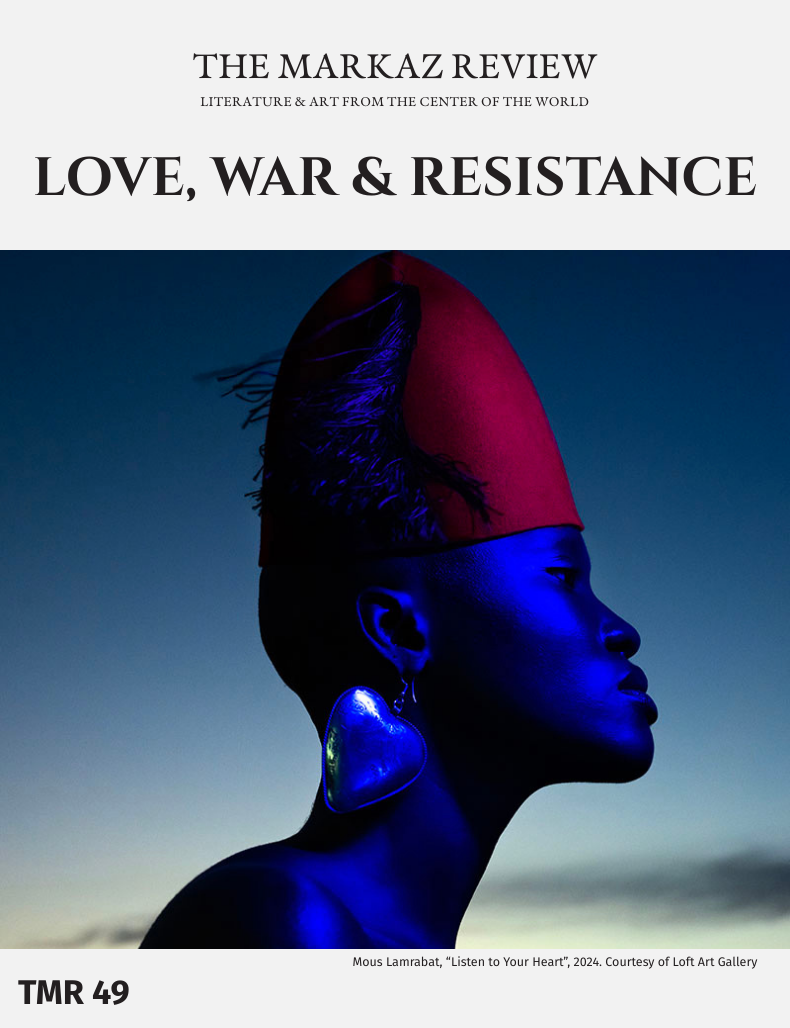

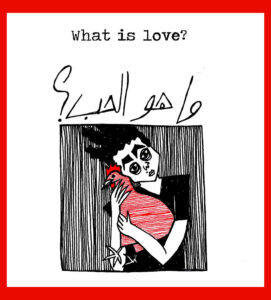

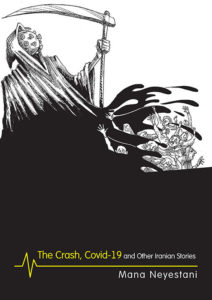

From blindfolding potential dates to threatening them with cockroaches, Iranian YouTube dating game shows go viral and the regime takes action.

“The men seem dumb. The women are smarter or better able to talk about their lives and emotions.” So said an Iranian friend of mine, in his fifties. He had joined millions of Iranians at home and abroad in a guilty pleasure, watching YouTube Persian dating shows and listening to Iranian Millennials, and Gens Z and X reveal their feelings about themselves and the opposite sex in ways that would have been unthinkable for those who witnessed the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Shows in Farsi, “Blind Date,” “Speed Date,” “Gear Date,” “Disc Date,” “Swap Date,” “Love Meter,” and others that take their name from Persian proverbs, like “See the Mother, Marry the Daughter,” or from Western dating apps, “Iranian Tinder,” are all produced at breakneck speed, with multiple episodes uploaded weekly onto YouTube. The phenomenon represents a virtual alternative universe, divorced from tightly monitored and constrained Iranian streets, yet accessible at the click of a button in the privacy of one’s own home. That was until last week, on February 24, when the long arm of the government summoned, arrested, and warned 15 producers, presenters, and makers of online dating programs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTnaRYV2iGU

The Iranian “Blind Date” shows, some lasting nearly an hour or longer, are not as glitzy or highly produced as the eponymous romantic game programs once broadcast on mainstream UK or US television channels. Nor are they as grandiose as those currently being organized as large-scale staged events by the South Korean government to promote marriage and counter the country’s falling birthrate. Persian contestants aren’t featured on big stages or in television studios. They seemingly appear in someone’s living room. The format is relatively straightforward. A man and woman, strangers to each other, sit side by side on separate padded chairs. Usually the two speak directly to camera. Only rarely do they glance over or address the member of the opposite sex beside them.

On the Roo.Line channel’s popular “Speed Date” on YouTube, prospective couples face each other, with a buzzer on the table between them. Whoever first hits the buzzer flashing red to signal rejection or green for approval gets to play another round, opposite a new contestant. In the episodes I watched there is more kicking out than prolonged romantic involvement, which probably makes for more dramatic viewing. Roo.Line’s avuncular presenter and producer Vay Vihad keeps the contestants talking with interjections and hijinks, so that they eventually reveal their “daily routine” and what’s important to them.

In another of Vihad’s programs, “Swap Date,” two men sit on either side of a blindfolded woman in her twenties. The three joke with each other, or get on each other’s nerves, depending. In the end, the young woman says she likes one of the men. Then she admits that she likes the other man as well, thereby crossing one of the Iranian government’s “red lines.” A woman can’t be involved with two men at the same time. In the land of polygamy, that’s not considered proper, or Islamic.

“Blind Date” couples appear less spicy than those on “Speed Date,” and they often display the awkwardness of two people meeting each other for the first time. There is a certain politeness in the conversations. In Iran, revealing or irreverent conversations between the sexes, whether virtually or in real life, are logistically difficult but not impossible. Except for the underground parties that the Gist-e reshod or morality police fail to break up, it’s still frowned upon for the young and unmarried to socialize in state-gaze of heavily CCTV surveillance that takes place in the streets of Tehran. Forget about stealing a kiss — an activity that might still provoke disapproval from conservative or religious passersby. Or at the very least a whack from a stick, or worse, arrest by a chador covered policewoman.

However, while most encounters on “Blind Date” don’t veer into speaking directly about sex, some presenters like Shahab Sadeqghi ask questions rarely acknowledged in public. “What do you do to make a woman happy during her period,” he has asked one of his male contestants.

To the women, he can be equally probing. In Iran, men pay a mehrieh, a cash inducement in Persian Sharia marriages that will be paid to a wife, if a man seeks a divorce. In recent years the increasing price of a mehrieh has meant that men, who have left their wives and are unable to pay, have been arrested and imprisoned, a law being reconsidered by the Iranian parliament. Sadeqghi has asked women “Blind Date” contestants if they believe a mehrieh is a condition of marriage. Sometimes they waive their right to it.

Confidence in love

The Roo.Line channel on YouTube started three months before the September 16, 2022 death of Jina Mahsa Amini and the nationwide protests that followed. A media watcher inside the country told me, “It took time. Many of the program-makers were unprofessional, and they had to learn how to make shows that attracted audiences. After the protests, people became braver and developed new and different ways to present the romantic views of their generation.”

The popularity of “Blind Date” is the result of a new social confidence, particularly in women. Professor of gender studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Cosse Dr. Sona Kazemi explained to BBC Persia’s social media reporter Fare Taghizadeh that the shows “serve as a statement of presence — similar to feminist publications that declare, ‘I exist, and this is the world I envision for myself.’ The way they dress and the way they speak is a reflection of this mindset. We see young women holding balloons,” adds Dr. Kazemi, “ready to pop them if they don’t like a man. And they do it — easily and assertively — saying ‘no’ without hesitation.”

Unwittingly, Roo.Line’s presenter Vahid revealed the mocking dark heart of “Speed Date,” during which a contestant, a mild-mannered jeweler had rejected a woman with large, unnaturally protruding lips, and a face like a mask. (He in turn had been rejected by a young woman with pink hair who described herself as “naughty” and was replaced by a baker). Suddenly at the end of the program the audience is privy to behind-the-scenes footage. There’s background noise and everyone’s a little giddy, even Vahid. He admits to the jeweler (and the still watching audience) that nobody had expected to be visited by a plang, or leopard — Persian slang for a woman with extensive plastic surgery.

Roo.Line (“roo” in Persian meaning “on,” hence the “online” channel) has many permutations on a theme, all presented by Vahid, sometimes wearing sunglasses. In “Gear Date,” another of Roo.Line’s dating programs on YouTube, contestants are given their own gearshift to push — left for green, right for red. Since 2022, the channel has posted 270 videos on its channel. With over 61.5 thousand subscribers, the channel has received over 19 million views. Perhaps more than any erosion of religious or conservative values, the sheer proliferation of the online dating shows is yet another indication of Iran’s ailing economy. New episodes, posted sometimes twice or three times a week, guaranteed Vahid and the Roo.Line an income from YouTube ads, in a country where US sanctions have placed a living wage beyond the reach of ordinary people.

Unquenchable love

The personalities of the presenters are key to a successful dating show. On TrendeFarsi, two teenage girls talk to Amir Imani. The snarky teenage boy has written on the YouTube profile his reasons for doing the shows — “first: to make people happy”; “second: to make money from YouTube”; and “third: to improve my English.” A frequently used come-on line he repeats to young women he records and videos over Zoom is whether their eyes are “real or fake.”

When the teenage girls insist that they aren’t wearing contact lenses, he then suggests he knows a way he can possess their beautiful eyes i.e. when they bear his children — an odd proposition to hear from someone so young. He makes a 180-degree turn when he asks another of his women interviewees to sidle up to her computer screen. He takes in an exaggerated breath, says he can smell her “perfume,” and then suddenly declares that she stinks. The teenage girl’s initial reaction is one of outrage, followed by an expletive in English that needs no translation from the Persian.

TrendeFarsi can also be watched on TikTok. The dating show offers not so much “a glimpse into the lives of participants as they navigate the ups and downs of modern romance,” as promised by the website Persianyoutubers.com that lists the best 2024 Iranian dating shows. At best it’s cheap, queasy entertainment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pAyD5prKCPY

A more considerate, empathetic presenter is forty-year-old Shahab Sadeqghi, who describes himself on Instagram as “musician, performer and composer.” He has an official license to play music from the Iranian government and performs in a metal band. His contestants, whether on “Blind Date” or its spin-off “Ex Date” are not teenagers but in their late 20s and 30s. On “Ex Date,” separating or soon to be divorced partners answer his questions and speak to camera about themselves and their ill-fated relationships. Much has been written about the high educational levels attained by Iranian women, less so about how a religious patriarchal society such as Iran puts pressure on young men, to provide, no matter their country’s economic circumstances.

In this introduction to this episode of “Ex Date,” Sadeqghi describes acting as the go-between for a married couple who are divorcing, as “the biggest challenge of his career.” Erfan is a rapper, actor and singer — from his Rapcrow Instagram profile that conveniently pops up for the viewer he has a following of 67.5 thousand people. His artist wife Arti also works in theatre. The two in their twenties created and produced a rap musical that flopped. When Erfan confesses his feelings of failure — artistically and economically — Sadeqghi doesn’t hesitate to draw lessons from his own life.

“At 27, I was constantly studying at various universities, hoping for a better future. But I didn’t achieve what I had envisioned, so I changed my path and entered the world of music. I worked hard for years, and now at 40, I don’t feel behind or ahead of anyone. Two years ago, I started from zero on YouTube, earning nothing at first …” he says.

On another episode of “Ex Date,” the couple under scrutiny expresses love for each other, but still decides to break up. Sadeqghi consoles them, “The sense of responsibility I have seen from you in the past few hours is truly valuable. Love does not come easily. You must appreciate it.”

Love bites

Not all Ex Dates are drawn from real life experience. Relative newcomer to the Iranian dating scene, Ba Reza started making his “Ex Date” programs last year. In one from last year, early twenty-something Negin introduced herself as a materialistic young woman, who pursued a relationship with Omran because he had money. She said she left when he stopped spending on her.

The backlash of over 6,000 comments from viewers must have stunned Negin. Months later, she shows up on another YouTube video, this time being driven around an unspecified Iranian town by Majid MC, who describes himself on YouTube as “I post prank, hidden camera and funny videos …” He’s a comfortable interviewer in his car.

Majid MC explains how Negin’s family has been affected by Ba Reza’s “Ex Date” before she slowly starts to speak for herself. She tells Majid MC’s car camera that Mr. Reza had given her a script to read, and she had gone along with it, for “the exposure.” In the international ecosystem of social media even Persians yearn to be famous. While over 30,000 viewers saw Ba Reza’s original episode with Negin as a gold digger, only 11,000 viewed her retraction.

As opposed to the kind of online therapy offered by the understanding musician Shahab Sadeqghi, break up shows are a popular form of entertainment. Ashi Ley is another prominent Iranian dating show presenter and producer. On his programs he also features men and women between the ages of 20 and 30 who, once in a relationship, have since separated. On YouTube, both parties describe their partner’s negative and positive traits. In one episode, Zeinab and Alireza come together to share their feelings having been separated for many months. Ley asks Alireza how he’d react if he saw Zeinab in the street, holding hands with someone new. To which Alireza replies, “I would burn them both.” His jealousy proves to Zeinab that her ex still cares and she should reconsider their split.

Ley’s other spin-off program, Love & Hate, takes romance to another level. His Persian contestants perform competitive stunts that once took place on quirky Japanese and American game shows of the 1990s, but haven’t been seen before in Iran. These YouTube videos come with a warning, in English and Farsi: “Please do not try these challenges at home. All these challenges have been performed with full safety precautions in a completely safe environment.”

In one video, a tied-up man, unable to move, must free himself quickly or his partner will be covered in snakes or cockroaches. Who said love is painless? Or as the Persian poet Hafez warns in the first Ghazal of his Diwan, from the 14th century: “ … love seemed easy at first, but then came difficulties …”

Killing love

When fans go to the Instagram pages belonging to Ashi Ley and Roo.Line they find waiting for them a message from the Public Security Police or Faraja (Polis-e Amniat-e Omumi-ye Faraja). Faraja is the Iranian agency responsible for internal security and public order, and its emblem or logo, shaped like a law enforcement badge, features two CCTV cameras, with the words: “Due to the publication of criminal content contrary to public morality and decency the page was taken down, in coordination with the judiciary.” Still Ashi Ley’s and channel Roo.Line’s dating programs can be found on YouTube.

According to Tasnim News Agency, the semi-official news outlet associated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the government took action “due to the increasing prevalence of the phenomenon of blind dates (anonymous dates) in cyberspace and numerous complaints from families about the[ir] social, cultural and moral harm …” The head of the Public Security Police of Faraja, Majid Feyz-Jafari has vowed: “The crackdown” on the online dating shows “will continue until cyberspace is completely cleared of such content.”

Weeks before celebrity vblogger and host of “Blind Date” VinyViz was censured by the authorities, he gave a lecture on internet marketing at Tehran’s National Library and the Archives of the Islamic Republic. Later, his “Event,” filmed against a backdrop of heavy YouTube product placement featured some of the best-known darlings of Iranian social media. (Their Instagram profiles, complete with followers’ statistics, popped up as they came out onto a makeshift catwalk.) This is the second time in ten months the authorities cancelled VinyVidz’s Instagram page and suspended his activities. But months later he surfaced again, created a new Instagram page for himself and his 1.2 m followers who joined him there, and uploaded new shows on YouTube. The government’s approach to popular influencers is chaotic.

Another victim of the government clampdown was Ashkan Shadkami, who started making dating videos last year. More a comedian behind a desk than a presenter courting contestants, he uses split screens, video clips, still photographs, and candid camera footage to provide a fast-paced, running commentary on his generation. He covers everything from old-fashioned wedding dresses brides wear to men’s hair falling out. After the government ban, his latest YouTube video has enjoyed more than 22 million views. As Iranian journalist in Istanbul Masoud Kazemi told Iran International TV, more people had watched one of Shadkami’s videos than the audience figures for all of the programs on Iranian Broadcasting Corporation, the official TV of the Iranian state. He went on to say: the closures of Instagram pages were meant to distract from the bigger story of the country’s failing economy.

Three years ago, the government launched its own dating apps, aimed at creating a more suitable environment in which young women and men could meet and marry according to Islamic principles. In an effort to modernize, only days before Faraja targeted the online dating shows, the government issued official licenses to 205 “matchmaking” centers and websites.

“It facilitates the process for those genuinely seeking a permanent marriage,” stressed Iran’s Deputy Minister for Youth Affairs at the Ministry of Sports and Youth Alireza Rahimi. “The expansion of cyberspace is an opportunity that should be utilized. If any issues arise, we are responsible. Law enforcement and cyber police must prevent unauthorized matchmaking websites from operating, while ensuring that the legal ones function properly.”

Only time will tell if this heavily regulated, old-fashioned worldview of modern romance will appeal to the young at heart on the Persian online dating shows and the mass audiences watching them.

Raha Nik-Andish contributed additional reporting and provided translation from the Persian to the English, for this story.