Aomar Boum

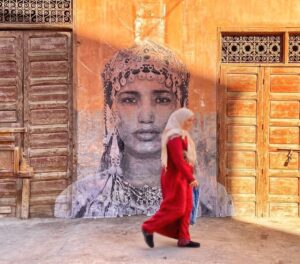

Migration remains one of the most challenging issues that face Middle Eastern and North African countries. Morocco continues to encounter unique hosting challenges as tens of thousands of sub-Saharan African immigrants and Middle Eastern refugees settle in its cities for short- or long-term periods as they wait for opportunities to transit to Europe. Morocco is bound by its bilateral security agreement with the European Union to police both its youth and foreign nationals who attempt to emigrate to Europe. Illegal migration as a phenomenon has spurred vibrant responses from writers, filmmakers and artists in Morocco and beyond.

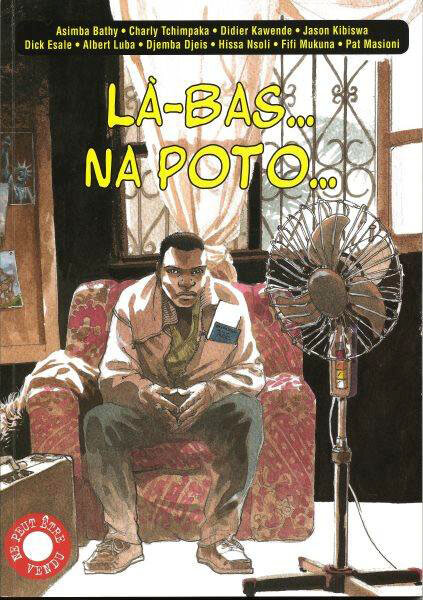

Illegal immigration (locally know as H’rig) has not escaped an emerging movement of comics in Africa. In 2007 a group of Congolese artists sounded the alarm about the negative consequences of illegal migration through a publication Là-bas… Na Poto… Published by the Belgium house Les Croix-Rouge and the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo, 125,000 copies of this collaborative work were distributed to the general public for free. The idea behind the comic book was to educate the general Congolese public about the experience of migration and the toll it takes on both individuals and nations. Na Poto (meaning Europe in Lingala) is not an El Dorado as many Africans believe, but rather a space of personal, social and economic struggle. Without denying the existence of few cases of successful African immigrants in their host countries, these Congolese artists caution youth about the danger of leaving the comfort of home unless the reason they wish to relocate is to complete their education.

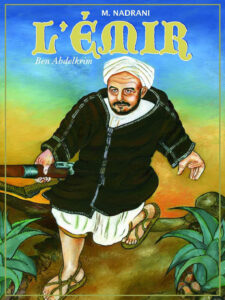

During a comic festival in Algiers, Jean-François Chanson, a French illustrator who settled in Moroco and opted to collaborate with indigenous North African artists and express the primary concern of the region, learned about this educational initiative to use graphics to educate African youth about the mirage of migration and decided to reproduce a version of this project in Morocco. Chanson, who is known by his pen name Mostapha Oghnia, teaches physics at Lycée Descartes in Rabat. He is a French artist who has published several children’s books by Éditions Yomad, namely Le Poisson d’or du Chellah, Hicham et le djinn du noyer and Les legends de Casablanca. He published his first comic books Maroc Fatal (2007) and Nouvelles Maures (2008) with Miloudi Nouiga (Éditions Nouiga). In 2010 he published another comic book Tajine de Lapin in French, Moroccan Darija dialect and Tamazight. With Saïd Bouftass, a professor of fine arts at the Institut National des Beaux-Arts in Tetouan, Oghnia co-founded Alberti, the first company that specializes in the publication of comics in Morocco or North Africa.

Influenced by the Congolese project Là-bas… Na Poto… Oghnia invited a number of artists in Morocco to contribute to a series of comics on migration. Published by Nouiga in 2010 in a collection with contributions titled La traversée dans l’enfer du H’rig, this collective comic book included three contributions by Abdelaziz Mouride, along with his students Malika Dahil, Ismaïl Ezzeroual and Issam Bissatri; and they are respectively entitled “Mirages,” “Virée vers les Abysses” (Journey to the Abyss) and “Au Village.”

While the work included some of the leading names of graphics in Morocco and Africa such Afif Khaled, Larbi Babahadi, Miloudi Nouiga, Ahmed Nouaiti and Mohammed Arejdal, the artistic work co-signed by Mouride caught my attention particularly for its mentoring and pedagogical aspects. The first thing one observes about these pieces is the fact that in all of them Mouride is the second author. Although a very famous artist, Mouride’s name is second to his students’ to show that a new generation mentored by him is here to lead a new culture of comics in Morocco. The second aspect is pedagogical and it pertains to the fact that the works depict migration as an illusion and a fantasy that is supposed to change people’s lives like a magic wand, but in reality does not.

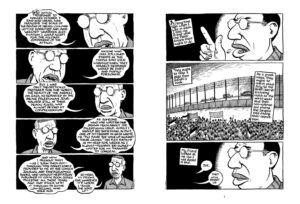

A founding member of the Marxist-Leninist Group 23 March Movement at the end of the 1960s, Mouride was arrested in 1974 and condemned to more than twenty years in jail. In prison he clandestinely drew his daily thoughts in solitary confinement and succeeded to hide them from his guards. In 2001 he was able to publish his jail work under the title On affame bien les rats (Éditions Tarik & Éditions Paris Méditerranée). Unlike many political prisoners who opted for the medium of prison narratives, Mouride chose the BD (bandes dessinées, or comic strips). After his release he joined the École des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca as a professor. In 2004, he launched with his students the first BD journal titled Bled’Art; it had a short life and saw the release of only a few issues.

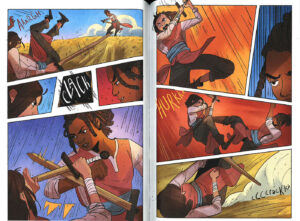

The first piece titled “Mirages” is co-authored by Malika Dahil. It shows four underaged girls in a room making a carpet under the watch of an old woman. The artist’s focus zooms in on the face of one of the female workers, and then her eyes, which leads to a set of images of the girl in Paris in a romantic relationship before the male lover disappears and the girl falls into a melancholic state. The dream is interrupted by the old lady pulling the girl’s hair and asking her to resume and focus on her work. This powerful comic sheds light on different social issues, including underaged girls in the labor market and the imaginary view North Africans have of Paris and Europe in general. The fact that the girls are making carpets probably for European tourists adds another layer of meaning to the comics, in that they show the economic unevenness between Europe and Africa. Dahil’s choice of a female character highlights her consciousness about the absence of comics that represent women in or and migration.

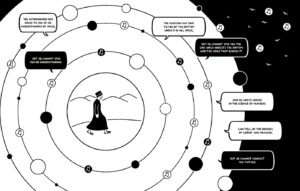

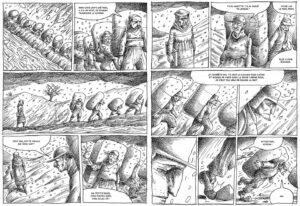

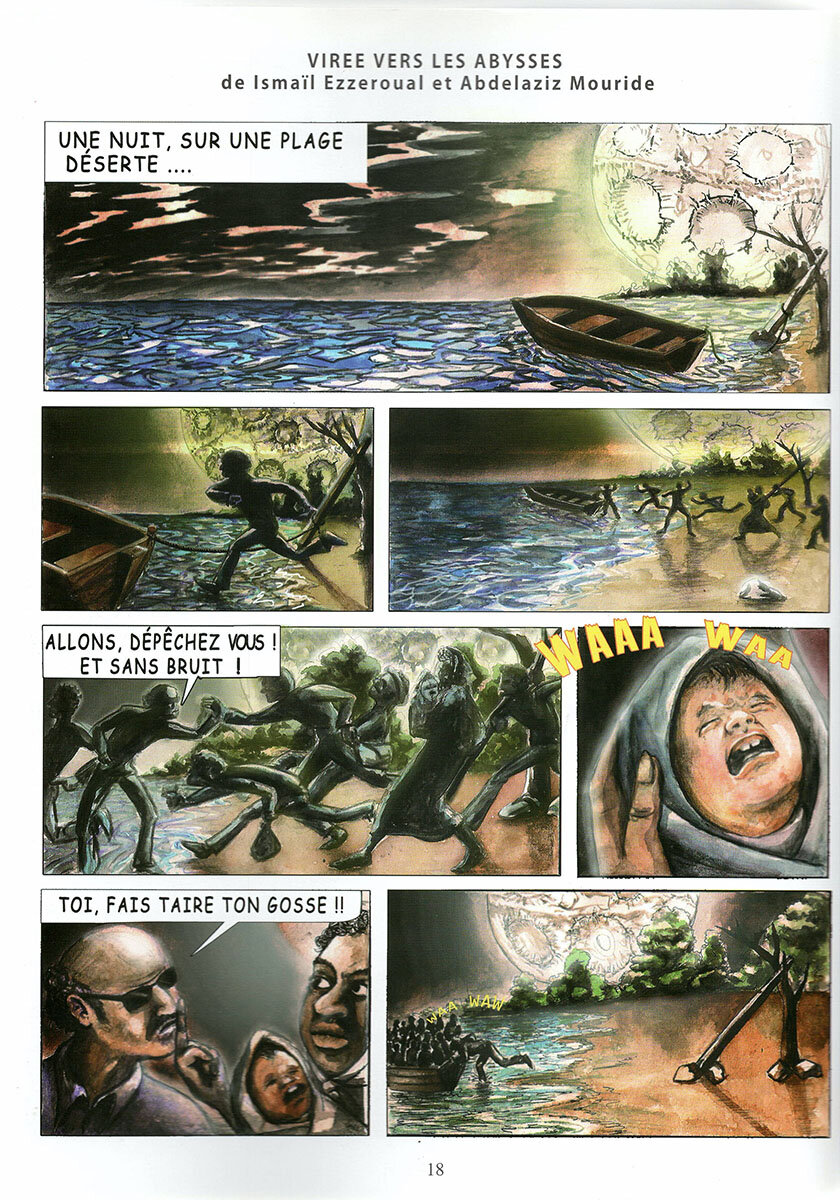

The second piece, “Virée vers les Abysses” is co-signed by Ismaïl Ezzeroual and Mouride. It highlights a different style of drawing and focuses on a group of migrants in a boat in the middle of the Mediterranean sea, arguing about the cry of a baby, water, etc, before their boat capsizes and they drown. This comic strip deploys a motif that has been already covered in literature by Laila Lalami’s Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005) and which attempts to imagine what happens on a boat filled with immigrants who all seek to survive to make it to the other side. The scene ends with a television news report on the event and a quick shift to a sports update, thus reducing a rich story to a headline in the news.

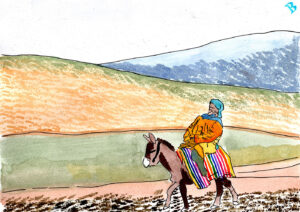

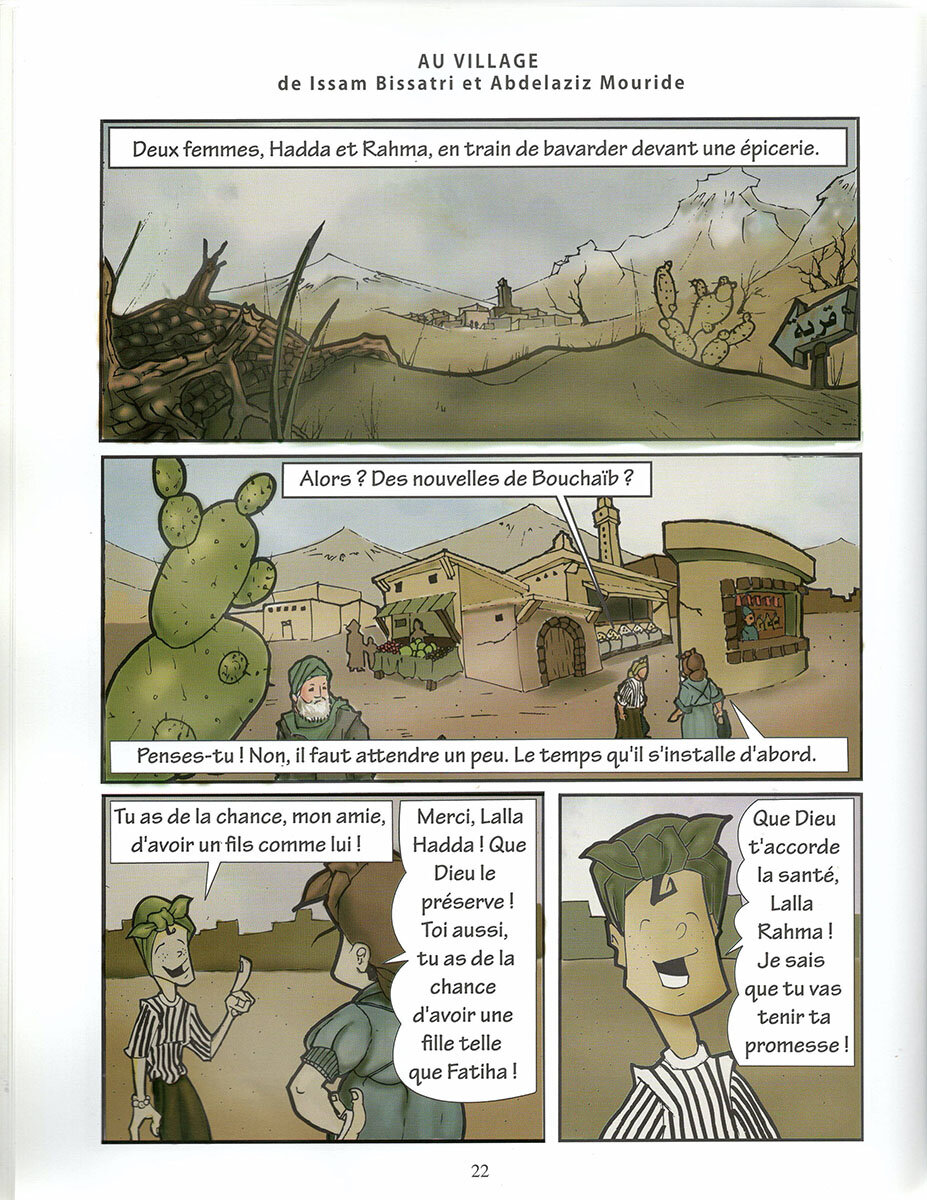

The third piece is titled “Au Village” by Issam Bissatri and Mouride. It is not just potential immigrants who live the mirage of immigration as a source of social promotion. Their family members also participate in sustaining the illusion of migration as if it were a magic wand. Bissati’s and Mouride’s piece describes the illogical expectation of families from their illegal migrants. The comics describes a mother waiting for her son to change her life, to pay her debt and achieve a new social status in the village, only to find out that he never made it to Italy. The success of this collective work should not, however, hide the challenge of making comics in Morocco and the Middle East in general, even with mentorship and institutional support. While Mouride managed to build a network of artists with Oghnia, Nouiga and others, the process of building a comics culture in Morocco is slowed down by the burdensome financial cost of making and publishing them. Support to artists usually comes from their own private networks, which do not have endless resources. On an institutional level, the gains made by BD publications in Arabic, French, Tamazight and Darija have yet to capture the attention of the Moroccan ministries of education and culture. It is high time these two ministries tapped into the rich landscapes of artistic skills that exist in Morocco and draw upon them to capture different social, political and economic themes like migration with the purpose to expand the medium of educational resources to the large audience of young Moroccan and North African populations in their diverse languages.

The third piece is titled “Au Village” by Issam Bissatri and Mouride. It is not just potential immigrants who live the mirage of immigration as a source of social promotion. Their family members also participate in sustaining the illusion of migration as if it were a magic wand. Bissati’s and Mouride’s piece describes the illogical expectation of families from their illegal migrants. The comics describes a mother waiting for her son to change her life, to pay her debt and achieve a new social status in the village, only to find out that he never made it to Italy. The success of this collective work should not, however, hide the challenge of making comics in Morocco and the Middle East in general, even with mentorship and institutional support. While Mouride managed to build a network of artists with Oghnia, Nouiga and others, the process of building a comics culture in Morocco is slowed down by the burdensome financial cost of making and publishing them. Support to artists usually comes from their own private networks, which do not have endless resources. On an institutional level, the gains made by BD publications in Arabic, French, Tamazight and Darija have yet to capture the attention of the Moroccan ministries of education and culture. It is high time these two ministries tapped into the rich landscapes of artistic skills that exist in Morocco and draw upon them to capture different social, political and economic themes like migration with the purpose to expand the medium of educational resources to the large audience of young Moroccan and North African populations in their diverse languages.

Oghnia and Mouride were able to adjust to these challenges by creating a relationship within Nouiga and other private publishers and donors who believe in the power of comics to educate. They helped train and support a generation of artists who are filling the artistic void today. Yet without sustainable institutional organizations, the work of Mouride will continue to be a drop of water in a desert of official neglect of the comic industry in Middle East and North Africa.