A teacher from Japan travels to Afghanistan to teach at a girl's school.

Japan, March 1986

Katrina walks into her mother’s room. She trips over the wire of the electric heater that her mother had placed right in front of her, startling the older woman. Katrina shows her the passport. According to the document she will be 27 years old next month. She sits next to her mother and points out the logo and stamp of the Afghanistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“They have issued me with a visa. I can go, dear mother.”

Her mother looks away.

Katrina puts the passport on her knee and stares at the painting of white cherry blossoms in front of her.

She pleads slowly, “I want to go. It is my heartfelt desire to go on this trip, mother.”

She looks into her mother’s eyes, her own black eyes emanating kindness and hope.

Her mother takes her daughter’s cold hands in her own. She removes the blue crystal necklace that she is wearing and puts it around Katrina’s thin, delicate neck. The silver chain, warm from her mother, heats her skin. Touching the necklace hanging from her neck, Katrina smiles.

Kabul, April 1986

The wind is blowing. Carrying a backpack, Katrina walks alongside women who have shoulder-length hair and legs bare from the knee down. As she passes through the crowd, she looks for her name. A man wearing a striped shirt and leather jacket is holding a paging board with her name on it: Katrina Iri. She stands in front of him and smiles. The wind blows her hair from her face, revealing her eyes. The man greets her in Japanese and welcomes her to Kabul.

From the car, Katrina sees the city and realizes that it had rained the night before. She lowers the car window, smells the earth and flowers. She inhales more air into her lungs.

“Have you spoken to the girls from Ashyana school?” asks the man.

“No, I have only contacted the administration.”

“The girls are so excited to see you. Every group has been talking about the new teacher from Japan for days now.”

“I am eager to meet them,” she says with a smile, her eyes fixed on the sun shining through the trees quickly passing by.

She arrives at the building. All eyes are on her as she strolls towards the school office. When she enters, the staff welcome her. The teachers will start their classes ten minutes late today, in honor of her arrival.

Katrina sits on the sofa and drinks tea. The manager gets up from behind the desk, walks to the window, then turns to Katrina and says, “You can take a few days off to get some rest. Your timetable is ready, your teaching hours have been determined and your students are waiting. Ms. Fauzia will guide you to your room.”

“I want to have the timetable and books today.”

“But of course, Ms. Fauzia will provide you with everything. Whenever you want.”

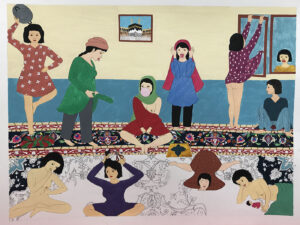

May 1987

Teenage girls of varying ages have been divided into two groups of 11 players and are playing football. The weather is cloudy and rainy. Acacia trees are blooming, their scent in the air. The ball bounces off the playing field. It hits Katrina on the left shoulder, who is standing nearby, dressed in a white blouse. The girls surround her.

“Are you hurt?”

“Are you in pain?”

“Girls, stop the game, did we hit Katrina?”

Katrina smiles and shakes her head, sending everyone back to the football pitch while she goes inside.

In the last two minutes of the match, a goal is scored and the winning team cheers happily. Their celebrations are suddenly drowned out by repeated destructive noises cutting through the air, destroying the peace of the day. From the second floor of the school, Katrina and some girls look out of the window. A missile has struck the acacia tree on the side of the road, while another has landed on the clothing and grocery store. There is fire and smoke. Ambulance sirens can be heard everywhere. The girls watch the scene in silent shock.

Katrina pulls the curtain across the window. “Back to work, everyone.” A deep sadness surges through her heart. The girls go to their rooms.

Alone in her room, Katrina pours water into a bowl. When she opens the window, a few fresh leaves are blown inside, landing on the floor. She looks at the alley, her eyes falling on the green leaves covering the ground. She sits at her desk, lifts her black leather-covered diary from the table and writes:

Missiles fall, rain down —

Kk-kk-boom, kk-kk-kk-boom —

Tearing spring apart

August 1988

It is the turn of the third group to visit Paghman district for a summer holiday. Sitting on a stone in the middle of the river, Katrina’s feet are in the flowing water. She has a camera hung around her neck and is taking pictures of the girls as they stand in the water.

A man and a woman are sitting by the river on a rug they have spread out, waiting for their children to return from their mountain walk. Katrina goes up to them, looking at them thoughtfully as she gets closer. The man with almond eyes and a sparse beard resembles her father who passed away a few years ago, while the woman with green almond eyes and fair skin reminds her of someone, maybe one of her schoolteachers or one of her mother’s friends. With a smile, Katrina asks for permission to join them on the rug.

“May I take a picture of you?”

The man and woman both shrug and smile. With this expression on his face, the almond-eyed man looks even more like her father. Heart-gladdened, Katrina takes their picture as they hold their teacups. She plans to send this photo to her mother to say, “Look, I found my father here.”

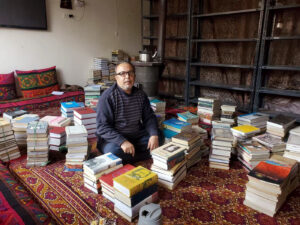

On the other side of the river, the girls ask each other what Katrina really does: Is she a physicist, a mathematician, a football coach, a photographer — or all of them? One girl says Katrina is a writer. She says that when she went to Katrina’s room to talk to her, she was writing something in Japanese. When Katrina saw her curiosity, she translated what she had written.

A girl who has just arrived at Ashyana asks: “What? Katrina speaks Japanese too?”

“Why wouldn’t she? It is her language.”

“Isn’t she an ethnic Hazara?”

“No. She is not a Hazara.”

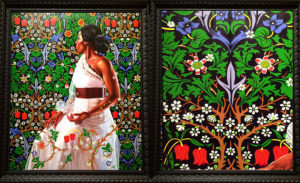

An Ashyana teacher with relatives in Paghman had invited everyone to their family orchard for lunch. Among the fruit trees, three large red, purple and pistachio-colored cloths are hanging on a line, a gentle breeze blowing through them. Katrina realizes that the pieces of cloth are scarves that women use to cover their hair and wrap around their necks.

Everyone is sitting together around the table, eating and talking, but Katrina is lost in the vibrant colors of the scarves.

The hostess, a happy woman, looks at Katrina, nods her head and says, “Her mannerisms do not suggest that she is a foreigner.” She asks her, “Do you like it here?” and Katrina simply smiles. Sometimes no one can understand a person’s heart, not even the one you love.

After the meal, they walk through the orchard. Katrina takes picture after picture until the sun goes behind the mountains. She’d fallen in love with the mountains in Kabul on the very first day she’d arrived and noticed them stretching into the distance as far as her eyes could see.

Later that night, sitting at her desk and looking at the photos, she recalls many memories — of the day, of the people, of that beautiful valley surrounded by high peaks. She wants to share the charm of the place and the affection and innocence of the people. She opens the drawer and picks a photo from among the many she has taken. On the back she inscribes, “This beauty is presented to my mother” and puts it in an envelope to post the next day.

Before she goes to bed, Katrina writes in her diary:

The girls’ laundered scarves

Swaying on the sunlit line

There is peace today

December 1992

From Ashyana, Katrina goes to a school that has now become a refugee shelter. The noise of children crying mingles with the voices of upset men and women talking about being forced to leave their homes and jobs. In the school courtyard, children are following a seven or eight-year-old boy who has a loaf of bread in his hand. A teenage girl walking with sticks changes direction when she sees them.

Katrina approaches a group of women who are sitting around burning coal in a metal container.

She addresses one of them, “Where have you been displaced from?”

Upon hearing her question, they all gather round. The circle grows bigger by the minute as men slowly join too. Everyone shares their plight.

“We came from the village. Our wheat fields were bombed.”

“They shelled our house. We lost everyone.”

“We have nothing left — not even a carpet to sit on this cold ground.”

“We barely escaped with our lives.”

An old man repeats to himself, “My daughter was picking grapes when she was hit by a rocket. She loved grapes … loved them so much …” He slowly moves away from the group gathered around Katrina.

People start to tell others that someone has come to ask us where we’ve come from; someone wants to bring us food and clothes; someone has come to check on us…

In the midst of the crowd and noise, Katrina forgets what she wants to say. She gets up to leave.

“Will you come again?”

“Did you want to know how many of us are in need?”

She hears one woman say, “We’ve had to leave our home in Paghman.” Others loudly repeat the names of the places from which they have been displaced.

A cold wind blows. Katrina passes a man who is cutting a thick tree with an axe. The tree, the man, the cold and the displacements invade her heart and mind.

At Ashyana, she sees the girls watching her from the second floor window. She goes up and sits next to them. They are using cardboard boxes as fuel, burning them in the stove. The radiator is not working, it is now just a hanger for coats and scarves.

Katrina opens the envelope from her mother. Her mother says that she will be sending the money Katrina requested in two days. She writes in her diary:

O Paghman’s spring breeze!

Pass by those empty, still homes,

For I can’t go there.

The girls wonder what she has written. She translates the characters for them.

July 1994

Katrina had heard on the radio the night before that there would be a three-day ceasefire. The next morning she goes to the kitchen, where there is no cook anymore, to see what food they have. The cupboards are empty. There are few pots. The containers that were always full of flour, rice, beans, and peas now only echo eerily. The cooking oil container doesn’t even have a drop of oil inside.

With a note in her hand from Ashyana, she goes to the shop. There is nothing left in the nearest one. The next store is also empty. She reaches a shop that has the materials she needs, but she has now traveled very far from the school. She waits for the seller to finish serving the woman wearing a burqa who is buying oil.

Noise suddenly fills the air. Katrina looks outside. She leaves the store. Missiles are flying in the sky like bullets. She searches for somewhere to take refuge, but where? She is facing cut trees and a long road ahead. The air is filled with the sharp, sour smell of gunpowder.

She moves forward. A rocket lands where she had been standing a moment earlier. A wave of sound and fire knocks Katrina down to the ground. Her head hits a concrete electric pole and cracks open. Blood starts flowing through her black hair onto the pavement on the side of the road. Her beige woolen coat is riddled with holes. When they lift her off the ground, they realize that the back of her coat is burnt too.

Katrina breathes her last under the Kabul sky amid pain, darkness and the sound of rockets. The small, connected links of her silver necklace are covered with a layer of blood; the blue crystal pendant grows colder with each passing moment.

Two hours later, a white ambulance arrives with sirens blaring. It takes away the wounded and the dead. Katrina’s eyes are closed. At the hospital, the doctor examines her and sends her to the morgue.

The hospital is full of people looking for their loved ones, the smell of blood and medicine filling their noses. A man and a woman are looking for their daughter. At the morgue, they scream and hug Katrina’s body and cry, “It’s our little girl; our daughter herself. She is our sweet daughter.”

The man and the woman receive Katrina’s body in a white shroud. The mother cries, alongside the relatives who have joined them, and two women read the Quran over her dead body until morning.

The next day, at two hours past noon, they take her to the graveyard. They bury her on the slopes of Kartah-ye Sakhi hill under the sun and place a red flag on her grave so that everyone can tell that a martyr lies there. The woman pulls her green scarf over her eyes and starts crying. She grabs the freshly dug soil and cries.

After he is done at the graveyard, the father visits the place where Katrina’s blood was spilled. He painstakingly digs the hard and solid tile cemented to the ground and hoists a red and green flag there. He piles stones around the flag so that it does not move in the wind and rain. It is to ensure that everyone knows where the pure blood of a martyr was spilled so they do not step on it.

Katrina’s black leather-covered diary remains in Ashyana. The last entry reads:

A dove’s love blossoms,

It wakes me up every dawn,

If it is not crushed.

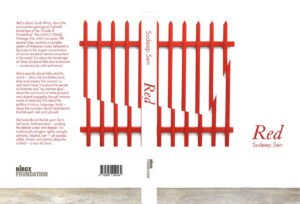

“Kabul’s Haikus” by Maryam Mahjoba was developed through the Paranda Network, a global initiative from Untold Narratives and KFW Stiftung, which connects and amplifies voices of writers from Afghanistan and the diaspora.