Employer: We are very impressed with your CV and we would love to know, where do you see yourself in 5 years?

Her: With the workers, organizing in the feminist revolution aiming towards smashing the patriarchal, capitalistic, neoliberal, racist, heteropatriarchal violent system.

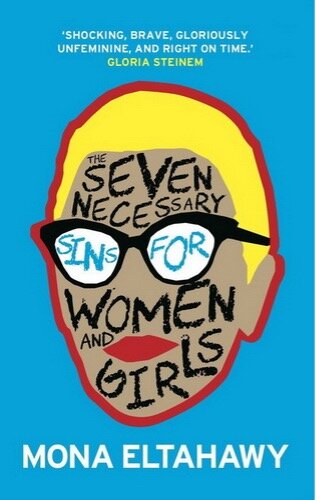

The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls by Mona Eltahawy

Tramp Press (April 2021)

ISBN: 9781916291447

Hiba Moustafa

For those who don’t know her, Mona Eltahawy is a fierce Arab feminist, but she is not the first. As Reem Almowafak has pointed out, Arab feminism launched in the 19th century, and has had many proud activists in several countries, including Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, where most recently one of its greatest contemporaries, Dr. Nawal El Saadawi, died in Cairo at the age of 89. That was also the home base of the Egyptian Feminist Union, founded in 1923, which eventually came under the aegis of the Arab Feminist Union in 1945. Just to establish that Eltahawy has not come out of a vacuum and has had the benefit of major mentors, including El Saadawi, about whom she wrote upon her passing in March (on her Feminist Giant blog):

“Nawal El Saadawi spoke the truth and the truth is savage and dangerous. She terrified and thrilled generations of feminists into unravelling from the binds of patriarchy… It is not the job of feminism to burnish the reputation of patriarchy. It is not the job of feminism to mollify misogynists or placate patriarchy. It is the job of feminism to terrify misogynists and to destroy patriarchy.”

Mona Eltahawy (Photo Rémy Ngamije).

In her latest book, Eltahawy never minces words, for The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls is a call for women and girls to “defy, disobey and disrupt” the patriarchy. It is, Eltahawy writes, a manual for smashing the patriarchy. Patriarchy proclaims it provides protection for women from men. Such provision of protection is conditional on women’s obedience, and a conditional protection is no protection at all. Mona Eltahawy rejects this protection in its entirety; she does not want to be protected; she just wants patriarchy to stop protecting men. She argues that patriarchy is universal and to combat it feminism has to be universal as well.

With biblical irony, Eltahawy presents not Seven Deadly Sins but seven necessary sins women and girls need to embrace to upset the patriarchy — Anger, Attention, Profanity, Ambition, Power, Violence, and Lust. They are sins only in the sense that they are what girls and women are required and expected not to do or even want. Eltahawy gives patriarchy the middle finger as she dissects why those sins are denied to women and girls, and why they should embrace them all.

In Anger, Eltahawy calls on her readers to imagine a world where girls learn that anger is beautiful and a force to be reckoned with — where girls learn to express their anger just as they learn how to read and write and where the anger girls feel toward their own mistreatment is justifiable and even required. Anger can be used as a tool to disobey, defy and disrupt the patriarchy, for instead of being taught to embrace and express their anger, girls are socialized into compliance and acquiescence, into being what Eltahawy calls “foot soldiers of patriarchy.”

Reflecting on her own experiences of sexual harassment and sexual assault as a four-year old girl and a 15-year-old teenager, Eltahawy argues that girls grow into believing that they are weak and vulnerable because “patriarchy is universally crushing [them] into submission.” This explains her reaction to the latter experience by covering herself up with a hijab. Such a reaction is not unique to her; girls all over Egypt wear hijab as a part of their school uniform and even in the US girls are sent back home if their clothes are deemed too revealing or “distracting” to boys. Instead of teaching boys not to assault and raising them into men who should not assault, girls are taught from a young age that they bear the onus of their safety and that it is their fault if they are assaulted.

Available from Tramp Press.

Girls everywhere are forced into subservience under the pretext of girls being weak and vulnerable and boys being strong and powerful, but what is being perpetuated as biological differences are actually a myth; they are social norms dictated by patriarchy. Thinking that patriarchy is limited to conservative traditional societies is another myth; it is everywhere and to fight it feminism has to be as universal. Feminism has also to be more than an abstract idea and it is anger that “carries feminism from idea to being.” The kind of feminism Eltahawy upholds is neither coy nor apologetic; it is “robust” and “aggressive.” As iterated throughout the book, Eltahawy’s feminism defies, disobeys and disrupts patriarchy.

Patriarchy, universal as it is, does not influence women the same way. It is particularly harmful to women in minority groups such as Black women and Muslim women, who are caught between the rock of Islamophobes who do not care about their well-being and the hard place of their own Muslim communities which overlook misogyny so that Muslim men may look good. It is even harder for Black Muslim women who are caught in what Eltahawy calls “a trifecta of oppression: misogyny, racism, Islamophobia.” So to speak, the more the girl or the woman is marginalized the more she will be brutalized by patriarchy. Here, Eltahawy shies away neither from criticizing the two cultures she belongs to, Muslim and Western, nor from offending anyone on either side; she is here to disrupt after all.

Another trifecta influences all women everywhere. It is the trifecta of the state, the street (society) and the home (family). Eltahawy here links the personal to the political. Like June Jordan, a Black poet who has inspired her, Eltahawy argues that the different systems of oppression that affect us individually are actually communal. Therefore, she reasserts, feminism has to be universal in order fight all forms of injustice – racist, sexual, colonial and/or imperial – because they are all interconnected.

In bold and capital letters, the second chapter, Attention, opens with a question almost every woman who dares to act as if she matters hears, “WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?” Eltahawy’s answer is “ME, MYSELF, AND I.” The most subversive and revolutionary thing a woman can do, she argues, is to say that she counts and to “talk about her life as if her life actually matters.” It is revolutionary and subversive because patriarchy requires the opposite of women, to be humble and modest and to take the small space that is allocated to them and be thankful for it. To dissuade women from demanding attention, patriarchy has attached to it the worst insult meant for women, whore, that any woman seeking attention is labeled “attention whore,” not to mention that “seeking attention” is in itself a stigma.

Accused of seeking attention through her protests and activism, Eltahawy declares that she does want attention because what she says and does deserves attention. She welcomes and embraces attention because it enables her to deliver her message to the largest audience possible. Not only does patriarchy shames women for the attention they want or get, it also has a game to play. Like a bone, Eltahawy argues, patriarchy “dangles [attention] in front of women”; if they want much of it, they are called whores and if they do not want it, when patriarchy thinks they should accept it, they are stalked and beaten with it. Eltahawy refuses to play by the rules of such a game.

Patriarchy uses attention as a reward and punishment, a reward given to the women who fulfill certain criteria, especially of conventional beauty, and a punishment inflicted on those who do not by withholding it from them. Taking the form of punishment, attention can be life threatening when women, particularly transgender women, are pressured into fulfilling traditional notions of beauty or when they face emotional and physical abuse, and sometimes death, when they do not ‘pass’ as feminine. Again, Eltahawy refuses to play by any rules and calls for a world where women wait not for attention but create, seize and command it, reasserting that the most subversive thing a woman can do is to talk about her life as if it really matters.

When it comes to Power, Eltahawy argues that matters are more complicated than who is the president or the chancellor for there are many places where power exists and other ways than politics to be powerful. Besides, one has to differentiate between a power that dismantles patriarchy and a power that upholds and serves it. In addition, one has to ask not whether a woman can be president but whether that woman is a feminist, whether she is devoted to dismantling patriarchy and whether she will use her power to dismantle or uphold patriarchy. Attempting to answer these questions, Eltahawy examines the case of Brazil which, though it once elected a woman for a president, has nonetheless remained deeply patriarchal. Dilma Rousseff, the first Brazilian woman president was impeached for breaking budget rules to be succeeded first by her vice president, a center-right man who named all-white, all male cabinet, then by Jair Bolsonaro, an “unabashedly misogynist, racist, and homophobic former army captain” who became president in 2018 of a country that only ended military rule in 1985. Eltahawy expands on how some men, including Bolsonaro himself, set in motion Rousseff’s fall. However, it is not only about Rousseff. Eltahawy argues that in a country whose elected president told a member of Brazil’s congress that he would not rape her because she did not deserve it is a country where women can never be safe. It is also not just about one man or patriarchy alone; it is about an entire system where patriarchy is in the works with “militarism, capitalism, authoritarian Christian values” and where women sometimes join the ranks of men as “foots soldiers of patriarchy.”

How does patriarchy get women on its side? By promises of protection, but these promises, Eltahawy argues, are false and if any protection is provided it comes at a price. To ensure white women’s allegiance and obedience, patriarchy and white supremacy tantalize them with promises of protection be it from black men, brown men, immigrants or any other imagined danger. Patriarchy also gives women crumbs of power in return for their obedience. Eltahawy argues that women have to refuse those crumbs since the goal of feminism is not to elevate some women in the hierarchy of power but to dismantle patriarchy and other forms of oppression. That some women gain access to power does not automatically mean all women are empowered; women in position of power can themselves perpetuate patriarchy and other systems of oppression.

On a more personal note, Eltahawy recounts how she and other men and women challenged the balance of power in 2005. Back then, Eltahawy joined the first mixed-gender Friday prayer led by a woman, Amina Wadud, an Islamic studies professor at Virginia Commonwealth University at the time. Reciting verses that address the equality of men and women and giving a sermon about how male jurists excluded women from the codification of Islamic law, Wadud waited for no one’s permission to offer her own interpretation of Islam and a woman who does not wait for permission, Eltahawy argues, is a powerful woman. It was not unexpected therefore that Wadud received hate mail and death threats in the days that followed the prayer because patriarchy is thin-skinned and takes any declaration of power by women to heart. The fact that nothing in Islam bars women from leading mixed-gender prayers proves just how patriarchal interpretations of Islam have taken root over centuries to the benefit of men.

Many religions are patriarchal, Eltahawy admits, and a feminist no matter her religion has to fight patriarchy in every space and from within and without religion. Things are not as simple as leaving one’s religion; patriarchy is universal and exists in secular spaces as well. Therefore, dismantling patriarchy has to continue on both sides, the religious and the secular. Sometimes, the secular works hand in hand with the religious to police women’s bodies. The starkest example is menstruation. In many religions, women are forbidden from praying or entering religious places while menstruating. Referring to the #RightToPray hashtag, Eltahawy explores how women in India fought to gain access to Hindu temples that for centuries have been barred to women and girls of menstruating age. Women are always told that they have to wait, that there are more important issues at stake, and that there are other forms of oppression that deserve more attention.

Though Eltahawy admits that there are too many forms of oppressions to fight, she asks why women have to wait. Telling women to wait means that they are not important and she is willing to continue fighting this trifecta by “defying, disobeying, and disrupting patriarchy in the state, the street, and the home.” To do that, women have to seize, define and reshape power. They have to imagine a better world without waiting for any man’s permission for only then they can be free.

Shocking is the least that can be said about the opening to the book’s penultimate chapter. In Violence, Eltahawy calls on the readers to imagine the following: an underground movement called Fuck the Patriarchy (FTP) launches a systematic, en masse killing of men for no reason except that they are men. They do not want money, they do not want to change a government, they do not want a pay raise, they do not want parliament seats and they do not want men to promise to do laundry or babysit their own children. They want patriarchy dismantled or they will continue to kill men. If this is shocking, be ready for the unsettling questions Eltahawy asks. How many men would be killed before patriarchy is dismantled? How long would it take before the world pays attention to the killing of men? How long would it take representatives of patriarchy to hold a summit to put an end to the killings? How would men feel to see their fellow men so killed? Would men change their behavior? Would boys be brought up a different way?

Why is this scenario shocking in the first place? Is it because violence is strictly a male domain? Is it because women are and should remain the only target of violence? Violence against women and girls happens every day and if every single incident of violence against them was reported, it would be recognized for what it truly is, an epidemic. Yet, the violence women and girls face does not shock the world; on the contrary, the world teaches them to live with it and not to fight, but fight they should, Eltahawy declares. One of the ways that violence against women and girls is not recognized for what it is truly is that it is portrayed as the exception rather than the rule, as if it were committed by psychopaths and not by ordinary

men, but it is committed by ordinary men: fathers, husbands, partners, boyfriends, brothers and sons. That men distance themselves from violence by pretending it is only done by psychopaths is exactly why it never stops.

Eltahawy opens the final chapter, Lust, with a fierce declaration that she owns her body, that her body belongs only to her, that it is her right to have consensual sex with whomever she wants, whenever she wants, and that she has the right to express her sexuality in any way she pleases. Such a declaration is revolutionary, Eltahawy argues, because it defies, disobeys, and disrupts patriarchy whether that patriarchy takes the form of the state, the street, the home, the temple, the church, or the synagogue as each of these entities think it owns women’s bodies, or in Eltahawy’s words, the body of anyone who is not a cisgender, heterosexual man.

In a deeply personal narrative, Eltahawy recounts her struggle over the years to own her body and sexuality, admitting that patriarchy imposes heavier burdens of purity and modesty on women and girls than it does on men. Still, she argues, patriarchy has a strict definition of how and what to be a man, a definition that excludes any man who is not “a conservative, heterosexual, married man” and that man always belongs to the most powerful group in any country or culture; it is the powerful who set the rules, after all. Such definition of what a man is not only is associated with men in power, Eltahawy argues, but also with masculinity that is invested with power. Femininity on the other hand is invested with weakness and inferiority, thus patriarchy narrows gender binaries and to revolt against those binaries is a rebellious subversion of patriarchy.

The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls is revolutionary and unapologetic, and Eltahawy does not flinch from saying what she has in mind even if it disturbs or disrupts the way things are.

Follow Arab feminists on Twitter:

Alaa Al-Eryani (Yemeni): @YemeniFeministM

Mona Eltahaway (Egyptian): @monaeltahawy

Zainab Fasiki (Moroccan): @zainab_fasiki

Joumana Haddad (Lebanese): @JHaddadOfficial

Loujain Hathloul (Saudi): @LoujainHathloul

Rula Jebreal (Palestinian): @rulajebreal

Emna Mizouni (Tunisian): @EmnaMizouni

Samar Yazbek (Syrian): @SamarYazbek