Jordan Elgrably

Out of historic Palestine, stretching from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, Israel has created borders and ruins, a veritable palimpsest of a rich land, home to a diverse population, including Muslims, Christians and Jews. But for those whose fathers and mothers and grandfathers and grandmothers were born in the region, many going back generations, whether the map calls it Israel today, or Palestine Area A, B or C, for most Palestinians, only the nomenclature has changed, even as Israel has imposed an increasingly dystopic reality of unequal citizenship, or apartheid on the ground.

Certainly Israel’s Nation State basic law, or Nationality Bill, passed in 2018, imposes second class citizenship on its Palestinian population. As B’Tselem has noted, “It establishes that distinguishing Jews in Israel (and throughout the world) from non-Jews is fundamental and legitimate. Based on this distinction, the law permits institutionalized discrimination in favor of Jews in settlement, housing, land development, citizenship, language and culture.”

Palestinian Israeli filmmakers and performers benefit from Israeli nationality on one hand, when working and traveling in the west, but on the other, are criticized by Arab government officials for holding on to their Israeli nationality, without which they could not readily return to Haifa, Nazareth, west Jerusalem — or any number of small towns and villages, where they go to spend time with family.

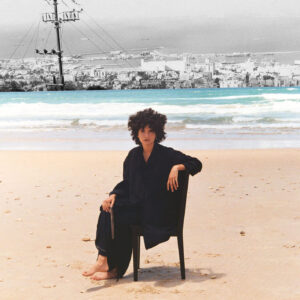

I connected with Palestinian actress and filmmaker Ula Tabari by phone in Paris, where she has lived for the past 24 years. A critic of the Israeli establishment, Ula made it clear that for her, there was no difference between the Palestinians of her hometown, Nazareth, and those in Bethlehem, Jenin or Ramallah; but when asked, she avowed that she would never give up her Israeli citizenship. This is her passport to her past, and the present.

Other Palestinian filmmakers who have chosen to live abroad, and are often dual nationals, include directors Michel Khleifi (Wedding in Galilee; Zindeeq) in Belgium; Hany Abu-Assad (Paradise Now; Omar; Huda’s Salon) in the Netherlands; Elia Suleiman (Chronicle of a Disappearance; Divine Intervention) in Paris; Sameh Zoabi (Man Without a Cell Phone; Tel Aviv on Fire) in New York; and Scandar Copti (Ajami) in Abu Dhabi, as well as the actress Hiam Abbass, who lives in Paris and directed Inheritance and Jerusalem, I Love You.

When I last spoke to Hany Abu-Assad, who thus-far has had one of the most successful directing careers a Palestinian could hope for — including two Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film — he seemed to have learned a great deal about himself and Israel, with years of hindsight. While he spends far more time abroad than back home in Nazareth, Abu-Assad also is not about to relinquish his Israeli passport. Do Israelis claim him, the way they do Arab artists like Anton Shammas or Sayed Kashua — both of whom have worked in Hebrew?

If you want to know if somebody is intelligent and has integrity, and also is a brave politician, man or woman, a brave artist, you ask him for his opinion about Palestine. —Hany Abu-Assad

“Israel is not one person,” he says. “There are open-minded people who are very supportive, and there are other people who find the idea that a Palestinian has made a good movie threatening. These people came to the conclusion the best way is just to ignore me, for the more they try to fight me, the more attention I’ll get. And they’re right, it’s the best way indeed.”

When I bring up the subject of Palestinians with Israeli nationality, and the matter of Israel’s apartheid for most Palestinians on either side of the Green Line, Abu-Assad seems a tad bored. “My honest opinion? I think Israel is passé. It’s like it’s past its expiration date. Behind our back it’s kept in the refrigerator.

“…It’s passé. As for the international call for Palestinian rights, for justice, this is bigger than Israel. What’s happening in general is that the United States is losing its place in the world, and this is going to have a much bigger impact on the world than the State of Israel…There are a lot of internal problems — just the idea that somebody like Trump was the president for four years tells you that it’s passé. So this is much bigger news than the State of Israel…With the United States, because it’s so big, nobody sees the downfall [coming], but it’s coming down and this is having much more of an impact than the struggle between the State of Israel and Palestine…We are almost on the verge of collapse, all humans. Let’s say another five or ten years? It’s going to collapse, the environment. Economically it’s going to collapse. You have an economy built on greed. Can you imagine? Which genius expects that this economy is sustainable?”

Although almost every one of the eight feature films Abu-Assad has made deals with Palestinians and Israel, today the director insists, “Israel and Palestine are irrelevant.” Nonetheless, he says, “I am using Palestine as a metaphor for, let’s say, human experience…Palestine for me is the weathervane, the compass, this is how I see Palestine now. If you want to know if somebody is intelligent and has integrity, and also is a brave politician, man or woman, a brave artist, you ask him for his opinion about Palestine.”

Michel Khelifi’s films, including Wedding in Galilee, inspired Hany Abu-Assad to evolve from his career as an aerospace engineer in Holland into a filmmaker known around the world. Khelifi left Nazareth — the largest Palestinian city in Israel — in his 20s to study theatre and cinema in Belgium. Khelifi has always identified as a Palestinian, but also as a citizen of the world, and he has spent more years abroad than home in Palestine. “I am the sum of my many parts,” he says. His movies are critical of Israel’s unjust policies against Palestinians on both sides of the 1948 dividing line. At the same time, they essentially form a cinema of liberation, which also takes a critical look at Arab society while promoting personal freedom, particularly women’s rights.

Hiam Abbass, about whom I’ve written elsewhere, synthesizes for many filmgoers the essence of Palestine. An international film star, she is a polyglot in Arabic, Hebrew, English and French. “In my youth,” Abbass once explained, “languages served as an escape route. I dreamed in English of stories without soldiers and oppressed women.” Raised in a village in the Galilee by liberal parents, Abbass remembers learning about tolerance from reading Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet. “Without it,” she says, “I wouldn’t have known how to love or forgive.”

As an adolescent during the 1973 war, Abbass continue to ask herself questions of identity, as a Palestinian on the west side of the dividing line. She has previously said that, “As a teenager, I imagined taking up arms. But that was not my path. I kept asking myself the question of belonging. I lived among the Israelis, I studied with them, but whenever a political problem arose, I was made to feel that I had a part in it.”

In her first feature film as a director, Inheritance (2012), which she co-wrote, Abbass captured the Israel/Palestine of her youth. “Originally I had set it in 2006, during the Israeli-Lebanese conflict,” Abbass explained. “But in the end, I decided to treat it as a collective memory of my childhood.” Influenced by her love of Italian cinema, Inheritance contains the essence of Hiam Abbass the actress, the screenwriter, the director, the Palestinian with Israeli and French nationalities.

The caveat? “I’m not responsible for the burden of representing all Palestinians,” she says. “I have only one identity, film and performance. In film you can explore so much more than you can with reality.”

Hiam Abbass drove home the truth that she does not see herself as a Palestinian symbol when she stated in an interview with Allociné: “…I consider myself a performer and a human being, more than someone who belongs to one people or another.”

Of the few Palestinian Israeli filmmakers who have chosen to stay, we can speak of Suha Arraf (born in the Palestinian village of Melya, near the border with Lebanon), screenwriter of The Syrian Bride and Lemon Tree, and director of Villa Touma; director Ali Nassar (The Milky Way; In the 9th Month); director Maysaloun Hamoud (In Between); actor Ali Suleiman; and of course, the greatest Palestinian Israeli actor of his generation, Mohammed Bakri, whose documentary as a director, Jenin, Jenin was banned in Israel last year after a protracted court case. Judges determined the film denigrated Israel for its role in the 2002 attack on the Jenin refugee camp.

Arraf’s film Villa Touma caused an uproar in Israel when it was released in 2014, because she called it “a Palestinian film” even though much of its funding resulted from Israel state institutions. Arraf responded with a stinging rebuke in Haaretz: “I am an Arab, a Palestinian and a citizen of the State of Israel,” she wrote in an op-ed. “The State of Israel never accepted us as citizens with equal rights. From the day the state was established, we were marked as the enemy and treated with racial discrimination in all areas of life. Why, then, am I expected to represent Israel with pride?”

When director Ali Nassar was asked about the issue of Israel demanding loyalty from its Palestinian filmmakers who receive government subsidies, he responded: “What’s a ‘Palestinian movie’? There aren’t any movies made with Palestinian money, because there is no Palestinian film foundation. So a Palestinian movie is a Palestinian story about Palestinian culture, by a Palestinian filmmaker, regardless of where the financial support comes from.”

While some Palestinian Israeli filmmakers continue to work in Israel, several no longer accept state funding, and of those filmmakers who have decamped abroad, few are willing to risk taking money from Israel these days.

Yet Palestinian filmmakers who are citizens of Israel are native Palestinians. They argue that they pay taxes, and have a right to expect full citizenship with equal rights, which includes access to state funding institutions. It is a terrible bind. As Ali Nassar told a Haaretz reporter, “The Israelis don’t want them and the Arabs accuse them, no matter what they do. In all the festivals I attended around the world, Arabs said to me, ‘Your movie is excellent, but why do you take money from an Israeli foundation?’ For years I was asked this, and answered that I’m not a collaborator, that I receive support from the film foundation because I pay taxes, I’m not doing them a favor, it’s my right to receive this money. I said to them — You don’t want me to take Israeli money? So let’s start a Palestinian film foundation with money from the Arab world and make movies. But I won’t forgo Israeli money because it is my full right, it’s my money.”

So many Palestinian filmmakers, performers and writers with Israeli passports now live abroad that some in Israel consider it a “talent drain.” Exactly what the future holds for Palestinian natives west of the dividing line is uncertain.