Farah Abdessamad

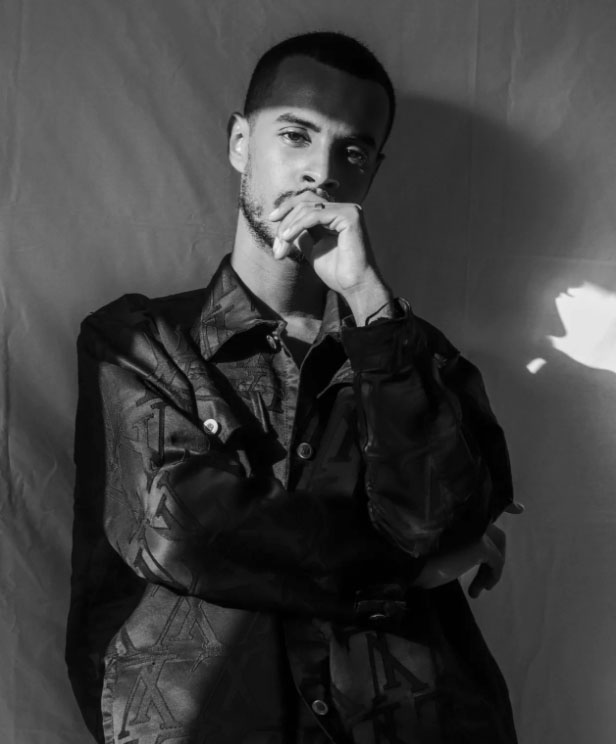

Yemen-based Adeni artist Asim Abdulaziz (b.1996) is obsessed with one question: what has war made us become?

The artist’s question lends itself to an appraisal of the effect of violence and trauma on human lives. As a result of seven years of continuous war in Yemen, which by the end of last year the United Nations estimated had caused upwards of 350,000 direct and indirect deaths (from famine and disease), and with the backdrop of a fragile UN-brokered truce, Abdulaziz chose to explore this complexity using an experimental form. His 1941 is Yemen’s first experimental film. It discusses masculinity, agency, liminality, and the value we ascribe to time and place.

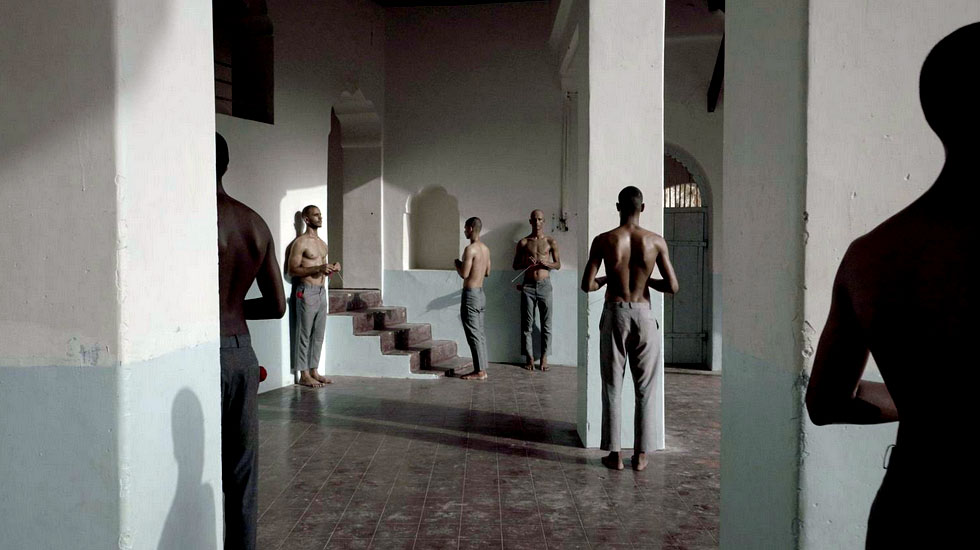

Without any dialogue, the film opens on a cloudy sunrise. We recognize Aden’s volcanic mountains and, soon after, a building appears nested against the rock. This single location — a 19th century Hindu temple — is where men mechanically knit with red yarn.

Different scenes depict the multilayered, sensory forms of trauma-generating alienation in solo shots and group settings. For instance, young men knit in unison while walking down the temple’s beautifully-carved wooden staircase. They look alike — closely shaved heads, shirtless, with grey slack pants. Their hands animate as in a choreography, obeying to an invisible urge to commune. Their walk is stiff, soldier-like.

While the characters are seemingly constrained by their own inner torment, they move together. Their destinies and shared experience sometimes binds them in more intimate ways — literally. A sense of inextricability arises when two characters have their heads conjoined and wrapped in red yarn. The threads are pulled with arachnid patience; their layers channel the sacredness of a mummification process.

Narratively, the film follows a non-sequential suite of symbolisms touching upon inter-generational trauma, mixing old and young characters. No one is spared from a haggard existence. While a boy awkwardly learns to manipulate his knitting needles tightly framed by a suffocating window, an older man with a salt-and-pepper beard observes his long scarf. He’s experienced a great deal and we think not only of the most recent conflict but also of the civil war in 1994.

The characters avoid staring directly at the camera. We hardly identify them and in some cases, a decoy such as a rock masks their faces. In doing so, Abdulaziz remind us of an indiscriminate quality. Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress can affect anyone. The body hosts these psychological assaults. Along with inserted cuts showing the decayed appearance of the building’s walls, the film presents a physical allegory of fragility.

The knitting balls that populate the film are the external projections of ruminations, meanderings, and the haziness of resilience. In one room, they hang from the ceiling without touching the floor — suspended, incomplete, vulnerable. Windswept, they evoke a sense of floatation, uprootedness, and challenge the possibility of firm anchoring.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

Abdulaziz came cross an article in 2020 recalling a cover of Life magazine from November 1941, which described knitting as a war effort during the WWII. This article led came to influence his film’s title, 1941, and for the artist to reflect on utilitarianism, distraction, and emotional expression. “In Yemen and in the Middle East, men aren’t allowed to express their emotions. They always need to be tough and emotionally detached. But in fact, what I realized when I returned from Yemen after living in Kuala Lumpur for four years is that men also have emotions and they can experience depression and anxiety,” he told The Markaz Review. Upon returning to Aden in 2019, he immediately noticed people’s empty gaze.

The cinematography created by Abdulrhman Baharoon embraces visual contrast, from Aden’s luminosity to the cavernous insides of the temple, from the building’s mint and white-painted walls to the splash of red yarns against the characters’ neutral-warm tones. The characters sometimes double like mirrors, twins, and clones. Their stillness combined with the dynamic act of knitting offer depth in how we understand movement and the hyper-sensorial ways of living in the world.

To where does the staircase lead and does it allow any escape? And what are these sounds made up of what seems to encompass metallic needles clicking against each other, locusts, and a print room? In this rhythmic white noise of percussions and buzzing, the film reinterprets aerial bombardments and the commotion of war.

1941 embodies time, incarnated in the physicality of a building and in these bodies. Abdulaziz searched for a location for over five months until he remembered this Hindu temple in Khusaf, near Crater, one of several historical heritage sites that still stand in the diverse city that prides itself for its tolerance. “The temple represents Aden, beautiful but neglected. It’s the city itself,” Abdulaziz said.

The temple assumes multiple functions. In our imagination, it can be a hive, sanctuary, asylum, sanatorium. Time can feel diffracted and endless, such as when figures follow each other in circles, or a more linear, for instance in the old man’s long scarf. Time can be insidious and a thief; men knit in their backs, unconscious of what their hands produce.

The film poignantly reasserts a form of slowness in various propositions on temporality as a form of solace, necessary acceptability, and torture. Simplicity, in décor and motion, is an artistic tool. “I always try to produce art and films that have a simplicity that reflects Yemeni life that outsiders might not know much about,” Abdulaziz said in a recent interview with the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

⬪ ⬪ ⬪

In focusing on the human scale, Abdulaziz tries to understand how war shapes and transforms — an event seen as a disorientation, numbness, and nudge. “We are still facing a war, a psychological war, living under threats. For example, in the past two months we have experienced three car bombings, including close to my office. War is not about having an army that comes and attack another city. For me it’s about feeling unsafe,” he said, noting the daily hardships and shortages that Adenis continue to face.

1941 reminds of the artist’s previous photography work, Untitled (2019), in which he peels potatoes blindfolded among rubbles. The artists see his first film as a “shift” using another medium to relentlessly interrogate psychology and men’s emotional density.

The film premiered at the Canada Short Film Festival in 2021, where it won distinctions in Best Experimental Film and Best Cinematography. Abdulaziz was recognized as Best Karama Yemen Human Rights Film Festival (2022) and Best Independent Film at the Spotlight Short Film Awards (2021). It also features at the 12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (2022).

Around one in five people in Yemen suffer from mental health disorders according to a 2017 study, a figure likely underestimated given existing stigma and the difficulty in accessing mental health care services. Dr. Bilqis Jubari, the founder of Yemen’s first public mental health service in 2011, thinks it’s closer to one in three.

There are fewer than 50 psychiatrists in Yemen and only four public psychiatric health facilities across the country. In the absence of accessible healthcare, it’s not uncommon for people to cope with anxiety and insomnia by consuming more qat and adopting other risky behaviors. Depression, gender-based violence and suicides are on the rise since the start of the war. Years ago, I visited an institution in Aden which kept people suffering from mental health disorders in cages; many of them were shackled to their beds. And customary beliefs often prevail, assigning a mental health condition to being possessed by a djinn.

“A lot of people misunderstood my ideas. They didn’t see them as serious topics to be discussed. But the more they see my work, the more they start to understand and support my work,” Abdulaziz said.