These days, with rampant attacks on intellectualism everywhere, teaching theory necessitates a vital ethical imperative for public intellectuals who can speak in many registers.

Deborah Kapchan

When I was a student in the early eighties, I put myself through school in New York City waiting tables in a series of French restaurants — La Crêpe, La Bonne Soupe and another whose name now escapes me. I was a literature student at NYU, minoring in French, at a time when that university was primarily an affordable commuter school (and not the prohibitively expensive corporation it has become).

I was completely independent at 18, filing my own W2s, and so received the maximum amount of financial aid from the state and federal governments. But I still had to pay the rent on my studio on East 6th Street, to cover utilities and buy my food. Working at French restaurants allowed me to supplement my income while practicing my French with the expatriate staff. I worked three nights a week, reading Stendahl, Baudelaire and Artaud during breaks, and devouring the films of the French New Wave on my days off.

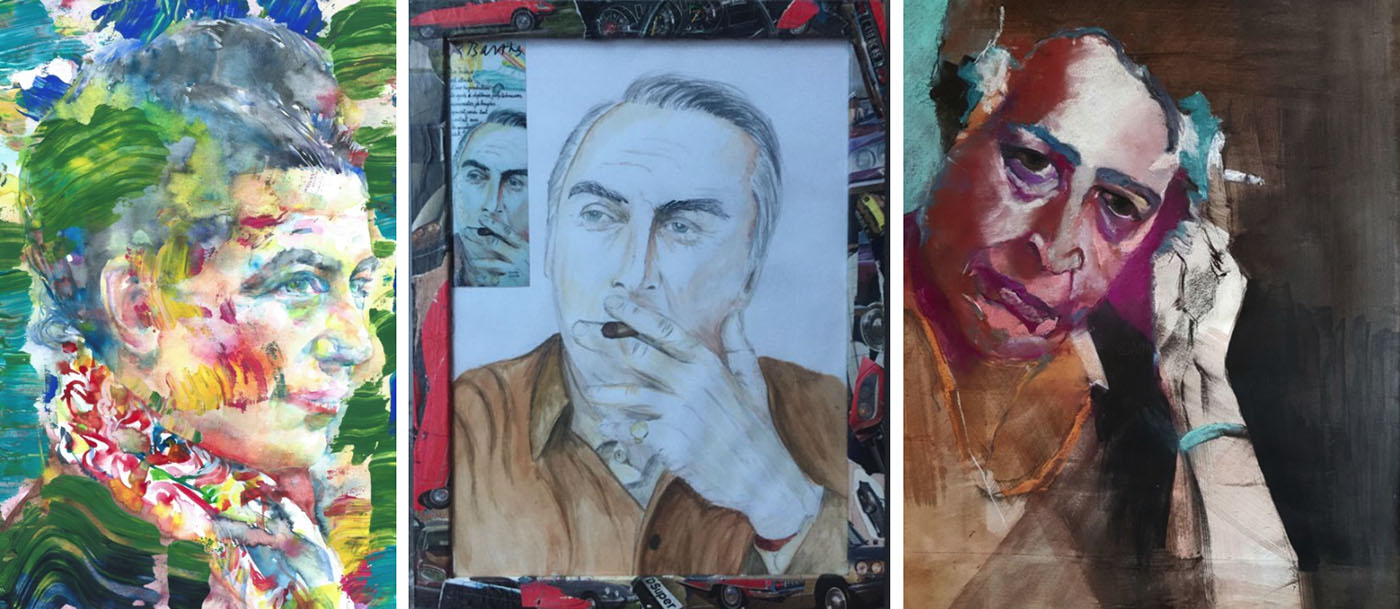

In the 1980s, a degree in literature was also, if not primarily, a degree in social theory, and it was the contemporary French public intellectuals that influenced me the most: Barthes, Cixous, Derrida, Foucault, Irigaray, Lacan, as well as Beauvoir and Sartre. Only later would I discover Bourdieu, Bachelard, Bergson, Kristeva, Lévinas, Lévi-Strauss, Lyotard and Merleau-Ponty. The ideas in these philosophical and psychoanalytical texts excited me, not only for their authors’ novel and creative uses of language, but for how these thinkers engaged the contemporary world, providing a way to understand power and patriarchy. Social theory was an intellectual method for recognizing the narratives that shape society and the individuals within it.

I became a theory junkie, devouring all I could. Little did I know when I was walking the halls of the Silver Building in 1982, that I would be hired as a professor there 30 years later (after a 10-year stint at the University of Texas), and go on to teach the ideas I had encountered decades before.

Like Gauguin’s painting, “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” theory asks big questions. From the Latin word, theria, to see, theory allows us to step back and observe the human condition and to critique the ideologies and perspectives that blind each and every one of us to our own biases as well as the viewpoints of others. Theory gives us the tools to recognize what we don’t know, and to cultivate what we could be if we became more conscious.

But theory is often incomprehensible, even to one well read in literature. It is full of jargon and sentences that go on for a full paragraph. As a young person, part of the charge of reading theory was the ability to enter into the foreignness of its language, to struggle with the words until I found the key that opened the concepts and illuminated both the minds of the writers and the realities on which they reflected. But teaching theory taught me something else: the necessity for translation, and the vital need for public intellectuals that can speak in many registers.

I took great pleasure in teaching Bourdieu, for example, in explaining his concept of habitus. From the Proto-Indo-European root, ghabh, “to give or receive,” Bourdieu draws on its later associations, “to have, hold, possess; wear… to dwell, inhabit; have dealings with.” But the most salient resonance, for anglophones at least, is the word that inheres in the Latin: “habit,” as in something one does regularly, without thinking. Something second-nature, a practice.

In his own words, Bourdieu defines habitus as “structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures.” Can someone help me here? At first glance, that sounds like a tautology, but in fact, it is simpler than that: habitus is the culture we inhabit, the water in which the fish swims. We don’t see it. It is not conscious, but our practices create it in every moment. It is shared, but it is enacted by the individual. It makes us, but we are always reproducing it as well. The concept of habitus explains the subtle connection between the social and the individual, between the mind and the body, between what is determined for us (what religion calls predestination or fate) and what we create (free will, agency). Habitus assumes that the human is born into a world that is given — class, religion, race, gender norms, the way we eat and dress, what we desire — but it does not preclude the possibility of transformation, of breaking out of structure. After all, there is change. In order to enact it, we must begin by seeing the webs that ensnare us in the first place and our complicity in weaving them.

There were many key concepts I culled from social theory and used in my teaching. Foucault’s metaphor of the panopticon is probably most iconic. Taken from Jeremy Bentham’s study of a prison in the round in which the prisoners never knew when they were being observed by their captors, Foucault demonstrated that domination works best when the dominated discipline themselves, internalizing the gaze of those with power — whether prison guards, the state, or cultural and gender norms meant to control who we are.

What I learned by teaching these and other often difficult texts, is that a public intellectual is first and foremost a translator. (Roland Barthes did this in his essays, taking the practices of everyday life — wine-drinking, wrestling, advertising — and revealing them as cultural myths.) Social theory is a language, and only those who want to learn it, sign on. But we make a mistake if, once we become fluent, we only speak to the initiated. In 2023, when reading is on the decline, attention spans waning, and critical race theory under attack, this is especially dire.

Name-dropping is something one can do in theory: Bachelard, Barthes, Beauvoir, Bergson, Bourdieu. These are the Bs in my own personal canon. (For more contemporary theorists of race, gender and ecology, let’s name Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Saadiya Hartman, Donna Haraway, and Fred Moten; and in France, Bruno Latour, Catherine Malabou, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Rancière, and Michel Serres.) “In theory,” one can name-drop when talking philosophy, because the reader is supposed to have read deeply in the tradition and each name resonates with its ideas and its history, which is precisely why it is a closed discourse. In theory one can drop names and metonyms, while in public discourse that is pedantic. These are two different genres, governed by different laws.

But, as Derrida notes, the law of genre is meant to be transgressed. The boundaries of genre, like the boundary of any category (woman/man, black/white, nature/culture) do not hold. To translate is to trespass, to go beyond the borders, to recognize multiple worlds and to make them, if not transparent, then mutually intelligible.

I have come a long way from waiting tables in French restaurants. On the other hand, that is the habitus that formed my foundation: working class, upwardly mobile, hungry to create worlds I could only access through education. Social theory led the way forward and out. These days, attacks on intellectualism are everywhere and dangerous. They presage anti-democratic trends and ultimately fascism. In such a world, translating ideas into other registers is not a dumbing-down, but an artful craft and an ethical imperative. Social theory, including critical race theory, is as necessary as breath. But training students to translate both ideas and their own habitus must be part of every author’s curriculum.