Can Egypt’s Arab Spring heal a rift between a sister who has been abused and a sister who doesn’t believe her?

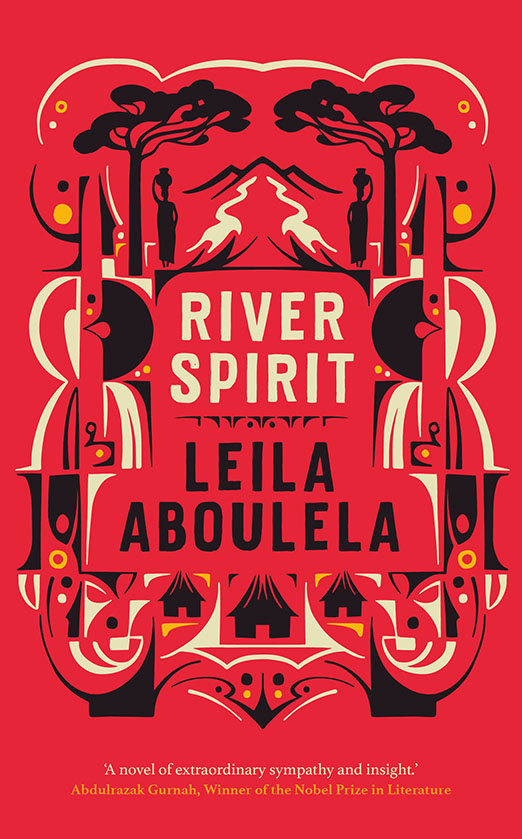

Leila Aboulela

Tante Walaa was my sister’s mother-in-law. In a roundabout way she was family and I could not wriggle away from her. She was a widow with two sons; the eldest, Amer, was married to my sister Dunia and the younger, Shadi, was still in school, struggling with his coursework. I was asked to tutor him in physics but I said no. It wasn’t only because Tante Walaa had no intention to pay me. It was because I knew Shadi was a weak student and, to be honest, I couldn’t be bothered. When I said I was too busy to give private lessons Dunia looked at me with silent reproach and Amer asked, more annoyed than curious, “Busy with what?” I just ignored him. Tante Walaa, on the other hand, kept pretending that sometime soon I was going to get round to helping Shadi with his GCSE physics. She would call me and seeing her name on the screen, I wouldn’t pick up. She left messages using my nickname and saying that she missed me. “You’re a naughty girl, dodging me,” she’d say. “But I know that you love us and want the best for Shadi.”

One day I found myself alone in her flat. By alone, I meant in her company without Dunia or Amer. It was like I needed them to justify my connection to her or act as go-betweens. Tante Walaa lived in a flat above them and I had been there before, joining in family meals where the table was overladen with food that was varied but not especially tasty. On that afternoon it was winter, the sky threatening rain and in the streets men covered their mouths with woolen scarves which made their eyes look even more sullen.

It happened like this. First, I was visiting Dunia and she said we should go out to eat. I would rather have stayed in the warmth but she insisted. “I can’t imprison myself at home waiting for the repairman, I need to live my life.” Telephone in hand, she’d been threatening and pleading with the shop where she had bought her dishwasher. Two nights earlier, it flooded the floor with dirty water. Since then an electrician was meant to visit but so far he hadn’t shown up and Dunia was becoming frustrated, afraid to use the dishwasher and make another mess.

As we stepped out into the landing, she said, “I need to nip upstairs to Tante Walaa and leave her my key in case he finally does show up. Then I will tell the doorman to send him up to her.” I could have waited while Dunia ran upstairs with the key or I could have gone down to the street without her. But she said, “Come with me to say a quick hello to Tante Walaa.” I groaned out loud but she pulled my arm. I figured it would be rude to refuse to go up. It would look as if I hated her mother-in-law. “We’ll be quick,” she reassured me. “We won’t even have to go in.”

My sister bounded up ahead of me. The staircase was dark and smelt of garbage. Dunia was flexible and strong. At least in comparison to me. I had a handicap that was slight enough to go almost unnoticed; it was a secret that only doctors, Dunia and our late parents knew about. I kept it close to myself and didn’t talk about it. I was holding down a job that many would consider good. What else did people want from me? Tante Walaa opened the door of her flat and was happy to see me. “Come in, Nada. You must come in,” she repeated while Dunia made up excuses and held out the key of her flat explaining about the repairman on his way to fix the dishwasher.

Suddenly we heard him below us, dropping his toolbox on the floor and ringing the bell. Dunia dashed downstairs, calling out to him that she was on her way. “Come in,” Tante Walaa was beaming at me. “You can’t stand in the doorway like that.”

Her flat was the exact layout as Amer and Dunia’s except that everything in theirs was brand new and hers was like stepping into the past. There was a complicated reason why she hadn’t swapped flats with Amer and Dunia so as to climb fewer stairs. I had heard it once and it made perfect sense at the time but now I couldn’t remember. There was no elevator in the building and she struggled with or without shopping. I stepped into her sitting room. It was full of formal, heavy furniture, over-sized sofas that only guests sat on and an elaborate, large dining table. In summary, ugly.

The dining table was laden with plastic bags, disjointed objects and what looked like bric-a-brac. “I’m selling all this for charity,” she explained. “I’m helping a widowed mother. Here have a look!”

She seated me at the dining table and began to show me the things. “That’s nice,” I said fingering a prayer set with embroidery around the edges.

“It’s for you,” she said, bundling the set into a plastic bag and shoving it towards me. She named a high price. I started to tell her that I already had one but she cut me off.

“For charity,” she said, her nose shining. “We have to help those less fortunate than us. Don’t we? I feel so sorry for this lady. She has a son who needs private tutors on top of the school fees. So expensive. Look at this. What do you think?” She held out a brass candleholder.

“I never light candles,” I said.

“But you’re helping someone and getting something pretty too.” She placed it on top of the prayer set. “And here’s a lovely pair of pajamas.” They weren’t lovely. They were in a ghastly shade of green. “Try them on. Go on. I am quite alone. There is no one here. Or go change in the bathroom if you like.”

“No need.” I mumbled.

She was already walking away towards the kitchen. I knew she was going to bring me a drink or sweets. I should have stopped her and insisted that I needed to go down to Dunia. To be with her while the repairman dealt with the dishwasher.

Tante Walaa came out of the kitchen with a can of Miranda and a glass on a tray. “I’m glad the pajamas are your size,” she said as if the matter was settled.

“Look,” I protested. “I don’t want the pajamas or anything.”

“Why not? It’s not as if you can’t afford them.” There was a sting in her voice.

“Where did you get all these things from?” I asked her.

“They’re brand new,” she said as if taking offense. “Don’t think they’re second hand or anything like that! Would I be cheating you?” Her voice rose, “That poor widow has an older son but he’s married now. His flat is full of brand new things. And that’s not easy, that’s a strain so she doesn’t like to impose on him and ask for money. He does help her from time to time, but his focus is on his new wife now. It’s natural I suppose. Can’t blame him.”

I nodded. A widow with two sons, the older newly married and the younger in school. What a coincidence! But surely she wouldn’t be so blatant. Or would she?

“Look, this is really special.” With pride, she lifted up a box. There was a saucepan inside it. “It’s no ordinary saucepan. You plug it into the wall and it cooks everything extremely slowly. Perfect for you. While you’re at work, it does all the cooking.” She named a price.

“Impossible.” I stood up and started heading towards the door.

She grabbed my shoulder and her voice rose. “Don’t turn me down. For the soul of you mother. For her dear soul. You will not turn me down.” Her grip on my shoulder tightened, like it wasn’t friendly any more. She almost pushed me so that I was sitting down at the dining table again. “Nada, be reasonable now. Consider the money you are spending as a mercy towards your mother.”

It upset me that she mentioned my mother. I remembered the first time she collapsed, and I took her to hospital. They wouldn’t even examine her until we paid straight up. The way they treated us — it was as if we weren’t human. I was only in my second year at university and my bankcard didn’t have enough on it.

Tante Walaa was going on and on about the slow cooker. We started to haggle over the price. Back and forth. I pushed. I went through the motions but she was tough and it wasn’t as if I were in a shop. I felt restricted. At the end of the day she was family so there were certain lines I couldn’t cross. She went on praising the cooker. “When you come home, there’ll be a freshly cooked warm meal waiting for you. I know you work hard. This is exactly what you need.”

I explained in detail why I wouldn’t use it. It was as if I hadn’t spoken. She dashed into the kitchen again determined to bring me all the other accessories that came with the cooker. I walked over to the window. High identical buildings, painted grey with pollution, crammed with people and their junk. The washing lines were heavy with winter clothes, puffy dressing gowns and men’s pajamas. Dirt stuck to everything, even to the leaves of the trees. Down in the street, a little girl with uncombed hair was rummaging through the trash. She wore a jumper, but no socks, her dirty feet in plastic slippers. Cold, poor and unschooled. Yet she could hurt me if she needed to and, given half a chance, steal my handbag. She would tell lies and use filthy swear words.

When I turned away from the window, the vision in my left eye was blurred. I could see properly only to one side so I tipped my head and scrunched up my nose. In the gilded mirror above the settee, my face looked pale and stretched. Tante Walaa looked solid and happy. “These things could be for your trousseau, Nada. Yes, why not? Soon you too will find a bridegroom. Nowadays young men want a strong earner like you. It’s hard times not like in the old days. Believe me, they will overlook other things.” My legs felt heavy and my feet too small as if I were a boxing stand. When punched I would sway but never ever fall over. I started to answer her but something in the way she said that last bit about overlooking faults made me stop.

It went on and on. She was sure I needed a garish painting, a set of mugs, a handbag and a linen set. I suddenly had this strange detached feeling that I was waiting for her to reach a level of satisfaction, only then would she let me get out of here. I wanted her satiated but her appetite was strong. When the cash in my handbag wasn’t enough, she made me sign receipts that added up to a whole month’s salary. I felt a sweeping down pressure inside my stomach. She looked triumphant and I felt sick.

The walk down the dark staircase to Dunia’s flat was even more blurred. Amer was now with her. I stood in front of them in the living room, the splashing sound of the now functioning dishwasher in the background. They were not a romantic couple; I could never pick up a sexual charge between them or a thick longing. Not like it had been with Dunia’s ex-boyfriend, Emad. They had been passionately in love but Dunia wanted everything perfect. When she caught him out once — no, not with another woman — but walking into a psychiatrist’s office, she dumped him. Then picked Amer up. He was flattered and grateful at the beginning but over time, and especially after our father’s death, Amer was hardening. I had never heard him and Dunia talk about anything except their flat and its contents, about shopping deals and prices. They were life partners and not lovers; they were colleagues not mates. You’d think they were in the same business together, the project of setting up, stocking and maintaining a new flat.

They exclaimed over my purchases but did not seem to need much explanation; it was as if they already understood. I complained about my migraine. Dunia gave me Valium and I headed straight for their guest room. I had stayed over with them many times and the room was familiar. I lay down on the bed and dozed. I know it sounds over the top and most likely it was a scene from a film I’ve watched, but I dreamt that I was toiling away in the building of a pyramid. Around me the other slaves were being whipped and shouted at. When one of them collapsed to the ground, the rock he had been carrying rolled towards me, to crush me and no one could stop it because everyone else was struggling with their lot.

Dunia and Amer were talking about me. Perhaps they did not feel the need to whisper. Amer said, “Serves her right for refusing to tutor Shadi. It’s not as if she doesn’t know how much private lessons will cost!” I sat up in order to listen but only Amer’s words were clear. Dunia’s tone of voice sounded like she was defending me. He replied, “She’s sorted with that computer job of hers. No one hit her on her hand.” He meant I wasn’t forced into buying anything. He said, “Your beloved sister earns more than me,” as if it was all my fault. Dunia’s whine made me frightened. I guessed that she had aggravated him by criticizing his mother.

The medicine made me doze until I felt her cool hand on my forehead, her voice gentle with concern. After our mother passed away, Dunia started mothering me. I looked up to her and always asked her advice. Today she was wearing her checkered coat, the one we bought together at the sales. “I have to go to my shift now, Nada. Don’t get up till you’re well enough to drive. Promise me. Wait till I come back and we can eat together. Or you can even spend the night. Yes, that would be best.”

I woke up to his voice. It sounded reproachful and mocking. Amer was sitting close to me on the side of the bed. He tugged my ear in a playful way but it was painful and his voice was mean. “Why did you buy too many things? Throwing money around like a millionaire, then you have the nerve to complain! Speak. Speak up.” His finger was now below my chin, jerking my jaw upwards. “Look at me! Speak. Don’t you have a tongue?” I ground my teeth together. If I let them go slack, my teeth would rattle. I moved my head away and tried to sit up. He pushed me down. He smelt of cigarettes and his leather jacket. I started to kick and shout. But women shouted up and down this building all the time, no one paid any attention.

The more I fought him, the stronger he became. “You have the nerve to blame my mother! How dare you. She’s better than you. A hundred times over. Say it! Say, she’s better than me.” His other hand was now inside in my hair, the fingers pressed into my skull. He tilted my head back as if I were at the dentist and my mouth forced open ready for the cold pain. “Don’t. Please don’t.”

He yanked at my hair, “You have to repeat it. You have to say it in a loud voice.”

“She is better than me,” I whispered.

“A hundred times over. Say it.”

“A hundred times over.”

He smiled. “Good. You should go out of your way to please her. That’s how it should be.”

“Let me go.” With all my energy, I pushed him away. “Get away from me.”

He stood up but his hand still jabbed at my forehead tipping it back. “What’s all the fuss about? Do you think I’m going to rape you? In your dreams. I’m not even attracted to you. No man would be.” He looked down at my thigh as if he could see through my jeans. “Dunia said it’s the ugliest piece of skin she’d ever seen in her life. It gave her nightmares.” I gasped at the shock. She had told him; she had actually told him.

I was already in the car, cold fingers round the steering wheel, when he came down carrying my things. He tossed them in the back seat as if this was a normal day and he was helping me with my shopping. My heart sank when he said he needed to go back upstairs and get the rest of the things, they were that many! I should have opened the boot for him and tidied things up. But I felt safe in the driver’s seat, belt locked and the engine running. When I drove off, the back seat was littered and piled with stuff I neither needed nor liked.

The migraine made the drive home feel weird, the city uglier than ever. Not the City Victorious but the City Oppressor. I drove through damp muddy streets, other cars pressed against me, their drivers hating me. A few drops of rain fell on the windshield, wiping it left streaks of dirt. I passed the City of the Dead, those houses that looked like houses but were empty if you passed through the tall metal gates. No buildings, no pyramids, just wrapped dead bodies under the ground, without earth surrounding them, scattered in a room to become sacks of bones.

The medicine made me slow, and all the things around closer than they usually were. Stopping at the traffic light, I heard pounding. Someone was trying to smash the back window. I started to shout and even beeped my horn to scare them off. Instead, one of them used a stick and the glass shattered. A hand reached inside and grabbed at the plastic bags piled on the seat. Another pair of thin arms covered in dirty and faded flowery material were hauling what they could, lifting out then reaching in again. The light changed, I pressed the accelerator and heard her scream. “You broke it, you bitch.” Later in every nightmare I would hear the bone crack.

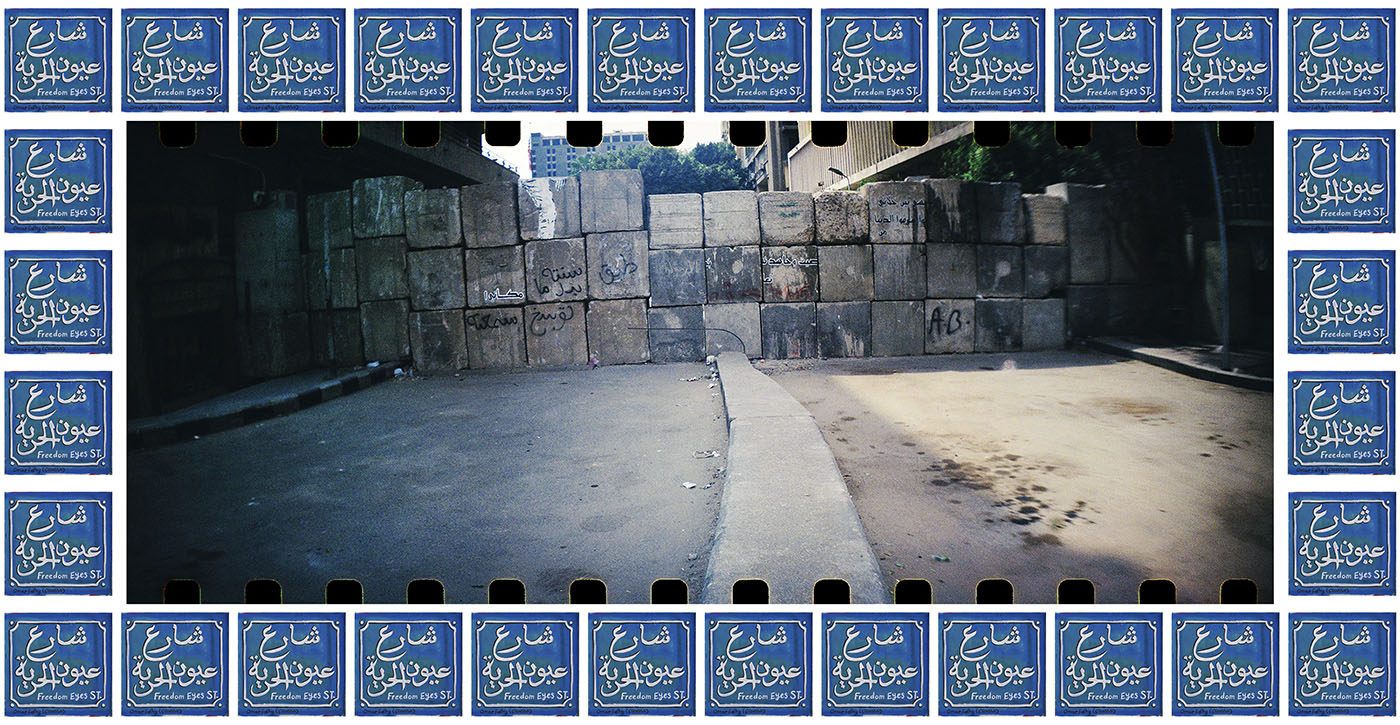

This was what the city’s billboards were saying, the meanings hidden behind conventional words. This was the graffiti on the walls. The hieroglyphs on stone. This was the city’s survival tactics, its street wisdom and rules. More visceral than poetry, deeper than propaganda. What I read, what I heard, what was taught, what was known. Lie when you are in a tight spot / It is normal to hate the weak. It is their fault that they are weak. The weak need protection. They will pay for it with money and labor or obedience and loyalty, they will pay with it with their honor. Complexity is superior to simplicity / Underestimating or overestimating are serious mistakes / Every single encounter is a power struggle / Underline your accomplishments. Boast of your success. Otherwise someone else will take all the credit.

Dunia and I had always been close. I was furious that she had shared my secret. Years ago, our parents had told us not to speak of it. They did not want me to be pitied or looked at with disgust. A fourth-degree burn caused by a childhood accident. When it healed it looked like a large flat navel on my inner thigh. I got used to it; I stopped thinking about it. At the beach I wore leggings under my swimsuit, and everyone thought I was being modest. I could have had plastic surgery, but my parents said no need, too much expense, thank God it’s not her face. Would she find a husband? Sure, “all women are alike in the dark.”

Amer denied that he had even entered the guest room let alone touched me. Lie when you are in a tight spot. He claimed that I was accusing him of rape (I never did) due to my “sick imagination” and “state of deprivation as an unmarried woman.” In a flash, he became the injured party and I, the jealous younger sister, the warped homewrecker. When I reached out to Dunia she snubbed me; when I phoned, she didn’t pick up.

I took my car to the dealer to get the smashed window fixed. The mechanic I spoke to said he was too busy to get the work done within an hour, it would have to wait. Until when? He just shrugged his shoulders. He looked at me with complete disinterest as if he was too world-weary and important to deal with my request. A 20-pound note would get him moving and he would take it in broad daylight even though the office of his superior with its glass windows was just behind him. After what happened with Tante Walaa, I was in no position to part with more money. So, there I was in the garage arguing and pleading, when a man walked out of the office and called my name. I didn’t recognize him at first — glasses instead of contact lenses, hair slightly longer. He turned out to be Emad, Dunia’s ex, the one she had dumped after finding out that he was getting psychiatric treatment. Emad said he was working for his father now. I hadn’t known that the garage belonged to his father. He turned to the mechanic who was already standing straighter. “What’s the car needing?” The mechanic replied that fixing the window was simple and he could get it done within an hour. Every encounter is a power struggle.

“Why don’t you come and wait inside,” Emad said.

Normally I would have said no thanks, hopped into a taxi and killed the time at Dunia’s. My only other option now was to wander around and find a coffee shop with good Wi-Fi. It was cold and miserable, so I accepted Emad’s invitation. Besides, seeing me on friendly terms with the owner’s son, the mechanic was bound to get my window fixed in the shortest possible time.

Emad’s office was protected from the draft and he ordered me a hot drink. We exchanged small talk but didn’t mention Dunia. He expressed his condolences for the death of our mother. We shared memories of her. I sipped my drink and started to relax. A woman walked in. She was visibly pregnant. What startled me was how uninhibited she was. “Come with me to the demonstration,” she said to Emad. I remembered the video that was doing the rounds on social media. Meet in the square on Tuesday, enough is enough with this government, let’s make a change.

Her name was Sally. I immediately sent a text to Dunia. “You won’t believe who I’m with now? Emad’s wife.” Underline your accomplishments. Boast of your success. Dunia was bound to be interested in her ex. And we could slip back to how we were, our stupid quarrel forgotten.

Sally was different than Dunia — especially in looks, hair all naturally frizzy and wearing dungarees. But there is no need to describe her because the whole world got to know her. She was the one in the news photo that spread from Washington to Kuala Lumpur. The pregnant woman standing up to the snarling soldier, her belly between them, her unborn baby inches away from his gun. Sally the icon of the revolution, the face of the Arab Spring. That taunt bulging stomach thrust out against the brutality. Innocence and hope leading the rebellion, coming smack up against the vicious army. But that came later. As did all the praise — Our Revolution is a Mother. We’re sacrificing for our unborn children. Fearless Sally… And then the condemnation and envy — But how could she expose her unborn child to the teargas… How could she be so careless… What kind of mother-to-be is that … For God’s sake the battleground is no place for a six-months-old fetus. To be honest, Emad said this last sentence to her too but in gentle tones, more timid than assertive, nothing like the venom poured on her on social media. But the photo and all that it brought was still in the future. On that afternoon when my car window was getting fixed, she was still a stranger to me. I witnessed the exchange between her and Emad. Sally, insistent that he shut down the garage for the day and let his employees go to the protest.

I kept glancing at my phone waiting for Dunia to answer my text. Instead of feeling awkward, I was captivated by the discussion between Emad and Sally. “I have my father to think of,” he said. “I am not my own man.”

“Yes, you are. I’m sure of it,” she said, with the kind of confidence that was contagious.

I got to know them well after that, indeed it was with Sally that I went to my very first protest. She was a natural leader; there was a charisma about her and an ancient fearlessness which that famous photo later captured. “My new friends,” I sent a selfie of the three of us to the silent Dunia but instead of the grudging but affectionate reply I expected, she wrote, “I can’t believe you can be so inconsiderate.”

I phoned and she did not reply. I rang the bell of her flat and she didn’t open though I knew she was inside. Surely, she would soften. Surely, she would be missing me by now. Overestimating is a serious error.

No longer seeing her or going over to her place, I suddenly had plenty of time on my hands and a lot of bewilderment. Emad and Sally took me in or at least partially filled the gap. Sally wanted another listener, another follower. Emad was happy to make her happy. I had never been greatly interested in activism. My knowledge of local and international politics was shaky. But now when Sally spoke about power and injustice, I understood.

Things got to the point with Dunia where I was desperate enough to appeal to Tante Walaa. I dragged myself up the stairs. Shadi opened the door for me. I hadn’t seen him for quite some time. He had shot up and now had a new wisp of a moustache. Behind him the dining table was empty. He looked at me as if he didn’t know who I was. It occurred to me that everything was his fault. Or rather my fault for refusing to tutor him. One “no” had let lose all this animosity and lost me my sister. Underestimating is a serious mistake.

“How’s the physics going, Shadi?” I couldn’t help myself.

Tante Walaa appearance saved him the trouble of answering. She didn’t invite me to sit. “How dare you!” she shouted. “After all we’ve done for you.”

What had they done for me? I couldn’t remember any favors.

“Dunia took care of you after your parents died. She put up with your defect. And in return you want to wreck her home! Your heart is black. Do you think I would welcome you after what you said about my son! He was decisive. He said, ‘Dunia, it’s either me or your sister, choose.’ And here you are playing dumb. A speciality with you. So, let me tell it to you straight. Don’t you dare step into my home again. This whole building is forbidden to you.”

I left but not before abusing both her sons. The elder for being a bully and the younger for being a lazy student. “I hope to God he fails physics,” I said but as I spoke, I realized that it was easy to turn on those who were younger. It is normal to hate the weak. It is their fault that they are weak. My new friends had made me aware that this was cowardly. I took a deep breath and faced the one who was older than me, the one who had more power. “You’re a liar,” I said to Tante Walaa. “Pretending to sell all this junk for charity when you were keeping all the money for yourself.”

Months passed when I neither met Dunia nor spoke to her on the phone.

I missed her so much that I sometimes wanted to apologize to her and Amer, even though I was the one wronged. They were the only family I had. When I heard Sally talking about how in police cells and secret prisons people were confessing to crimes they hadn’t committed, I understood. I could imagine that you only had to squeeze someone hard enough and repeat the lie over and over again. Then they would name names and — without the need to invent for it would be spelt out for them — they would tell their interrogators everything they wanted to hear.

The city erupted. Individually, collectively, in clusters and in groups people took to the streets and protested. For years, some people had been demonstrating against the government, but no one took them seriously. My parents thought of them as troublemakers. That January and February it was different. The protests built up momentum, people at work were leaving early, or weren’t showing up at all. One afternoon I was the only one under-thirty still at my desk. As always, the work absorbed me but I felt left out. The protests were where it was all happening, the square was the place to be.

When the government shut down the internet, Sally called and asked for my help. “You are a computer whiz,” she said. “Come over and help.” I didn’t hesitate. It was a challenge after all and as I drove away from the office, I had all sorts of ideas on how to bypass the regular access and get round the shutdown. Within the hour I was with a group of computer engineers and programmers like myself. Try this and that; be creative, go on and not give up. For several hours, I was so absorbed that I almost forgot why we were doing this. Maybe for the others getting back the internet was a means to an end but for me it became the ultimate achievement. Eventually we pulled it off. We managed to find a way to circumvent the shutoff by going back to old-fashioned dial-up. The breakthrough was pure joy. I almost cried. After that there was no going back. The revolution was not an abstract concept, I was in the thick of it, a hacker, someone who had taken part!

We marched to the square and though, at first, I felt self-conscious, the mood took a hold of me. Here was a place where I could never be lonely, where I didn’t feel helpless and I didn’t feel handicapped. Demanding change, urging each other to be proud. “Raise your head up high,” we chanted. “You are more honorable than the one who trampled you.” The sit-in started; the tents set up. Portable toilets, vendors selling snacks, rotas for meals and for standing guard. Such good will, such purity of intention. Street art. A concert, talks, Friday prayers, Coptic Mass, bride and groom in all their wedding finery, sandwiches and tea. In the square at night, around a small fire in a brazier, I started to believe in a change that would put everything to rights.

Photos, even that famous one of Sally, don’t tell the whole story. What we heard, what we felt in the streets. The acrid constant fear, the heat, the beat of a drum, the hubbub of voices, a high pitch of a woman calling out, the low rustle of wind through the trees, the sudden loud din and tinny echo of a microphone getting started. Sweaty palms and hoarse throats. The exhilaration of being all together, anger coalesced, a cry against injustice and fear, and later collective grief.

When we sang the national anthem tears ran down my face. Love was the flag swaying, love for this homeland with all its shame and damning faults, this city with its new alien ugliness, the desert and river that pulsed the span of our lives.

Voice messages to Dunia … I might die any day here and you are my flesh and blood … How can you be so hard-hearted … When I see Emad with Sally I know that you married the wrong man … Get out of this marriage, Dunia, you deserve better … Her reply eventually came, her voice … Can’t you see that you are making things worse? Putting me in an impossible situation …

Day after day, I carried cartons of water to the protestors in the square, I carried medical supplies and blankets. At times people referred to me as “Sally’s friend” and I glowed. When I got tired, which often happened sooner than I wanted, I would sit down and upload material on social media. I would write to Dunia and say to her, “Here is where you need to be.” Around me others were carrying Molotov cocktails in Pepsi crates. They crouched behind metal barriers they had ripped up from the petrol station.

One night I saw her, Dunia. It must be her; it must be. I shoved my laptop in my bag and stood up. Suddenly it was as if everyone was shouting orders. The dreaded sound was either rubber bullets or stones beating against the lampposts and the tents. Through the gas and smoke, I could still see Dunia’s checkered coat. I hobbled up to her, the tears streaming down my face. I wanted a hug. My sister was here because she understood. Everything would be alright between us like it was before. Dunia turned to face me. “Run,” she screamed. The security forces were firing birdshot. I looked behind me and we started to run from the truncheons and the thugs.

I love the way the abrupt ending brings all the strands together. Congratulations, Leila

The story cleverly weaved a number of issues and scenes. Very enjoyable reading.

An absorbing tale of a troubled family relationship set against the growing discontent on the streets of Cairo.