What the atheist, nihilistic Flaubert aspired to, when he sat down to forge his words, his sentences, his paragraphs and chapters, was to replicate a book that already existed, that had already been composed by a non-human hand. In Flaubert’s mystical conception then, the process of writing was more akin to the discovery of a text that had been revealed from on high rather than the invention or creation of said text.

I was bored nearly to the point of suffocation when I read Madame Bovary for the first time. I was a teenager, a fifteen-year-old attending a French school in Lebanon, with dreams of becoming a famous writer. I don’t know what compelled me to read the novel, but I remember very well the long, dull hours spent before interminable pages of meticulous description detailing the most minute and trivial things, like the various fabrics, shapes, and colors of a hat, or the play of light on an oil painting hanging on a wall.

Around two years later, I read L’Éducation sentimentale and felt just as bored. “This man is seriously enamored of excessive description,” I huffed, but then quickly reined myself in, persuaded by Flaubert’s greatness, because surrendering to that belief was imperative if I wished to maintain the recent and thus still-fragile image I had forged of myself, as a discerning connoisseur of fine literature.

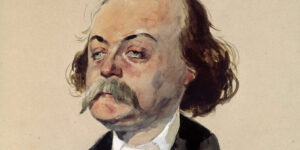

I considered my task complete: I had acquainted myself enough with the esteemed, corpulent Frenchman — he of the thick, bristling moustache that overhung and obscured his lips — and I soon forgot both him and his infamous adulteress, Emma Bovary, thinking I was done with him and would never open one of his books again.

But it seemed Flaubert was not done with me. He was not content to remain up there on his pedestal, enjoying the preternatural power it entailed in conveying boredom into the souls of his readers. He began, at first stealthily, and then more insistently, to pursue me. More and more frequently, his name kept reappearing in my readings, and little by little, a mythical image of him began to inscribe itself in my imagination. The image of the ascetic writer that had captivated so many (and from whose clutches so many had tried to break free); from his protégé Maupassant, to Franz Kafka, (who as a youth once saw himself in a dream standing before a rapt crowd and reciting, sonorously and in French, the entirety of L’Éducation sentimentale), to Mario Vargas Llosa, who devoted an entire book to Flaubert’s adulteress.

All three of these writers belonged to a gang with which I eagerly wished to identify, whose opinions, literary and otherwise, I wanted to be aligned with. This was a way of insisting that I was a great writer in the making, rather than committing myself to the disciplined, daily practice of writing. In fact, I wrote rarely, instead contenting myself with daydreams about the praises that would one day be heaped upon me — praises to which I would barely lend either importance or care. I would imagine myself, for example, upon receiving the Nobel Prize, delivering a brief and haughty speech, dripping with pearls of wisdom before an audience slack-jawed with rapture. The days and months rushed quickly by while I remained fixed in place, dreaming of fame and awaiting the advent of inspiration.

But my discovery of Flaubert’s person, through what had been written about him by this gang I so idealized, shook the foundations of my entire literary doctrine. The first thing that captivated me — and horrified me — was the pace of his work, so slow as to be astounding. I learned that he wrote ten hours a day, and that the 400 pages of Madame Bovary had taken him 53 months of continuous, arduous toil; that this man put his quill to paper daily in order to produce seven pages of writing a month; that is, only a quarter of a page during an entire ten-hour day of work; that is, 83 words a day, or eight words an hour, i.e. half a line. What’s more, he abhorred writing immensely, considering it a sort of penance for his sins, pure pain only rarely infiltrated by pleasure, a task he cursed repeatedly, seeing it as akin to the sorts of punishments meted out at school.

His slowness, his torment, was by no means attributable to a lack of inspiration but was rather the result of a constant and painstaking search for what he called le mot juste — just the right word. For Flaubert, this expression was the distillation of an entire, holistic theory on the art of writing, one that could have only germinated in a sick mind. Le mot juste did not refer to the word (or sentence) that would best or most precisely express what needed to be said but rather to the singular and only word (or sentence) that was capable of doing so. Flaubert considered that there existed somewhere a perfect convergence between meaning and form, between an idea and how it ought to be expressed. Evidence that this longed-for congruence between idea and expression had been achieved would make itself known through how the phrase sounded to the ear. Flaubert subjected all his writings to an exacting test, reading them aloud to himself in a ringing voice, his ear carefully attuned to the music of the words and sentences. Any discord he detected in the sound, no matter how minute, was conclusive proof of a serious flaw — not just in the form of expression, but in the very content of the idea behind it. And thus would ensue hours and hours of exhausting work.

This theory of convergence between meaning and form, between the truth of an idea on the one hand, and the musicality of the phrases that embodied it on the other, rests on a mystical conception of the nature of writing, one that Flaubert never clearly articulated, but whose essential qualities — along with the madness of its creator — are not difficult to discern.

The theory assumes the following: since the congruence between form and content, expression and idea, is complete and absolute, then it is impossible to replace any one of these elements with another. Consequently, we can also say that they exist both prior to the act of writing and independently of it, in an immortal harmony that is not of human creation. What the atheist, nihilistic Flaubert aspired to, when he sat down to forge his words, his sentences, his paragraphs and chapters, was to replicate a book that already existed, that had already been composed by a non-human hand. In Flaubert’s mystical conception then, the process of writing was more akin to the discovery of a text that had been revealed from on high rather than to the invention or creation of said text. That is, the attempt to write a perfect text, one that would be timeless and eternal, is ultimately the search for a text that has always existed and will always exist, prior to and independent of time.

The paradox, however, is that the writer, in his attempt to discover this eternal text, finds himself utterly alone, with no recourse to any tools other than his limited human faculties, and he will receive neither divine vision nor commonplace inspiration to aid him in his task. To find le mot juste—the exact right word, sentence, paragraph, etc.—Flaubert had no choice but to set himself to arduous, continuous toil: essentially, writing and rewriting, then listening for the music of what he had written, then rewriting anew, and so on, and so forth, until, exhausted, he surrendered.

To put it another way, Flaubert was afflicted with a neurosis or obsession for revision. Certainly, many writers place a lot of importance on revision, as it is an integral part of the writing process itself, but Flaubert took it to an entirely new level, so much so that he could no longer in fact be said to be writing; rather he was always revising. The thousands of hours he put into producing Madame Bovary were a direct result of this obsession. Flaubert never sat at his desk lost in contemplation of a blank sheet of paper; his quill was always moving, always scrawling words and sentences and then crossing them out. The pace of his output can’t really be reduced to half a line every hour; in truth, it was much more than that. Because behind every sentence that found its way into print there were reams and reams of discarded pages. And because life is short, and revision a long, nearly endless task, Flaubert found himself consigned to the life of a hermit.

What I learned then about Flaubert’s life and person filled me with dread: I saw myself as a lazy hypocrite, who believed that writing a literary masterpiece required no more than conjuring one up in a dream. I saw long years of suffering stretched out before me, and I had no confidence in my ability to endure it. What’s more, I didn’t even know if I really wanted to engage myself in such a thing to begin with.

I now believe that what attracted me to Flaubert’s theory back then was its quasi-religious nature. Or, more precisely, it was that image of the ascetic writer, willing to sacrifice all his time and energy on the altar of beautiful sentences and their music. Perhaps, what I saw in this bizarre priesthood — this priesthood of prose — was a removal not from the rabble of the rest of mankind (as I had imagined in my daydreams of winning a Nobel), but a removal from life itself.

Regardless, armed with this new theory, I decided to revisit Madame Bovary. And thus, the miracle occurred.

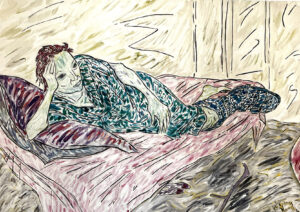

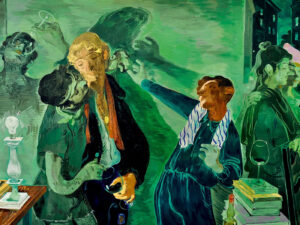

In one of the novel’s last chapters, Flaubert describes Emma Bovary’s agonies after swallowing poison, meticulously detailing her every death throe. She steals into the house of her neighbor the pharmacist, into his laboratory, and ingests some arsenic in an attempt to escape the financial disaster bearing down upon her and the social scandal in close pursuit: having racked up mountains of debt over the years without her husband’s knowledge, the promissory notes are now raining down upon her, suddenly and all at once. There is no one to save her — not her current lover, who broke his vow to help her and forsook her, nor her former lover, who had rebuffed her cruelly. And so, she lies on her deathbed, her face pale, her tongue black, a bitterness in the back of her throat, as though she had swallowed ink. She vomits repeatedly, knives of pain stabbing at her guts, trembling like someone possessed by an evil spirit, while her defeated husband sobs at her bedside like a child.

In his letters, Flaubert talks about how strongly he identified with his heroine as he wrote this scene of her struggle and death, saying that he had felt some of the painful symptoms she experienced in his own body, so much so that he, too, began to vomit. Perhaps he intended for this scene to be very affecting, and perhaps he completely succeeded in this; doubtless there are many who have shed tears while reading it. And yet I, however, felt nothing but indifference toward Emma’s dreams and affairs, her disappointments and miseries and suicide. During my first read of the novel, I had been bored, but upon the next six or seven readings, the poison of Flaubert’s prose was already flowing in my veins. It was a drug that leeched me of all feeling, numbing me to the plot, to Emma, to her lovers and her poor husband, leaving me unmoved by anything but the beauty of the language.

This is not to say that Flaubert’s language is a form of empty lyrical construction, a flow of ornate, flowery phrases and expressions that roll on ceaselessly while managing to say nothing at all. On the contrary: his prose is somewhat austere, meticulously precise, objective — at times almost scientific; in perfect harmony with the subject it is treating, so much so that I wasn’t even aware of it on my second reading. But little by little it seeped into the core of my being, until finally one day I felt a sudden, icy chill.

It is a language that turns everything it touches into ice, freezing it in place. As though Flaubert were indeed writing about a frozen world, a world in the aftermath of an ice storm, transformed into a glacial landscape, where every spark of life has been extinguished, leaving behind only silent ice sculptures with which I couldn’t empathize, whose emotions I was unable to inhabit: it was enough to look at them from afar, astonished at their cold glitter.

I knew then that this was the way I wanted to write, that this was the style I longed to emulate, one that, to me — rightly or wrongly — seemed to embody Flaubert’s rancor toward life, his desire to embalm it within his sentences. And I realized then that I had another, real, motive to write, which went beyond dreams of fame and glory: to flee life, to avoid having to inhabit it, to freeze any emotions it might move in me within the cold prison of words.

I have always been one of those people who tries to keep a stranglehold on his emotions in every way possible: withdrawing into myself, keeping my social relationships to the tightest circle I can manage. I love routine; I shun anything new or unexpected. I drink to excess; I minimize the importance of anything I might feel if it so happens that I feel anything at all. But most of all I try simply not to feel, as though I never came equipped with emotions in the first place. In Flaubert’s person, in his theory, his working method and his language, I perhaps saw not only a justification for continuing to live this way, but implicit evidence that I could take this way of life and elevate it, through writing, into an art form.

And so, I began writing with some form of regularity: several times a week I would sit before my computer screen, trying to write short stories in French, which, before deciding to work seriously on my Arabic, was the only language I mastered. At the end of my work day — more or less five hours long — I would take account of my stockpile of sentences and whisper them aloud to myself (not daring to raise my voice any higher, the way Flaubert did), marvelling at their musicality.

But it wasn’t long before I started to realize that my stern master had wormed his way inside my head. There was a perpetual scowl on his face, his features contorted into a stony mask, disapproving of everything I wrote. This word is not “exact;” find another. That word appears twice on the same page, replace it with a synonym. That alliteration is an abomination to the ears. This expression is the worst sort of cliché, the sentence is clunky, the whole paragraph doesn’t hold together and has no organic connection to the one that follows… Frankly, I don’t know if what you’re writing is even worth revising.

Until every word I typed on the keyboard became a sort of self-inflicted torture. Confronted with an infinite number of possible words, from which I had to choose only a single one, and with all the possible sentences that could be composed from those words, and convinced that there was only one word that could be the “exact” word, and one formulation of that collection of words that could compose the “exact” sentence, I was felled by anguish.

The pace of my output kept slowing down, until at last it rivaled Flaubert’s (though it goes without saying that there was no comparison in terms of quality). Writing was reduced to an agonizing search for words, then a mind-numbing attempt to identify their ideal sequence within the sentences, and then how to best organize those sentences into paragraphs, etcetera, a process of sheer rumination that bore no relation to anything outside the realm of pure language, that is, to life itself. To this day, I only know how to write like this: like a jester, inexpertly juggling words, fumbling one and then having all the others fall on his head.

I sit before my computer — as I am doing now, trying to finish this essay that has so far taken twenty-five days scattered over a period of three months to write, that is, about 150 hours — staring at the blankness of the virtual page. I do nothing but wait for the sentences to arrive, which arrive only in drips and drops, and between one drop and the next, there is an eternity of suffocating tedium, which has ironically become my only armor against agony.

But then, every so often, it happens that as I blunder about, trying to grab for the words, they do not slip out of my grasp, they do not collapse upon my head; instead they line up of their own accord into a fine and exquisite sentence. And I feel the blood flowing into my veins, and I feel that there is something in this sentence that surpasses words and language, something of the external world around me, something that resembles life, but isn’t life exactly. I become aware then, that writing is a way of cramming and compressing life into words, and that, like a monk, a hermit, I am willing to sacrifice all worldly pleasures so long as I can come alive within the space of a sentence.

Necesito hablar con la persona que escribió este artículo. Hiló las palabras de la manera más bella, y no pude parar de leer hasta el final.

He took Arsenic in view of primary and possibly Secondary syphilis( Sexually Transmitted Disease.) Julian Barnes analysed the evidence in his meta-novel, “ F’s parrot.”He was never married. Had a few girlfriends. Was he azoospermia victim?

No matter how incompetent md bovarys husband was as a dr. He was educated in the properties of opium and absinthe. Dr Bovary could have eased his wife’s death and did not. Why?