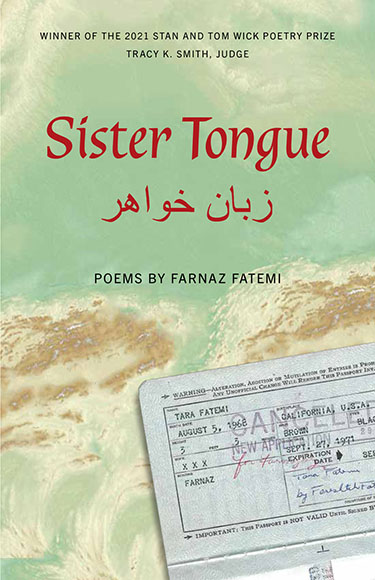

Farnaz Fatemi

The poems in Sister Tongue explore negative spaces—the distance between twin sisters, between lovers, between Farsi and English, between the poet’s upbringing in California and her family in Iran. This space between vibrates with loss and longing, arcing with tension. Fatemi’s poetry delves into the intricacies of the relational space between people, the depth of ancestral roots, and the visceral memories that shimmer beyond the reach of words.

Language is one of the origins of the poet’s displacement and the evidence of her non-belonging—in both Farsi- and English-speaking communities. The long lyric essay which makes up the spine of this book plumbs years of wordlessness and a journey of reconciliation, as Fatemi asks how her tongue might be a passport to the otherwise inaccessible territories within a self.

The poems in Sister Tongue metabolize longing while holding space for the poet’s multiple inheritances, offering a vision of a porosity of self. Through the work of this reckoning, Fatemi reveals how connections between people and places might be forged.

Untranslated

In the silence of my girlhood, spoons

clattered in glasses of tea.

The squeak of the front door closing.

I was the child

I’d never have. I listened for clues.

I spoke without saying a thing.

I made sounds to fill

the spaces I could see

around everyone. My teeth and eyes

gleamed, face open, a flower.

As if to say to these people,

Speak. Say things I understand.

Their untranslated words whoosh by,

an autumn gust.

Staticky din of English and Farsi

with afternoon fruit and cookies,

my lips mouthing along with them

to pay attention, as I wrote their stories

in my head, rearranged the letters

into meaning. I heard the squished sounds

of a heartbeat in a stethoscope,

pump and thrum.

In the languages

of women I could have been

I felt both lonely and contained.

We were chador-less,

light-skinned. All the women

who disappeared into the silence inside me,

I pull from the roar of the past.

I make introductions. By which I mean,

I want the foreigner in me

to meet the foreigner in me.

When I Kneel, I Don’t Think of a God

I think of you, and you, and also you,

so long gone, now, I’m not telling your stories,

I don’t invoke you to explain laughter.

I have other beloveds nearby

I watch to learn how to live,

close to the tip of my tongue, like you were.

You do not linger out loud.

You are not in my mouth.

But it’s not what you think. Now—

like the idiom I’d only heard, but never

bit into, couldn’t have swallowed—

you are in my liver. No, you are my liver.

That’s what I can say, when I pray:

jigar-e-man, my liver,

teach me what to do now.