Nada Ghosn

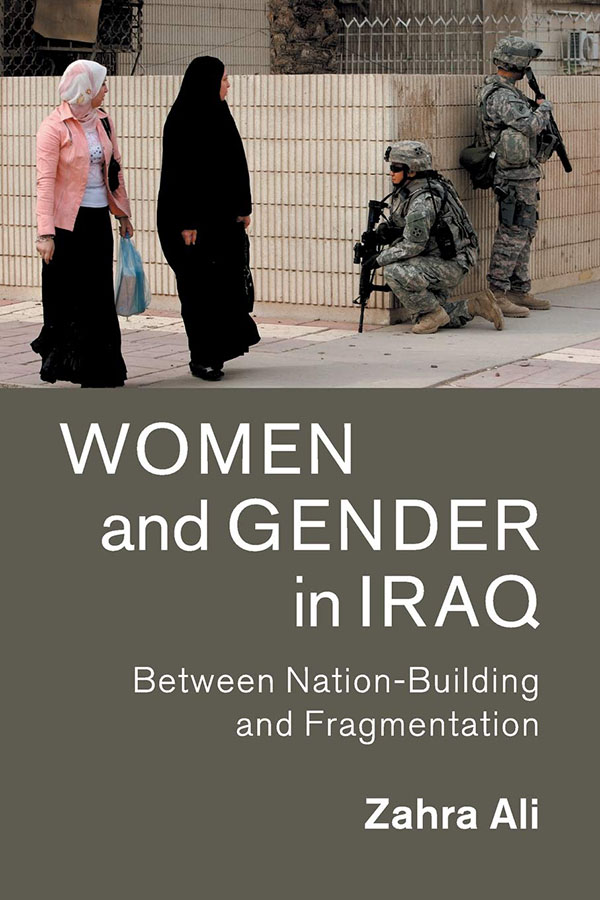

In her book Women and Gender in Iraq: Between Nation-Building and Fragmentation (2018), recently translated into French, Zahra Ali offers an original vision of the feminine question through a decolonial prism that transcends borders and interrogates received assumptions about her country of origin. Relying on academic inquiry and field research, she deconstructs certain categories of analysis, such as nation, Islam, and religious belief, from a feminist perspective that is anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-war.

The daughter of political exiles, Ali grew up in France, in a household that was constantly taken up with the social, political, and economic news in Iraq. “There was always this idea of returning to the country, and all the weight of what it represents to be exiled, or the child of exiles,” she recalled in an interview with The Markaz Review. At the age of 15, Ali became active in an association of Muslim women. Three years later, in 2004, she founded the Collectif féministes pour l’égalité (Collective Feminists for Equality), which pointedly linked feminism with anti-racism.

Her activist approach led her to academic research. She wrote a master’s thesis on the engagement of feminists in France — an ethnography of movements to which she herself belongs — before embarking, in 2009, on a doctoral dissertation in English, from which the book Women and Gender in Iraq emerged. At the time of the book’s publication, five years ago, she was hired at Rutgers University in Newark, and decided to move to New York.

Beyond borders

Ali found herself thriving in America’s largest megalopolis — for Newark, New Jersey is just across the river from New York City. “After five years of living in the United States, my categories of thought continue to evolve in the heart of the empire I so criticize,” she told TMR. “I make post-colonial and decolonial dynamics central to my teaching, and talk about the invasion in Iraq or Afghanistan. I impose an anti-war agenda on a campus where joining the military is the only way to pay for college for black and Latino students, most of whom are from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

Having grown up in a poor Paris suburb and gotten involved in anti-racist feminist circles from an early age, Ali places the concept of transnational feminism at the center of her work. “Unlike international feminism, which implies the idea of being between nations,” she explains, “transnational feminism goes beyond borders to question the concept of nation and to show how it is gendered, racialized, and linked to social classes.”

When she moved to Baghdad, to her grandmother’s house, in her early twenties to begin her dissertation, Ali focused on observing daily urban life. “I wanted to get away from all this writing that gives too much importance to discourse and not enough to materiality. There was a lack of fieldwork that looked at the categories of nation, confessionalism, gender, sexuality, religion, and what they mean in the daily lives of women,” she explains. “It was also necessary to historicize things, going back to the formation of the contemporary state. I opted for an ethnographic approach because it allows me to be as close as possible to the people, instead of imposing categories of thought on them.”

The questioning of dichotomies is central to Ali’s research, starting with the one between the discursive and the material. In particular, she wishes to break with the abstract nature of terms like democracy or women’s rights.

Talking about the everyday allows us to understand the structural dimensions to which these terms refer. What does women’s rights mean when public services and state infrastructure have been destroyed by American intervention and administration? What does democracy mean when the political elite barricades itself in a ‘green zone,’ when citizens are separated by T-walls according to their ethnicity and religion, and when neighborhoods are held by armed militias?

Similarly, talk of secular/religious is meaningless when private affairs are governed by the personal status code, which is based on communal religious jurisprudence. Ali also sees the public/private divide as patriarchal and sexist, as she believes that what happens on the street is as important as what takes place in the home.

Finally, she challenges the local/global dichotomy: the idea that there are feminists “here” (in the countries of the global north) and “there” (in the countries of the global south). “The transnational feminist approach analyzes women’s experiences within the systems of power that structure the contemporary world: colonial, racial, and patriarchal capitalism,” she emphasizes in our conversation . “We all live in the same system, but depending on where we are born, on our skin color, we are positioned as beneficiaries or victims,” she added. “The democracies of the north are based on oil extraction, and Iraqis are feeling the full impact of U.S. imperialism aimed at preserving that system.”

Centering Women and the Poor

Ali did not become involved only with feminist activists in Baghdad, but forged strong connections with many in southern Iraq — Najaf, Kufa, Karbala, Nasiriya, and Basra — to which she travels on a regular basis. “The fact that I’ve lived in Iraq has made my vision of the category of Islam evolve,” she told TMR. “It’s one thing to talk about it when you’re in France, where it’s a minority religion and racialized. But this category plays out differently in a country where Islam is dominant, and the political regime, brought in by the Americans in 2003, is Islamist.”

In the collective work Féminismes islamiques (Islamic Feminisms), published in 2012 under her direction, she brings together the writings of intellectuals, researchers, and activists who pursue a feminist approach within the Muslim religious framework. This book shows that in countries where Islam is the dominant religion, women believers are fighting for equality, turning sacred texts against patriarchy, and speaking out against political and religious authorities that flout women’s rights.

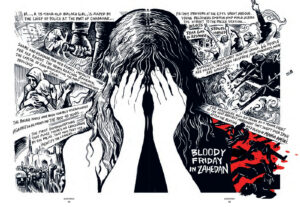

“At the regional level, we are faced with regimes that have politicized religion and confessionalism through gender and sexuality,” Ali says. “In Iran, the simple fact that a woman walks down the street without her head covered means a questioning of the political system. Similarly, in Iraq, during the October 2019 uprising, or Thawrat Tishreen, the mix of young protesters (average age 12-20), with women dressed in different ways, signifies a loss of control by the regime that seeks to control bodies.”

For her, questions of gender and sexuality are at the heart of these new citizen movements: “In recent years, we have seen the emergence of a confluence between the women’s movement and the dynamics of protest. It shows the major role of women in Thawrat Tishreen, the largest popular uprising since the formation of the contemporary Iraqi state.”

This intensification of popular protest movements has moved away from NGO-dominated activism, which is biased toward the experience of middle-class women, according to Ali. “The October 2019 uprising is unique,” she asserts, “because it put women and the poor at the center, a category seen as ‘uncivilized’ by the well-ordered middle class. This mix of genders and classes allowed for the negotiation of a new social contract. And as we see in Iran today, in the face of intensified repression, there is an intensification of resistance and protest dynamics.”