Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s current exhibition is on until the 15th of October, 2023, at the Tate St. Ives in Cornwall. Earthbound Whisperers explores relationships between bodies and landscapes and how surfaces accumulate traces of histories within…

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The landscape of memory in modern Turkey has been largely shaped by interruptions and discontinuities, sometimes violent, and contemporary artists have often responded to this challenge by means of historical reconstructions and encounters that bring us closer to a recent past that often seems completely buried and absent from the collective imagination. Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, an Istanbul native, is one of those artists, whose practice reenacts lost moments from the past as if they had persisted into the present, subtly confronting hidden historical narratives with images of the present, in which the ghost meets the presence. In her sculptural installations, we always encounter architectural or archival elements that carry within them traces of the disappearance. In her extended journeys through islands, bodies of water and monuments, we grasp temporarily at metaphors for these shifting sands of this memory, continuously re-writing the past.

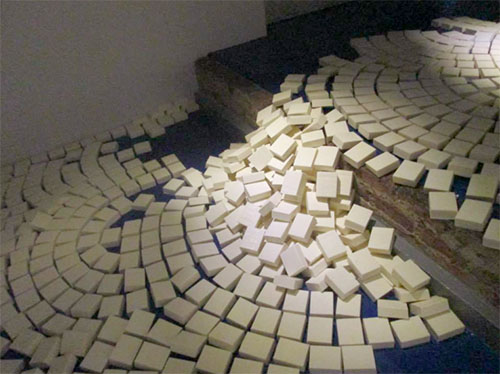

There are two stories concerning a hammam, an Ottoman bathhouse, separated by a decade in time, but also by a series of spatial movements and material reflections, between cities, bodies of water, political events, historical periods, subterranean currents and islands. When Büyüktaşçıyan opened her exhibition In Situ (2013) in Istanbul, as part of a residency at the now defunct PiST in the spring of 2013, the ephemeral installation was an act of remembrance that conjured up images of a historical hammam in the neighborhood of Pangaltı where she was born, and home to one of the last Armenian communities in Turkey. Made entirely from bars of Turkish bath soap, recognizable by their characteristic citrus fragrance, the symbolic reconstruction of the hammam, performed the role of preservation in situ, a term used in archaeology to refer to the conservation of an archaeological asset in its original location.

The Pangaltı hammam was demolished in 1995, with the promise that it would be rebuilt, but it was replaced by a hotel instead. The hammam vanished without leaving any traces, other than a black and white photograph from the 1970s. The exhibition was interrupted when the Gezi Park protests broke out in Istanbul a few weeks later, in an attempt to halt the demolition of the park, which soon escalated into violence that reshaped the country ever after.

A decade later, this summer, Büyüktaşçıyan turned to another hammam, this time the Turkish baths on the Greek island of Chios, built in the 18th century and restored in 2012, to present another work, “An Ode to a Distant Spring” (2023), set in the hot room, using long paths of blue fabric, dotted with small pieces of the iconic soap. It symbolizes the absent flow of water as a metaphor for fluid memories, migrations and unstable histories.

The installation is part of the exhibition My Past Is a Foreign Country, organized by Deo Projects, reflecting on the multilayered history of the island as a borderland; only 20 kilometers away from the Turkish coast. Once again, the relationship with the site became a post-facto reflection of the meeting point between past and present: The Turkish baths carry memories of displacement from the Asia Minor refugees it hosted after the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s, and then again, from the refugees fleeing war via the Eastern Mediterranean pathways, in the previous decade, temporarily hosted nearby. Chios was heavily affected by a devastating earthquake in 1881 that also destroyed many houses on the Turkish coast. The effect of the slippery surface of water in the installation recalls the instabilities of the present in the region: Earthquakes, refugees drowned at sea or the constant threat of unrest.

In between this long decade, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan has returned many times to absent waters and present islands, sometimes real, but sometimes also metaphoric archipelagos of time or history. It began on the Princes’ Islands in the Marmara Sea where she lives, home to the remnants of minority communities that survived the nationalist violence of the 20th century. In one of her early exhibitions, The Land Across the Blind (2014), at the now also defunct Galeri Mana, the artist begins to reflect on the uncanny relationship between islands, waters, instability and histories: An oversized sculpture of an unbalanced iron-cast balcony, small drawing studies of unstable structures, and elements suggesting being submerged underwater such as a marine rope or blue markings on the windows and the drawings, connect with the narrative of a mythical journey between the islands, Istanbul and different historical times.

Across the blind is an expression found in ancient historians in reference to Byzantion, the Greek city that preceded Constantinople, founded by Byzas of Megara in the Hellespont. Büyüktaşçıyan interweaves the story of the arrival of the Megarans to the city via the Marmara, with later journeys of Byzantine political dissidents being exiled to the islands and blinded upon arrival with a hot iron rod, and finally with her own daily ferry commute between the islands and the city. The narrative might seem at first detached from the present, but it echoes the profound transformations of Istanbul’s modern history and the ways in which other forms of historical memory that do not fit into the nation state paradigm, have been discarded as if submerged underwater. Their traces are still scattered in places, as the artist has shown in works from this period, intervening on Byzantine-era underground cisterns and recently unearthed monasteries in the city.

The Princes’ Islands is a place she would return to time and again, in two group exhibitions devoted to historical sites of minorities’ heritage. “The Wave of All Waves” (2018), shown in 206 Rooms of Silence, at the Galata Greek Primary School in Istanbul, is a sculptural installation made of wood planks, chronicling the partial collapse of the Prinkipo Greek Orthodox Orphanage on the island of Büyükada and its innovative wave-like architecture, designed by Ottoman-French architect Alexandre Vallaury at the end of the 19th century and one of the largest wood structures in Europe. A year later, in the exhibition Deep Current at the Theological School of Halki, home to one of the oldest Greek libraries in the world, her bronze sculptures “Fishbone III” (2019), set on pupils’ desks in a classroom, remind us of their absence since the closure of the seminar in 1971, when it was shuttered by the Turkish state.

View a broad selection of Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s work.

Both buildings bear traces of political violence in the recent past, largely affected by the Cyprus crises in the 1960s and 1970s, after which punitive measures were taken against institutions of the Greek community in Turkey, leading to their closure and the forced displacement of populations. The blurry photograph of the Pangaltı hammam would return again, to tell us a different story of displacement, this time on another island: It appears in the book of Büyüktaşçıyan’s presentation in Armenity, the Armenian pavilion at the Venice Biennial in 2015, at the Mekhitarist Monastery on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni. There Büyüktaşçıyan recounts her happy childhood in Pangaltı and her excitement at joining the local Mekhitarist school, learning the Armenian language, but once again, a temporal gap occurs and we’re thrown back to a more distant past, to follow the journey of Mekhitar of Sebaste.

The Armenian Catholic monk set off from his hometown of Sivas, in Eastern Anatolia, at the end of the 17th century, to found a religious order in Constantinople, and then later, the order escaped Ottoman persecution and moved to the island in 1715, at the invitation of the Venetian Republic. One of Büyüktaşçıyan’s works, the kinetic sculpture “Letters from Lost Paradise” (2015), forming letters of the Armenian alphabet, reflected on her relationship with the language as an Armenian living in Turkey, and the paradoxes of identity and heritage: How can you be called diasporic when you are still living in the ancestral lands of Armenians? As a Greek Armenian from Turkey, Büyüktaşçıyan’s work disestablishes the monolithic narrative of Turkishness through expanded narratives beyond the present political borders, subtly shedding light on lesser known, colonial histories of violence, appropriation and displacement.

Büyüktaşçıyan was trained as a painter in Istanbul, but throughout her career, the artist has turned her attention to memory sites, searching for physical or psychic traces that might reawaken or expose local histories, working with the tools of different fields such as sculpture, archaeology, archives or the moving image. In his recent book, Memory Art in the Contemporary Art World: Confronting Violence in the Global South (2022), Andreas Huyssen coined a term that describes well her practice: memory art. For Huyssen, this transnational memory art was born out of the “world-wide memory boom of the 1990s, centered on traumatic pasts” and that was “accompanied by a new understanding of the way memory works.” In his view, memory began to be understood as fluid, riddled with forgetting, and subject to porosity between past and present. Accordingly, memory art is both multidirectional and palimpsestic.

But for Huyssen, memory art is not simply about the historical past, rather “a living memory in the present that would prevent such political and racial violence in the future,” however he is keen to emphasize these are not the artist activists of the prior generation, but a more avant-garde practice, centered on minor interventions of the memory landscape that set remembrance in motion. In “The Recovery of an Early Water” (2014) at the Jerusalem Show VII, to my knowledge, Büyüktaşçıyan’s first large-scale reenactment of a lost body of water, she focuses on the Patriarch’s Pool in the old city of Jerusalem, believed to have been built by King Hezekiah in 700 BCE, and completely desiccated in the early 2000s. Using her iconic blue fabric, the artist temporarily brings to life the history of the pool, but also sheds light on the fact that the site is inaccessible to Palestinians, the majority of the population in the old city.

The intricate relation between the pool, underground tunnels and other sources of water in the area, already excavated but tightly controlled and compartmentalized by the Israeli occupation, shows the intimate but largely invisible relation between colonial archaeology and the subjugation of indigenous populations. The relationship with water, and aquatic memory, a term favored by the artist, is absolutely central to Büyüktaşçıyan’s practice, and these imaginary reconstructions of waterscapes, juxtaposed to social and political transformations, have reappeared many times, from the Acquedotto Augusteo del Serino in Naples, where she recreates an abandoned water path doubling up as a sky, in From There We Came Out and Saw the Stars (2018) to the Autostrada Biennial in Kosovo, in Prizren (2021) and Pristina (2023), where she retraces the memory of waterways lost to urbanization, floods and conflicts.

In recent years, as her work has received significant attention by international institutions, it becomes clear that not only is her storytelling about the Mediterranean and its repressed memories appealing in its vast temporal scope, but it has also endowed her with critical tools to understand and intervene in heritage landscape of other geographies in the global framework of emerging postnational, and postcolonial histories. In the 1st Toronto Biennial, her installation “Reveries of an Underground Forest” (2019), is made of rolled carpets resembling the stumps of trees felled from the forests of native lands, now buried under the modern city. The patterns in the carpets could be understood as aerial maps of newly sprawling neighborhoods, but also as indigenous rock art that has disappeared with the new settlements. The same familiar carpets that immigrants everywhere have carried with them to their new lands.

Based on Büyüktaşçıyan’s research on the displacement of first nations of Canada such as the Mississaugas, the Anishinaabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples during the development of Toronto, “Reveries of an Underground Forest” is now in one of the world’s most prestigious collections, the Tate, with its history of indirect ties to colonial slavery. But as Huyssen argues, memory art draws on Western modern and postmodern strategies, “counter-appropriating them and rearticulating them from the perspective of the postcolony,” in order to challenge the dominance of the museum as the central institution of memory. The use of installation art, sometimes ephemeral, as in the case of Büyüktaşçıyan, although inherited from conceptual art’s departure from traditional sculpture, becomes here an acknowledgement of the transient nature of both art and memory.

But Büyüktaşçıyan’s work with carpets as symbols for migratory movements, begins closer to home: Inspired by a 1st century BCE floor mosaic in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, extracted from the Palace of Pergamon in modern Turkey’s Bergama, the Alexandrine Parakeet Mosaic, the artist looks beyond the current debate on restitution of antiquities, and focuses on the long-term loss of memory and identity in the city, from the removal of its antiquities in the 19th century, to the displacement of its Greek population in the 20th century. Titled after the old neighborhood adjacent to the Acropolis of Pergamon, in Neither on the Ground, Nor in the Sky (2019), the exhibition at the IFA Berlin, the installation “Foundations” (2019) invited the viewer to stroll through the imagined pillars of a space lost a long time ago, the stoa of the Pergamon Library. A stop motion film, centered on the parakeet, is set to poetry of the artist inspired by Giorgos Seferis.

When one of her most recent works, “Nothing Further Beyond” (2021), involving carpets, deployed as time layers, appeared at the New Museum Triennial in New York, it was clear that Büyüktaşçıyan had returned to her home city of Istanbul, and continued excavating its hidden memory, but this time above the ground. During the pandemic, the artist spent many lonely hours walking around the old city, one of the few activities still permitted, and began to document and draw the remnants of ancient columns, almost felled like the tree stumps in Toronto, forgotten by the roadside or used by pedestrians unaware of their past. One of those remains is the Arch of Theodosius, erected in 393 CE, now at Beyazit Square, and in fact the only known monumental arch in Constantinople, part of the large complex of a forum, built to rival Rome, and possibly destroyed by an earthquake. Numerous pieces were discovered at Beyazit in 1958.

“The Weeping Columns,” as they were known for the teardrop pattern adorning them, actually represented Hercules’ club, and the arch was commissioned by Theodosius to symbolically represent the Pillars of Hercules, the furthest point of the West. Büyüktaşçıyan’s installation uses carpets to represent layers of the columns in their present fragmentary state but also undulating waves, suggesting a tension between the hard materials of monuments, the powers of states, the solid blocks of history and the soft and fluid surfaces of time, memory and the past. In over a decade of following Büyüktaşçıyan’s practice, I am always struck by a duality between solids and liquids; the building blocks of the imagined Pangaltı hammam, suddenly liquefy in Chios, the lost waters of Jerusalem might reappear in Naples as a frozen sky, and the aquatic memory of the Princes’ Islands, becomes a metal block of time embedded in a fishbone.

In her most recent exhibition, on view now at Tate St. Ives, and the first solo presentation of the artist at a major museum, Earthbound Whisperers (2023), the physical and historical landscape of Cornwall, marks a departure from Büyüktaşçıyan’s memory sites, often associated with the cultures of the Mediterranean and the internal colonial struggles of the global south, but yet, there’s a return to elements that have shaped her thinking from the beginning — islands, drawing and archaeology. During a residency in Britain, at Tate St. Ives, the artist became interested in that boundary between culture and nature represented by megaliths, dolmens and stone circles, dating back to the British Bronze Age (2500 – 800 BCE), and constantly reinterpreted in local folklore, particularly the Merry Maidens, a stone circle at St Buryan, associated with a legend about nineteen girls who were turned into stone for dancing on a Sunday.

For an artist, who has always been interested in the lives and myths surrounding ancient sites, the vague anthropomorphic forms of the megaliths became a starting point, and she began working on large scale drawings and paper cutouts. While the origin of the megaliths remains unexplained, Büyüktaşçıyan dug into gendered local histories, and learned about a camouflage netting factory that opened during World War II, after the local silk factory closed, where women were not allowed to speak, while screaming — tying the fabric onto the fishing net, but were only permitted to sing. This curious event, a sung silence, connected the recent past with the legend of the maidens. In the end, a series of megalith drawings on slippery fabric, containing both layers of graphite on the fabric, and sculptural layers of the fabric itself, turned the exhibition into a whisper, a moment, from different simultaneous pasts.

At Tate St Ives, the drawings were placed vertically, following the orientation of the megalithic structures of Cornwall, but in a parallel exhibition, at the Gwangju Biennial (the exhibition is a co-production between Gwangju and Tate), they reflected the nature of Neolithic funerary dolmens in sites like Gochang, Hwasun and Ganghwa in South Korea, by being placed horizontally. The message of the whisper — there is a wind sound accompaniment to the Tate St Ives’ exhibition, remains undeciphered. In a career spanning almost two decades, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan has demonstrated an uncanny ability to bring visual poetry where only shadows remained, and problematize, rather than simplify, the relations of these places and events with our unbounded horizon of contemporaneity. These sites and events are not fossilized in the past; they’re changing at the same time that they’re being preserved, or sometimes forgotten.

In Büyüktaşçıyan’s work, we find not only the capricious resilience of memory, but also the viscous nature of human time, constantly melting and freezing, oozing out slowly and then suddenly breaking. It is a crumpled fabric, whose outer edges might never meet, but can suddenly split into many pathways. In their recent book, The Fabric of Historical Time (2023), Zoltán Boldizsár and Marek Tamm use a metaphor familiar to Büyüktaşçıyan, to explain the tensions between history and our experience of time: “The fabric of historical time consists of varying relational arrangements and interactions of multiple temporalities and historicities. Kinds of temporalities and historicities emerge, come to being, fade out, transform, cease to exist, merge, coexist, overlap, arrange and rearrange in constellations of the temporal registers (of past, present, and future), clash and conflict in a dynamic without a predetermined plot.”