Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik

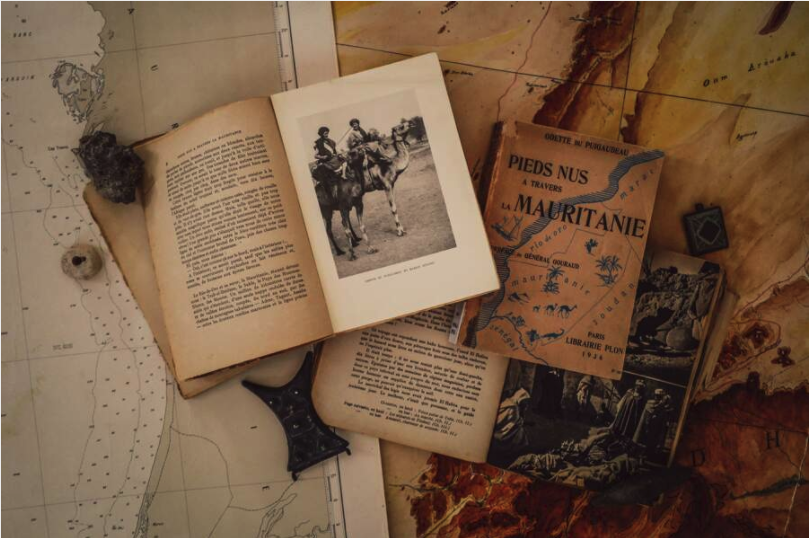

In the opening paragraphs of La Route de l’Ouest (The Road West), published in 1945, French colonial explorer Odette du Puigaudeau (1894-1991) attempted to explain to her readers why she and her partner, Marion Sénones (1886-1977), chose to travel to Mauritania in 1933 from Paris. “Why did we choose this bit of the Sahara, barely pacified, these 850,000 square kilometers of sand and rock, with no water, when there are so many beautiful countries where life is easy and pleasant?” Puigaudeau queried. Precisely because, she explained, they were not in search of a pleasant or even an easy life, but instead yearned for a “primitive life, with its risks, its struggles, and its total austerity.”[1]

What drew the two women to Mauritania was the prospect of a culture shock. Life in Paris was not always easy for these two queer women and they imagined the Sahara as a large austere expanse in which to reinvent themselves — a space in which to finally find their life purpose. In Mauritania they did indeed find their calling: they became colonial ethnographers, carefully gathering written and drawn data on the peoples of Mauritania, which they relayed back to the French government and various other “scientific” institutes in Paris. Puigaudeau and Sénones’ archive of ethnographic work is one of the few sources available to historians on Mauritania of the 1930s. In fact, one hairdresser in Nouakchott uses Puigaudeau’s Arts et Coutumes des Maures to reproduce early 20th-century Moorish hairstyles, which she claims she would never had known had it not been for this book.[2] The problem is that books like Arts et Coutumes des Maures perpetuate the colonial imaginary and have determined our aesthetic understanding of Mauritania for generations to come. As such, a historical intervention is necessary to ensure that these archival pictures and drawings are appreciated not only for their beauty and artistic value, but also for their role in perpetuating the colonial system and its understanding of non-European peoples.

While Puigaudeau and Sénones have influenced the popular imaginary of Mauritania in France and Europe, they figure very little in the scholarship on French exploration of the Sahara, not for the lack of archival sources, but perhaps because they do not fit into the traditional narrative of colonial motherhood.[3] Their archives, housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, include dozens of boxes of letters, administrative documents, pictures, travel diaries, published works, and hundreds of drawings. Puigaudeau, in particular, produced countless articles and nearly a dozen books. Other than a couple as-of-yet unpublished dissertations, the only scholarship on Puigaudeau is archivist Monique Vérité’s intimate biography, Odette du Puigaudeau: une Bretonne au desert, published in 1992.[4] Though Verité conducted extensive archival research to write the biography, her close friendship with Puigaudeau gives her work the quality of a hagiography more than that of a work of historical inquiry.

In 2020, journalists Catherine Faye and Marine Sanclamente published L’Année des deux dames. The book documents the two French journalists’ travel across Mauritania in Puigaudeau and Sénones’ footsteps. The book is a celebration of Puigaudeau and Sénone as queer and feminist icons. “They loved each other and didn’t fit into any boxes,” write the two journalists in L’Année des deux dames. “They left everything to live as they wanted, without the pressures of society.”[5] While Faye and Sanclamente make note of Puigaudeau and Sénones’ racialization of Moorish society, they choose to nonetheless admire the two colonial women, despite, and perhaps because, of all their contradictions. In the end, these contradictions are presented as one more quirky facet of these two lesbian desert-lovers’ personalities, rather than as an expression of their colonial and racial logic.

Both Verité’s work, Une Bretonne au desert, and Sanclamente and Faye’s book, L’Année des deux dames, present Puigaudeau and Sénones as subverting the colonial power. Verité stresses that “when Odette du Puigaudeau realized that the colonial regime cemented its superiority, engendered exploitation, dispossession, and ruin she became an anti-colonialist.”[6] But a critical reading of Puigaudeau’s travel journals, and of her ethnological work on Mauritania, reveals the many ways in which the two women’s relative marginality in the metropole served in fact to buttress the colonial regime. Puigaudeau fled Paris and through this escape she became one more peripatetic European for whom the desert (as any other place considered hostile and devoid of inhabitants) represented an antidote for social marginalization, “a haven whose façade of social liberation was underwritten by colonial subjugation.”[7] Her social marginalization in Europe pushed her towards Mauritania. Through her travel journals, which attracted much attention in Europe, and through presentations in conferences across France, Puigaudeau promoted a space for those who felt marginal in Europe to find a spot within the colonial infrastructure — one that took into account their marginality, their desires to subvert gender roles, while still garnering the admiration and support of the French state and of its citizens. Even as Puigaudeau criticized the French colonial regime in Mauritania, she gathered, catalogued, and fixed Mauritania’s cultures for the French to consume in museums and magazines. In the end, her travels across Mauritania renewed her social standing in Europe by giving her a scientific caché amongst the Parisian colonial and intellectual elite.

Puigaudeau’s ethnographic legacy remains to this day. One rainy Sunday in July 2021, I travelled to Le Croisic, the town where Odette was born. The town, with the help of the woman who has become Puigaudeau’s official biographer, Monique Vérité, had organized an exhibit to pay tribute to this most “surprising of residents.”[8] The exhibit, entitled “Odette du Puigaudeau: Une Bretonne au désert — invitation au voyage,” showcased Puigaudeau and Sénones’ artwork in particular, dozens of portraits of Mauritanian men and women, almost all unnamed because the two women did not think to record their names. One expository panel introduced the visitor to Mauritania and to the country’s history, exclusively as it related to the French presence in Mauritania and the Sahara. Puigaudeau and Sénones newfound popularity, as demonstrated by the recent publication of L’Année des deux dames and by this exhibit, is part of a larger popular movement to resuscitate women from the annals of history. However, in the process of giving voice to these “voyageuses intrépides,” scholars must realize that they are participating in the silencing of Mauritanian voices. Puigaudeau and Sénones were obsessed with the idea of Mauritania — a fixed idea of a “primitive” life in harmony with the desert and its hardships — this is the idea that they conveyed through their drawings and photographs.

I am in the very early stages of writing a graphic history based on Odette du Puigaudeau and Marion Sénone’s relationship to Mauritania. I will use the sources created by Puigaudeau and Sénones, but unlike others, I will mine the archive for silences and recast a history of Mauritania that does not perpetuate colonial power and render colonized bodies invisible. A historical graphic novel is the perfect media to do this. I hope to collaborate with Mauritanian artist Amy Sow to create the graphic novel, in an effort not to replicate the colonial aesthetic. The historical narrative will exclusively be based in Mauritania, and be written from the perspective of one of Puigaudeau and Sénones’ guides. With this graphic novel project I hope to begin to decolonize the archive and existing scholarship and to recover Mauritanian voices of the 1930s and ‘40s.

Notes

-

[1] Odette du Puigaudeau, La Route de l ‘Ouest (Maroc-Mauritanie), (Paris : Editions J. Susse, 1945), 13.

-

[2] Catherine Faye and Marine Sanclemente, L’année des deux dames, (Paris : Éditions Paulsen, 2020), 296.

-

[3] See French historian and Jesuit Missionary Jean-Baptiste Piolet in 1900 on the the role of the “femme coloniale” or “la coloniale” [Jean-Baptiste Piolet, La France hors de France: notre émigration, sa nécessité, ses conditions, (Paris: F. Alcan, 1900).]

-

[4] The two dissertations I’ve found so far are : Georgy Khabarovskiy “Savoir-vivre féminin et faire-savoir colonial dans les récits de voyages féminins de l’entre-deux-guerres, » PhD Dissertation, Indiana University, 2018 ; Jeanne Sébastien, « Des chameaux et des hommes : le voyage d’Odette du Puigaudeau en Mauritanie (1933-1961) » PhD Dissertation, École Nationales des Chartes, 2019.

-

[5] Catherine Faye and Marine Sanclemente, L’année des deux dames, (Paris : Éditions Paulsen, 2020), 136.

-

[6] Ibid, 179.

-

[7] Julia Clancy-Smith, ““The Passionate Nomad” Reconsidered,” in Nupur Chaudhuri (ed.), Western Women and Imperialism: Complicity and Resistance, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), 64.

-

[8] “Odette du Puigaudeau: Une Bretonne au désert – invitation au voyage,” Le Croisic, France.