Deborah Lindsey Williams

Writing in the early part of the 19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that in the newly founded America, “there does not exist . . . any class in which the penchant for intellectual pleasures is transmitted with comfort [or] … holds the works of the intellect in honor. Thus the will to engage in these works is lacking as much as is the power.”

It is a nudge to the United States’ history of insularity that one of the most compelling studies of the national character (even taking into account his obliviousness to gender and race) comes from a young visiting Frenchman deeply versed in the teachings of European philosophy. Two centuries later, his comments still resonate.

De Tocqueville’s observations remind me that the US has, almost from its inception, been suspicious of “intellect”; his comments also remind me, surprisingly, of my college students, who claim to like the classes I teach in literature and writing — but always want to know how, exactly, these classes are going to help them get jobs. All that open-ended discussion is fine but it’s not practical, they say. Almost to a person, these students see their college careers as a kind of tick-box exercise: the undergraduate degree as a stepping stone to some well-paying job.

In their belief that college equals job, students have flocked in greater and greater numbers to the so-called STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math) or business programs; the humanities have become niceties, a flourish they can point to that makes them “well-rounded,” but lacks any real market value.

Now, granted, the problems confounding higher education — in the US and elsewhere — are multiple, intricate, and interrelated, but one aspect of this problem is that teachers of the humanities have not done a good job explaining why these subjects matter; we have ceded the town square of public opinion to those who insist that professors (other than those who teach “practical things” like economics, business studies, or STEM) are intellectuals, a word that has come to mean out-of-touch, overbearing, unwilling or unable to function “in the real world.”

What we seem to have now, instead of public intellectuals, in the deep sense of that phrase, are influencers, as Moustafa Bayoumi writes, and pundits, those talking heads who populate TV news shows or fill the editorial pages of newspapers. The word pundit comes from Sanskrit and means “knowledge owner,” which seems just about right: a pundit pontificates, demonstrates the knowledge that he owns, while an intellectual is about knowledge production.

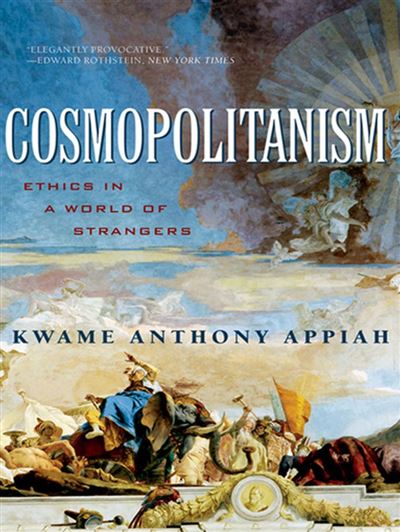

In order to produce knowledge, however, I have to ask questions, explore, be curious enough about something to try and find out more about it. Kwame Appiah, in his book Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, talks about the importance of conversation — such a low-tech, low-stakes engagement — as a way to make ourselves known to each other. A true public intellectual embodies this engagement; the verb of an intellectual is ask. Pundits pronounce, influencers sell.

The irony, of course, is that we need a culture of questioning and curiosity in order to push back against the sludgy tide of authoritarianism that seems to be on the rise in societies around the world. Asking questions is antithetical to fundamentalists of all stripes, which is why, of course, one of the first thing any fundamentalist government tries to do is rid itself of artists and intellectuals. Perhaps that’s how I will start answering those students who want to know why they should bother with humanities classes: No big deal, I’ll say. These are just the classes where you’ll find the weapons and power to fight against tyranny.

A lovely piece!

Williams is on the money….so to speak