Iason Athanasiadis

Clouds masked a wintry sun whose brooding illumination of Istanbul for a few hours each day added an otherworldly patina to walking its streets. In Samatya, one of the ancient city’s oldest and most historical districts, the main street provided a constantly alternating sightline of cross-topped steeples and domes. But very few of the minorities by whom they were built remain.

On the weekends, Istanbul, the Mediterranean megalopolis of 16 million inhabitants wrapped by waterways, appeared an abandoned city. It was December 2020 and the authorities had just reinforced the nightly movement restriction with a full weekend lockdown. Tourists were exempted to encourage them to keep on coming and, for the lucky few already there, that decision instantly transformed one of the world’s most walkable but congested historical cities into a captivatingly anachronistic stage-set.

On a cobbled street a few meters from the Marmara seashore, Taki, a man in his late 50s and one of the last inhabitants of the area’s Greek-speaking Rum Orthodox community, hung perilously out of the window of his peeling wooden house, looking the worse for wear on his third straight day of drinking. He had recently lost his mother, with whom he lived, and was uttering incoherent sounds, possibly of grief, possibly of anger. His neighbors, longtime internal migrants from outside Istanbul who ran a fish tavern at the bottom of an adjoining wood building, greeted his utterances with indulgent smiles.

“Taki’s always doing this,” one said. “He goes on these benders but we’re here to keep an eye on him.”

A little further down, a belltower peeked over walls coiled with barbed wire. A Rum lady local to the district who now looked after the church, opened its metal outer door but refused to accept visitors without a permit from the Patriarchate.

Inside the nearby Ayii Theodori church, four priests commemorated the Metropolitan of Vlanga’s nameday to a church almost empty aside from two silent women towards the back and a fifth priest sitting up straight in the front pew. Vlanga is a district on the shore of the Sea of Marmara historically inhabited by the Rum community, whose name embodies their lineage, reaching back to the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium. Along with Kontoskali (Kumkapi) and Psomathia (Samatya), they complete Istanbul’s historical seaside triptych, and include the burned, pillaged and earthquake-struck ruins of some of the city’s most important Byzantine palaces and monasteries.

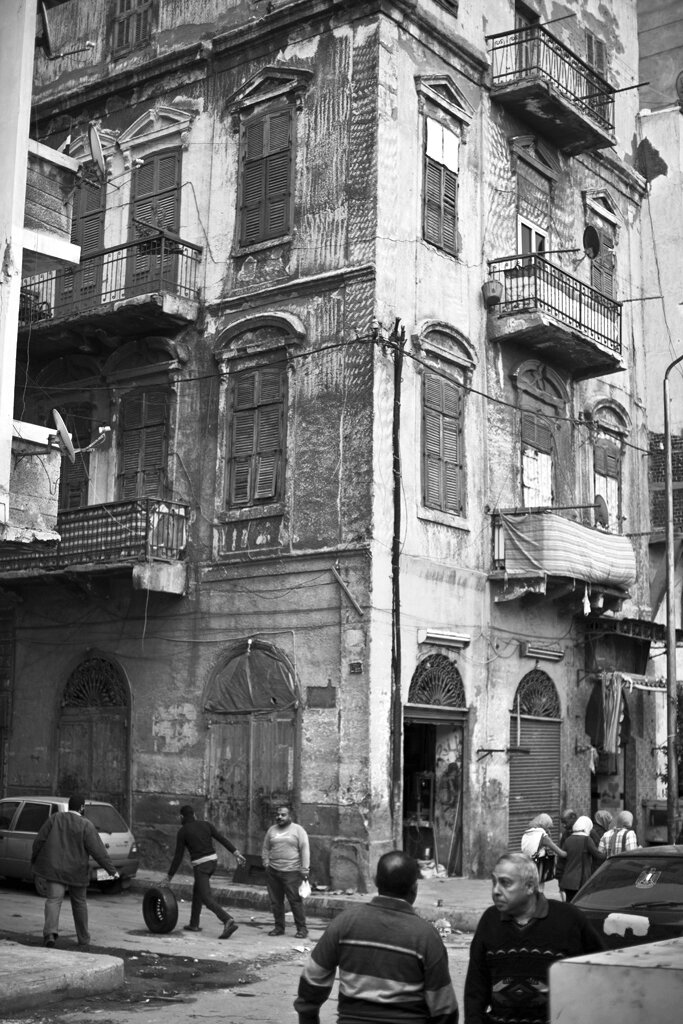

Although the city was deserted, the neighborhood around the church pulsed with street-sellers and Arabs, Africans and Asians who preferred the area for its low rents and proximity to the wholesale districts of Aksaray and Laleli. Some were just resting for a few months or years before continuing onto Europe; others were slowly putting down roots, enrolling their children in the remaining Rum school and — for the Egyptian Copts and Ethiopians among them — injecting new life into the area’s vacant Greek and Armenian churches.

Less than 1,500 Rum and about 50,000 Armenians are left in Istanbul, but they no longer reside in these historical districts, which most Istanbullus also shun. The new patchwork of migrants and refugees infuses fresh life, but the way in which their multiculturalism differs from the old cosmopolitanism reflects all the changed circumstances between a 19th century Mediterranean where empires were breaking up into nation-states, and a contemporary sea suffering the passing of the nation-state in the era of globalization and climate chaos.

Achieving amnesia

In 2014, as the Islamic State amassed in lawless regions of Syria, Iraq and Libya, I lamented the regional moment in The Cities We Lost, an essay examining how the nation-states that emerged during the 19th and 20th century “fashioned us in such a way as to define ourselves according to narrow ethnic and religious definitions, or against common foes, rather than visualising us as richly-textured components of one harmonious regional historic tapestry.” But the intervening years proved that ripping up the nation’s legacy presupposes overcoming instilled behavioral patterns. Not unlike nationalism, the Islamic State harnessed religious feeling in order to create a sense of chauvinistic superiority among its followers. In doing so, it furthered a cultural isolationism that was the logical continuation of nationalism’s fragmenting narrative.

“Not unlike nationalism, the Islamic State harnessed religious feeling in order to create a sense of chauvinistic superiority among its followers. In doing so, it furthered a cultural isolationism that was the logical continuation of nationalism’s fragmenting narrative.”

The countries founded after the collapse of the Ottoman, British and French empires knew that their survival was invested in forming in their subjects’ minds (be these “Turkish”, “Egyptian”, “Greek” or “Israeli”) a distorted patriotism intended to dispel generations of accumulated memories of coexistence. To get to that point, the multilingualism, cross-cultural communication skills and communal bonds that developed over centuries among residents of cosmopolitan communities in Smyrna, Aleppo, Sarajevo or Diyarbakir had to be degraded to convince them they needed the protection of the nation-state.

Whether the Ottoman millets of the Rum, Armenians and Jews in what became Turkey, the Muslims of the Balkans, or the Jews of North Africa, there were three stages to instrumentalizing these communities. Firstly they were reduced to social outsiders against whom the “indigenes” could sharpen their antagonism. Then, their eventual departure rendered them absentees unable to defend their histories against distortion by the reductionist narrative of the resulting nation-state. The minorities who remained became loyal Others, their community representatives regularly trotted out by the new administration to publicly underline their allegiance. Eventually, they were absorbed by their host societies, while the descendants of those who emigrated to the newly-constituted ethnic homelands retained only a tenuous link through infrequent visits.

Once the humans had been dealt with, it was time for their physical and historical traces to be obscured. Some of Istanbul’s most important Byzantine monuments were reused as spolia in other constructions, or wrecked in 1870 as part of the orgy of destruction involved in connecting Istanbul to the European rail network. This was a key station in the city’s coming-into-modernity, involving both the first groups of mass tourists arriving on the Orient Express, and the line’s extension under the ambitious Berlin-to-Baghdad railway line, a geopolitical object of Great Power rivalry that developed into one of the causes for World War One (and also marked a historical first when the train was used to enable genocide during the 1915 elimination of the Armenian populations). Today, the physical remnants of Constantinople, Istanbul’s most resonant predecessor, are either converted into museums, mosques or decompose on the periphery of car washes, parking garages, and under the highways and train lines of this post-Ottoman city adapted to the age of locomotion.

In North Africa, ancient Jewish communities in Cairo, Alexandria, Tripoli, Tunis, Oran and other cities became associated with the Israeli state after its founding in 1948. Following their ejection, or in the aftermath of successive wars between Arab states and Israel, their synagogues and secular buildings remained locked. Yet another elucidatory cultural link that could challenge the relentless state narrative was removed. The silence deepened.

In Libya’s Nafusa mountains, the indigenous Amazigh community dealt with successive waves of invaders by folding their animist beliefs into the dominant religion, be it Judaism, Christianity or Islam. But decades of censoring their cultural and historical narrative resulted in an amnesia whereby, when I encountered a Star of David etched in the rubble of a half-collapsed religious building in 2013, no local could answer what it represented and how it had ended up there.

Mediterranean, A Cultural Landscape is now a classic.

Mediterranean, A Cultural Landscape is now a classic.

Removing or muting the minorities was the most efficient way of achieving amnesia as to a remarkably recent and functional past. Many of the minorities were no less immune to the narratives propounded by the nation-states claiming to represent them (Greece, Turkey and Israel) and willingly removed themselves from the mixed communities where they had lived for centuries, relocating to new imagined homelands. Others stayed true to the pull of their roots, or were skeptical of their new homelands’ economic viability, and had to be convinced to leave through other incentives, such as pogroms, nationalizing their businesses, social engineering or bilateral state agreements (for example the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey). In the case of Egypt’s Jewish community, it was so integrated in Egyptian society that Israel organized a covert action, the notorious Lavon Affair, to intimidate them into departing. The same appears to have happened in Baghdad, a few years earlier. In Greece, Muslim and non-Muslim ethnic minorities were subjected to decades of social and state pressure, including burying their villages in military zones for which special visitor passes were needed.

The only place on the Mediterranean where multiconfessionalism remained largely intact, despite similarly seguing into a nation-state after a period of French colonial rule, was Syria. Although the religious minorities supported the Alawite-dominated regime during the recent civil war and were protected by it, “these (successor) regimes ended up by almost inadvertently obliterating the cosmopolitan values and economic prosperity they inherited from their local bourgeois and Levantine predecessors while failing to replace them with more equitable and representative principles of national belonging,” historian George Haddad assessed in Revolutions and Military Rule in the Middle East.

Sixty years later, ISIS formed in the Arab World as a Sunni Muslim transnational reaction to the nation-state’s depredations, but using some of the same divisory methods. One of its main stated aims was to demolish the postcolonial borders defining the new states and revive the Caliphate, but it appeared to suffer a failure of imagination along the way and set about recreating, in the cities it captured, structures remarkably similar to the states it was supposed to replace. ISIS was the fundamentalist sibling to the Arab Spring’s more secular uprisings, but both failed, not least because they were shaped by exclusivist “myths congealed into mythology, history into historicism,” as Predrag Matvejevic noted in his Mediterranean: A Cultural Landscape. The nation-states outlasted them, demonstrating that they had managed to bore down deep into the psyches of generations of their citizens, depriving them of an alternative vision.

Remains of the day

In mid-December in Istanbul, the Orthodox Patriarch paid a visit to St Demetrios Sevastianos, a 19th century church rebuilt on an ancient ayazma (sacred spring) a few metres from the Gate of Adrianople, the point in the defensive walls where Mehmed the Conqueror is said to have entered the city in 1453. The church, which is called akritiki (marginal) for no longer having any faithful, is looked after by a family of ethnic Arab Christians from Antioch, a province of Syria ceded by France to Turkey through a rigged referendum on the eve of World War Two, in exchange for not entering on Nazi Germany’s side.

“As the minorities departed their cities of birth, they left behind an emerging landscape of dysfunctional and corrupt post-colonial governments beholden to national and international interests, which hobbled private initiative and perpetuated weak educational systems. Critical thinking was discouraged for fear of challenging national narratives that were often paper-thin. ”

One of the two sons, Sezgin, almost apologetically explained that he was the first of his family to be given a Turkish name and said that they had trouble being accepted by the local Rum community when they first moved to Istanbul because of their Arab heritage. This was at a time when the Rum had shrunk to almost zero and there were no longer enough children left to ensure that the Arabic-speaking newcomers would learn Greek well enough to achieve integration.

Sezgin proudly showed us the church’s freshly-repaved courtyard. The renovation seemed poignant given how, for decades now, the church remains silent all but once a year. I thought a little about inter-community relations, lost opportunities, imagined resentments, and lose-lose dynamics, all backdropped by a hostile state. The Rum community had once been wealthy and powerful but was now reduced to empty buildings’ dulled gleam, absent descendants, and a failure to mine history for lessons. A little bit like nationalism.

From Alexandria ascendant to Mediterranean brain-drain

“For these reasons, and others yet to be sorted out, modernity hesitated to drop anchor in the ports — east, west, north and south — of the Mediterranean,” Matvejevic concludes stoically. The circumnavigation of Africa and the discovery of America had already stripped the Mediterranean of its status as global trade’s primary sea, although the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 returned some of its lost volume, jump-starting Alexandria’s ascent.

But by the 1900s, as the world piled into industrial modernity, the Levantines, Italians, Greeks, shuwwam, Jews and other Mediterranean movers and shakers followed global capital to London, New York, Hong Kong, Cape Town or to wherever else it bifurcated. Many of them had built connections from their business dealings with colonial authorities that they would further monetize in their new domiciles. The former owner of the luxury Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul, Prodromos Bodossakis-Athanasiadis (no relation to the author), became one of Greece’s top industrialists off the back of the connections he developed in his hotel lobby.

As the minorities departed their cities of birth, they left behind an emerging landscape of dysfunctional and corrupt post-colonial governments beholden to national and international interests, which hobbled private initiative and perpetuated weak educational systems. Critical thinking was discouraged for fear of challenging national narratives that were often paper-thin.

The cosmopolitan port cities saw their status downgraded, and soon played second fiddle to the new country’s capital. Thessaloniki took a backseat to Athens, as did Smyrna and Istanbul to Ankara, and Alexandria to Cairo. The port cities often evoked humiliating memories for the nationalists, who associated them with being treated as servants on their own land by foreign business elites. Nor did they welcome reminders of recent pasts that were multicultural and nuanced. It cannot be accidental that the only cosmopolitan city to make the transition was Beirut, the capital of the only state to be founded for a religious minority, the Maronite Christians of Syria.

“What was Salonica, once the outlet for a vast hinterland of thousands of kilometers, destined to become, with the restrictions of boundaries reaching down to its very doors?” asked Leon Sciaky, a member of Thessaloniki’s Ottoman Jewish Diaspora in his Farewell to Salonica, writing shortly after the Greek Army claimed his birthplace in 1912. “There was talk of making a free city of it, a kind of modern Venice serving as the warehouse and emporium for all the Balkan states. But such a project, still nebulous, required a cooperation and good will we felt was far from the reality.”

Sciaky was right to doubt, and he soon followed his instinct to New York, never to return. Standing on the boat sailing to America, he “saw the tall minarets, the domed Byzantine churches, the red roofs and ancient ramparts recede more and more, until nothing remained of my native city but a faint white blur against the darkening hills. Long after darkness had swallowed this last vision I stood there, leaning against the guardrail, conscious even then that my early world had died.”

Two years after the Greek Army took Thessaloniki, the First World War conflagrated in the unstable post-Ottoman Balkans. It was both a consequence of industrial modernity and its testing ground. In 1917, a fire burned most of Thessaloniki down. In 1922, Turkish troops defeated the invading Greek army and another fire ravaged Smyrna. These fires, and the conflicts that swirled around them, marked the end of Mediterranean cosmopolitanism and launched a century of nation-state orthodoxy.

Today, state mismanagement has fuelled an eloquent brain-drain across the sea that binds and divides. The children and grandchildren of the minority and diasporic communities of yesteryear express their apathy over being brought up ill-equipped for modernity in memory-elliptic homelands by voting with their feet and departing for better economies. Although attached to where they grew up, they will not return as long as corruption, invented traditions and narratives of racial purity thrive.

As the refugee crisis highlights issues of racism in Mediterranean states, the sclerotic and seemingly unreformable educational systems that shaped the departees prove perfectly inappropriate for bringing up the generation now called to welcome and integrate those fleeing war, climate change and dead-end futures. How can someone brought up on the myth that their ethnicity and religion render them superior to their newly-estranged neighbours learn to welcome strangers and live alongside them on an equal footing? This persistent narrative of racial or religious superiority underlines the systematic discriminatory acts practiced by states and people across the Mediterranean, from abusing domestics in Lebanon to an official policy of pushbacks by the Greek coastguard on the Aegean, the beatings of migrants by Turkish nationalists and Libya’s notorious slave-camps. Perhaps recalling our recent cosmopolitanism can provide us with a toolbox that allows us to overcome what is one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century.

Excellent article, Jason, I would like to read it again and again, there is so much information, so many layers of history that contributed to this loss of cosmopolitanism.