Hadani Ditmars

As I watch Afghanistan fall to the Taliban, in the flickering blue TV screen light of my living room in Vancouver, I’m reminded of another summer offensive. While many commentators have evoked memories of Saigon, it’s the fall of Mosul that springs to my mind.

It was seven years ago that ISIS invaded Mosul to no one’s great alarm, with Iraqi army forces seemingly dissolving into the ether against an opponent they outnumbered, just as 50,000 Taliban have overwhelmed 300,000 Afghan troops. In both cases, resistance to “insurgents” was mitigated by contempt for a corrupt regime. And in both cases, aerial bombardment by national armies — aided and abetted by Western allies — in attempts to root out insurgents resulted in untold suffering for captive civilian populations.

“Where there is ruin, there is hope for a treasure.”

But the game of spot the difference doesn’t stop there. In both instances it was and still is women and religious minorities who bear the brunt of both extremist violence and government corruption and ineptitude. And both Iraq and Afghanistan were once modern peaceful nations before decades of disastrous invasions, wars and foreign interventions made the sepia-toned images of 1970’s Kabul and Baghdad seem like far away dreams. The Taliban of course were largely a creation of the CIA and Pakistan’s ISI, with their jihadist textbooks printed in Nebraska; and ISIS was the monstrous love child of the 2003 invasion, foreign funding and an increasingly disenfranchised civilian population wracked by sectarian wars and rampant corruption.

Now, as thousands of civilian lives hang in the balance in Afghanistan and a sense of betrayal by the West haunts families hiding out in their basements, I am reminded that the only thing worse than being an enemy of the US is being a former ally. Just ask the ghosts of Saddam Hussein, the Shah of Iran or Manuel Noriega.

We’ve seen this movie before, and it always ends badly. As I watch the surreal images of Talibani in the presidential palace, and news of Prime Minister Ashraf Ghani abandoning his country, I feel a dizzying sense of freefall. Its velocity must be 1,000 times greater for my Afghan friends. The social media pleas of filmmakers like Sahraa Karimi to help save her country, followed by a video of her trying to save herself, evoke pure vertiginous terror as she runs through the streets of Kabul crying, “They are coming to kill us!”, sirens blaring in the distance and Talibani on tanks in the streets. She tweets later, “The sky of Kabul, which was silent in the evenings at night and the summer evening breeze forced you to open the window and leave your face in the cool breeze of living at home, is now full of the sound of helicopters, warplanes. This is the side of the shootings that breaks people’s hearts,” she added. “We are sold.”

In her breathless video, I notice, amidst her panic, her delicate features, and the red stone ring she wears on her right hand. As in Iraq, there is always room for beauty — and poetry — in the midst of horror. Sadly, in both places, it’s often the poets they come for first.

While I’ve been reporting from Iraq since 1997, I somehow never made it to Afghanistan. Iraq after all, was more than enough to keep me occupied — mentally and emotionally. And yet the fates of both nations seem interwoven, their people’s struggles often conflated, for better or worse. The pretext for the US invasion of both countries was to “root out terror” and both had their patrimony destroyed by foreign funded extremists. The Western outcry at the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan was universally condemned, while outrage about the destruction of Iraqi and indeed world heritage (not to mention the fate of Iraq’s people) in the wake of the 2003 invasion was underwhelming at best. It picked up again just in time for ISIS’ war on ancient sites, and their sale of antiquities on the black market to fund their “caliphate” — now in prominent collector’s living rooms in London and Geneva.

For my Iraqi friends, also watching the freefall and the terror from flickering screens in their own living rooms, this is déjà vu all over again. An Iraqi feminist friend in Baghdad posts on Facebook about the fate of Afghan women, using the image of the Afghan girl immortalized on a National Geographic cover in 1985, then a refugee in Pakistan after the Russian invasion, now perhaps to be a refugee again. She writes of the US withdrawal, “Why would the Americans regret their actions? They have done everything they planned to destroy and control the entire region one way or another.”

A Christian friend in the Nineveh Plain tells me he is having flashbacks about the night ISIS invaded his town of Qaraqosh in August of 2014, destroying churches in their wake. I am reminded of my recent interview with the Orthodox Archbishop of Mosul, who told me, “I can’t believe that the great powers — countries who have satellites everywhere — didn’t see ISIS when they came to Mosul. They stayed for two months, and no one did anything and then they came to our villages in the Nineveh Plain, and they let them do what they want. But when they tried to come to Erbil, they stopped them. When they killed al Baghdadi, they followed him by satellite, and they found him, and they killed him. That means when they want to do something, they can do it. But when they don’t want to, no one can push them to do it.”

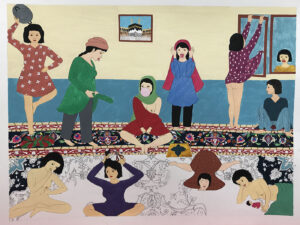

An Afghan feminist friend in Vancouver messages, “Don’t forget us in your prayers! A country that hasn’t seen peace for over 40 years. We deserve to be known for our culture, not our pain.”

Taliban surrounded Kabul, I were to bank to get some money, they closed and evacuated;

I still cannot believe this happened, who did happen.

Please pray for us, I am calling again:

Hey ppl of the this big world, please do not be silent , they are coming to kill us. pic.twitter.com/wIytLL3ZNu

— Sahraa Karimi/ صحرا كريمي (@sahraakarimi) August 15, 2021

Although I never went to Afghanistan, Afghanistan came to me. Canada, after all, has the second biggest North American diaspora after the US — at almost 100,000 — most of them refugees, including Maryam Monsef, our Minister for the Status of Women. As I went back and forth between my home in Vancouver, where almost 10,000 Afghans reside, and assignments in Baghdad, I fell into a relationship with Sohail, an Afghan-Pakistani-Canadian man, whose triply hyphenated identity spoke to the complexity of Afghanistan (a nation like Iraq), which in spite of its frequent stereotyping in the West as some kind of monolithic place, is home to many different ethnicities, faiths, cultures and languages. Both Iraq and Afghanistan boast cities that were once silk route crossroads, before the Great Game and cold war real politik, followed by disastrous invasions, occupations, extremisms and corruption, bled them dry.

Sohail’s mother, Aquila, was from an old Moghul family in Delhi, a cousin of the Sufi writer Idries Shah, and a descendant of Afghan nobility. His father was a Pashtun from the border area between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Long after the allure of her son wore off — I recall a breakup worthy of a Shah story, running out of petrol in his car in the middle of a bridge, just as he was lecturing me on some divine mandate that gave men dominion over women — my friendship with his mother remained strong. Aquila would take me to Afghan family parties and pass me off as a cousin. When I protested that I was Canadian — albeit with Syrian Christian ancestors — the relatives took me for an Afghan denying her identity. So eventually I just gave in and accepted my new “nationality” — much as I did in Iraq, where police would regularly try to stop me from returning to my hotel full of foreigners, not quite believing my Canadian passport. As I flew back and forth between Vancouver and Baghdad on assignment, I would return to Afghan-Canadian feasts of kabuli palau washed down by cardamom-spiked sweet chai.

Through Aquila, a Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Karachi, I learned about the stories of Mullah Nasruddin, recorded by Idries Shah in books like Tales of the Dervishes. I also learned about the formidable strength of Afghan women, as Aquila recounted how she was able to convince village head men in Peshawar to introduce birth control and modern gynecology for women there, in the 60’s. Where Western sociologists had failed, she won them over with her knowledge of tribal and Islamic culture as well as humor and even some Mullah Nasruddin stories. Aquila regaled me with tales of Kabul in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when it was an exotic tourist destination on the hippie trail and when Afghan Islam was more about Sufism than Wahhabist influenced, CIA backed terror. Rumi, after all, was born in Balkh.

I think of Aquila now, as her country faces fresh new terror, and of her Iraqi namesake, Aquila al-Hashimi, one of three Iraqi women in the post invasion Iraqi Governing Council, and the Sorbonne educated former French translator for Tariq Aziz. The Iraqi Aquila was assassinated in September of 2003 in the chaos of post invasion violence that made the streets unsafe for women, while I was there researching my first book on Iraq. When I first heard the news, I immediately thought of Aquila, the mother of my friend. As reports come in now of public executions in stadiums and door to door searches for those who worked for Western forces, what is in store for Afghan women, who like their Iraqi counterparts, have seen their hard won freedoms continually betrayed?

I remember meeting the Afghan Sufi singer Ustad Farida Mahwash at a Vancouver performance in 2003, shortly after the Iraqi invasion. Once a star of Radio Kabul, the “voice of Afghanistan” was forced to flee to Pakistan in 1991 when she was caught between two warring factions who both wanted her to sing for their cause, or face assassination. Now she lives in Fremont, California, a San Francisco suburb home to some 60,000 Afghans, known as “Little Kabul.”

I remember meeting Malalai Joya in Vancouver in 2010, the courageous Afghan parliamentarian who had the chutzpah to call the Afghan warlords installed by the US, well, a bunch of warlords. For this she was in constant fear for her life.

“Deals were made, it has been done,” a friend in Kabul writes me now, with a terrible finality. Americans certainly had no problem making deals with the same Taliban they invited to Texas in 1997, to discuss building a pipeline across Central Asia with the oil company, Unocal. Zalmay Khalilzad, who had served as a State Department official when Ronald Reagan was president and brokered the latest “peace deal” with the Taliban, worked as a consultant for the now-defunct company. In an op-ed for the Washington Post in 1996, he defended the Taliban, writing: “The Taliban does not practice the anti-U.S. style of fundamentalism practiced by Iran — it is closer to the Saudi model,” adding, “The group upholds a mix of traditional Pashtun values and an orthodox interpretation of Islam.”

Within a year, negotiations over the pipeline would collapse, when Al-Qaeda — offered safe harbor in Afghanistan by the Taliban — bombed two U.S. embassies in Africa. Now that same deal may again be in the offing, two decades, tens of thousands of lives and three trillion dollars later.

I consider the cost of things as I reach into my jewellery box and pull out an antique Afghan silver bracelet set with a garnet stone. It was given to me by Aquila and the red stone looks like the one in the ring Sahraa wears in her vertiginous video. I have kept it all these years as a kind of talisman for protection, wearing it even in Baghdad. In addition to its markets for opium, oil and weapons, Afghanistan is rich in gemstones, like emeralds from the Panjshir Valley, and rubies from the Sorobi region, between Jalalabad and Kabul.

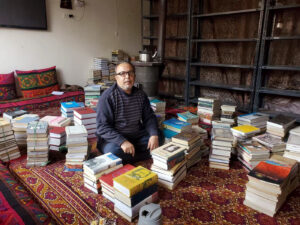

I gaze at an old Iraqi tourist guide from the ‘70s I picked up on Mutannabi Street, now commanding a special place on my desk. It opens with an image of Caliph al Mansour’s round city, and the title, Baghdad, City of Peace. My eyes turn to the flickering computer screen, and a popular image of women at a Kabul university in 1972, smiling and laughing, books in hand, dressed in mini-skirts.

I remember that, long before Afghanistan was a haven for warlords and extremists, it was the centre of silk road trade. I learn that, “Even before that, around 2500 BC, lapis lazuli was exported from Afghanistan to Iraq for the harps buried with the kings of the ancient city of Ur, some of which can now be seen in the British Museum.”

Growing tired of the televisual nightmare unfolding on my screens, my eyes turn to the dog-eared copy Aquila gave me of Shah’s Caravan of Dreams. I turn to a page with a story called Whose Beard?

“Nasruddin dreamt that he had Satan’s beard in his hand. Tugging the hair he cried: “The pain you feel is nothing compared to that which you inflict on the mortals you lead astray.” And he gave the beard such a tug that he woke up yelling in agony. Only then did he realise that the beard he held in his hand was his own.”

It seems a fitting one for Afghanistan.

And then I remember a poem by the Iraqi communist poet and Sufi-influenced Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati, whose politics made him flee Saddam Hussein’s early ‘70s CIA-backed purge (“My relations with Iraqi governments were never conciliatory. I belong to the Iraqi people,” he said) — a poem that would be equally at home in Baghdad or Kabul.

The Conversation of a Stone

A stone said to another:

I am not happy in this naked fence

My place is in the palace of the sultan.

The other said:

You are sentenced to death

Whether you are here or in the sultan’s palace

Tomorrow this palace will be destroyed

As well as this fence

By an order from the sultan’s men

To repeat their game from the beginning

And to exchange their masks.