El Guabli argues that language, gender, class, race, and geographic distribution are interdependent factors that shape citizenship in present-day Morocco.

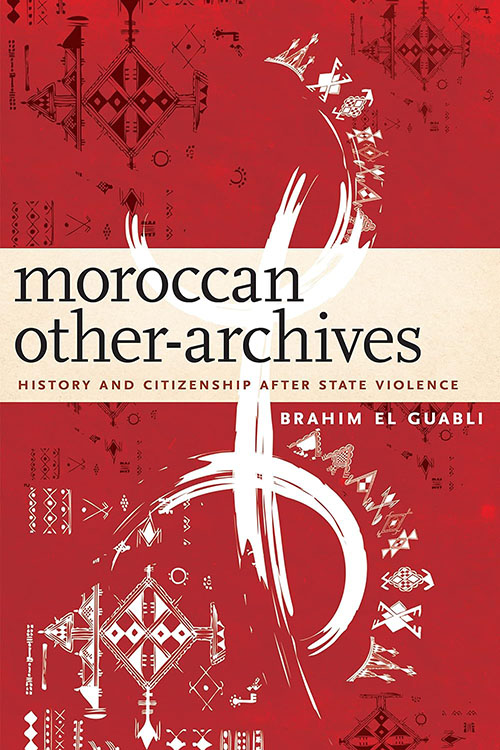

Moroccan Other-Archives: History and Citizenship after State Violence, by Brahim El Guabli

Fordham University Press 2023

ISBN 9781531501464

Hassan Benjelloun’s 2007 film, Fein Mashi ya Moshe? (Where Are You Going Moshé?), tells the story of Shlomo, a Moroccan Jewish man in the town of Boujad in central Morocco, as he navigates the difficult question of whether to remain in Morocco while his co-religionists imagine their future elsewhere. Shlomo’s(1) emotional decision, however, has implications beyond himself and his immediate family, for without a Jewish (or non-Muslim) resident of Boujad, the town’s bar will lose its liquor license, following the rules of religious authorities. Benjelloun’s film, released nearly two decades ago, addressed themes not yet commonplace in traditional histories in Moroccan academia, depicting the story of Jewish departure from Morocco in the 1960s when the majority of the community left for Israel/Palestine, France, Canada, and the United States.

Brahim El Guabli’s recent book, Moroccan Other-Archives: History and Citizenship After State Violence, addresses archival silences, such as this one, by exploring the forgotten histories of Amazigh communities of Morocco, Moroccan Jewish communities, and political prisoners in the Moroccan state — all between 1956-1999, from Moroccan independence until King Hassan II passed away.

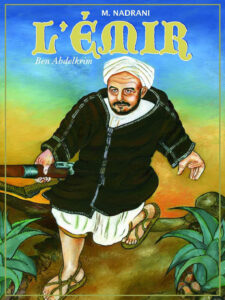

In developing a theory called “other-archives,” El Guabli, a contributing editor to The Markaz Review, seeks to center communities which have been forgotten or neglected by the Moroccan state and are therefore absent in the traditional arena of Moroccan historiography, such as Moroccan state archives. To this end, El Guabli engages a diverse range of sources, including novels, poetry, street signage, and the Tamazight alphabet (Neo-Tifinagh), among others. His work joins a number of recent works in Moroccan Jewish studies that push the boundaries of traditional historical methods and sources while also highlighting marginalized stories(2). These works include Christopher Silver’s musical history of the North African Jewish past, Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa, as well as Alma Heckman’s book, The Sultan’s Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging, which tells the story of Moroccan Jewish involvement in the Moroccan Communist Party and the eventual national liberation movement in the twentieth century. Far from a traditional historical monograph, El Guabli deftly uses approaches from the field of Memory Studies, referencing prominent Memory Studies scholars such as Aleida Assmann, Astrid Erll, and Ann Rigney(3), while also building on Aomar Boum’s influential intergenerational study on memories of Jews, Memories of Absence: How Muslims Remember Jews in Morocco. While many scholars focus on one particular subset of Moroccan society, El Guabli’s narrative is unique in that it weaves together the stories of Amazigh communities of Morocco, Moroccan Jewish communities, and political prisoners of the Moroccan state through his other-archives theorization that challenges what has traditionally been considered a legitimate archival source. Additionally, his bibliographic corpus of counter-canonical works referenced throughout Moroccan Other-Archives is a crucial contribution to the field of Moroccan studies.

In the first chapter of the book, El Guabli begins with a historical overview of the Amazigh community’s response to state repression of their history and culture following Moroccan independence in 1956, in what he calls the “re-Amazighization of Morocco’s history.” He highlights the various ways that Amazigh activists and academics made space for Amazigh culture in the public sphere. These efforts were not limited to public space but extended to historical writing about Morocco, as seen through Ali Sidqi Azaykou’s historical writing, exemplified by his article “Tārīkh al-maghrib bayna mā huwwa ʻalayhi wa mā yajibu an yakūna ʻalayhi” (History of Morocco Between What It Was and What It Should Be). Chapters two and three focus on “Muslim-Jewish” Morocco to show how Moroccan Muslims today have depicted a past that no longer remains in the Moroccan present; while a sizable Moroccan Jewish community exists today, primarily in Casablanca, the departure of the majority of Moroccan Jews during the first two decades of Moroccan independence undoubtedly changed the fabric of Moroccan society. El Guabli shows how non-Jewish Moroccan authors have wrestled with this loss, fictionalizing both pre-colonial Muslim-Jewish interactions (in what he calls mnemonic literature) as well as fictionalized narratives of Jewish departure from Morocco.

In the fourth chapter, El Guabli turns to the final community in his effort to push back against the canonical historiography: victims of the Tazmamart prison, a secret facility in southeast Morocco designed for political prisoners during the Years of Lead (1956-1999). In addition to analyzing prison literature that aims to portray the experiences of political prisoners, El Guabli also outlines how the transnational movement emerged as an other-archive, with Paris as its center. In the final chapter of the book, El Guabli discusses developments in Moroccan historiography, showing how Moroccan historians have responded to other-archives and utilized non-traditional historical sources, such as memoirs or testimonies.

In his analysis, El Guabli distinguishes place from space, referencing philosopher Janet Donohoe’s notion of place, in which she notes that “space is more abstract, lending itself to mathematization and geometry, while place resists such attempts in the way in which it is imbued with value and meaning.” In each chapter of Moroccan Other-Archives, El Guabli employs an analysis of place as a way for members of these forgotten histories to reinsert themselves into Moroccan society, both in a literal and figurative sense. By showing how these communities have begun carving out their place in Moroccan society, El Guabli identifies tangible strategies towards countering hegemonic state-imposed sites of forgetting(4).

In the 1960s, The Moroccan Amazigh Cultural Movement (MACM) began in earnest to build an alternative place for Amazigh people — both linguistically and culturally(5). El Guabli delineates three avenues of place-making, beginning in the 1960s and continuing into the present day: the formation of MACM, the rewriting of Moroccan historiography, and the appearance of (Neo-)Tifinagh (the Tamazight script) in public space. In theorizing other-archives as a place of memory, El Guabli engages with MACM’s historical struggle to forge a place of memory outside the mainstream approaches to memory following Moroccan independence in 1956. To create an alternative memory to the established narrative, MACM sought to introduce Moroccans to a different narrative to understand themselves as citizens of the country. This project would eventually find its way into the preamble of the revised constitution in 2011, which embraced MACM’s long-resisted approach to Moroccan identity as plural and multi-confluenced. El Guabli writes that “Al-waḥada fī al-tanawwuʻ (“unity in diversity”) has been MACM’s founding motto since the first summer university organized in Agadir in 1980.” Put differently by Mohamed Boudhan, “unity in diversity” was a path for the country to return to its roots. MACM’s efforts to create an alternative place of memory worked in tandem with academic Ali Sidqi Azaykou’s poetry, history, and toponymy work. “Unity in diversity” as a place of memory resonates with Azaykou’s approach that advocated for the “intersection and collaboration of the scholar of religion, the litterateur, the historian, the geographer, and the specialist in popular culture, among others.” Mustapha recalls the feeling of seeing Tifinagh in public space; for him, it was a moment that recognized the sacrifices Amazigh political prisoners made to display Tifinagh on the same buildings where it had previously been banned. The engraving of (Neo-)Tifinagh on institutional buildings and on street signs throughout Morocco has served as a place of memory-making to remind Moroccans of who they are and reclaim public space as Amazigh. For El Guabli, Tifinagh “rewrites history even as history unfolds in the Moroccan public sphere.”

In his chapters on Muslim-Jewish encounters in Moroccan literature, El Guabli illustrates a more literal sense of place by outlining how Muslim authors have perceived the loss of the Moroccan Jewish community. He notes that mnemonic literature creates “an other-archive — a midway between history and archive — of a Jewish-Muslim life that has long resided outside of official Moroccan and academic histories.” El Guabli cites numerous places of Muslim-Jewish interaction in this mnemonic literature, such as the home, the Mellah neighborhood, and the city (among others). While mnemonic literature is one avenue of expression for the Moroccan Jewish past, many Moroccans themselves regularly reflect on and help to preserve this history; living among the oldest remaining members of Tangier’s Jewish community last summer, Natalie remembers how the Muslim staff at the retirement home not only took care of the Jewish residents, but also maintained Moroccan Jewish traditions, which included making skhina (a Moroccan Jewish stew) every week for shabbat.

El Guabli discusses El Hassane Aït Moh’s novel, Le Captif de Mabrouka (The Captive of Mabrouka), which focuses on two Morocco-born individuals — named Richard D. and Walter Baroukh Kinston — and their experience returning to their hometown of Ouarzazate to reclaim the same childhood home. The Moroccan Jewish family sold the home to a French family when they left Morocco, and the home itself symbolizes shared notions of memory and nostalgia. El Guabli suggests that the house contains memories of the families’ pasts, symbolizing the historical processes of departure and return as well as French colonialism and decolonization. El Guabli writes that “the microcosm of the house also serves to recreate a nation-family in whose history both Richard D. and Walter Baroukh Kinston can belong.”

In Anā al-mansī (“I am the forgotten”), Mohamed Ezzedine Tazi tells a multigenerational story of the Mellah neighborhood in Fes that culminates in the 1967 war. The novel recounts the stories of Jewish characters living in the Mellah and their experiences as a result of the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, Moroccan independence in 1956, and the Six-Day War in 1967. El Guabli emphasizes how the author depicts the Mellah as a porous site of exchange and interaction. While the Mellah neighborhood no longer represents a majority Jewish space in Morocco, the neighborhood itself is a reminder of the Jewish past — one which is reimagined through Moroccan literature as mnemonic literature(6). Finally, on the city-wide level, El Guabli discusses Driss Miliani’s novel, Casanfa, where a Moroccan Jewish character named Ishaq Abitbol passes along a box containing a manuscript titled Casanfabar. His Muslim neighbor, Yusuf al-Fatimi, eventually opens the box, and the novel revolves around the Jewish character’s stories taking place in various bars around the city of Casablanca. El Guabli shows how “Casanfabar anchors a Moroccan-Jewish past in place,” while also using the Jewish calendar to measure time, so that the reader must “read a portion of Moroccan history through a Hebraic temporality.” Mnemonic literature is a place where Morocco’s Jewish past can be discussed more openly and imaginatively than what traditional historical practices had allowed.

Creating a new place of memory via other-archives proved difficult for Moroccans as Tazmamart detainees paid a high price to gain and make this alternative place of memory possible. El Guabli theorizes the places of memory of Tazmamart in three literary moments: “scandalous, embodied, and fictionalized other-archives.” The scandalous other-archive begins with a struggle to render Tazmamart believable after Moroccan state-sanctioned denial. It creates a place of memory in that it builds on the disappearance of political prisoners after the coup d’états of 1971 and 1972. Smuggled letters sent to activists such as Christine Daure-Serfaty, François Della Sudda, Gilles Perrault, and members of La Ligue des droits de l’homme (Human Rights League) and Les Comités de lutte contre la repression au Maroc (Committees Battling against Repression in Morocco [CBRM]) provided a strong motivation to fight for the recognition of Tazmamart as an embodied place of memory. With the embodied other-archive literature — the second place of memory in this chapter — the prisoners themselves (such as Ahmed Marzouki and Aziz BineBine) tell their stories through literature, and the memory and the place of Tazmamart become palpable through their experiences of suffering and agony. The embodied experience of the prison is not only engraved in their memories, but also on their bodies, as a result of torture they suffered while in prison. Mustapha remembers seeing Ahmed Marzouki in Rabat in 2016 at a conference supporting the existence of an independent judiciary in Morocco—the same institution that sentenced him to prison in 1973.

Finally, in El Guabli’s conceptualization of the fictionalized other-archive, memory transcends the scandalous and embodied other-archives to a more fictional place, with works such as Tahar Ben Jelloun’s novel Cette aveuglante absence de lumière (This Blinding Absence of Light), and Rapt de voix (Voice Theft) by Belkassem Belouch. In this moment, the literary work becomes more distant from the embodied experiences of the prisoners, especially with, as El Guabli points out, Fadel’s novel Ṭāʼir azraq nādir yuḥalliqu maʻī (A Rare Blue Bird Flies with Me), which “acknowledges no connection between the novel and any particular Tazmamart survivor’s lived experience.” This section culminates in the analysis of Radwa Ashour’s novel Farage, where the place of memory becomes more transnational — the nation-state is no longer the reference point of oppression, but instead invokes a transnational form of oppression and memory. For El Guabli, Farage brings together “the struggles of three generations of Egyptian citizens into transnational stories of oppression in Africa and the Arabic-speaking world,” where the place of memory transcends the scandalous and the embodied places of memory and becomes one that is multilayered, fictional, and transnational.

The importance of place as a site of memory, loss, and nostalgia is reinforced in Benjelloun’s film Fein Mashi ya Moshe? (Where Are You Going Moshé?). In addition to Shlomo’s attachment to Morocco as a place, the film centers around the rural town of Boujad and, more importantly to the plot of the film and the residents of Boujad, the town’s bar. Much like the bars that El Guabli discusses in Moroccan Other-Archives, the bar represents a space of mixing, hybridity, and togetherness for Jewish and Muslim Moroccans. In the final scene of the film, the residents of Boujad dance joyfully in the bar, Chez Mustapha, formerly known as Chez Shlomo. Shlomo made the difficult decision to leave Morocco, but viewers come to understand that the bar remains open thanks to the disabled Jewish man previously rejected by Zionist emissaries. The choice to end the film in the place of the bar is important in and of itself, since, according to El Guabli, “bars…serve as a medium to reimagine a bygone past during which both Jews and Muslims evolved and shared the same space of the nation.”

In conversation with the themes of the film, El Guabli’s Moroccan Other-Archives is a crucial other-archive that seeks to document and build an archive for these forgotten histories. He challenges even more recent attempts to reconstruct Moroccan historiography, noting the shortcomings of the Royal Institute for Research on the History of Morocco (RIRHM) in 2006. For this reason, Moroccan Other-Archives is an invaluable resource to scholars of Moroccan history, Amazigh Studies, and North African Literature, and paves the way for an interdisciplinary and critically inclusive approach to rewriting Moroccan history.

Notes

(1) For discussion of Moroccan Jewish history through film see, Oren Kosanksy and Aomar Boum, “The “Jewish question” in postcolonial Moroccan cinema,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 44, No. 3 (August 2012); Jamal Bahmad, “Jerusalem Blues: On the Uses of Affect and Silence in Kamal Hachkar’s Tinghir-Jérusalem: Les échos du Mellah.” In Jewish-Muslim Interactions: Performing Cultures Between North Africa and France. Edited by Samuel Sami Everett and Rebekah Vince. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020; Alexandra Shraytekh, “Haunting the future: narratives of Jewish return in Israeli and Moroccan cinema,” The Journal of North African Studies, Volume 23 (2018).

(2) Alma Rachel Heckman, The Sultan’s Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020); Chris Silver, Recording History Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022).

(3) For central works in the field of Memory Studies, see Jeffrey Olick, The Sins of the Fathers: Germany, Memory, Method (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Astrid Erll, “Traveling Memory,” Parallax, vol. 17, no. 4 (2011): 4-18; Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009). In the Moroccan context, see Aomar Boum, Memories of Absence: How Muslims Remember Jews in Morocco (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013).

(4) In contrast to Pierre Nora’s notion of Lieu de mémoire, Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations, No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory (Spring 1989).

(5) For more on the history of the Amazigh movement, see Ahmed Boukous, Revitalizing the Amazigh Language: Stakes, Challenges and Strategies (Rabat: Top Press, 2011); Paul Silverstein, “The Amazigh Movement in a Changing North Africa,” in Social Currents in North Africa: Culture and Governance after the Arab Spring. Edited by Osama Abi-Mershed. London: Hurst Publishers, 2018; Berbers and Others Beyond Tribe and Nation in the Maghrib, edited by Katherine E. Hoffman and Susan Gilson Miller (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

(6) On the history of the Mellah neighborhoods in Morocco, see Emily Benichou Gottreich, The Mellah of Marrakesh: Jewish and Muslim Space in Morocco’s Red City (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006); Susan Gilson Miller, “The Mellah of Fez Reflections on the Spatial Turn in Moroccan Jewish History,” in Jewish Topographies: Visions of Space, Traditions of Place. Edited by Julia Brauch and Anna Lipphardt. London: Routledge Press, 2016; Shlomo Deshen, The Mellah Society Jewish Community Life in Sherifian Morocco (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989).