Omar El Akkad

In the summer of that final year, Sheikh Hamad’s daughter turned thirteen and they built her a private schoolhouse on the grounds of Doha College. That same summer, Mo’min Abdelwahad got braces.

He didn’t know why he needed them. Something to do with curvature, a word his dentist used: They were not bad teeth, not hopeless, she’d said, but wouldn’t he like a better smile? Mo’min had never considered the quality of his smile before.

He’d managed to keep his composure during the consultation but after they left the dentist’s office, he started crying. The previous winter a classmate of his named Armand had gotten up to retrieve a math test from the teacher’s desk without noticing a wayward erection. Someone had given him the nickname Kharmand and it had stuck. Mo’min was thirteen and these were bad years to be anything but anonymous. There was no surviving attention.

On the drive home, Mo’min’s father said back where he grew up, in Shobra, your teeth did whatever they did and nobody did anything about it. Once when he was young he’d felt a tilapia bone go right through his gum, the pain so sharp he thought he’d throw up, and the only thing his aunt offered by way of remedy was a teabag to chew on. It’s easier these days, he said, it’s easier here.

It was noon on a Friday, the streets empty, the mosques filling. On QBS the Whigfield song cut out mid-note, a muazzin replacing it, and Mo’min felt, as he always did in moments such as these, a little guilty. Outside of Ramadan, when suddenly every breakfast was communal and came with the social obligation to perform the sundown prayer at whomever’s house they were invited to that day, he only ever prayed on Friday — usually with his father at the mosque down the street from where they lived. It had been explained to him from early childhood that this prayer was special in some way, worth more in the grand accounting of things in part because it was done in such large groups, but in truth he’d only ever associated the Friday trip to the mosque with the end of the weekend. For the rest of his life, even after decades in the West, he’d always have a hard time associating Monday, not Saturday, with the start of the workweek.

His father said it was okay to skip prayer today. They went to Baskin-Robbins instead.

In early July Mo’min went back to the dentist’s office for the procedure. The only part that hurt was when she inserted the wire. He felt the contours of his mouth tighten, and for a few days afterwards his jaw ached the way it did during those first few bites of breakfast on mornings when he slept in too late. He imagined it was the pain you felt when you got punched, but he’d never been punched before. In English class that year, they’d been forced to read a book about boys stranded on an island and he felt now a kinship with those boys, though he couldn’t quite explain why.

Fall came. In early September, it rained for the first time that year and on the evening news the anchor led with thanks to the Emir for his fruitful supplications. At school, a few of the upper-year boys made fun of Mo’min but it wasn’t as bad as he expected. Anders, who was two years older and lived in a suite in the Sheraton where his father was manager and normally wouldn’t have wasted time on some kid in 7P, passed him in the hall one day and said it looks like the Bedouins up in Shamal are going back to their tents with scraped cocks tonight. Later, at first break, another boy in Mo’min’s small orbit of friends choked a little on a bite of tuck shop brownie and Mo’min, seizing the opportunity, repeated the line Anders had said to him, and though or perhaps because it made no sense at all it got such a rousing response from the other boys that Mo’min briefly considered going to Anders and thanking him.

Months passed, and he disappeared as he’d hoped he would, happily avalanched under the school’s endless supply of gossip. In October Miss Lordes and Mr. Polk ran off together to Australia and left that year’s graduating class suddenly forced to do two years’ worth of GCSE coursework in a semester and a half. Some parents complained, and one threatened to sue, but the chances of either teacher ever returning to the country were known by all to be, essentially, zero.

In November, it came out that Mr. Park, the graphic design teacher, had been sleeping with one of his students. For a while there was another rumor affixed to the first, a rumor of pictures that had been taken and possibly distributed, but this turned out to be a lie. Khalid, who was in 7P but had an older sister in one of Mr. Park’s classes, said it didn’t really matter either way: both teacher and student were British and the British don’t care about stuff like that.

In December, Tamim and Lina started dating. Soon the teachers charged with patrolling the yard during first and second break learned never to go near the concrete alcoves round the back of the physics labs where the two spent all their free time. There were rules against physical contact between students, but no teacher was willing to risk their work permit to find out if those rules applied to the Emir’s son.

Then in January, Tamim’s sister came to school. She was Mo’min’s age but he never learned her name.

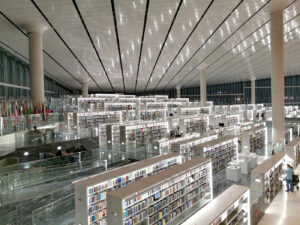

For the better part of a year there’d been construction going on by the school’s east-facing wall, hidden away behind plywood and canvas. Someone said it was a new technology building but nobody could figure out why Doha College needed yet another suite of sewing rooms and home economics kitchens to teach students the things their housemaids already knew how to do. And then in the new year Mo’min returned to find a small neighborhood of trailers, guarded by police officers along its streetside gate. In the morning, after the rest of the students had gone to first period, a parade of black-windowed Mercedes sedans pulled up to the new construction, and the Emir’s daughter walked into her own private schoolhouse.

By February, everyone had a story about how they’d seen her but almost no one really had. Someone said her name was Mozza or Manga, but someone else said it was her mother, not her, who was named after a fruit. She was stunning and hideous, useless at school and three grades ahead, and ranged in age from ten to nineteen. No one in Mo’min’s orbit knew anything for certain or cared to find out. After school at basketball practice one day Anders said it was just her and Ms. Demitri in that compound all day, fingering each other dizzy. Mo’min had no idea why they’d be in there doing that, but the image of the school’s biology teacher and the Emir’s daughter sitting in a room pointing at one another until both keeled over struck him as funny in an absurdist way. The next day he repeated the joke to his friends at break. They found it funny too.

In March, it rained again and all the big streets flooded.

He had a few days off school. He spent most of them at Al Naseem, the compound where he lived. There was nothing to do. Sometimes his mother would tell him to go swim in the compound pool or play in the squash or tennis courts or go for a bike ride, but it was already getting too hot to do anything outside any time between noon and sundown. He spent the days watching MacGyver and America’s Most Wanted on QTV and wondering about what kind of place America must be. He read his parents’ copies of Time and Newsweek, holding the pages up against a lightbulb to try to see past the government censor’s ubiquitous black ink, the smudged shapes of women in miniskirts or Israeli politicians all so tantalizingly close to visible. Toward the end of the month his father went to London on a business trip, and came back with a smuggled copy of Sliver on Laserdisk. The film was indecipherable to Mo’min even after the tenth time he watched it.

One morning his father took him for a drive out past the edge of Doha, into the desert, where clear of all other construction a single house stood seemingly without place or purpose, an aberrant thing. In the sanded clearing ahead of the house’s front door were parked various breeds of Mercedes and Land Cruisers. His father parked near these cars and told Mo’min to wait. He went inside and when he returned a few minutes later, he carried a mango crate full of beer and liquor. Other men did the same, rushing out the door with their heads down, eager to leave the house and the desert that wielded its emptiness like an anvil on the chest.

In April, Mo’min went back to the dentist who said the treatment had worked much better than expected. After less than a year the wires came off and for a few days he felt the same fortifying pain in his jaw and believed now that yes he had been through something, had become tougher for it. He saw no difference in his smile, but his mother said it was straighter, more appealing.

Gone down the narrowing funnel of exam period, the students careened through late spring and into the hot glowing days that would forever mark Mo’min’s memory of this place. There was less to do now but study for the end-of-year, finish up coursework. In early May he finally worked up the courage to ask a girl named Aysha if she’d go with him to the newly opened A&W but she said no. He went to the Dubai team try-outs and did all right in basketball, but Mr. Frome said they needed all-rounders since they could only take so many students on the trip. Still, it felt good to try for things, to build callouses against rejection.

The only person at school who’d noticed Mo’min’s braces had come off was Anders. One day in the hall the two of them passed and Anders said I guess those Bedouins don’t have to worry about getting their cocks all scraped. And Mo’min, before he caught himself, replied: I bet you’d know what that’s like, which only later he realized was a non sequitur but still caused Anders to stop anyway and observe Mo’min not with anger so much as genuine surprise. And then Anders smiled and Mo’min, believing they’d shared a moment of something like camaraderie or mutual respect, smiled back and Anders gracefully, almost as though the motion were rehearsed, took two quick steps toward Mo’min and flicked the upper row of his newly realigned teeth. Fireworks shot up through Mo’min’s gums, for a second he saw them as little white bursts against the field of his vision, and by the time the pain subsided, Anders was gone. The bell rang, sounding the end of second break.

All around him students began to return to their classes. For the first time, he experienced claustrophobia. The thought of sitting through another 80 minutes of tedium felt suddenly unbearable.

He had never skipped class before. He’d seen the upper-years jump the gate, hop in those boxy orange-and-white taxis and take off, but had never thought about doing it himself. Now, the pain in his mouth gone, he did. The day’s last period was double science. Mr. Ballard never took attendance.

He waited out the bell by the east-facing wall, near the place where Tamim and Lina spent their time but far enough away from the physics lab windows so as not to be seen. In a few minutes the students had all returned to class. There was an ugly silence about the yard. In the distance he heard the Indians and Pakistanis and Filipinos working on the rugby club building, the sound of metal on metal, the occasional shout: Yallah, rafik, yallah, no lazy, make work.

Quietly he walked toward the school’s front gate, unsure of whether he’d be able to get out unnoticed. Lacksman, the custodian, manned a small outbuilding by the front but someone said he spent most of the afternoon sleeping away the heat.

Before he got to the front gate, Mo’min heard a sound on the other side of the wall. It came from the new block of trailers, the hid-away place. It was a soft squeak, a repeating sound. Instantly he placed it as the chains on a poorly oiled swing.

Without thinking he climbed onto a stack of wooden crates, in which had recently been delivered a new set of sewing machines for the technology building. He peered over the edge of the concrete wall.

She was a small girl, her posture cashew-rounded as she sat rocking gently on the swing. In Doha College, the A-level students wore white dress shirts and black pants or skirts and everyone else wore shades of light and dark blue, but she wore neither. From the way she sat he couldn’t tell if it was just another niqab or a black dress. She stared at her feet.

And then she looked up. She looked at him without expression, no hint of fear or shame or warmth or curiosity. It was not a poker face so much as a face that seemed unaccustomed to the mechanics of such interaction, the ways in which the muscles move to signal recognition of another, acknowledgement.

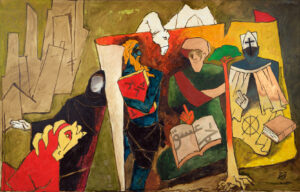

In the few seconds before he heard the sound of the teacher behind him, Mo’min stared at the Emir’s daughter the way, years later, he’d stare at the grounded paintings in the basement of the National Gallery, the ones the curator let him inspect one night in a burst of indiscretion but which were otherwise locked away for reasons of suitability or fragility or internal politics, and which for the life of him Mo’min couldn’t tell apart from all the paintings that hung in the gallery proper, one bowl of fruit no different than any other.

He smiled at her.

And then there was the voice of Miss Demetri behind him: “Are you out of your mind?”

He hopped down from the crates, half-stumbling. He apologized but Miss Demetri only said, over and over: “Are you out of your mind?” He had never seen a teacher behave that way before, so visibly, plainly afraid. She led him to the principal’s office, walking three steps behind him the whole way there, as though he carried something contagious.

The next day he was marched again to the principal’s office and told never to speak about what had happened, never to tell anyone. With great solemnity the principal said if word got out he risked expulsion and although the prospect did scare Mo’min he knew such things never really happened. Someone’s father always knew someone else’s father, phone calls were made, things got straightened out. Still, he told no one. The weeks passed.

In May, Mo’min went to a friend’s birthday party in Al Misseilah. When his mother came to pick him up, it was clear she’d been crying. She did this sometimes, but not very often. It was something he’d simply taken as her way of being in the world. Less than pain or regret or the simple homesickness she only talked about indirectly every once in a while — going off unprompted about how artificial a place this was, how if the oil ever ran out it’d be a ghost town within a week — he associated it with boredom. He had no idea what his mother did with her days.

They drove home in silence. Just before they reached the compound, she turned at the lights and pulled into the parking lot of the Pizza Hut strip mall. They sat there a while, watching the young men drive in circles, yelling their phone numbers at the passing women. Occasionally a Land Cruiser drove by, its windows open, speakers blasting, the plastic covers still wrapped around the seats, as was the style.

Finally his mother said something had happened. That morning, the Sheikh whose sponsorship allowed Mo’min’s family to remain in the country had called Mo’min’s father and said his work permit had been revoked. There was no recourse, no process of appeal, and no matter how much Mo’min’s father begged for an explanation, a clue to the infraction he’d committed to earn this punishment, the Sheikh would offer none.

We’re going to have to leave, Mo’min’s mother said, and then she broke down crying again. But the words made no sense to Mo’min. He’d known nowhere else. The Shobra of his father’s youth was no more real than the made-up cities from which all those criminals on America’s Most Wanted came, storybook places all of them. But when his mother regained her composure and drove them home, he entered to find the movers already packing.

In autumn, the Credit Suisse Exhibition featured Lucian Freud. He had no idea who Lucian Freud was but he liked looking at the paintings, late at night after the crowds had dispersed and the gallery belonged to the janitors and the security guards — what his friend Melaku called the after-people. The bodies in the paintings seemed to be trying to shed themselves, break free. He liked paintings in which he could infer suffering.

All in all it was decent employment, given his circumstances. Elsewhere in London a man on the wrong side of forty, his immigration status irreparably illegal, couldn’t hope for much more than a late-night gas station or Tesco’s shift and a bedspread in the space beneath a staircase. But here he was, an agent of culture, cleaning up the floors of one of the finest art galleries in the world. Sometimes when the guards weren’t looking he took pictures of the paintings and sent them back to his relatives in Shobra. Sometimes he made up stories about the painters, the lives they’d lived. Sometimes he said he’d met them personally. No one ever challenged or corrected him.

One day he arrived at work to find a row of black-windowed Mercedes sedans parked illegally outside, and an entire wing of the gallery closed.

Visiting dignitary, Melaku said. A collector too, big big money, make big donation, get private tour.

It had been more than a quarter-century since he’d last seen her, and he had long since stopped thinking about what he’d do if he saw her again. Against the flattening glass of years, his memory of the girl on the swing had become smeared past the point of recognition. It was only an artifact of sensation now, the faintest trace of blood rushing, falsely electric the way all youth is in rearview.

Through a small crack where the grand hall doors failed to meet, beyond the two-man security detail stationed there and the half-dozen more that surrounded her highness in the gallery, Mo’min caught a second glimpse of the Emir’s daughter. She was taller — of course she was, they were only thirteen last time — and smiling, in conversation with the gallery director. She was flagpole-postured now, grown fully into the comfort of her fortressing.

Mo’min pushed his janitor’s cart toward the towering doors. One of the men who guarded them put out his hand.

“Not today, mate.”

But Mo’min didn’t listen. He simply kept moving toward the door, and when the two men stepped in to stop him he rammed the cart into them and tried to carry his momentum through the doors, through the other guards, through the walls on which hung the paintings of old men who sought to escape from their own melting flesh, which as he saw the paintings again now and as if for the first time seeing them thinking, no, it was the flesh trying to escape the men. Through the streets and buildings, the sea and the sea. Through time.

He felt himself lifted. The marble floor came up to greet him and all the air left his lungs. He felt the oddest lightness. Even when the other guards, alerted, came running and pinned him further against the floor, the weight of them was nothing, less than nothing. The floor wrapped itself around him and through a phalanx of limbs he caught sight of her a last time and she was home.