On Sunday October 20, the Instants Vidéo festival in Marseille welcomed the Biennale d'art vidéo palestinienne en exil. It was an opportunity for five Palestinian artists, from Jerusalem, the West Bank or survivors of the hell of Gaza, to meet and reflect on their role, as the genocidal war continues in Palestine.

The mildness of one Sunday in October drove many Marseillais towards the sea or the hills surrounding the city. A hundred or so people, however, decided to spend this sunny afternoon at the Friche la Belle-de-Mai, the former tobacco factory that has become one of Marseille’s central cultural venues. Passing under the Module, a sort of concrete spaceship on stilts, we reach the Seita room, in front of which a few people are chatting over coffee. “Today it’s impossible to dissociate oneself from politics: everything is political, what we eat, where we live… An artist who doesn’t take a stand is in itself a political act,” says a young woman. “That’s your point of view, but some artists simply don’t want to say anything about the society around them,” reacts a man in his fifties. “For me, my very existence is political,” retorts his interlocutor, clearly incredulous.

The tone is set: the programming and exchanges at this Biennial of Palestinian Video Art in Exile, hosted at La Friche by Marseille’s Instants Vidéo festival, will be permeated by the question of the place of artists in the world. What can art still say, show and express, after a year of massacres in Palestine?

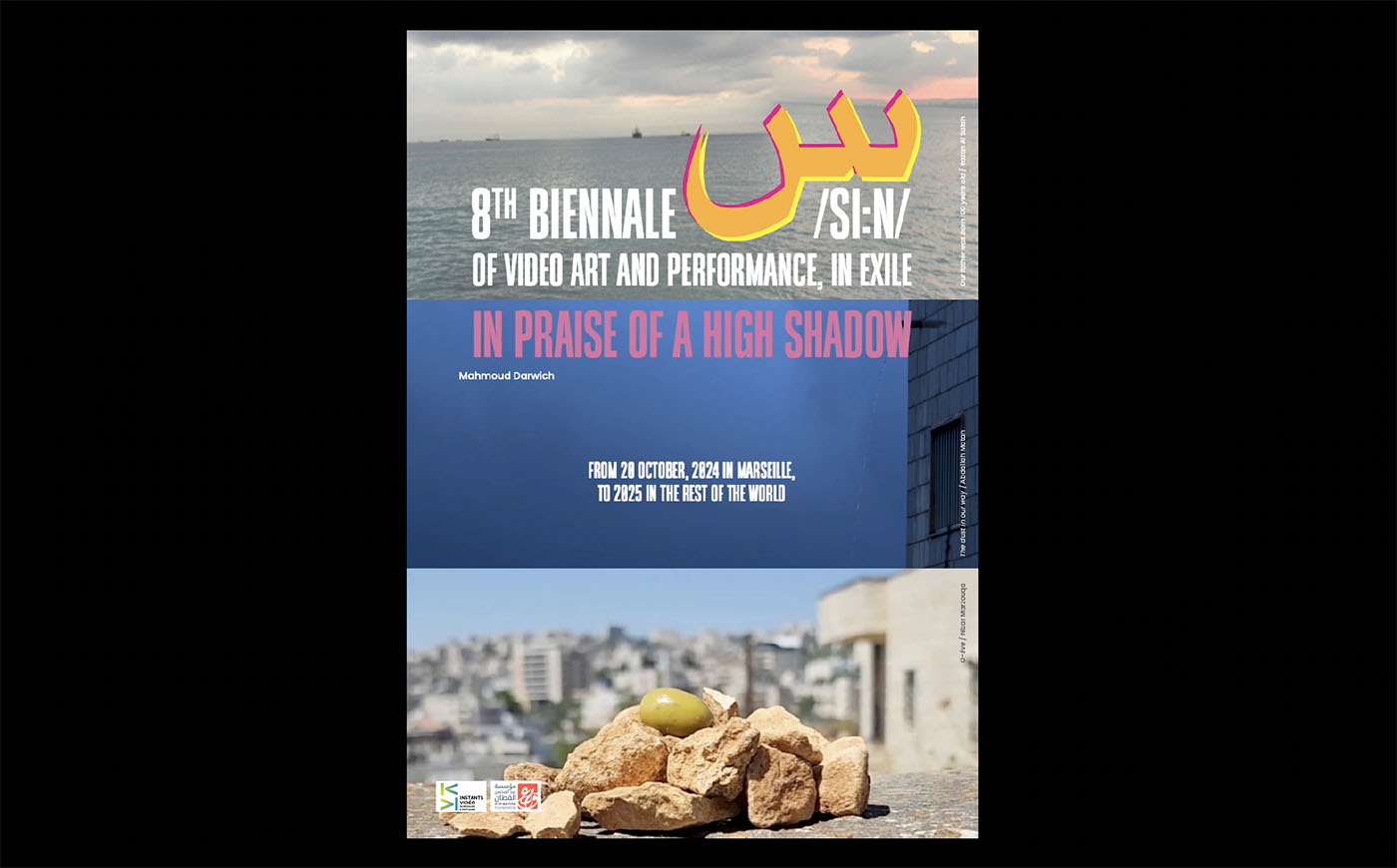

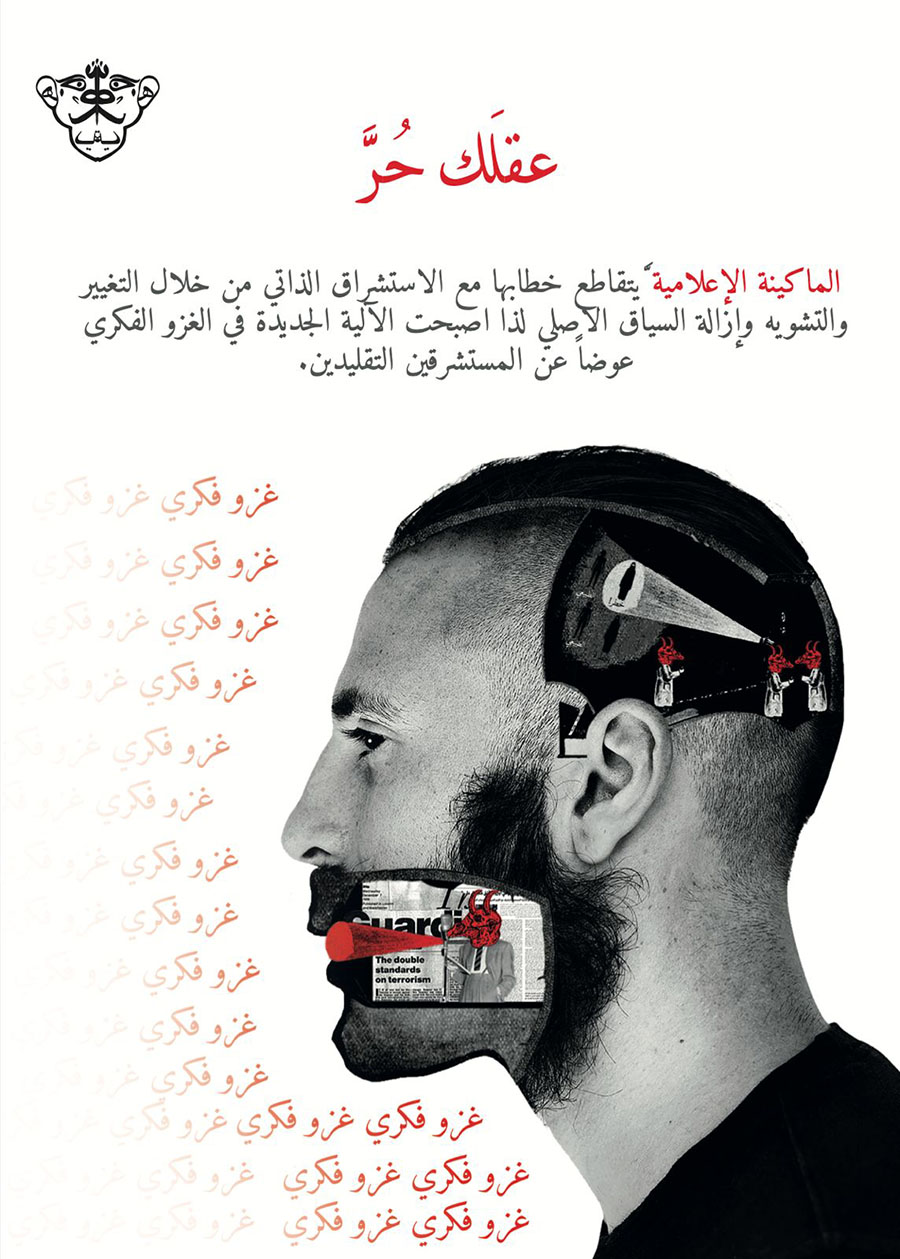

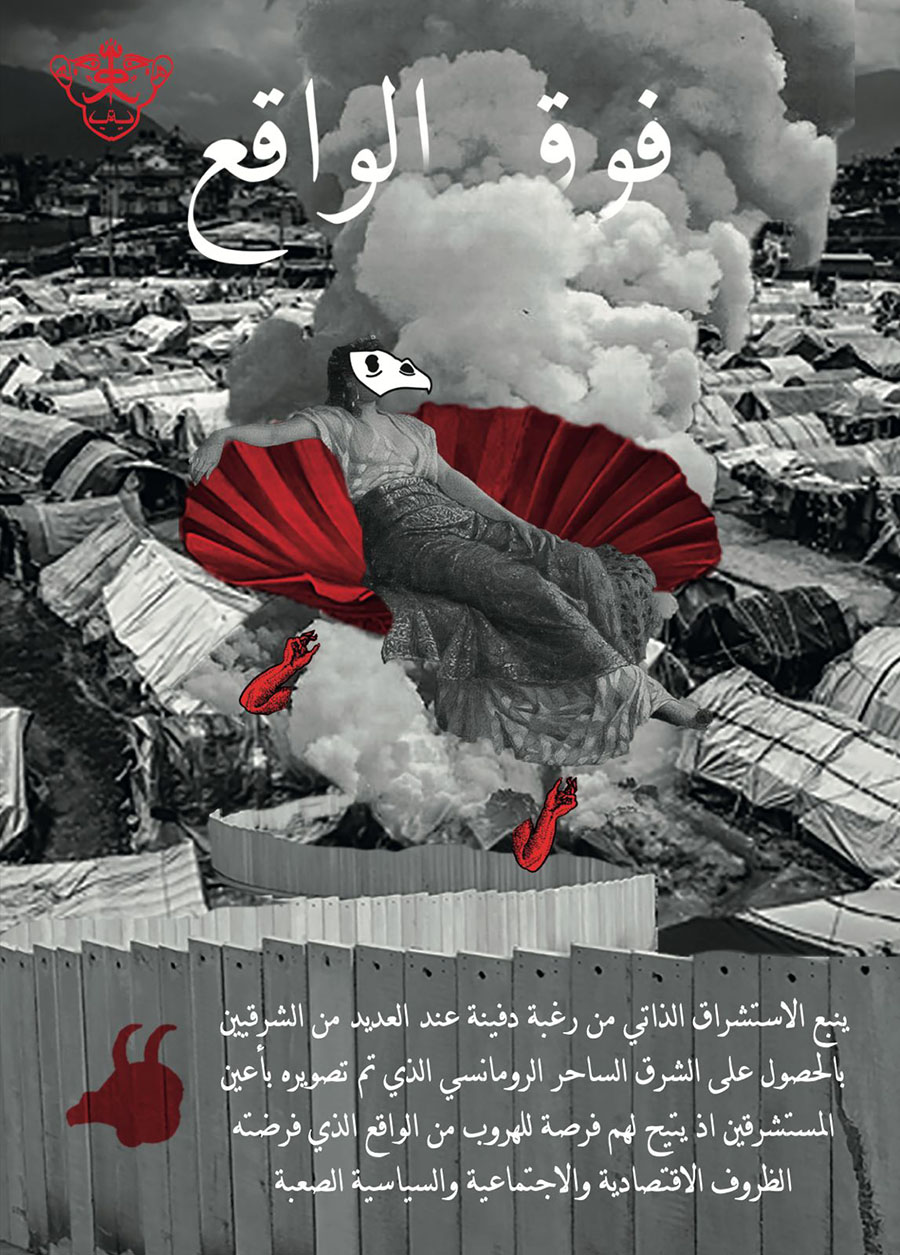

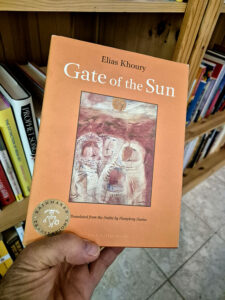

The mouth of a politician in front of a microphone, endlessly inspiring, but never able to articulate a word; a closed fist on a rock, clenching ever tighter; a flowery globe spinning in front of images of horror and struggle, to the notes of Carmina Burana… The “poetic gestures” of the international artists who responded to the call from Instants Vidéo’s attempt to answer this eternal question by summoning images from which emanate rage, dismay and distress, but also forms of solidarity and resistance, in spite of everything. A horizon that corresponds to the credo of the Biennial, supported by the Qattan Foundation, and entitled “Sin” by its curator, Salim Abu Jabal: “Sin” as the Arabic letter equivalent of x, the unknown in European mathematics, but also evoking “scene” in English and “seen” the fact of being seen. “The Biennial refuses to remain silent or to be silenced,” reads the presentation text, under the title “In Praise of the High Shadow” — words taken from a poem by Mahmoud Darwich written after the Sabra and Shatila massacres in 1982.

Resisting Through Dance

Gaza as video game “where you are the hero,” where each “clickable” scenario reveals an aspect of oppression in the enclave, even before October 7, 2023: this is the choice of distancing through the absurd made by Palestinian artist Shereen Abed Al Kareem, in her video From the Hole of a Needle. In contrast to this hard-hitting irony, for others, dance seems to be the final means of saying something about the tragedy of Gaza, and more broadly about the attempted annihilation of Palestine and Palestinians. In her video Adentro y fuera (Inside and Out), French-Spanish artist Brigitte Valobra, dressed in a white shirt and black pants, moves slowly, in a movement first centered on herself, then open to the world, as her gaze rises towards the camera. “It’s a double movement, of introspection then openness, a breath, which resonates with the resistance of women in Gaza,” comments the artist during the exchange with the audience following the screening.

Echoing this, British artist Emilia Izquierdo delivers a beautiful “Ghost dance.” On the screen, sketches of dancing bodies are superimposed on videos showing Palestinians performing a dabké (traditional collective dance of the Middle East) under fire from the Israeli army during the March of Return in Gaza in 2019, as well as American Indians circling in this “ghost dance,” or black South Africans from the time of the struggle against apartheid. “There’s nothing decorative about these dances; their function is to summon the ancestors and express indigenous resistance to the oppression of a colonial power,” explains the artist, present via a video call for discussion with spectators.

Between two bursts of video art, we go out to breathe a little in the sun. Ashtar Muallem, a circus artist from Jerusalem, carefully peels a prickly pear. Like a reminiscence of her childhood in Palestine. “I have the privilege of being able to travel easily between Jerusalem and France, because I have an Israeli passport,” explains the young artist. But her revolt against Israeli oppression of the Palestinians is no less great. This revolt, mingled with pain and — again and again — the will to fight, will be omnipresent during the round-table discussion which opens after the first three screenings, at the end of the afternoon.

To support Gaza and Palestinians, Ma’an is organizing an exhibition/sale at the

Art-Cade gallery in Marseille, from November 14 to 30, 2024.

How to be a Palestinian Artist after October 7?

The set features five Palestinian artists and two French researchers working on contemporary art in the Middle East. Journalist Lyana Saleh begins by giving the floor to the artists who survived Gaza. “The most difficult thing for me today is to behave like a good virtual father,” begins Mahmoud Al Haj. This visual artist, who works with images derived from architecture and urban planning, arrived in France last July, but his wife and three children remained in Gaza, because he was only able to raise the sum required for passage to Egypt for one adult. “I came in the hope of getting them out afterwards. It was a very difficult decision to make… But the aim is to be able to offer them a better future.” You can see the heartbreak on his face. “My greatest joy right now is receiving a 30-second video of my daughter learning to dance.”

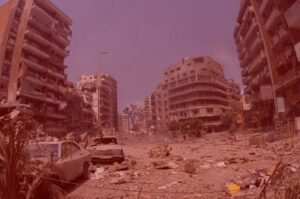

By his side, Mohamed Abusal, a leading contemporary artist known internationally for his installations, paintings and videos (notably Un métro à Gaza), was able to leave Gaza with his wife and five children. “When the Israeli army ordered us to leave, I looked at my house with all my works… But at that moment, obviously, the most important thing was that my family survived.” In the end, he managed to take fifteen paintings with him, out of 30 years of prolific artistic production. His house, like Mahmoud Al Haj’s, has since been destroyed by Israeli bombs. “During the genocide, I forgot that I was an artist. I was just a human being trying to survive: I spent my days looking for water, food, electricity to charge phones...” Mohamed Abusal and his family were displaced six times in the space of a few months, before managing to escape the nightmare of Gaza. He then obtained a visa for France and landed in Marseille, where he is currently being housed by La Friche before being able to move into a larger apartment in the Belle-de-Mai district.

Mohamed Abusal and Mahmoud Al Haj were accompanied on their odyssey to France by the Ma’an (Together) collective, founded by Marion Slitine, an anthropologist specializing in the Palestinian art scene, and Charlotte Schwarzinger, who is writing her thesis on contemporary Lebanese cinema. The “What Palestine Brings to the World” exhibition was underway at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA), Paris, when the Israeli offensive on Gaza began, in the wake of the October 7 massacres. Marion Slitine was co-curator, with the intellectual Elias Sanbar. “Among the artists exhibited at the IMA, some twenty were in Gaza. We set up a committee to support them, and enable them to be welcomed in France,” says the anthropologist. “But it’s only temporary. We don’t want to participate in ethnic cleansing and the brain drain,” she insists. “After that, it’s up to each individual to choose whether or not to stay in France.” Today, five of these artists have benefited from the Collège de France’s PAUSE program, and are hosted for at least two years by a French cultural structure. Ten others are also winners of this program, but are still stuck in Gaza. “Of the hundred or so structures we contacted, some said ‘okay, we’ll take part, but we mustn’t say so’, for fear of losing funding,” stresses Marion Slitine, who nevertheless notes that “Palestine has once again become central to political agendas.” To continue its support, Ma’an is organizing an exhibition/sale at the Art-Cade gallery in Marseille, from November 14 to 30, 2024.

Art as Memory

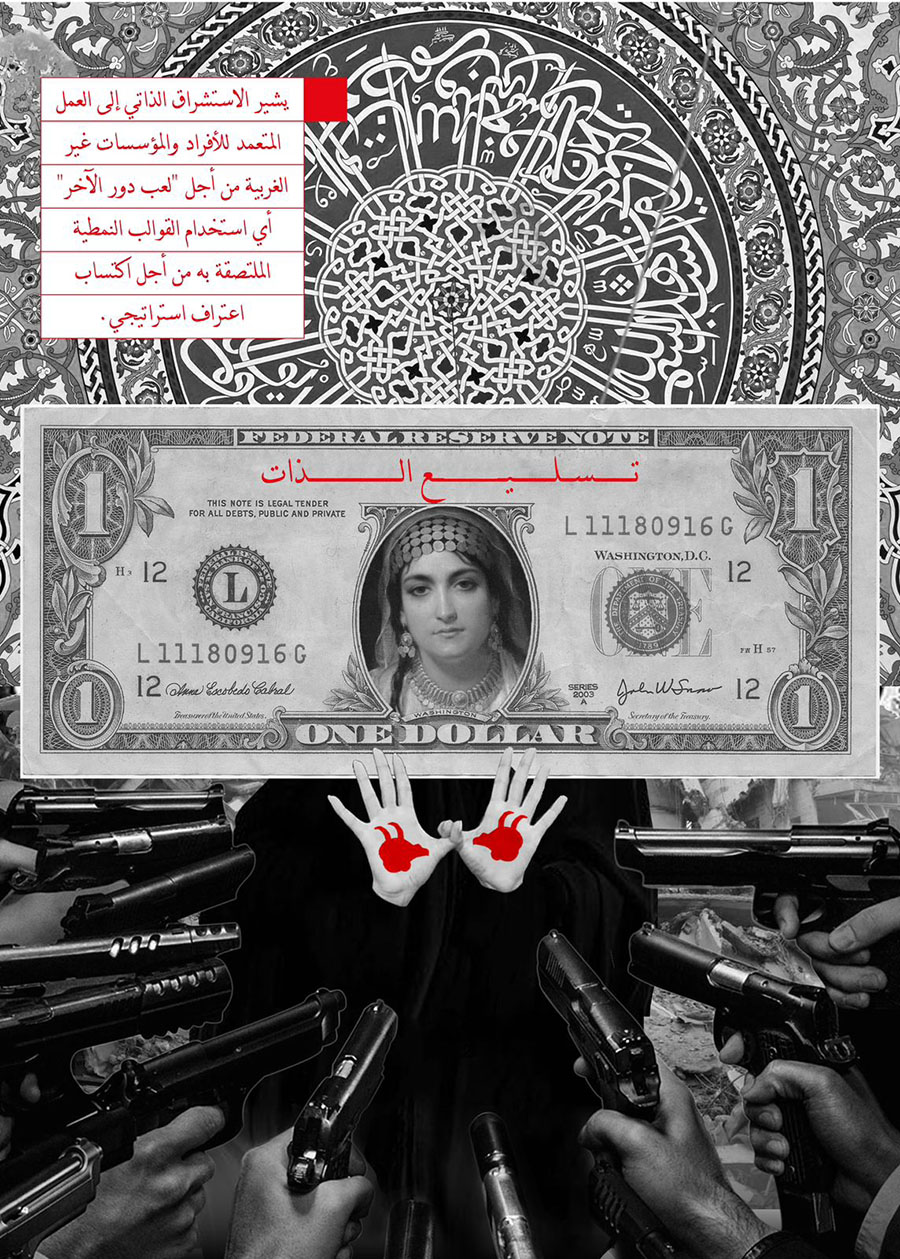

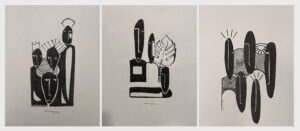

If the massacres committed by Hamas on October 7 and the genocidal war that followed have tragically put the Palestinian question back at the center of concerns, what does this cataclysm change in the artistic work of the five people present? “As Palestinians, when we express ourselves, we always walk on eggshells, so as not to be perceived as extremist or anti-Semitic,” first recalls Sireen Al Araj, a young visual artist from Tulkarem. “For a long time, we were portrayed as victims, massacre after massacre, without any action from the rest of the world. Then we adapted our way of speaking so that we were seen simply as human beings, but that hasn’t worked either, since the atrocities have continued for a year now,” the young woman observes, as her graphic works scroll across the screen behind the speakers. “We’re a people under occupation and we have the right to resist,” she says. She also says she now wants to address her art more to Palestinians than to a foreign audience.

From the same generation, Ashtar Muallem has a similar position. “Since the genocide began, I’ve stopped wondering all the time whether I’m doing the right thing or not. I no longer want to be in reaction, but in action,” says the circus artist. She recounts how, in November 2023, when demonstrations in support of Palestine were banned in France, she went to protest on the Corniche, in Marseille, walking slowly for hours, wrapped in a long red cloth, her hands and face stained red. “It was impossible for me to remain silent, to do nothing.” She also believes that French audiences have “developed new neurons” in relation to Palestine over the past year, and that her show is now received differently. “I don’t give a damn about being politically correct today. And sometimes you have to sting to make yourself heard and create debates,” she concludes.

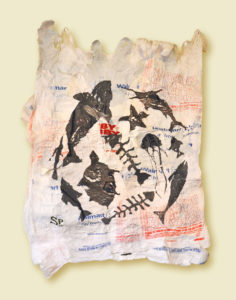

“I’ve often used fairly abstract materials in my previous work,” explains multimedia artist Manal Mahamid, originally from a town near Haifa, who now lives in Ireland. “But today I feel the need to convey a more concrete message. This she does with delicacy and humor in her short film De Akka à Gaza (From Akka to Gaza), in which a kind of flying fish travels across Palestinian territory between the two cities to the north and south. “The question I ask is: “What kind of creature do we have to be to be able to move freely from one point of Palestine to another?” she asks, evoking her experience of the colonial power’s control over her movements in Israel, even though she is officially a “citizen” of the Hebrew state. While denouncing the silence of most cultural institutions on the atrocities perpetrated by the Israelis over the past year, she insists on the role of artists in the face of the cataclysm. “We, the creators, must express ourselves to push for an end to this genocide. For me, it’s a duty to my people.”

For the two Gazan artists, in such a painful, traumatic and tetanizing moment, art has become a therapeutic or memorial tool. “I’m not producing new things at the moment, I’m blocked by the ongoing genocide,” testifies Mahmoud Al Haj. “I use art to save my memory. And to save myself, psychically.” He recounts how he expected to see his house destroyed, and created 3D scans of it. Perhaps a work of art will one day emerge from this 3D print of a Gazan house, as a symbol of its resurgence in another form.

Restoring Gaza’s lost artistic heritage via the digital medium is the aim of the Sahab Imaginery Museum (Cloud Imaginary Museum) spearheaded by Mohamed Abusal and 3 other artists. “This project began in 2021, but of course it has taken on a much stronger meaning now that all the works we want to bring together there no longer exist,” explains the artist. Here too, the idea was to digitize the monuments and works very precisely. “But as all that is destroyed, we’re going to collect oral memory or photo albums, particularly those of families who have totally disappeared.” The Cloud Museum, like a final battle against the erasure of the Palestinians, in this struggle begun a hundred times over to try and still imagine a future, beyond the catastrophe.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

Todos los días siento una gran tristeza, Estados Unidos y Europa se han vuelto monstruos

Well, as the mother of a daughter who was born of a violent &;impregnating rape by her father from Bethlehem. Fuad Nackleh Kattan. A rbetraying rape so horrific that I blocked its memory for 52+ years. The horror which never ends. As his abandoned daughter born of his rape has tried so hard to be accepted by her birth father. As she has always felt more Palestinian than English despite the evil Kattans callous rejection of her. Only to be weaponised, demonised and ostracised by Fuad, Micheline Dabdoub-Kattan, Fadi Karim & Muna Katan. Who all spiel reverence for all humanity as despicable hypocrisy. To a fawning European media who bow down to Fadi & Karim Kattan’s ‘token Frères de Guerre! So why do they not put their courage to the test & volunteer in Gaza. How the starving Gazans would be so thankful for Franco Palestinian Chef Fadi Kattan’s cooking! Do read: I WENT TO BETHLEHEM TO FIND MY FATHER & A NATIVE DAUGHTER & BANKSY Confront the Wall – by Liza Foreman It is online.. To read Fuad Kattan’s reviled eldest daughter’s elegant account of Micheline & Fuad Nackleh Kattan’s heinous inhumanity shown towards his eldest daughter born of his betraying rape of me. All real & hideous Palestinian dramas are here. Ya haram! But thankyou to the Chancellor of Bethlehem University for trying to encourage the KATTANS to behave as decent humans to his reviled daughter born of his rape. Alas he failed. The London Met are now investigating my recently reported historical rape. As thr heroic Gisèle Pelicot says: THE SHAME-HAS TO CHANGE SIDES…..

Reply

Reply to Rose Murphy

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Hola, buen día. Excelente artículo! Muchas gracias! Serían tan amables de proporcionarme el nombre de la Obra de Sireen El ALraj, en la que aparece la figura de la mujer y el billete ? así como el año de creación, o bien, cómo contactar a la autora de la obra? Muchas gracias de antemano y reciban saludos cordiales, desde México.