Two new histories of the Persian Gulf challenge often told narratives of the channeling of sudden petroleum wealth into visible, even spectacular, infrastructural development over the past 80 years.

The Center of the World: A Global History of the Persian Gulf from the Stone Age to the Present, by Allen James Fromherz

University of California Press 2024

ISBN 9780520398559

Making Space for the Gulf: Histories of regionalism and the Middle East, by Arang Keshavarzian

Stanford University Press 2024

ISBN 9781503633346

Several years ago, a UAE government — sponsored event highlighted how the country’s cities reveal a local history of religious tolerance. Among the speakers was a historian of the Persian Gulf, after whose talk the moderator posed a few perfunctory questions about the past. Setting up for his final question, the moderator sat up straighter and smiled: “What is your favorite place in the UAE?” The present tense seemed to catch the historian off guard, now expected to depart from the historical record toward what might seem like current-day messaging — the association being that religious tolerance begets great cities with favorite places.

After a pause, the historian responded along the lines of: “Well, I suppose I’d choose a place in the past … Dubai Creek … watching the ships come in, the cargo being unloaded from all over the world.” The answer referred to Dubai’s historical harbor — on water, not land — whose coordinates might persist but whose spirited ensemble of stevedores and crewmembers no longer does. That onstage unease with the present came to mind several times while reading two recent histories of the Persian Gulf.

In writing history, the authors of these books make express choices to address a present, specifically one largely dominated by a narrowly crafted narrative. That narrative often gets told as the channeling of sudden petroleum wealth into visible, even spectacular, infrastructural development over the past 80 years. History, in other words, arises out of the visible construction and urbanization of cities like Doha, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi, or in the failure of such plans to be realized, such as on Kish Island in Iran. Both of these writers want to release the Persian Gulf from that telling. To do this, they each suggest how history can offer different, maybe even liberating, ways to see these cities today. Results in both cases involve some awkwardness, perhaps validating the hesitation of the historian at the event but in no way undermining their own arduous work and the valor of the task they put before them.

In The Center of the World, Allen James Fromherz sets out to resituate the Persian Gulf by resetting its relationship with the rest of the world, namely by asserting that it is really important. Not in the way that geopolitical strategists have in the recent past — that is as the pumping heart of our petroleum-addicted societies, but rather, on the contrary, by conjuring up a deeper history. Fromherz collapses the region’s petroleum-extraction years into a few mentions in a book that claims to cover from the Stone Age to the present. The result, he seems to suggest, might help to suture “an artificial line … [that] like a surgeon’s wound, has split the belly of the Gulf in two, between Iran to the east and the Arab states to the west.” Each of his chapters is named after a port city, on one side or the other of that line, which characterizes and reigns during a historical era. As much as things have changed, Fromherz argues, historical approaches to trade and survival remain traceable in Gulf societies today.

In Making Space for the Gulf, Arang Keshavarzian focuses mostly on the era from which Fromherz turns away. For Keshavarzian, the way to address the problems of a reigning narrative is to problematize it, namely by scrutinizing it through a telling less constricted by chronology and more transparent about his own search for a history. He reminds the reader that geography is a kind of writing, on land itself. And therefore, like history, it is an act of construction. Rather than constructing an alternative narrative, he aims to reopen a “boundless regionalism.” His work can be regarded as a reverse engineering, to borrow the term from Robert Vitalis in his work on Saudi Arabia and American oilmen. Whereas Fromherz insists on a new narrative, Keshavarzian remains suspicious of any narrative. You could say, he just wants to free the Persian Gulf, to let it ebb and flow on its own terms.

Whether explicitly or not, both writers converse with recent themes in the writing of global history, which, most generally, prioritizes ideas and networks unconstrained by national borders. To work this way, they are indebted to histories composed across other waterbodies — the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean, for example. One back-cover blurb claims “Fromherz does for the Gulf what [the historian Fernand] Braudel did for the Mediterranean.” Keshavarzian refers to the Persian Gulf as an “arena,” a metaphor regularly applied in studies of the Indian Ocean. This legacy of history writing opens the door for the writers and their readers to see the Persian Gulf as a connecting point rather than a delimited void.

Moving through more fluid space and time, the books manifest also from voracious reading projects, a sign that it requires access to many minds to write global history. In ways too rarely explored in histories of the Persian Gulf, Fromherz revisits and brings to life medieval texts that remind us that rocky and marshy ports, like Sifar, existed and receded from view long before the settlements that took the spectacular shape of global capitalism today. This combined synthesis is a healthy dose of “timefulness” to the region. Keshavarzian refers to “a tsunami of knowledge production about the Gulf,” from which he deftly brings forward recent achievements and emphasizes some of the most salient parts. In both books, the strongest, most surprising moments occur when the writers source from texts rarely cited in English-language histories.

For close observers of the Persian Gulf, there can arise a bewilderment at the ease with which many experts and laypersons alike narrate the region with quick pronouncements. Early on, Keshavarzian notes that just by uttering the name “Persian Gulf,” one “can raise temperatures” in discussions online or in real life. Even people without lived experience in the region will make sweeping claims to it in one ideological way or another. It can be reason for a historian to remain reticent at certain times. This contentiousness today has more to do with the southern, Arab coastline trapped in a forever present, while the northern, mostly Iranian coastline is blanketed by the past. Both books suggest potential exit ramps from this echo chamber. One way to defuse flare-ups has been to spread history around, or more broadly, to assert that there is history throughout the Persian Gulf littoral. History permits context; with it, a writer can emphasize continuity or breakage. Fromherz opts for temporal continuity, while Keshavarzian chooses temporal breakage, even if he imagines geographical flow.

Geography as History

Geography and history might be faces of the same coin. (Pursued today as distinct fields, they may now be reuniting.) You can’t talk about time without talking about space. You can’t talk about space without accounting for how people and other forces have made it. To expand upon geography as a tool for rereading the Persian Gulf, Fromherz expands the spatial by identifying three distinct geological zones: mountains, marshes, and vast deserts, each with a role in determining fates of those who dare to navigate them. In between these zones, he identifies the Persian Gulf’s “very narrowness that creates a psychological sense of close encounters …, making it such a rich cauldron of interaction.” This Jared Diamond–like attention to geography operates, however, as a secondary theme in deference to his overarching objective to reach back in time at an epic-scale.

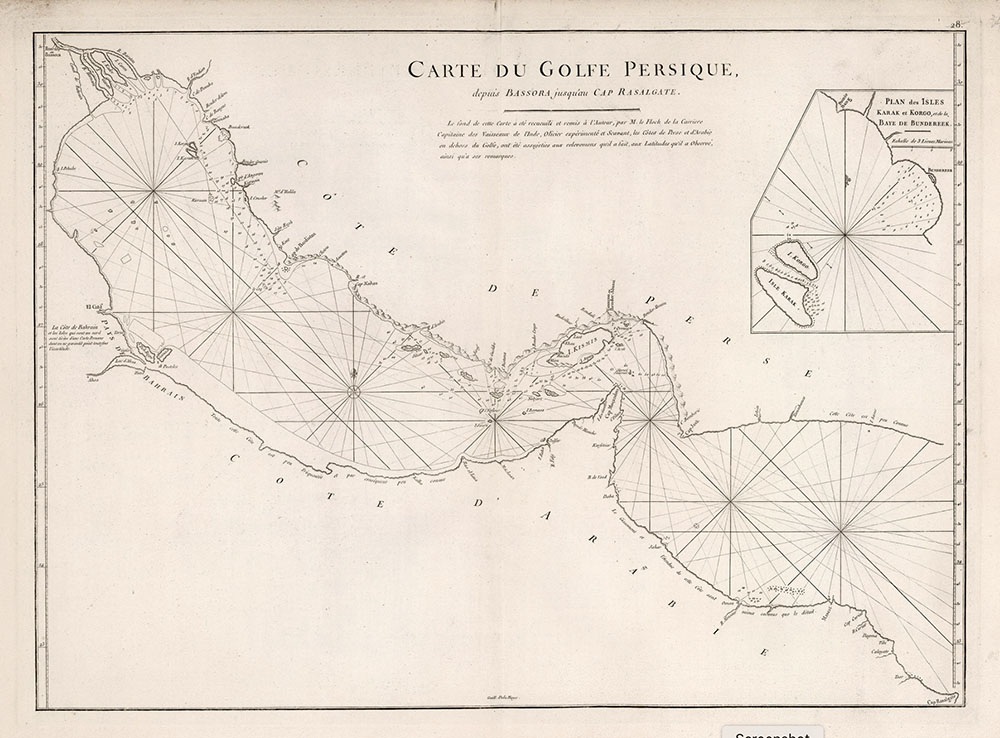

Keshavarzian is meanwhile preoccupied less with timespan than with how the Persian Gulf, as a body of water, gets spatialized. At the start of his book, he describes the Persian Gulf as three-dimensional movement — a basin of water that merges into marshlands to the northwest and compresses through the Strait of Hormuz to the east. He looks out at a “mutable, created space that does not exist as a passive stage but is assembled out of human actions.” Keshavarzian provides a date, January 4, 1980, not for when history begins but when “an earlier regionalism” was flattened into the abstraction of a US foreign policy. It was a moment when the Gulf’s two-dimensionality on a map fully overshadowed a three-dimensional reality. On that evening, already the next morning in the Persian Gulf, US president Jimmy Carter delivered what later came to be known as the Carter Doctrine. Sitting next to a globe positioned to alert viewers where on Earth he was talking about, the US president equated, and reduced, that part of the world to a US “vital interest.”

Keshavarzian calls this conversion an abstraction of the waterbody’s geography into a “unified territorial object ready to be enclosed and captured.” The result is not just some visualization shorthand. It is an abstraction of the Persian Gulf that idealizes a distinct, stable, and secure region; if it is not all of those things at once, then military intervention is required. One may argue that most inhabitants of the Gulf are unfamiliar with the Carter Doctrine, but Keshavarzian’s point is that this narrative of containment is pervasive enough to shape not only how the world perceives the region but also how lives are lived there.

Bullseye

You’ve most likely encountered advertisements that visualize the Persian Gulf as the bullseye of a target. The Persian Gulf is pinned as the mark inside concentric circles that radiate outward: to promote the service reach of a Gulf airlines; to tout globally relevant real estate investment in Dubai; or to pitch that Qatar, and now Saudi Arabia, will host millions of nearby fans for professional soccer. The website for Dubai’s airport authority describes the city’s “geocentric location,” a four-hour flight from one-third of the world’s population. The message is that Gulf cities adjoin a great deal of the world. Even if you suspect that the bullseye is terra nullius, it is in the very least girdled by the world’s densest assembly of humanity.

To illustrate Fromherz’s claim for the center, the book’s dustjacket references the bullseye, with the Persian Gulf coastline reverberating outward over the cover. Already with the book’s first sentence, however, centrality gets qualified: “The Persian Gulf is the center of world history.” So now the claim is merely historical, not, say, political or financial. From there onward, the text is peppered with chronological superlatives that might remind readers of other regional marketing campaigns that advertise the first, tallest, biggest, etc. On page seven, the Persian Gulf is “the world’s first global sea”; then on page eight it is a “liquid launchpad for so much of history.” At the start, the author confidently states that ports around the liquid offered “the world’s first and oldest example of globalizing space — and non-Imperial at that.”

Fromherz’s pre-global global world begins in Dilmun, in current-day Bahrain, where he claims “trade first emerged” as a waystation between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. It’s another untested factoid, but one that nevertheless captures the Gulf as an in-between. However, if one is compelled to identify a center, then there must also be a periphery. Fromherz attempts to avoid labeling the rest of the world periphery through a sleight of logic, namely that the Gulf is the center because its inhabitants always exploit its status as the fringe, or “the periphery of empires.”

Many of Fromherz’s assertions remain under-explained, but they nevertheless accompany an enthusiastic, even contrarian, survey of early activity on and around the Gulf. He even finds a morsel of contemporary Western moralism directed toward the region, in Paradise Lost no less, where John Milton remarks of the “sinful decadence” in Hormuz. It’s difficult to imagine 17th-century bling on today’s scorched and craggy Hormuz Island. While Milton’s censure seems inconceivable today, it highlights how fortune in the Persian Gulf has drifted like weather clouds from one port of call to the next. I read also with fascination of the rise and fall of bandars (Persian ports often hemmed in by moutains), of Basra’s geological drift away from the Gulf coast, and about just how dependent the Abbasids were on Persian Gulf trade.

Headed to Dubai

Whereas history has often been a domain for accounting the world’s modernization, global histories provide the opportunity to break through this limited lens. In this regard, I am sympathetic toward Fromherz’s goal to look for echoes and continuity through a longer past and to reinfuse a geography with histories beyond ones visually evident today. I closed the book with some questions about what we are to make of recurrences, especially as committed as Fromherz appears to be in placing them in current imaginaries about the region. Recurrence, however, often feels like permanency, as when he identifies a “Gulf model of distinctive cosmopolitanism and autonomous ports” that reaches to the 900 C.E.

That apparent model — he refers also to a Dubai model — spans “from ancient Dilmun on Bahrain through medieval Islamic Basra and Siraf to Muscat, Hormuz, and Dubai,” and has “created a globally connected Gulf culture dependent on the free flow of people, commerce and ideas.” Each of those port cities mentioned is a chapter title, with an apparent culmination in the final Dubai chapter, as if the city is the manifested vessel of history. History can be described as a lens through which one can observe the world as an accumulation of temporal processes, but is there an allowance here for sediments to erode and shift? Although global, or deep, histories strive for expansiveness, the results can be the opposite — compressing eras into a few hundred pages and leaving no room for absence, standstills and abandonments. Does tracing continuity necessarily lead us toward the always? Claims to continuity can start to vaporize into what could be a universalism. “Ultimately,” Fromherz writes early on, “human adaptation and adaptability have been the keys to long-term success in this region.” That also summarizes Darwinism.

In the Dubai chapter, Fromherz writes, “Gulf culture has always favored informal networks over formal institutions.” Such a statement runs the risk of being a banal truism or airbrushed history. This assertion in particular runs counter to how governance is experienced by most people in Gulf cities. Elsewhere in the book, he refers to someone else’s coined neologism — the so-called “Dubai Model” — which, for all its misrepresentations, does encapsulate the historical tendency toward more centralized, and therefore formalized, government. “Gulf society today,” Fromherz asserts, “still rests on long-term continuities such as informal institutions and practices that link citizens, foreigners, and rulers.” Of course, there are relational transactions and decentralized ways in which residents work together, but this can only happen after centralized processes have allowed the vast majority of them to be there in the first place.

Dubai’s professed formal institutions are also part of a seventy-year campaign to formalize governmental oversight — whether in monitoring hygiene at slaughterhouses and eateries in the 1950s or through assertive Covid measures in 2021. Regulation is part of what makes the city so appealing to the more fortunate newcomers: you know the rules and how to arrange things like residency papers and utilities. You pay published fees, not negotiated bribes. Formalized institutions exemplify state modernization programs which are based in colonial measures (which Fromherz often seems ready to play down), which consequently are based on histories of extraction, that age of history he’s chosen to demote.

Arguing for continuity can cascade into a tale of timelessness, into an essentialism that begins to emerge in such statements as, “Under the surface of hyperglobalization, the distinctiveness of Gulf communities and Gulf citizens remains.” Wilfred Thesiger wrote similar things before the there was a term like “hyperglobalization.” The mental image here is that of a layered being, outwardly open to perpetual openness with an innate closedness underneath. Fromherz conjures an identity that holds the two simultaneously and apart, with no admission that identity can be anything other than monumental and unchanging. Similar sentiment, for instance, can be found as themes permeating through heritage museums throughout the Gulf. And for all his claims to continuity, aren’t then the assertions of “firsts” in trade and globalizing space then suspect? In her book on early world systems, Janet Abu Lughod wrote, “Thus, if it is possible to argue that a world began in [one] century, it is equally plausible to argue that it existed much earlier.” Is Fromherz’s reach to the Stone Age merely to assert that he can identify the firsts because he encapsulates all history?

It’s hardly surprising that Fromherz’s chronicle of scruffy ports concludes with Dubai, a city he observes functions as a “byword” for other cities in the region. The chapter portrays the city as manifestation through a regional refinement of techniques and strategies. This would have made for a more rigorous argument if it had not seemed that Dubai’s leadership has it all figured out. There’s little room to consider ongoing and future change, much less the criticism and hardship that persist. At one point he recognizes Gulf cities’ dependency on “the labor and expertise of immigrants from the rest of the world.” He briefly mentions reports of exploitation and labor abuses. I realize a history is not required to focus on these matters. However, when the next paragraph couches them in “a long history of importing labor from abroad” without much more than that, I’m left to question why and how he frames these contentious topics. To see today’s issues arising from a deeper history than oil extractions — beyond even colonial networks — is a point to be made, but how does that shape a reading of unfair labor practices today? What does merely mentioning a “long history” afford us?

Between Iran and the Arab Gulf States

Keshavarzian’s argument does not lead to a concluding analysis of Dubai, but it relies on that city as that recurring byword for the region. He digests an abundance of recent work on contemporary Dubai, a performance which intelligently highlights aspects of that work. Still I wonder whether Keshavarzian could have provided some fresher perspective on the contemporary experience of the Gulf, for example from less documented vantage points looking toward Dubai. This might have revealed just how pervasive reigning narrative can be.

Some of Keshavarzian’s most interesting moments occur when he cites primary and secondary Iranian sources, rather than the great ocean of Western presses. For example, he corrects the historical record about the rise of the region’s largest port facilities at Dubai’s Port Jebel Ali, by expanding our understanding of the high-stakes maritime brinkmanship from which it rose, namely that the Iranian government had similar ambitions on Kish Island. This is an example of the intersections and correspondence between the Gulf’s northern and southern shores that Keshavarzian seeks to restore in telling of a regional history. The book includes an entertaining sidebar about Kish, often portrayed as a last-gasp attempt by Iran’s Pahlavi monarchy for global relevance. Keshavarzian’s entertaining biography of the island, oscillating between centrality and periphery, serves as a parable for just how malleable geography can be.

In recounting his own uneventful visit to Kish by boat, Keshavarzian observes his fellow travelers whose “time seemed to be controlled by someone or something else.” There’s a reference to how these people hiding in the shade take part in smuggling networks, or at least small-scale trade markets. Such markets on the Gulf’s northern shores kept southern ports running before oil profits were more secure. As Keshavarzian observes, they still operate today with a constant gargle of cigarettes and home furnishings that maintain connections between north and south coasts. I paused at Keshavarzian’s observation of these small players in the bigger game. Their movement is shaped by restriction, laced with boredom and fear. The writer’s keen observation made me curious to read more of his floating vantage point set at eye level.

There are hardship and risks in immigrating to today’s Doha and Dubai, and there must have been as well in medieval Sifar. These toils aren’t the focus in either book. Again, I don’t argue they have to be. But their absence does tell us something about reigning, state-supported narratives, and whether we might be able to live outside them. Cities become rich and relevant and eventually collapse into irrelevance, but the people in them remain largely unaccounted for. I realize that reading a history “from below” of 10th-century Sifar might not be able to bring much to light on this matter from available sources. Nevertheless, the risks of the migrant arise as collateral erasure when they disappear in written histories of cities.

Seeing for oneself

In histories that take on wider scopes, global networks and the planetary movement of people tend to flatten into arrows on a map. This tendency denies that migration has less to do with movement than the pursuit of finding a home. Fromherz observes a “long history” in the matter, but he does not assess the harm that these rather recent systems have inflicted on many people. These labor and migration patterns arise out of the aspects of history from which he wants to shift our focus. Keshavarzian refers to “new legal categories of natives and foreigners [that] had far-reaching ramifications for the circulatory labor migration that had long knitted together the Gulf littoral.” In other words, the very nation-making made the 20th-century migrant as we know her today.

So often the lived experience of migration is reduced to movement, overlooking the desire just to live somewhere or, worse, the drudgery of delay or the hiding in fear. In the last months, in the aftermath of Bashar Al Assad’s swift departure from Damascus, the Barsha neighborhood of Dubai has come to mind, where such liveliness is matched only in the streets around that old harbor Dubai Creek. Fifteen years ago, Al Barsha was quiet, not yet swept into the city’s building boom. Then came the Arab Spring and the city’s receipt of Syrian people and money. Today Al Barsha is known for Syrian restaurants and shops. There are also Korean, Bosnian, and Tunisian storefronts, and a Starbucks. Every night storefronts glow and fill up with customers. Who knows how many Syrians have found refuge in Al Barsha, filling the curtained apartments above. Below on the sidewalks, Syrians I know smile at the semblance to Damascus. Migration in this regard is settling for a notion of home that spans distances. Twice, Fromherz refers to precious wood being stripped from ships to build multi-story houses in port cities. One should note that the conversion was not the other way around.

Keshavarzian addresses movement not so much as the flesh of his plot but its skeletal structure, that is his own mobility, or immobility, whether it is physical or optical. In his attempt at opening the Persian Gulf to vaster interpretations, he pursues his “boundless regionalism” though without relinquishing to a geographical nihilism. There is a place, however much in formation, that can still be touched and lived. With precision and some confessed extemporization, he charts an artful approach to the Persian Gulf, one that foregrounds history writing as an act of contemplation and finding one’s bearings. The region is in movement because the humans who look at it are in movement. His perspective as a writer is one “that fluctuates over time, and depending on where one stands.” In this way, scales of distance, and of time, become relational and contingent. The writer’s standpoint can be both evident and multidirectional.

Though the Persian Gulf is neither center nor periphery for Keshavarzian, it is personal. Another recurring theme in global history is that its writers reveal how they relate to the topic and its geography. For Keshavarzian, the cities of the Gulf became a migration story at one point he could not enter. At the end of his book, it is his own mobility, or immobility, at play. He recounts a reported affair from 2017, when his application for a residency visa was denied for a work term at his employer-university’s satellite campus in Abu Dhabi. Fromherz recalls his “hands-off” fellowship enjoyed at the same university, but that description took on new meaning for Keshavarzian. For the latter, the rejection is a way of entering the present, a reminder that our vantage points confront blind spots and vanishing points, but the kinds that challenge or nullify reigning narratives, in his case dealing with the adjudicators of Western liberalism.

If writing history is an act of construction, then it can also be very much a part of a struggle, against the grain of narratives whose pervasiveness is hard to pin down. Keshavarzian both questions the existence of a particular region and examines it as if it does exist. His is a history that does not dabble in predeterminism. He calls for an “unmooring [of] our perspective,” not so that we take on a godlike aerial view but so that we acknowledge our own pivots, turns, and displacements. “I had to sit with the binary interpretations imposed by the powerful in Tehran, Abu Dhabi, Washington, and London but tried to insist on the multitude of histories and conceptions of space and belonging.” At a moment when his very presence and value at a university were being tested, he reveals he also saw a chance to “insist” on other realities he had witnessed.

Both writers assert that we all formulate a history we may not ourselves write down. In regard to Fromherz’s enriching accounts of Siraf, Dilmun, and other port cities nearly entirely sedimented into the earth today: if they don’t have to perform as the loci of an enduring, rough-hewn character, then might they contribute to how one looks out at the world, to how one sees water and land as witnesses in and characters of human-written history? A global history is among other things an acknowledgment of one’s place in the world — but not so much the coordinates that measure your distance from a pinpoint. Rather one’s vantage point is a stocktaking of whence one has come and to where one plans to go, in time and in space. The view before you shapes your response. A global history as a way of simply moving through the world, of engaging with other people, is a lesson not so much with an legible assertion but of a resilient cartography, for engaging a world redolent of buoyancy and cruelty. It offers a way to reconcile the fact that one’s vantage point is both essential and infinitesimal.