A photographer of social realism goes to the end of the Earth and finds herself.

Text and photographs by Tamineh Monzavi

As a student studying photography in the mid-2000s, I was taking photographs of what was happening on the streets of Iran. This had more significance to me than the curriculum I was being taught in university, which showed students how to photograph nature and flowers.

Early on I knew that I would not gain much from the rigid, university photography program, which only provided standard answers to already formulated questions. My focus was on the still unanswered.

I wanted to become a photographer who documented social issues, not just someone who knew how to work a camera properly. The limited opportunities for female photographers in Iran and the male dominated environment of my country concerned me greatly.

For three years I worked on my first project, The Brides of Mokhber al-Dowleh. The series not only shaped my practice, it became my most influential body of work.

I was fascinated by the fact that men sewed the majority of bridal dresses in Iran. The male environment of these bridal workshops created the most feminine dresses. The ethos, combined with the background noises of an old radio, the young dressmaking boys’ laughter and the sound of a man’s scissors cutting the silk, were surreal.

Simultaneously I was working on another project. In 2008, I had been assigned by a magazine to photograph male drug addicts in the rundown, rough neighborhoods of south Tehran. My research led me to a shelter in Grape Garden Alley. The shelter housed homeless women from all over the world.

Most of them, too, were drug addicts. Through the efforts of private charitable organizations, these women were kept off the streets and given food, medicine, housing and clothing. It was heartwarming and encouraging to hear stories of women who had managed to quit their addiction and find a safe haven in society.

I spent three years in Grape Garden Alley, and continued off and on until 2016 because of a fascinating person I met there.

Tina was transgender. She had left home at the age of fifteen because her family would not accept her sexual identity. Unwelcomed in her own family and society at large, for many years she lived a delusional reality shaped by drugs.

Her arrest and subsequent two years in jail not only ended her addiction, it was the motivation she needed to restart her life. The small community in the shelter was the first place she called home after so many years of struggle.

At the age of 44, she was living independently in a room with her dog, waiting for brighter days to come. Unfortunately those days never materialized. In early 2020, she died at the age of 50.

In 2012, during a highly sensitive and depressive political climate in Iran, I was arrested. A month in prison and the trauma following my arrest and incarceration suspended my photographic practice for two years.

The effect of such a long gap made me lose my nerve as a documentary photographer. Still looking for a comfort zone, for a while I would stage shoots and photograph them.

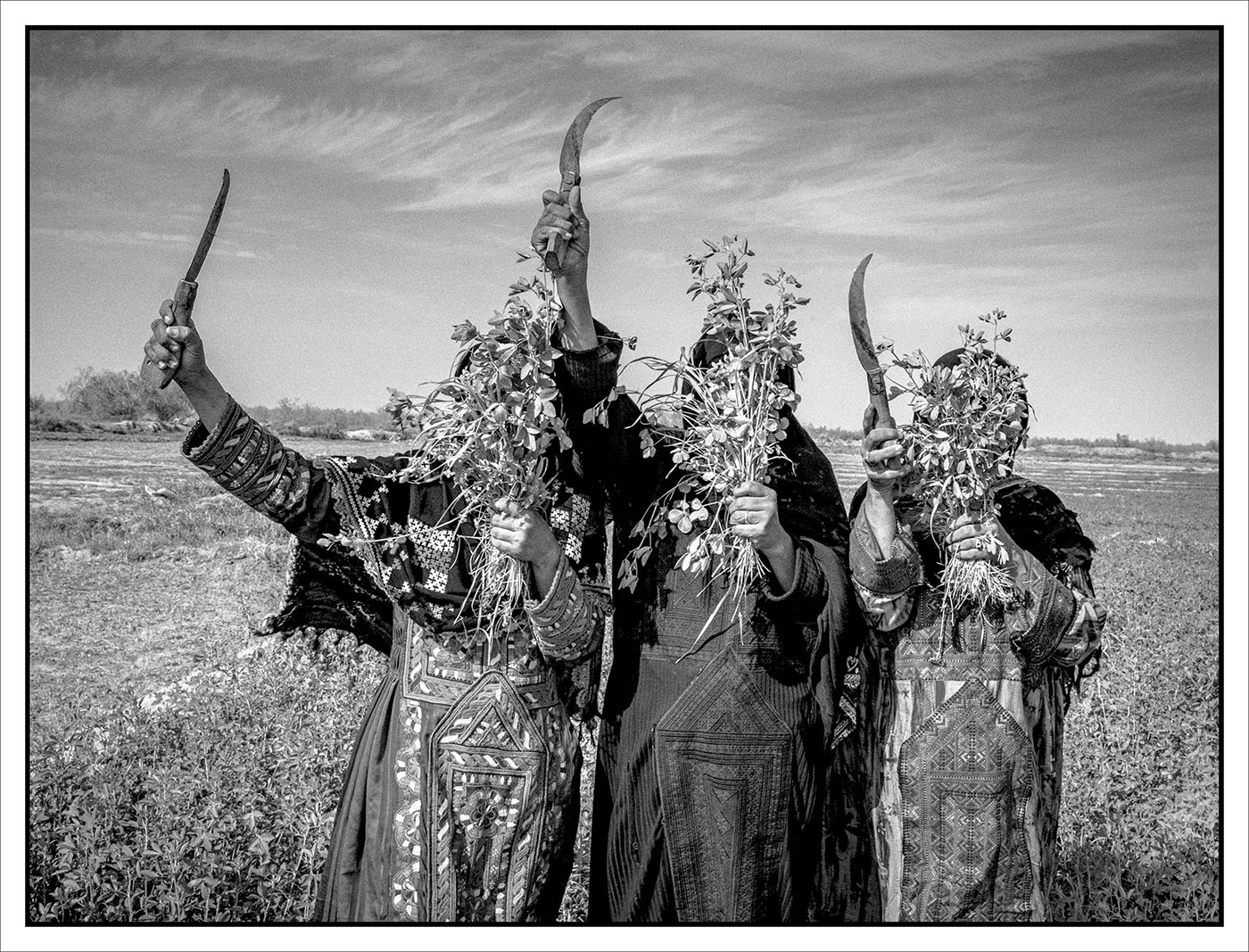

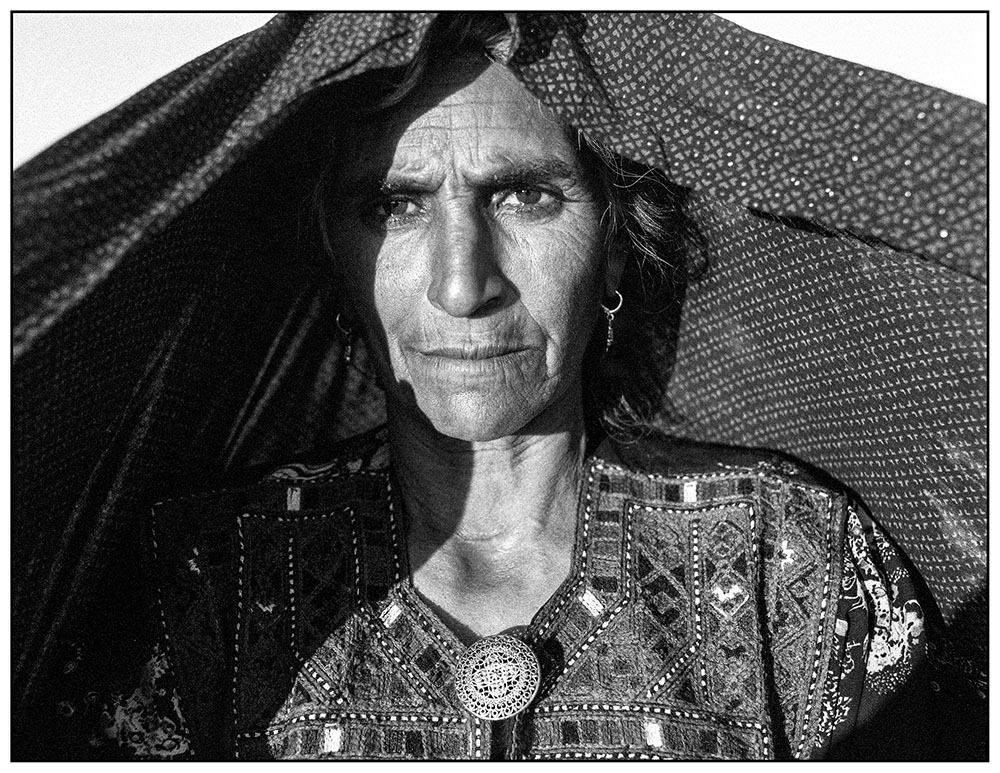

Then between 2019 and 2022 my interest, passion and experience were ignited by the everyday lives of Iranians in different parts of the country. This work concentrated on the roles of women in urban and rural settings, especially in the coastal provinces of the Persian Gulf, including Sistan and Baluchistan.

I focused on various aspects of life in an African Iranian community. The people, known as the zangis, had been forcibly brought to Iran by Arab slave traders before the 19th century, from southeast Africa, the modern-day countries of Tanzania and Mozambique. On Iran’s southern coast, the zangis adopted the area’s language, accent, and religion. Until half a century ago, the oldest members of their community still remembered how they first arrived there, stories that have been forgotten by subsequent generations. What has not been forgotten, however, are the cultural mementos their families carried with them from Africa, which still have a major impact on the culture of Iran’s southern coastal region. Women too play a prominent role in their ceremonies.

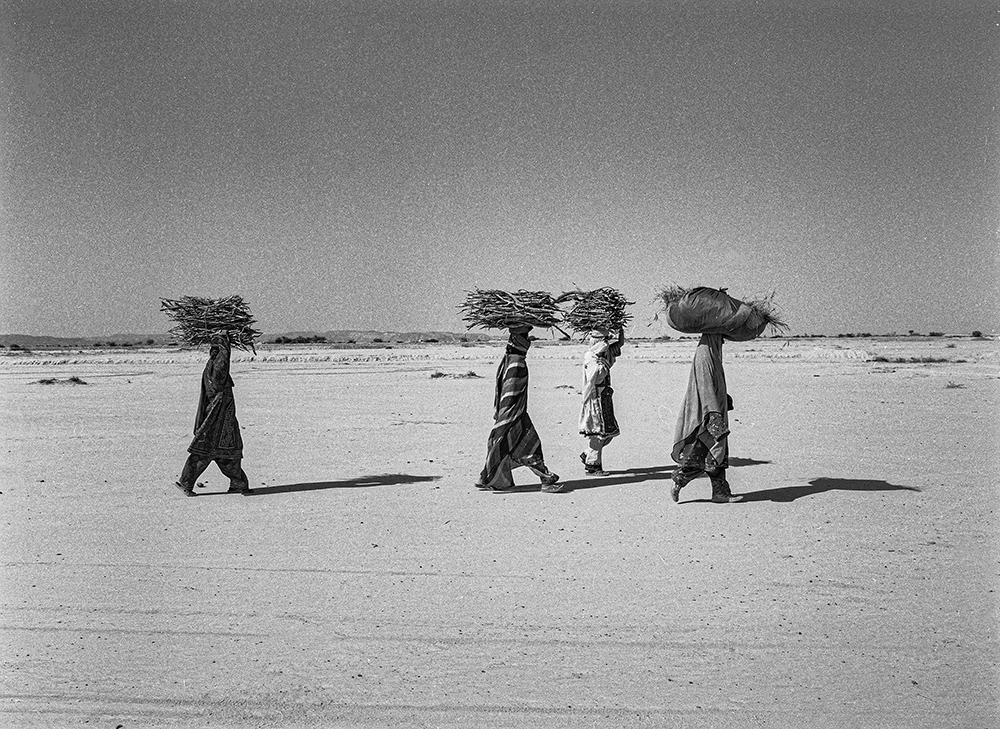

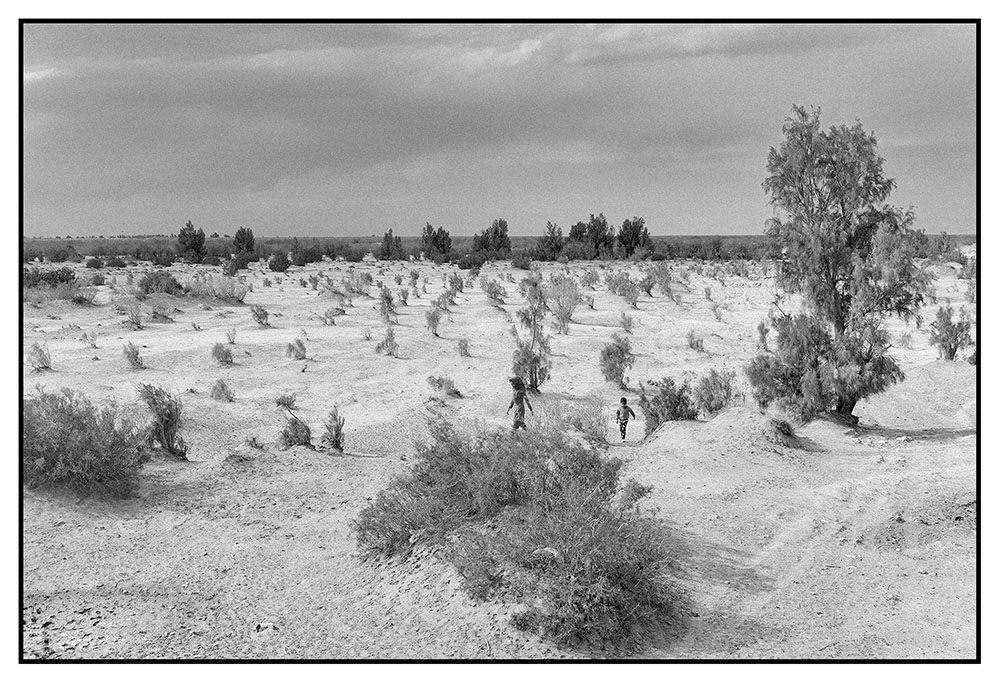

I had also started the series, A Life in front of You, about Lake Hamoun, aka the Hamoun Oasis, a seasonal lake and wetlands located in the Sistan and Baluchistan province. Once Iran’s second largest fresh water lake, in the last couple of decades it has become nearly dry all year round. A large part of the population that once depended on water from the lake has been forced to flee to cities near and far.

During my time there, Lake Hamoun and its environs experienced one of its most severe dry spells. These had begun in the early 1950s, when the construction of a dam on the Helmand River in Afghanistan prevented snowmelt from the Hindu Kush from reaching the lake and wetlands. Water diversions and drought came to a head in 1998 when animals and crops died, and the fisheries closed. Nearly 100 towns were buried in sandstorms.

The nomadic inhabitants of the region usually live close to the water. However, because the condition of the lake many have been forced to move. Those who stayed have faced great challenges, caused by of the lack of resources on which they depend for their survival. For three years I lived among them and studied their oral traditions.

In the middle of the lake, a basalt lava shaped like a trapezoid, Khajeh Mount, was home to fire temples and castles during the Ashkanid (247 BC-224 AD) and Sassanid (224-651 AD) empires. The Zoroastrians considered the lake holy; it was the place where the saoshyant (promised savior) would be reborn.

When I first started working, nature photography reminded me too much of my Tehran University-approved syllabus. But like a lot of people around the world, my relationship to nature changed during Covid, when all of us contended with a seismic shift in our lifestyles. The most challenging years of my career were 2020–2022.

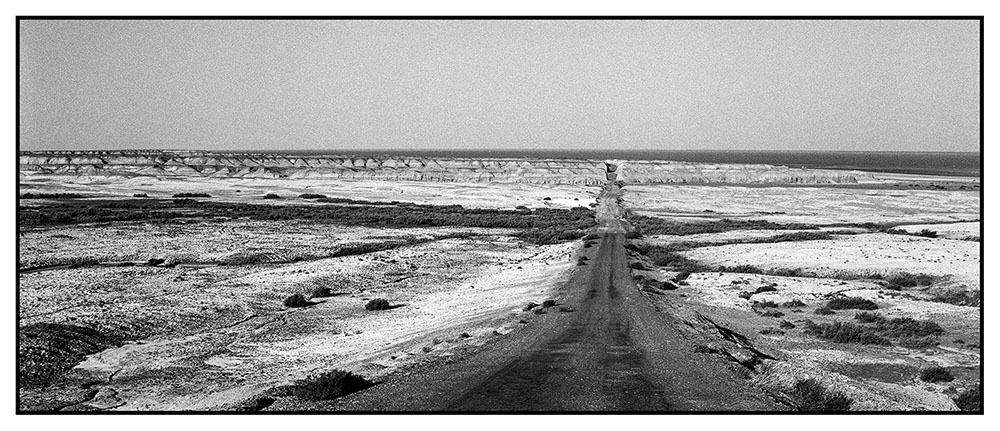

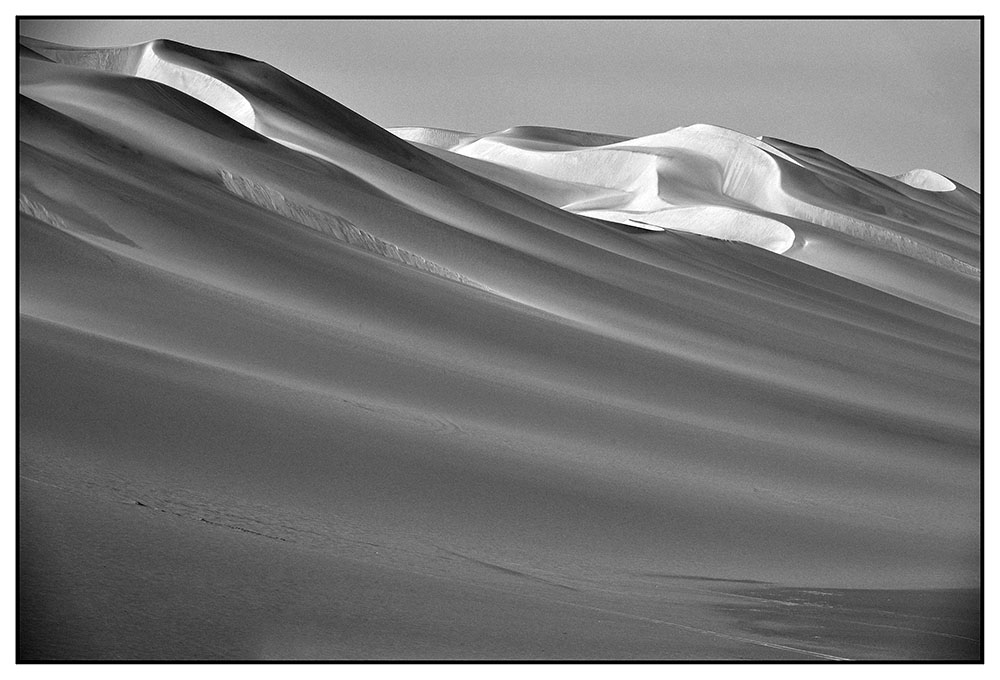

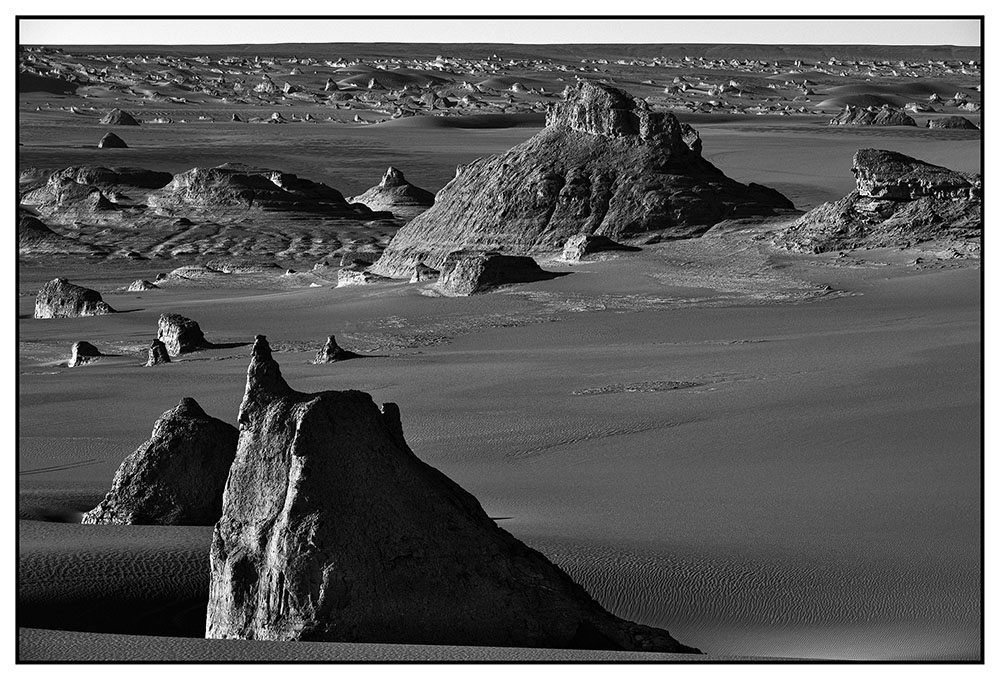

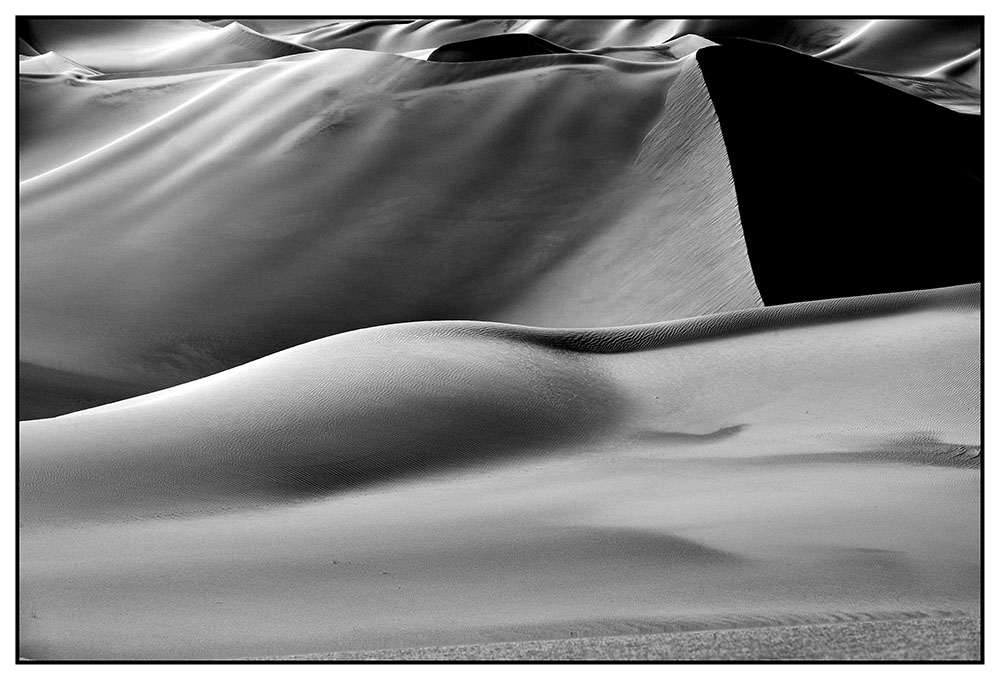

I felt the urge to escape from humanity. My next project took me to place uninhabited by humans. The Lut Desert or Dasht-e-Lut or “empty plain” in Persian is 20,000 square miles of sand and fantastical rock formations in southeastern Iran. In 2005, according to NASA’s satellite data of land surface temperature, the Lut recorded the hottest temperature on the surface of the earth, 70.7°C Celsius (159.26° F).

Its sand dunes, ergs, mega-yardangs (kaluts or “sandy mountains” in Persian), desert pavements, and immense, salty soil flatlands reminded me of the shape of a woman’s body and the body of the earth. Through my eyes, I touched a symphony of images. The Lut was where I found solace.

Before this I had never taken photographs of nature and landscapes. However, this project enabled me add new perspective and meaning to my work. It gave me a deeper understanding of my own determination and motivations.

This essay was adapted from an illustrated talk Tahmineh Monzavi gave at Photo London, for the panel discussion: “Our Land: Tahmineh Monzavi, Babak Kazemi and Pargol E. Naloo share their work rooted in their home country,” moderated by Vali Mahlouji, Somerset House, London, 10 May 2023.