As the crossroads of Lebanon, Beirut has undergone myriad evolutions over the years, with multiple periods of urbanization, reconstruction and gentrification, a process which has often left by the wayside migrants and the poor, but as a result, everyone loses.

Ghida Ismail

On a sunny November day last year, a street vendor ran panickily down Beirut’s Corniche, pushing his cart, laden with corn and cotton candy, and crying out in agony. He was being chased by three police officers, who eventually caught and cuffed him. A little more than a year earlier, in June of 2021, a corn vendor had burned his food cart out of desperation and frustration in response to the police’s attempt to shut down his business on the same corniche.

Such scenes of the clearing out of street vendors have been unfolding on the streets of Beirut for decades, sometimes seen, most times not. The active eviction of street vendors represents visible symptoms of what the Lebanese sociologist Samir Khalaf has called the “culture of disappearance” in Beirut, where not only urban heritage but also routines of daily life and livelihoods are being effaced and discarded.

In search of street vendors in Beirut

In 1973, Khalaf wrote in his book Hamra of Beirut, that, “with all the proliferation of shopping and retail facilities, peddlers and street vendors continue to provide a rather colorful and expedient outlet for some daily items.” An article published in Annahar in February 2019 characterized pre-war Beirut as “bustling with life,” with street vendors carrying their products on their shoulders and heading to the old Bourj in the morning and then to schools in the afternoon. The article recounted all the various products creatively packaged and sold by vendors, including pickles, beetroot, corn, kaak, ful; it described the smells and sounds that accompanied the vendors in Beirut’s streets and enticed customers to them. Street vendors used imagination and ingenuity to maximize their economic gains and secure their livelihoods.

A few months ago, I took to the streets of Beirut in search of what remains of street vendors in the city, starting on Hamra Street. I did not find any. I asked two older men with permanent stalls on the sidewalk about the mobile street vendors. They confirmed that I would not find any on Hamra Street because they had stopped working there long ago. They explained that the municipality would come after the vendors, harassing them, confiscating their goods, and paralyzing their work. Both of them considered the erasure of street vendors from the neighborhood disappointing, mainly because they would sell vegetables and fruits at a more affordable cost. “They really fulfilled our needs,” one said (“Bi fesho el aleb,” in Arabic).

A few weeks later, I caught sight of a mobile vendor passing by on Hamra Street, selling corn. He was the first street vendor I had seen there, and I rushed to him to understand how he was able to work. He told me that the municipality usually does not allow them to sell on Hamra Street or nearby Bliss Street, where the American University of Beirut is located, unless they have political connections. He emphasized that there is demand for the items sold by vendors, and there is potential for such items to generate a sufficient income; however, the vendors are usually prohibited from streets where demand for what they offer is high, as these are under police surveillance.

On El Hoss Street, I spotted a few vendors working on street corners; one was selling coconut and mango, another was selling bananas, and yet another was selling rose water and other products from his village. They informed me that they are sometimes harassed by the police and are at risk of having their goods confiscated. Despite the police threat, they keep resorting to the streets daily to sell their products, as their livelihoods depend on daily sales.

The slow erasure of street vendors and the modernist vision of Beirut

The efforts to remove street vendors from the streets of Beirut were spurred by the market-led urban development pursued by government officials and planners even before the eruption of the civil war in 1975. Since the 1950s, the urbanization of Beirut has been led by private capitalist development and the interests of the real estate market. The state of Beirut’s urbanization prior to the civil war was effectively summarized in a scene from Maroun Baghdadi’s 1975 film Beirut Oh Beirut. In the scene, which takes place in Beirut in 1967, a young activist, Kamal, is discussing with a lawyer plans to evict all tenants from a building that was sold to an American company:

“So they may tear it down?” asks Kamal.

“Don’t you think it’s better to do so” responds the lawyer, “and build a modern building with all the modern attributes that would enhance the area? […] We have to build buildings and roads, give people the life of the 20th century. This is civilization!”

The market-led development under the heading of “civilization,” modernity, efficiency, economic growth, and security persisted and permeated Beirut’s reconstruction in the aftermath of the civil war, which ended in 1990. Urban spaces were stripped of their function as public goods that residents could use for their well-being and livelihoods, and reduced to sterile commodities that could be exchanged in the form of property rights. For instance, real estate development threatened existing public spaces, including Daliyeh waterfront and Ramlet Al-Bayda Beach, which over the years provided vending opportunities and sustainable livelihoods for the urban poor. While some public spaces, including the Corniche and Sanayeh Garden, were refurbished, enclosure, securitization, and surveillance limited their accessibility and usage.

The redevelopment of Beirut’s historical downtown area after the civil war illustrated how economic and state interests converged at the expense of residents’ livelihoods. Before the civil war, Beirut’s downtown had a famous open-air market (souk) area in which vendors sold their products using makeshift stalls; however, after the area’s redevelopment by the Solidere company, vendors were forbidden from using it, and it was put under surveillance by security guards.

As such, city dwellers, especially the lower-income among them, were losing their right to appropriate urban spaces, however temporarily, and make use of them in ways that would meet their needs. Street vendors were slowly and gradually erased from the streets.

The modernist capitalist vision of Beirut essentially entailed displacing and replacing street vendors with large, centralized retail markets. For example, in 2014, the municipality of Beirut launched a project to build a centralized retail market in Kaskas, including underground and aboveground levels with space for 353 shops, storage rooms, an auditorium, restaurants and cafés, a children’s playground, and three parking floors with a capacity of 500 cars. The Ministry of Interior declared that after opening the market, it would prohibit all vendors from selling fruits and vegetables in the streets.

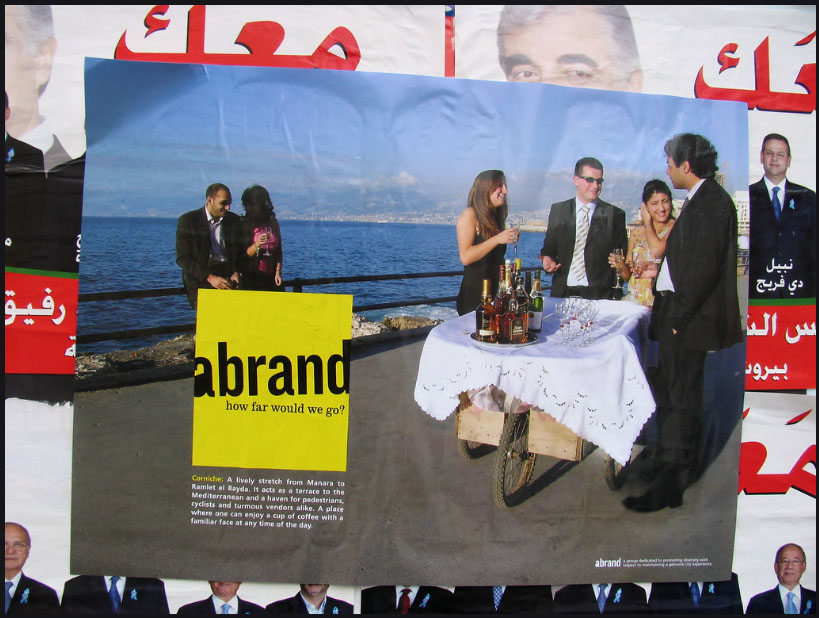

The transformation of Beirut into an elitist city, where the poor lost their functionality and livelihoods, was accurately depicted in a poster by the activist group Abrand. The image showed the familiar Beirut Corniche promenade, which remains one of the few public spaces in the city, transformed into an elite and exclusive setting. Street vendors selling cheap kaak were replaced by a table with a pristine white tablecloth, adorned with vintage wines and spirits and surrounded by Lebanese elegantly dressed in formal evening attire.

Nonetheless, the October 2019 protests allowed people in Lebanon to reimagine and reclaim Beirut, highlighting the vital role of street vendors in the city. Street vendors, usually not allowed in downtown Beirut, sold corn, kaak, party-branded memorabilia, coffee, and cotton candy from carts and impromptu stalls. Hussein Saqr, a street vendor selling corn and fava beans, told Al-Monitor that he had been coming to Riad al-Solh Square daily since the protests began, as access to the area provided him with an opportunity to make money. “I never thought I would be allowed to sell items in this area, which is forbidden to us [street vendors] […] When the revolution is over, I will undoubtedly be unemployed again because the government does not allow us to sell on the streets of Beirut,” he said.

Indeed, when the protests were over, and Lebanon sank deeper into political and economic chaos, the Beirut Municipality accelerated the process instead of recognizing poor people’s claim to the city and facilitating their livelihoods. In March 2022, the Beirut Municipality’s City Guard Regiment announced that it would intensify patrols on the city streets to prevent beggars from panhandling, and street vendors and shoe shiners from working.

Reclaiming streets for securing livelihoods

In the scene mentioned above from Beirut Oh Beirut, Kamal reacts indignantly to the lawyer’s statement on modernity and civilization: “If civilization means to disfigure our traditions and our daily lives, then this is not civilization. Civilization is not in building fancy buildings and big roads. Civilization is to live in an environment where you preserve the authenticity and land. Tell me, if we have your way, who will the neighborhood belong to after a while?”

Decades later, the response to this question was unraveling incontestably on the streets of Beirut: the city did not belong to its lower-income dwellers, and certainly not to street vendors.

As economic opportunities have become elusive in Lebanon, and the government’s efforts to remedy the economic crisis increasingly scarce, the survival of many has been left largely to chance and improvisation — and yet chance and improvisation are hindered when people cannot freely claim their streets and exercise their imagination and creativity in open spaces.

To enable Beirutis to resist and combat economic strangulation, government authorities should recognize the role of streets in securing a livelihood, and vending as a form of employment. Urban spaces would then be released from the grip of capital and given back to ordinary people, enabling them to devise alternative living strategies and stay afloat. Street vendors should be supported rather than erased. As the street vendor I talked to on Hamra Street said, “The police treat us as if we are idle beggars that need to be cleared out from the streets. Vending on the streets is real work and the only way I can secure an income during these hard times. I wish the government would recognize this and allow us to work on more streets.”