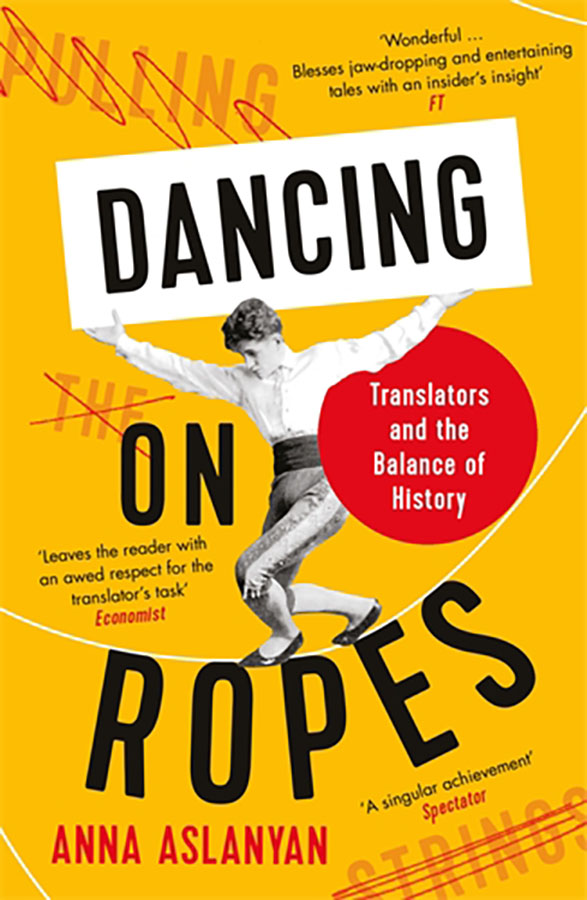

Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History, by Anna Aslanyan

Profile Books 2022

ISBN 9781788162630

Deborah Kapchan

One might think that there is nothing left to say about translation. A perennial subject, it is in fact what facilitates cosmopolitanism — an understanding of the aesthetics, ethics and politics of peoples and cultures unlike our own through the translation of their written and oral works. I have read and taught a majority of books about translation in my graduate classes for years — from Walter Benjamin to Jacques Derrida, Paul Ricoeur and George Steiner, to say nothing of the important work of Lawrence Venuti. So it was with hesitation that I agreed to review yet another book on translation. What is there yet to say?

As with all works, whether fiction or nonfiction, it is the storytelling that changes everything. Anna Aslanyan’s book, Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History, carves out a unique voice, as she examines translation in its social contexts, particularly the performance of interpretation. It is a thoroughly engaging and illuminating read.

Aslanyan begins with an anecdote about a crucial moment in history, when Japan was given the ultimatum to surrender in WWII. The translators of Japan’s response, which employed the verb mokusatsu, “to kill with silence,” needed to be circumspect. And indeed, it was translated variously in different quarters. The Japanese minister said his intention was to say “no comment,” but instead the American press translated it as “to treat with silent contempt.” “The fate of Hiroshima was sealed,” says Aslanyan. Translation has not only aesthetic but political consequences. This is one of the take-aways of the book: the import of translation in history.

Historians are quite right to point out that the tragedy wasn’t caused by translation difficulties alone. Yet debates around the translator’s role, as old as the profession itself, always revolve around the question of their agency. In our multilingual world the balance of history, unstable as it is at the best of times, hinges on different interpretations of words. Some translators believe themselves to be a mere conduit, ideally an invisible filter through which meaning flows; others argue that it’s far less straightforward: in the end, they use their own words, accents and inflections, and so they inevitably influence things. Can translators take liberties? Should they? The nature of the job, as we are about to see, means that interventions are hard to avoid. (pp. 1-2)

Aslanyan, who grew up in Moscow and lives in London, has experienced this firsthand, as she is not just a literary translator, but has also been an interpreter, a job that requires as much fast diplomacy as it does linguistic skills.

Translation and the philosophy of interpretation are never far apart. Indeed, Aslanyan reviews some of the main and most interesting points in her introduction: that concepts, and not words, are what must be translated; that perception may very well be different in other languages, and thus percepts and concepts are both hard nuts to crack. (Here, without saying it explicitly, she invokes a softer version of the Sapir-Whorf thesis, which states that language determines perception.) Multi-linguals are thus of necessity multi-perceptuals, and, one may posit, can relativize experience with more finesse. But whether interpreters smooth over difficulties or exacerbate them depends on the context, and Aslanyan gives us several rollicking examples in the pages of her book.

Aslanyan departs from usual treatises on translation, by plunging into the stories of those who practice the craft, those who “make it intelligible while preserving both the letter and the spirit; to get at its meaning; to make it work.” Hers is more a pragmatic journey than a philosophical one. She is concerned with how to dance on ropes. The metaphor comes from Dryden’s preface to his translation of Ovid, where he compares the translator to a figure with fettered legs, trying to balance between source and translated text while not falling. Elegance is a feat in such an endeavor, though clearly masters can accomplish it. But the falls are as instructive as the expertise, and that is what this book entertainingly demonstrates.

Aslanyan’s stories begin in the Cold War, and particularly with the ripostes, witticisms and proverbs used by Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev. She recounts a moment when Khrushchev took a Russian proverb out of context. Not only did he employ the phrase, “We’ll show you Kuzma’s mother” (translated literally in the US press and so completely incomprehensible initially) but Khrushchev himself used the saying incorrectly, causing a great deal of confusion on both sides of the fence. (If you want to solve the enigma, you’ll have to read the chapter.) Aslanyan continues to explore how the use and misuse of proverbs and idioms in the diplomacy of that era misfired, sometimes hilariously, sometimes with dire consequences. As Aslanyan says, “In these stories of the world at the edge of the abyss, the act of translation itself emerges as a culture clash where infinite variations of meaning are capable of tipping the balance of events. We’ll never know if a catastrophe would have occurred had any of the above communications been translated differently. What’s evident is that the Cold War was fought not just through but also by translators” (p. 21). Her research into the historical role of translation and translators is meticulous and a joy to read.

Aslanyan also recounts the stories of interpreters who must translate jokes of political figures. Berlusconi was a joker, for example, but jokes are often hard to translate. The brilliance of Ivan Melkumjan, his translator to Russian, lay in his ability to change details of the joke so as not to offend the Russians, while still delivering the punchline. And all this on the spot. Melkumjan clearly understood the cultural codes of both the Italians and the Russians, and he catered to the needs and mores of each. “To translate someone well you have to understand not only what they are saying but also why. This applies to jokes (which, as we have seen, don’t have to be rendered literally to produce the desired effect) and serious utterances in equal measure,” Melkumjan tells Aslanyan when she interviews him. “When my client wants to achieve something, I’ll make that my priority. I’ll do my best to help them get there, using my skills, my delivery style…I know a lot of people who just want to translate everything accurately and don’t really care about the rest. I’m not like that: I work towards whatever goal the speaker has in mind. And it appears to pay off” (p. 27). Melkumjan makes it his job to understand the intention behind the sentence as well as the joke, and Aslanyan elucidates his artistry, and that of other interpreters, with humor and wit.

In the rest of the book, Aslanyan goes back in history to tell tales of political emissaries as well as missionaries whose fates were sealed, living or dying according to their abilities to translate their intentions to their captors or to apprehend and perform the physical gestures of the peoples of foreign lands. Here, translation and interpretation are clearly melded with ethnographic skills — observation, interpretation and translation of social perspectives not one’s own.

She also demonstrates the power of a single word to ignite the human imagination and thus to change history. “In August 1877, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli turned his telescope towards Mars,” Aslanyan recounts. And he saw canales. The decision to translate this Italian word as canals and not channels immediately gave rise to speculation about the possibility of life on Mars. Did a civilization build these canals? Aslanyan follows the impact of this one-word choice, through the social imagination it spawned about life on other planets.

Dancing on Ropes is replete with stories about interpreters and wordsmiths in history. We learn about John Florio for example, who, in 1578 published a grammar and phrase book in English and Italian, entitled Firste Fruites. Florio was then hired by the French Embassy, and became a friend and implicit defender of Giordano Bruno, who was nonetheless soon burned at the stake for his “heretical” (scientific) ideas. Florio published a dictionary in 1598, the century that saw the publication of the first bilingual dictionaries. He also became the translator of his contemporary, Montaigne. In The Essayes, Florio’s own style is evident and the English translation was highly appreciated by Shakespeare. How a “simple” translator had the power and influence he possessed is one of the lessons of this book.

There are many stories of famous translators like Florio — dragomans, they were called in the Ottoman Empire (from turjuman, “translator” in Arabic). These tales are like fabulae themselves, full of adventure, intrigue, spying and word play. The dragomans often softened the words of their patrons, adding polite and even obsequious phrases in the translation that were often not there in the original. They were called upon to be diplomats, as they veered between worlds that they knew but their protectors did not. Still, they were rarely appreciated for the artists that they were.

In these pages we learn about the role of translation in the trial of King George IV against his wife for causes of adultery, a story which also highlights the exigencies of translating gestures and expressions. We learn about Dollman, Mussolini’s interpreter in WWII, as well as Gross, who simply chose not to translate Franco’s words of devotion to Hitler, and thus, Aslanyan implies, did a service to history.

We learn about the scandals caused by Burton’s translation of the Thousand and One Nights. We are apprised of Jorge Luis Borge’s ideas about translation as well as his close, almost collaborative relationship to his translator. Aslanyan also brings us back to the patron saint Jerome, who first translated the Bible.

Aslanyan ends where we find ourselves now: in the era of algorithms and computerized translations. Will the machine replace the translator in the end? In fact, the evidence presented in Aslanyan’s book makes the case that this is impossible. She concludes that “…as long as people continue joking and swearing, praising and ironising, uttering and writing things they mean or not; while human communication still involves all of the above and much else, we can safely say, paraphrasing Twain, that the reports of the translator’s death have been greatly exaggerated.”

Since there is no way around ambiguity, we still need humans (and not computers) to discern the meaning in its social context.

In Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History, Aslanyan sometimes performs dizzying jumps between historical periods. She herself dances on the ropes of time, from the Cold War back to early Christianity, through the Renaissance and forward to modern Argentina. In this plethora of carefully researched stories, she writes with finesse about the impact of translation in the longue durée. Dancing on Ropes is a valuable resource for educators and translators, and a highly entertaining read for everyone interested in the vagaries of history.