter reciting the names of various furniture items one after the other. He mounted a loudspeaker on his car roof and played the recorded tape; thus he no longer needed to use his own voice all day long. After that, no merchants used their own voice. Copies of the tape spread, and all the old trucks trawling the streets of Mexico City carried loudspeakers broadcasting the voice of this little girl.

This lasted for decades. No one really knew whose voice it was, or what happened to the girl, where she was, whether or not she grew up and carried on her life in some remote town — or maybe in the same city, where she’d encounter her youthful voice several times a week as public property, a wandering ghost from the past reciting used furniture items now sunken in darkness and dust.

Whether or not the girl could be found, her voice became something of a tiny legend — a part of daily life of a city of 30 million people.

In another city 9,204 kilometers away, across an ocean, a city in which the air was still almost clean, a septuagenarian known to her neighbors as “Madame Djouzi” and among her friends as “Fadila” wakes up after sensing her bed moving, following a call similar to that of the little girl.

Ça bouge — it’s moving, she says to herself.

She opens her eyes, hoping it’s a passing earthquake, but hears screaming in the street. She closes her eyes again, and focuses. She hears the whistle of a distant train, and then the screaming again. She makes out the first word: Refrigeratooor … and realizes that it’s a used-furniture peddler: Refrigeratooor … sideboaaaaaard … stoooooove … usedfurnituuurrrrre.

She ignores the voice. She tries to sit up in her bed, and repeats: Merde.

Since her daughter and son left, Madame Djouzi prepares a pot of coffee before bedtime. She empties it into her red thermos, closes the cap tightly, and then walks with it to her bedroom. It is her way of avoiding morning daylight and street noise immediately upon awakening. She drinks one or two cups, pausing before engaging with the new day and its affairs.

Her daily concerns weren’t many, but they could still be tiring and difficult to resolve even when simple. Those concerns are always about her beauty salon, Nefertiti, which she’d been running for 30 years and which is a few steps from her house, near the Sacred Heart church.

“Bonjour, Madame,” says Assia, an employee of the salon, as she wipes the mirrors.

“Bonjour, Assia.”

Madame Djouzi heads straight to her small desk at the end of the salon, and puts her purse in the large drawer before quickly teasing her hair with her fingertips. She then moves towards the back of the salon and switches the light on, the stink preceding the view: the roof is leaking, a stain the size of an automobile tire that began as a small dot but metastasized rapidly.

She’s been trying to reach the first-floor tenant for a month. No one knows whom to contact; the turnover is high, and the apartments change hands every two years. In desperation, she called the police — her nephew is a police officer in Bouzaréah — and asked them to intervene. They said they’d come by today.

Madame Djouzi doesn’t favor extreme solutions, but she feels pushed to them now. No one listens to her; they all just shake their head, but don’t care about her collapsing ceiling and the stink, against which her employees spray perfume many times a day. All these residential buildings have maintenance issues: corroded water pipes, even sewage spilling into the streets and forming ponds. But no one cares, as though all the residents were just ghosts. Her friend Madame Lakhal told her it was because of earthquakes: they push the sea, which then washes under the buildings. The sea is slowly rising beneath the city, and one of these days it will devour it — that’s what Madame Lakhal said. Madame Djouzi sighs sadly as she sips her late-afternoon coffee.

She stands in front of her salon. Behind her, posters cover the old showcase, stuck between the glass and the dark curtain for years now, colors fading. The posters feature models wearing Eighties and Nineties fashions, so outdated they are coming back into style. The models pose in all seasons; some walk on snow, others on a beach in summertime, and still others, among exaggerated piles of dead red and yellow leaves, which now just resemble soil. Madame Djouzi raises her head towards the first-floor balcony.

Before midday, at around eleven o’clock, the police show up with a warrant. They park their car in front of the church and head towards the building, where they find Madame Djouzi standing.

She extends her hand to the lead policeman, who hesitates for a moment before shaking it. She wants to ask after Farid, but swallows her words instead and guides the officers upstairs to the apartment. The building, with its broken lamps, is calm; like every other old building, it exudes a wintry coldness. Madame Djouzi steps back and allows one of the policemen to advance towards the door. He knocks twice and asks, with a theatrical manner, whether or not there is anyone inside. This goes on for two minutes, which he counts on his wristwatch. Then he takes out a small toolkit and unlocks the door in three minutes.

Madame Djouzi opened her beauty salon at the beginning of the Eighties. Her two children had started school, and she had more free time. She hadn’t worked since leaving her job as a flight attendant after marrying Karim, the head of the international section of the French edition of El Moudjahid newspaper during the Sixties and Seventies.

During that period, Madame Djouzi still traveled, visiting various countries with her husband as he accompanied Algerian envoys to international conferences and summits in Asia, Africa, and South America. She keeps photos from that time in four big albums, along with dozens of objets d’art, souvenirs, and furniture from the places they visited.

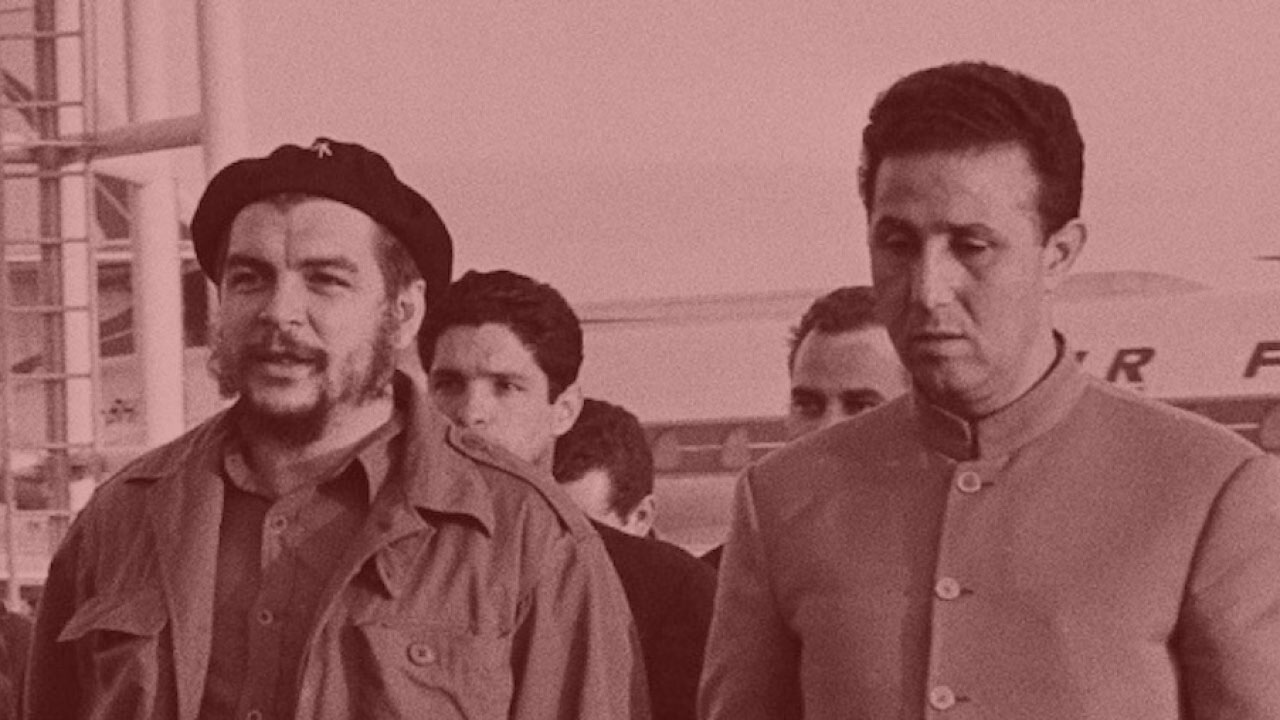

The photos, objects, and memories are all that remain from those years, but they make up the family history. Karim was secure in his position; he became the first Algerian reporter to meet Che Guevara, and had a three-page interview with him published in El Moudjahid in 1963. His framed photo with Che is still in place at the entrance of the apartment, where nothing other than the May 2003 earthquake had ever moved it: it fell, the glass shattering.

Madame Djouzi had pulled out the glass fragments, careful not to touch the photo. It depicted her late husband sitting on the edge of a chair, his back hunched to look into the camera. He’d put his large black recording device on a low table, which separated him and the relaxed Che, who crossed his legs and looked into the camera, too, holding a cigar.

In the days of panic that followed the earthquake and its aftershocks, Madame Djouzi went out with the photo, and took a taxi to Saïd’s shop in Mogador Street behind the Museum of Modern Art, where photo-and portrait-framing artisans worked.

Saïd — who framed all the Djouzis’ family photos and portraits — offered her a chair to sit as he worked on the new frame. He held the photo between his hands and looked at it for a few moments. He talked about her late husband and the glorious past of “great men,” as he called them; then he pointed to a large photo of Houari Boumédiène hanging high up, so near the ceiling that darkness devoured its upper half, and said: “May God have mercy on men …”

“… And women,” Madame Djouzi added. “Men and women, Saïd.” She watched him quietly as he placed the photo in its new frame and cleaned the glass with a blue liquid before holding it up and saying: “I remember that day like today, when Monsieur Karim, peace upon him, brought it.”

That was the second and last time Saïd would make a frame for the same photo, forty years apart.

The Djouzis had also hosted Miriam Makeba when she came to sing “I Am Free in Algeria,” as well as many other singers — Algerian and foreign — as well as journalists and writers with whom Karim liked to hang out whenever they visited the country.

Because of all this activity, Fadila couldn’t work; she remained beside Karim, taking care of the children and managing family life, making all the decisions from food to furniture to their clothes.

Visitors to the apartment in Debussy Street were usually astonished by the rows of objets d’art, books, and photos in the living room. Everyone who’d stepped inside it left a trace — a photograph or a souvenir or a signature in a book. The bookcase still holds a signed copy of a tome by the intellectual and diplomat Mostefa Lacheraf, as well as a copy of a poetry anthology by Jean Sénac. Madame Djouzi smiles whenever she remembers Sénac’s accent. Everyone was making fun of him one night, and joking about his high, pink socks. Karim took a photo of him then, but she doesn’t remember where it is. It might be in one of the albums.

After many years, the number of visitors dropped, as did the trips abroad, and Madame Djouzi started thinking about opening the beauty salon. She had had the idea after the last trip she’d made with Karim, to Mexico City, where they visited Lacheraf, who was Algeria’s ambassador there. Madame Djouzi always said that this trip was the most beautiful, the most memorable.

They visited sites of interest around Mexico City, and went to museums, guided by Lacheraf, who was studying the Aztecs at the time. Madame Djouzi toured castles in the suburbs, built near the volcanoes surrounding the city. She visited old, elite apartments in the city center, enjoyed unforgettable dishes, and discovered that Mexicans put sauce on their food just like Algerians. Mexican cuisine enchanted her, and she bought many cookbooks recommended by the women who had hosted her.

One quiet morning, from her Mexico City balcony lined with aromatic plants and flowers, she heard the voice of the little girl coming from a passing loudspeaker. She stood, trying to see where it was coming from, and saw a small, dilapidated truck overloaded with used furniture. Items were strapped to it all around with ropes, like a Gypsy family wagon. The loudspeaker released the girl’s voice — a strange, incomprehensible song. When she went back inside the apartment, she found that the table Karim had positioned near the bed the previous night had moved a few centimeters towards the window.

Some of the women working in the embassy had told her the story of the girl’s voice, but she didn’t say anything about the table that had moved; she thought that, as the city was surrounded by volcanoes, it might also be earthquake-prone.

Before going back to Algeria, she’d already made up her mind about the beauty salon as the best way to pass time and pull herself out of her isolation.

They discover a small puddle extending from the bathroom to one of the bedrooms. The pipes are in terrible condition, they say, and the problem isn’t only in that apartment: because it’s on the first floor, it absorbs all the leakages from the upper floors.

The police retreat, and the maintenance workers Madame Djouzi called start working. The furniture in the apartment is stacked: old, large, solid pieces and new, plastic, less valuable pieces. Every room is like an old basement containing shapeless heaps, half-hidden under worn-out blankets — and dust; dust coats everything, is under everything. Dust covers the entire apartment.

The workers must move some of the furniture outside to make some space, especially the furniture that blocks entry to the damaged bedroom. They carry it downstairs to the entrance of the building, but it hinders the movement of anyone coming or going; so they carry it to the sidewalk in front of Madame Djouzi’s salon.

Madame Djouzi looks at the furniture, at the deep scratches in the wood of the shiny, sharp-angled chest of drawers, the curve barely visible on the surface of a chair. But the maintenance workers also carry out other things: an old ENIEM-brand electric ventilator, a small, metal table, and some cardboard boxes secured with packing tape. They pile everything up in a parking space beside the sidewalk, and return to work.

The policemen are talking to two of the building’s residents. One of them was heading out but is surprised to see the door of the apartment open, with policemen supervising the removal of the furniture. The second one is coming back with his daughter from school. A policeman takes them to the entrance of the building, in the shade, and asks them some questions. He takes down their personal information and asks them to call the station or inform Madame Djouzi if they manage to get in touch with the tenant.

“There are too many people listed for this building,” one policeman says, wiping sweat from his forehead. “We still don’t know how to reach them; one lives in Annaba, and the other, in France.”

Madame Djouzi enters her salon. It’s nearly midday. Usually she leaves at this time, or a bit earlier if she needs to buy something from the souk. But she decides to wait. The workers might be done for the day, but still have to fix her damaged roof. And who will pay? She will, of course. They buy apartments and then abandon them.

There is one client in the salon. Madame Djouzi sits on one of the waiting chairs and arranges the magazines on the low table. She looks into the wall-length mirror and her eyes meet those of the client. They both smile.

When the police depart and the neighbors disperse, she sees, reflected in the showcase, a young man approaching the pile of furniture on the sidewalk. He is wearing a blue smock and steps cautiously, circling the furniture and examining it, but when he stretches his hand to sweep the dust off the chest of drawers, Madame Djouzi comes out.

“Good morning, Madame.”

“Morning.”

“Are these for sale?”

Madame Djouzi hesitates. “No, no. Need something?” she says in a shaky Arabic.

“No, just looking,” the young man replies, and smiles, exposing white teeth. He puts his hand on a wooden surface and knocks twice. Then he looks towards the salon showcase and says, “Beautiful salon …”

“Thank you,” Madame Djouzi answers in a choked voice, then knocks on the wooden surface herself. “Are you a merchant of used furniture?”

“Yes.”

“Were you the one who came about and yelled this morning in Debussy?”

“Where’s this ‘Debussy,’ Madame?”

Madame Djouzi hesitates to show her annoyance. She restrains herself, then answers, gesturing to her right, “Down here.”

“No, no, not me … but even I have been here since morning, and still bought nothing; do you have something to sell, Madame?”

“No … no. I don’t.”

Many of Madame Djouzi’s friends who live in old apartments in Algiers are convinced that such merchants head for their streets intentionally, because they know there will be rare items of furniture in the apartments there — furniture dating back to the Forties or earlier. When the Europeans fled in the early Sixties, they left a lot of that stuff behind. The merchants roam the streets in their blue smocks and ask after the furniture settling in darkness, moving it with their loud calls, which cause chaos in the apartments and which might prove dangerous when tall, heavy bookcases stir. Some people want to ban the peddlers, while others just seal the windows tightly and fasten their furniture so it doesn’t move. But Madame Djouzi doesn’t believe these stories.

“Right, and who owns these?”

“The neighbor here.” Madame Djouzi points to the first floor.

“Does he sell?” the young man says, smiling.

“You’ll have to ask him … if he comes …” Madame Djouzi murmurs.

“How’s that?”

“Nothing … nothing.”

The young man shakes his head and smiles again, then turns to go; but Madame Djouzi stops him. “Tell me,” she says, hesitating before asking: “What do you say when you’re yelling?”

The young man laughs, and scratches his head: “‘Refrigerator … sideboard … stove … chest of drawers … table … armchair … used furniture.’ But everyone says it in their way, and some add more pieces …”

“Hm,” Madame Djouzi says, then adds: “Thanks.”

“I’ll leave you my number, Madame; maybe you’d like to sell something?”

“Leave your number,” Madame Djouzi says, faking irritation.

“Give me a piece of paper to write it down, or save it on your phone.”

Madame Djouzi says, almost mockingly, “You don’t have a business card.”

“No, no, Madame … it’s not yet time for that.”

She hands him her phone; he enters his number, reads it back silently to be sure, then hands it back to her: “Write Walid, Madame. Well, stay safe.”

Madame Djouzi stands at the threshold of the pharmacy opposite the entry into Debussy Street, carrying a small bottle of pills — as usual, Amlor 5 mg. She tells the young woman how she’d felt that morning, but her blood pressure is unexpectedly steady thanks to the pills.

“Just take a break; maybe something’s been bothering you. Amlor 5 mg is fine … I don’t think you need 10 mg.”

She walks past the escalator that goes up from Debussy Street to Mohamed V Street. The temperature is moderate, but the humidity — as usual — is suffocating. Her steps are heavy.

The young woman had asked her if she takes her pills regularly, and Madame Djouzi said yes. She asked if something was bothering her, or preoccupying her lately. Madame Djouzi hesitated a bit, and then told her about her day and the problems with the building. The young woman listened attentively, then told her of a similar story that happened to the pharmacy some months earlier. Madame Djouzi had wanted to go on talking, to ask her if she had noticed something about the used-furniture peddlers, but the young woman interrupted her with a smile and went to help her colleagues with some clients.

At the door of the building, Madame Djouzi hesitates between the elevator and the stairs, then takes the elevator. She closes her eyes when the elevator jerks to a halt at the fourth floor. Catching her breath, she walks to her living room and sits on the first chair she stumbles upon.

She fetches a glass of water from the kitchen and sits in the large armchair next to the phone. She tells herself she will get her breath back, and then call Nouha, her daughter, who lives in Spain. She drinks some water and then looks up to make sure the furniture is still around her. She rises to open the curtains and let in the afternoon light, but still her living room remains dark. She switches on the large chandelier with its ten lamps, and looks at the furniture. To the objets d’art and the photos. She approaches the framed photo of Karim and Che Guevara hanging above the armchair, and brushes the men’s faces with the backs of her delicate fingers.

The dimness in the living rooms of these old buildings makes the furniture look ghostly, like dark specters or unidentifiable lumps of gelatin, not solid wood, marble, or brass that the feet of anyone crossing the living room in darkness could bump into.

She looks out of the window. The street is empty. The day is at its highest point, when silence reigns for a while, and temperatures rise. When Madame Djouzi is about to sit, the loud call reaches her again. She returns to the window, but doesn’t see anything. She hears the voice again.

She puts her hand on the cold surface of the marble table on which the phone rests, but doesn’t feel a thing. She sits in the armchair and takes out her cell phone from her purse. She hesitates for a moment: will she call from the land line, or the cell phone? Then she touches Nouha’s number. As she listens to the ring, she feels the armchair moving beneath her. She doesn’t panic. She doesn’t move. She doesn’t close her eyes. She continues holding the phone, waiting for her daughter’s voice, and stretches her other hand — without looking — to hold the framed photo of Karim and Che Guevara in place until the loud shout fades from the street. She will never let anything make the framed photo of Karim and Che Guevara fall again.