Karim Goury

Five years after The Nile Hilton Incident (2017), Tarik Saleh takes us once again to Cairo, to the heart of the greatest Sunni institution in Egypt and the Muslim world: Al-Azhar. Through the eyes of Adam, a simple fisherman’s son who has just been admitted to study at the famous Islamic university, we will experience his journey of initiation, which will prove to be quite different from our idea of Quranic studies. Tarik Saleh invites us to experience a story full of violence and tension.

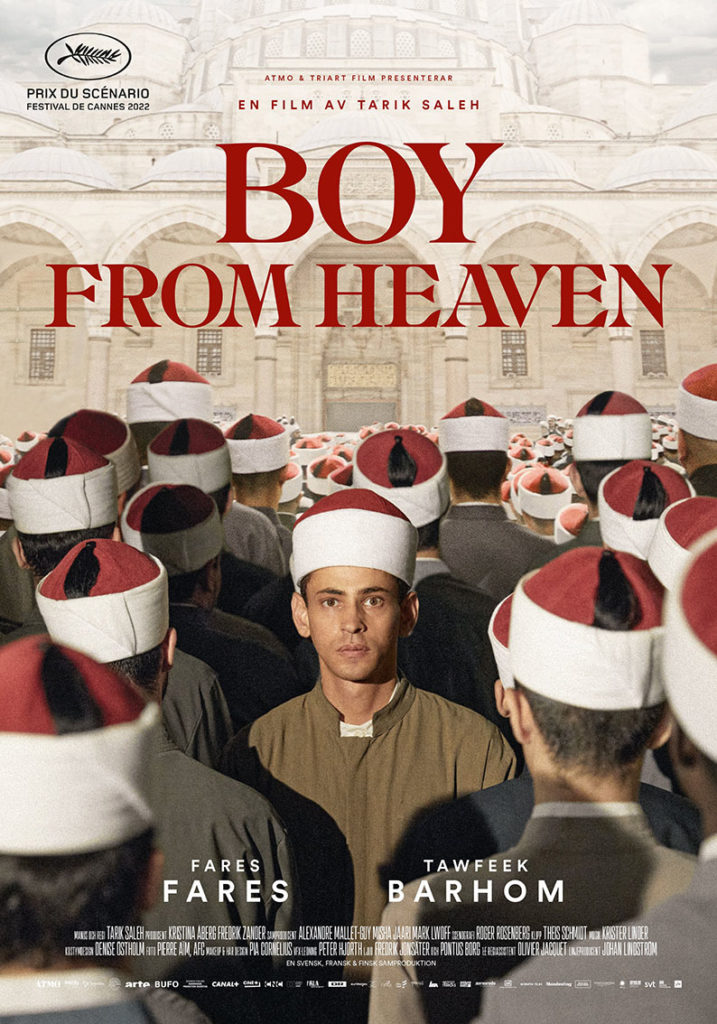

Served by two excellent actors (among others) — Fares Fares (already perfect in The Nile Hilton Incident) and Tawfeek Barhom — the film unfolds a relentlessly suspenseful plot (the screenplay won an award at the Cannes Film Festival 2022), worthy of the great spy films — infiltration, betrayal, blackmail, threats, influence peddling…

Pious and naive, Adam arrives in Cairo directly from his native countryside, obviously for the very first time. All his young life, he has had to lend a hand to his father (a courageous fisherman and uncompromising father of three boys), to whom he has not even announced his admission to Al-Azhar for fear of his brutality, as much as for the guilt of abandoning him. His mother is dead, making Boy From Heaven an (almost) exclusively male film.

As soon as Adam arrives in the religious lair, the vise tightens inexorably around him. One senses very quickly the doctrines that clash, the power struggles that oppose the sheikhs. These antagonisms are exacerbated by the (natural) death of the Grand Imam, who must be replaced by a vote of the sheikhs of the institution.

Adjacent to the religious power, but with an invisible hold on it, is the political power — which is never far away in Egypt. Men in a secret meeting at the State Security headquarters decide to interfere in the election of the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar. A candidate close to power is nominated by the direct representative of President Al Sissi (omnipresent in his portraits that line the streets of Cairo) and his supporters, who are represented as a secret cabal with full power over Egyptian civil, religious and military society.

One expects that the film will draw up an indictment of the current corrupt Egyptian regime, and that is its strength, but you have to wonder about the conditions of production, in view of the censorship and the pressures to which the director had to be subjected. We know that the director, of Swedish nationality, is persona non grata in Egypt since The Nile Hilton Incident and that Boy From Heaven was shot in the Süleymaniye mosque in Istanbul. However, Saleh refuses to accuse anyone, as it is true that it is a whole system of corruption that he denounces, and by the end of the film it’s no longer clear who in the system are the masters and who are the pawns. This subtle reversal of positions allows the film to question the viewer in a more personal, almost philosophical register. What responsibility does the place we occupy give us? What choices do we have to make? And what are the consequences? Politically, Tarik Saleh makes cinematographic choices. Or the opposite. It is through cinema that he answers his political questions.

But back to the story. Adam’s apprenticeship began away from all the sordid and obscure maneuvers, both religious and political. The young man’s faith and naivety make him a model student, promised a bright future as a sheikh. But a murder within the university itself will brutally upset his destiny. The murdered student was a government spy. Just before he died, he felt in danger and decided to stop. He managed to appoint Adam to take his place as a mole for State Security without Adam knowing it.

From then on, Adam is caught up in a mechanism in which he can’t see the gears, but little by little, he guesses some of the advantages and all the dangers. Manipulated by various and sundry others, the young man becomes at the same time a pawn and a rook in this political-religious chess game.

Boy From Heaven is a hyper-realistic film. It takes us into a secret, fascinating and necessarily fantasized universe. Here in Europe (I write from France) the Arab-Muslim world is a mystery for most people, largely unknown in its institutional functioning. And for the rest of the world, it can seem frightening. It’s not that Saleh’s view really reassures us about the sanity of this world, but in any case, it opens its doors to us. That’s already a lot for those who are unfamiliar with it. The film certainly has a documentary scope. From the second sequence, we understand that Adam had no chance of escaping the destiny that his father (and Egyptian society) assigned to him, but that he managed to change what seemed to be written by hard work, guided by the sheikh of his village. His admission to prestigious Al-Azhar University is a grail that allows him to dream of a better material life, but also to accomplish a religious identity that becomes symbolically at least as important as acquiring more material status.

The cinematic tragedy here is the purity of Adam’s desire on the verge of realization, shattered by the corruption, injustice and arbitrariness that enclose Egypt, prohibit possibilities, and suffocate its entire society. For Adam, the dream is impossible and turns into a nightmare. Immersed in the subjective world of the young Egyptian, we are as powerless as he is in the face of the implacable machine ready to swallow us up.

The tragedy is also in the police authority incarnated by Colonel Ibrahim. Fares Fares delivers a strong and subtle performance. Physically, he is the opposite of Major Noredin Mostafa in Saleh’s previous film. His gray hair is shaggy and sparse, his eyes are magnified by corrective lenses, giving him the look of a beaten old dog, and his baggy clothes suggest the silhouette of a civil servant without stature. He stands hunched over, as if tired, weighed down by the inertia and heaviness of the power he embodies. His position is supposed to be intimidating but his appearance inspires only pity and contempt. Finally, we would like to see in this character the premonitory incarnation of a regime at the end of its breath, which self-destructs and asphyxiates itself by its own perversion.

In comparison, the youth embodied by Tawfeek Barhom as Adam is the exact opposite of Fares Fares’. His vital force, even when caught in situations whose violence he could never have imagined, and his strength of character, are the personification of an Egyptian youth called to take his destiny in hand. And we (re)think of the Arab Spring that shook Egypt and the Arab world, powered by its youth, more than 10 years ago now. We wonder why this revolution didn’t take its course and succeed — this is how Adam inspires us in the film. A young novice, he is like a reed. He may bend, but he does not break.

Never in the film does Adam seem totally overwhelmed by what happens to him. He faces events with courage and self-sacrifice. His adaptability is immense. At each danger that confronts him, it is as if he is presented with the choice of good or evil. Each decision he makes brings him closer to the final judgment. He continues to advance and we advance with him. But at no time does the power over him succeed in making him abdicate his faith. Such is the inevitable failure and blindness of all authoritarianism.

The ending of Boy From Heaven is a brilliant idea in terms of both script and direction. Rather than a spectacular turn of events, a classic Deus Ex Machina (and I use this expression deliberately!), the dénouement of the film corresponds exactly to the end of the training of young Adam, as if the two paths were merged and did not exist without each other.

Saleh achieves a cinematic coup de force here: he offers his main character the fulfilment of his destiny as a man of faith through the very resolution of the plot of this exceptional spy film.

What a thorough and excellent review, making one crave to see this film. Thank you, Karim.