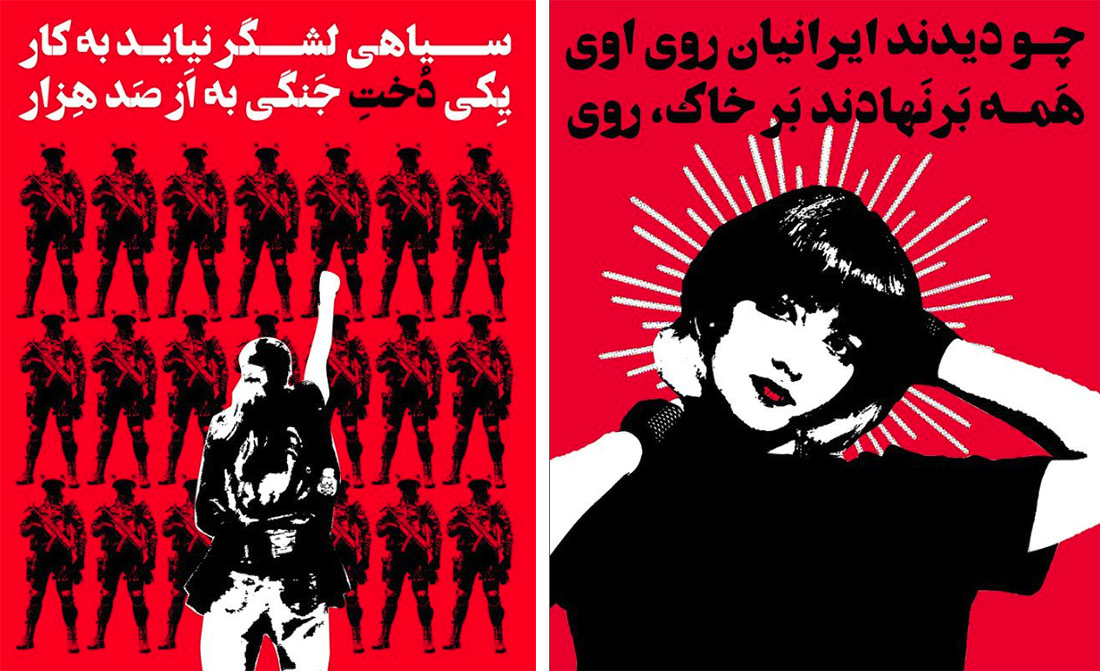

The headscarf that is being waved, banshee-like, by Iranian women is, for the people of Iran, no longer anything to do with Islam but a symbol of the oppression and the abuses that the regime has visited on its own people in the name of religion.

Kamin Mohammadi

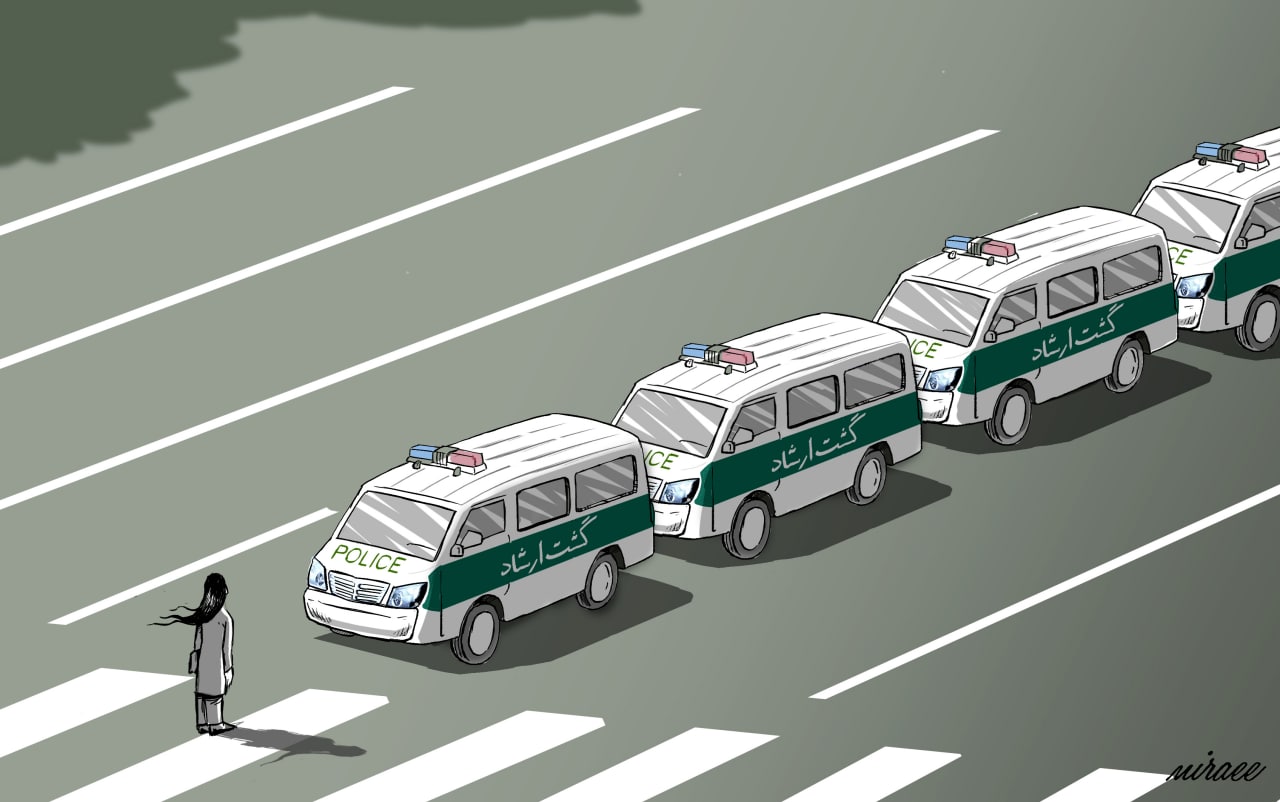

Since September 16th, I have been worse than a teenager with a bad social media addiction. The death of Mahsa Jhina Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurd, apparently at the hands of Iran’s Gashte Ershad or “Morality Police,” and the subsequent protests in Iran have me scrolling through Instagram like it’s a fulltime job. Tracking the protests and what is happening on the ground can only really be done online, since phone lines into the country are not safe and contact via messaging services is also difficult due to the Iranian authorities’ cutting off or slowing down the internet. Cyberspace is now, as it has been for the past decade, the main place where the Iranian people can express themselves. It’s not always a safe space given the Islamic regime’s “cyber army,” but it’s better than the streets which are patrolled by the Gashte Ershad.

After four weeks of watching the most extraordinary scenes being played out on the streets of Iran — ones that even us close observers could not have anticipated — I have had to limit my intake of videos coming out of the country. Showing brutality, the likes of which I studiously avoid on television dramas, the videos reveal an unparalleled use of force and violence against the protestors that makes me sick to my soul.

But as I am scrolling and trying not to click on videos that will break my heart again, I come across a clip of an elderly Iranian lady who is a well-known personality in Iran. She is fully covered in black with unimpeachable hijab and she is crying about the loss of young life at the hands of the regime’s security forces during the protests. And she says something I have yet to hear anyone else saying out loud — by next spring this regime will be over.

I gasp. And a vision rises up before me, one I have not dared envisage for decades now, an image that has been closely put away and almost forgotten somewhere deep in my being. It is a simple picture, of me standing under the plane trees of Vali Asr Boulevard with my hair glimmering in the Iranian sun, leaning in to kiss my man without a shiver of fear, shame and dread running through me. A simple enough image but an impossible dream.

But could it be that next summer, instead of packing my bags for one of the resorts of Europe, I could be heading home? Without the need to pack some sort of hijab? To a free Iran, one in which every step I take is not dogged by fear and a hundred fidgets as I adjust my hijab and look over my shoulder to see who is watching?

What has happened in the past month in Iran is making many of us in the huge Iranian diaspora excavate long-buried hopes and dreams around Iran. Because no matter how long we have been away, and how effectively we have remade ourselves in the image of our new countries, nevertheless every Iranian carries inside them a sort of Platonic ideal of an Iran which is our earthly paradise.

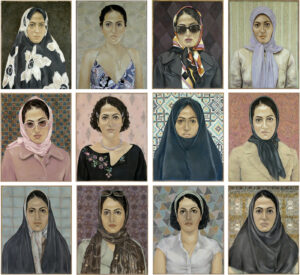

I am an Iranian identified by the hyphen that attaches me to Britain, the country that took us in when we fled the Iranian revolution of 1979. That revolution, now wrongly called Islamic, was in its nature a socialist revolution that demanded equal rights and distribution of wealth. Women were at the forefront and one of the rallying cries was there are no human rights without women’s rights. Yet Ayatollah Khomeini, under whose charismatic populist Islamic leadership the different labor unions and socialist and communist parties coalesced, felt it necessary on taking power to make the first job of his government — “God’s own government” as he called it — to repeal the Family Protection Law of 1975, the most progressive in the region. Given all the urgent problems that revolutionary Iran faced in 1979, it is telling that this was the focus of Khomeini’s first legislature — to take marriage age for girls from 18 down to 9 and take away so many of the rights of women. It was not until 1983 that mandatory hijab was finally made law for all women in Iran — and arguably it was only due to the devastating war with Iraq that started in 1980 that the regime was able to impose this. When I first went back to Iran after 18 years away, it was this hijab and how I was wearing it that became the focus of all my fear, nervousness and worry.

In the 43 years that I have lived in Britain, my relationship with my homeland has been dictated by the vagaries of the regime: did we have a hardline president or reformist? Would I be harassed on the streets or arrested at the airport or left alone? This is a conversation that every Iranian living in diaspora who wishes to visit Iran has with themselves. My passport has been the issue that has haunted my life: on arriving in the UK from Iran in 1979, I will never forget the terror I felt as we stood at passport control at Heathrow and waited for the immigration officer to decide whether we could stay and how long for, or whether we would be sent back to Iran to imprisonment or death. In the decades it took for us to receive our British passports, I became used to not being able to join my school friends on trips abroad and any hopes of going home to Iran were abandoned. At least until we got our British passports, and I could finally stop cringing every time I found myself in front of passport control when we travelled. With the issuing of my British passport, I could also claim back my Iranian one and so, nearly 20 years after leaving Iran, I started to travel back to my homeland every year as an Iranian rather than a British citizen.

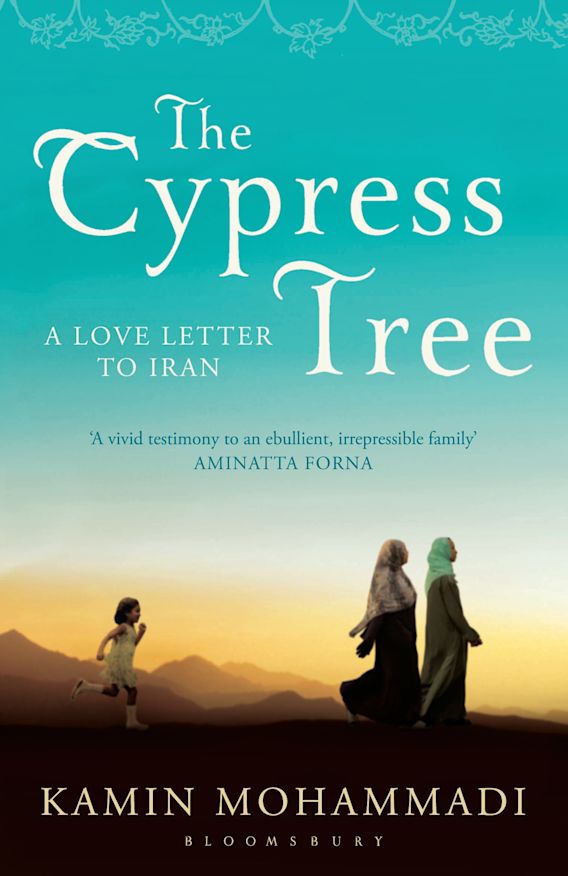

In spite of my nervousness, I started to write about Iran and my trips back soon became an important annual pilgrimage. Travelling on my Iranian passport, my British tucked in my back pocket in case of problems, I would roam Iran with different members of my large extended family, writing articles that sought to humanize the people of Iran and expose the long and sophisticated history and culture of our land to the west. I stopped bothering with taking my British passport when one year someone high up at the British embassy told me that if the Iranian authorities took me, I would be counted as an Iranian citizen and so the UK could do nothing to help me.

The subsequent six-year imprisonment of British-Iranian Nazanin Zaghari Ratcliffe in Iran has borne this out, the years of her life lost to this random incarceration certainly not helped and probably added to by the inept actions of the UK government in that time, especially Boris Johnson’s wrongful declaration, as Foreign Secretary, that she had been in Iran training journalists.

Since my book The Cypress Tree was published in 2011, I have not been back to Iran. Not because I may be arrested for what I wrote. But because the laws in Iran are such that almost any transgression could land you in jail, for charges that are as broad and vague as “offending the laws of God’s earth.” Living in Iran for lengthy periods to research my book, I realized that life there is lived in a kind of fog of deliberate forgetfulness. You live as you wish, of course as discreetly as possible, and you try not to think about the fact that should they so wish, the regime could at any point decide to haul you in for any number of small transgressions that daily life exposes you to, be it the style of your hijab or just the fact that you were in a gathering of both sexes without your hair covered. I became used to going to parties where women arrived looking like black crows with their voluminous chadors (Persian for hijab) and shed them to display the finest of designer fashions and exquisitely made-up faces. I also started to feel a small thrill at the idea that each party could be broken up by the Morality Police and might necessitate a dramatic escape over rooftops or a visit to the local police station. It felt like living with the consciousness that there is a net spread under your feet, so loose and fine that you almost forget about it, but that can be pulled closed at the whim of any local official and trap you within a cross-stitch of Kafkaesque laws that might never let you free.

It wasn’t so much the publication of my book that stopped me returning to Iran. It was more the internal shifts and rivalries in a regime that started arresting dual nationals — hyphenated Iranians like myself — as a way of extorting long-owed money from the west that gave me pause. I felt exposed by that hyphen and unprotected by the government of my adopted country; again, Nazanin’s long incarceration has proved the truth of this.

I now read back my diaries from the days when I lived in Tehran researching my book, when I had an apartment and busy social life and often stepped into government buildings wearing what could be considered inappropriate hijab — not so much the amount of hair showing but more my open-toes high heeled sandals which exposed bare toes and shocking pink nail varnish. In those days, while every official’s gaze travelled silently to my toes, nothing was said or done about it. It was a period in which “bad hijab” was tolerated, a concession to the people who had brought reformist president Khatami in on a wave of hope. Even after the election of hardliner Ahmadinejad, these small social freedoms remained unchanged. My worst fear then was being taken in and having to explain things to my family, inconveniencing them in some way, or having to face the mortifying prospect that my release would be conditional on one of my aunties putting down the deeds of her house, in return for my promise of “good behavior.” I did not fear for my life, for beatings to the head so severe that I would end up in a coma, as Mahsa Jhina Amini did on September 13th, after she was arrested. I did not think then that the Morality Police might rape and torture me before throwing my body from a building to cover up their sins. The fear that stalked me then seems mild to the levels of unthinkable violence that women in Iran have increasingly faced since the election of the hardline president Ebrahim Raisi 18 months ago.

Soon after Ahmadinejad’s first term started though, the harassment of hyphenated Iranians started, and my flat in London became a stopping point for friends fleeing Iran. I got stuck into writing my book and decided not to visit Iran till things clarified. A few years after its publication, when Nazanin was taken and imprisoned on patently made-up charges, I put away the hope I had been harboring of being able to return, or even one day even to live there.

I watched with hope the rise of the Green Wave movement which broke over Iran in 2009, after the disputed presidential election in which Ahmadinejad was reinstalled as president in what seemed clear ballot box fraud. The biggest protests seen since the revolution were brutally crushed not just instantly but, in a campaign of terror that took seven months, its leaders were rounded up and jailed, participants arrested and beaten and intimidated into submission.

Subsequent protests led by women — with men standing alongside them — have been similarly quashed and led to nothing but more heartache. The last burst of angry protests in 2019 led to an internet blackout during which the regime reportedly killed 1,500 people. Whatever hope I had had of helping reform Iran from the inside, of once again calling it home, seemed then to definitively die alongside so many of our wasted young people.

But this movement, which rose out of my paternal homeland of Kurdistan, which uses the Kurdish freedom chant Woman Life Freedom as its central rallying cry, is different. Without an apparent leadership or central organisation, these protests are conflagrations of absolute fury which appear to be bursting out spontaneously all over Iran: BBC Monitoring has recorded protests in 350 locations in Iran. They are led by young women but cut across all genders, age and socio-economic groups. They are centering not just women but ethnic minorities such as Kurds and Baluchis, where protests have been particularly brutally suppressed. As I write, the city of Sanandaj (the capital of Iranian Kurdistan) is under the sort of shelling that recalls the post-revolutionary days of Khomeini, who attacked the region savagely to silent its opposition to his theocratic rule.

It is the facelessness of these protests, their simple demands for human rights, equality and democracy that are remarkable. Their longevity and spreading through university students to high school students. We have seen things in these four weeks that were beyond our wildest imaginings. Schoolgirls with their hair loose taking down the picture of Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khamenei, chasing regime representatives from their school yards, women quietly going about their daily business in Iran without a loose coat or head covering in powerful acts of civil disobedience. We have seen the retaking of public spaces by women who are using their physical bodies — and their hair — to take back the streets, the squares, the school yard, the university campus. These women are overwhelmingly young, but in their cry of fury, I hear the voice of all the women of Iran who have been silenced not just in the past 43 years, but for centuries and for all the generations who have suffered indignity, humiliation and erasure at the hands of “God’s own government.”

While the brutal treatment of Mahsa Jhina Amini over “bad hijab” — and now many other young women killed in these weeks, including 16-year-old protestors Nika Shakarami and Sarina Esmailzadeh — was the spark that lit this blaze of rage. The real heat of this movement comes from decades of repression, a free-falling economy, the mass corruption, mishandled Covid response and hypocrisy of the ruling elite which refuses to allow Iranian women basic freedoms, even as their own children stalk the streets of LA clad in tiny dresses and post pictures of the parties they hold in mansions bought with the pilfered riches of our country.

Living in the diaspora with dual identities has been a balancing act, and I have spent a large part of my adult and working life trying to introduce my countries to each other. Since George W Bush’s “Axis of Evil” speech, it has been a particularly tricky tightrope to walk: not daring to speak out too passionately about the appalling atrocities of the regime against our people for fear of repercussions for our family in Iran, for losing our own ability to travel there safely, and also for feeding the toxic narrative of Iran in the West and enabling an Allied invasion such as those on Iraq and Afghanistan.

And yet, for the first time since we fled in 1979, I feel fully aligned with my people back in Iran. The diversity of the protestors, the acceptance of everyone’s grievances as being equally worthy, the idea that for once, all Iranians are equal in their desire for the same goal — freedom to live a peaceful life with no abuse — makes me and those in the diaspora also feel included.

Even in my extreme privilege in the West, I too have suffered at the hands of this regime. I have lost my country and daily contact and relationship with the people I love. I have had to somehow square myself with the loss of my homeland, mother tongue and direct connection with my culture, I have had to grow accustomed to being “British but…,” to not feeling entirely at home anywhere nor entirely part of any ethnic group. And I too have been dogged by fear since the age of nine since my father’s name appeared on a grave and we had to flee for our lives. Even my journalism and the book I have written about Iran has been colored by fear, and even in my privileged existence of free speech I have self-censored in order to have access to my homeland, to the people I love there.

But now, for the first time in many years I am allowing myself once more to dream that one day I can enter Iran without fear gripping my heart and accompanying every step that I take there. And this heady and delicate little hope has been given to me by the young women of our country, our heroes. Over a decade ago I wrote in The Cypress Tree: “It may not be tomorrow or next year, but I know that the women of Iran will one day take what is rightfully theirs, powered by nothing other than their huge hearts, fierce intellects and sharp tongues.” These lionesses of Iran have at least given us back our ability to dream again, and it is this imagining of a new reality — of seeing it on the streets of Iran as women walk around without hijab — that is perhaps the biggest threat to the continuation of the status quo. Woman Life and Freedom, inshallah.