Jordan Elgrably

This is not so much a review as an appreciation. My chosen title suggests that few could fail to benefit from the humanization of the “other”? Do you remember the last time you saw a movie or read a book and identified with a protagonist ostensibly very different from yourself? Escaping from the narrow prism of your own consciousness, you became utterly empathic, imagining that the challenges and hardships faced by that protagonist were your own. You became that person. Empathy at this level stretches the spirit; it also is a practical antidote for depression, because getting outside yourself, you feel larger than your ego. You realize that you are not your feelings, but something much greater.

Having made this observation, isn’t it unfortunate that Jews and Arabs (to choose only one conflicted relationship) are taught to distrust each other? Nowhere is this more the case than in Israel and Palestine, where Arabs consider the Jews a settler colony that has confiscated what used to be Palestine, and where Israelis learn from an early age that Arabs are enemies of the state.

But Jews in the United States also learn to be wary of Arabs. This was true long before 9/11 and is the result of stereotypical characterizations of Arabs as terrorists proliferated in film, television and news media. It may also be true that American Arabs consider Jews to be members of a privileged class of people in the U.S., due to their prominence in multiple fields. They also cannot help but remark America’s unwavering support for Israel (thanks in no small part to the lobbying of AIPAC).

This mutual distrust has only been exacerbated by our wars in the Middle East, our treacherous friendships with Saudi Arabia and Israel (both countries have spied on us and killed Americans), and the anti-Muslim rhetoric that became common currency during Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

You can see how easy it is to become entrenched in a narrow view of the world by identifying strongly with one’s own people. That is why any experience that allows you to expand your consciousness and step outside that purview is an opportunity not to be missed. And that is why I recommend that you read The Return.

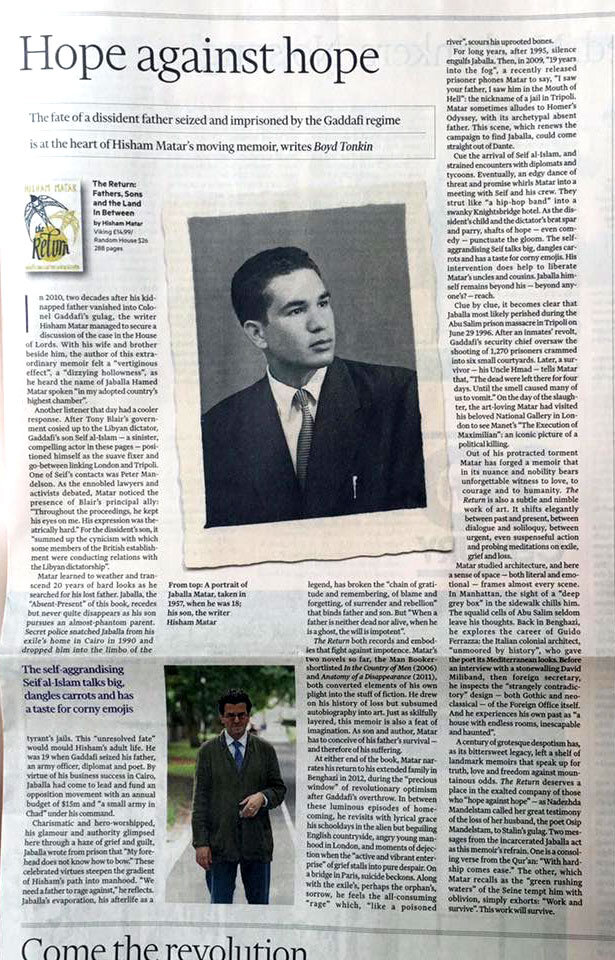

The international Libyan novelist, Hisham Matar, published this memoir about his return to Libya after the 2011 revolution, more than 10 years after his father Jaballa was disappeared by Qadaffi’s henchmen. I call Matar “international” because although he was born in New York while his father was a diplomat there, he has also lived many years of his life in Cairo and London. Despite the success of his novels and other publications in English (translated into many other languages besides), he still thinks of himself as an exile, and it’s unclear whether he will ever feel completely at home anywhere he goes.

The Return has nothing to do with Israel and Palestine, and indeed, makes no comment on the Arab-Jewish rift. The book is at once very political as it condemns despotic regimes in Libya and Egypt for example, but also apolitical in that it is entirely taken up with a son’s love for his father, and his search to discover the truth about his demise. Hisham Matar’s narrative is that of a thoughtful young man, a writer, who ruminates on the nature of his relationships with his mother, father, brother Zaid and his many relatives, some of whom he tries to liberate from Qaddafi’s hellish prison, Abu Salim.

At the end of the day, The Return‘s greatest accomplishment is that it humanizes its author and his family, and all those Libyans opposed to Qaddafi’s brutal dictatorship (with some examination of Egypt’s responsibility for Matar’s father’s disappearance). It follows the underdog as he struggles against the oppression and indeed the terrorism of the state. It is my contention that having read this book, you will become at the very least more aware of the ways in which Arab lives resemble your own, and (one can only hope), more empathic in the process.

The Return very much leaves you with the feeling that we are all of us in this world together, and we must strive to defend human rights and call for enlightenment wherever we find darkness.