What two new books tell us about the war on the Palestinian people.

Perfect Victims and the politics of appeal by Mohammed El-Kurd

Haymarket February 2025

ISBN 9798888903179

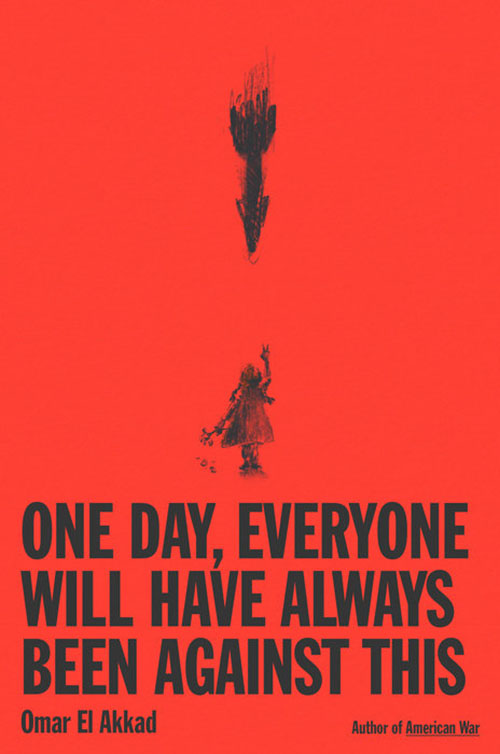

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This by Omar El Akkad

Penguin Random House February 2025

ISBN 9780593804148

Rebecca Ruth Gould

Since the beginning of the Gaza Genocide in October 2023, dehumanizing rhetoric against Palestinians has surged, particularly in the metropolises that are most directly implicated in the genocide. In the immediate aftermath of the al-Aqsa Flood operation, Israeli officials began referring to the Palestinians of Gaza as “human animals.” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pointedly contrasted the “children of darkness” of Palestine to Israel’s supposedly superior “children of light” — the same people who have perpetrated genocide. Everywhere in the media, we are met with subtle — and sometimes not so subtle — insinuations that Palestinians matter less than other humans, if indeed they are humans at all.

Against this onslaught of dehumanizing rhetoric, well-meaning objectors to genocide often resort to assertions of Palestinians’ humanity, sometimes by separating out the militants from the civilians, or the women and children from the men. Writing as a poet as much as a polemicist in his stunning nonfiction debut, Perfect Victims: And the Politics of Appeal, Palestinian writer and activist Mohammed El-Kurd alerts us to the dangers inherent in catering to this rhetoric of humanization. Another book published this month, the impassioned political memoir of Egyptian-Canadian writer Omar El Akkad, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, echoes El-Kurd’s critique of the political discourse that uses the rhetoric of victimization to whitewash or complicity in genocide.

The two authors approach their subjects from different mental locations and with different personal histories. For El-Kurd, growing up in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of Jerusalem while it was being taken over by settlers from Brooklyn has framed how he sees the world. He skillfully weaves his personal experience into the text. El Akkad’s sheltered childhood in the UAE and coming of age in Canada also mark his understanding of how the world’s resources are unevenly distributed, causing some lives to be seen as grievable while others are denied this basic dignity. Both critiques are relentless, and do not spare anyone, including themselves.

Even when well-intentioned, the rhetoric of humanization desensitizes us to the violence it describes. While this rhetoric can be used by those who see themselves as allies of the Palestinian cause, El-Kurd argues that it perpetuates dehumanization in another guise. “Humanization,” in his view, “restricts the range of sentiments and emotions we are permitted to express openly, the values, ideologies, and affiliations we can claim without retribution.” Operating through intense surveillance, the project of humanization “searches in our thoughts and fantasies, in our inferred intentions and ignorances, and in our tacit beliefs for attributes to censor and reeducate.” Its primary targets are those who fall outside the mainstream, whether through their skin color, gender, age, identity, or place of birth.

Both humanization and dehumanization assume that Palestinians must prove themselves in order for their lives to be valued, and to have a legitimate claim against genocide. Used in this way, humanization is racist: it does not take a people’s humanity for granted, as a simple fact of birth that can never be rescinded. Proponents of humanization make their case for Palestinians as if in an inverted court of law, in which the defender is guilty until proven innocent. El-Kurd suggests they attempt to prove Palestinian humanity by virtue of their “proximity to innocence: whiteness, civility, wealth, compromise, collaboration, nonalignment, nonviolence, helplessness, futurelessness.”

“Human” is Not an Adjective

Yet, “human,” as El-Kurd insists, “is not an adjective,” and “it is certainly not a compliment.” “Human” is not something that you get to be called when you are good; it is simply what you are by birth. It is inalienable, and even deeper than a right. “Human” is a noun, and it permits no reduction in its status. Either you are human in your core, and no one can take that from you, not even yourself, or you are not, and no amount of placating those in power will ever persuade them that you are. The contingent humanity that liberalism grants to Palestinians is one El-Kurd categorically rejects.

El-Kurd recounts his introduction to what he calls “the politics of appeal” in 2013, when he was a 14-year-old boy writing an open letter to President Obama. In the initial draft he wrote for The Guardian, he said: “Mr. President, we want our houses back. And our pre-1948 land.” So shocking was this child’s insistence on the return of his pre-1948 land that The Guardian editors almost refused to publish the letter. El-Kurd stood his ground. He resisted the pressure of journalists to adjust his speech to make it acceptable to a pro-Israel audience. He learned to refuse to be a “perfect victim” and not to accommodate racists.

The toxic and racist interplay between dehumanization and humanization generates the “perfect victims” complex that is the object of El-Kurd’s critique. Within this framework, Palestinians who fail to pass muster, whether due to their perceived embrace of violence, their (entirely understandable) refusal to forgive their murderers, or any other character trait that is perceived as non-ideal, become yet another justification for their people’s genocide. Rejecting these compromises entailed in the process of “humanization,” El-Kurd exposes its limits as a political strategy for Palestinian liberation. Humanization is used to reinforce a “politics of appeal” that hopes, against all the evidence, that “magically, marvelously, the Palestinian can finally escape the circumscribed category of the terrorist and find refuge in the even narrower node of victimhood.”

The problem with this hope is that it is never fulfilled. Considering it a fool’s errand, El-Kurd aptly cites the advice of the Muslim jurist al-Shafi’i: “If the fool speaks, do not answer.” For El-Kurd, the project of humanizing Palestinians reinforces their dehumanization without offering an equitable alternative to the genocidal logic of dehumanization.

One day the social currency of liberalism will accept as legal tender the suffering of those they previously smothered in silence, turned away from in disgust as one does carrion on the roadside. Far enough gone, the systemic murder of a people will become safe enough to fit on a lawn sign. There’s always room on a liberal’s lawn. —Omar El Akkad

Dehumanization and the War on Terror

The critique of liberalism in a time of genocide is broadly applied to the post-9/11 War on Terror by El Akkad. Although a journalist by training, El Akkad is best known for his novels American War (2017), a futuristic fable of a disease-ravaged United States in the throes of a climate catastrophe, and What Strange Paradise (2021) which documents the plight of a Syrian immigrant facing deportation. El Akkad’s nonfiction debut, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, was, like Perfect Victims, written in the wake of the Gaza genocide. While El-Kurd and El Akkad are both trying to make sense of the evisceration of Gaza, their different locations within the imperial core generate different techniques to make their points. Both are creative artists, but we see the poet rise to the surface in the experimental format of Perfect Victims, while El Akkad’s approach is that of the storyteller and novelist, at home in narrative form.

One Day is partly a critique of the forever war mentality of post-9/11 America and partly a political memoir of growing up as an Egyptian immigrant in Canada whose work as a journalist led him to track the targets of US imperial ambitions around the world. El Akkad wants to understand how states manufacture consent for genocide. He tracks the process through which consent for the Gaza genocide has been manufactured by mainstream media and the state while pointing to familiar echoes from the past: in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Much of what El Akkad learned about these machinations happened while he was a journalist in US-occupied Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay. His analytical framework, provided by the War on Terror and US imperial hegemony, enables him to draw vital connections between what is happening in Gaza and what has happened in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. While it broadens his lens beyond Palestine, this framework arguably prevents El Akkad from grappling with the specific brutality of Israel’s occupation of Palestine and thereby providing essential context for the Gaza genocide.

As a storyteller, El Akkad develops a narrative that explains the use that liberal states have made of the discourse of humanization during the past quarter-century. When they invented a War on Terror, the leaders of the western world revived a well-established colonial strategy. Waging wars for the sake of “the greater good,” these leaders asked their electorate to suspend their belief in a shared humanity and to instead accept that Iraqis, Palestinians, Afghans, or whomever was being targeted and treated as the collateral damage of war, were no longer human.

The Critique of Liberalism and its Limits

El Akkad’s skill as a critic is apparent in his memorable definition of liberalism as “something at its core transactional, centered on the magnanimous, enlightened image of the self and the dissonant belief that empathizing with the plight of the faraway oppressed is compatible with benefiting from the systems that oppress them.” El Akkad describes in excruciating detail the process whereby children of empire — a category that includes myself as well as him — learn “to hold two contradictory thoughts simultaneously.” The first is the belief, in which I was schooled throughout my childhood in the US, that “one’s nation behaves in keeping with the scrappy righteousness of the underdog.” In direct contradiction to this core tenant is the second, an “unspoken understanding that, in reality, the most powerful nation in human history is no underdog.”

El Akkad is an astute critic of liberalism. His talent as a creative writer is everywhere on display, particularly in the movement between his italicized passages documenting genocide and the pedestrian prose recounting his professional formation as a reporter in conflict zones. He is less effective when it comes to offering an alternative to the liberal framework or in enabling us to see outside its constricted world view. He is at his most acute when he documents that temporal gap that so often attends the recognition of genocide by the world. As he notes, when genocides are being perpetrated, governments typically go to great lengths to avoid using the term, “because usage is attached to obligation.” El Akkad speaks for millions of us when he writes that the experience of watching “the leader of the most powerful nation on earth endorse and finance a genocide prompts not a passing kind of disgust or anger, but a severance.” Like El Akkad, El-Kurd observes that the Gaza genocide marks a watershed moment in the history of the US’s image of itself as the benefactor of the world.

El Akkad’s analysis of the self-serving duplicities and hypocrisies of North American liberalism entirely resonate with my experience of growing up in Californian suburbia during the 1980s and 1990s, under Reagan, the first Bush, and Clinton. During these years, the Camp David Accords that had been brokered by Jimmy Carter in 1978 and the Oslo Accords presided over by Clinton served as proof that the US was a force for good in the world. Our textbooks taught us that Thanksgiving commemorates the amity between the white pilgrims and the native peoples, and that the US was leading the way in creating a two-state solution for Israel-Palestine (always with Israel coming first). I grew up with these clichés. I was schooled and tested in them. I only later learned to recognize them as lies.

Yet when I showed El Akkad’s scintillating passages of critique to a friend who was not a child of empire like myself, who was not fed the propaganda of US imperialism in his textbooks, he saw little truth in El Akkad’s words. What I read as a subtle critique resonated for him like a defense of liberalism. Perhaps this gap between my friend and myself defines the limits of what One Day says about Palestine: El Akkad is writing for those of us at the imperial core, who despise Biden, but hate Trump even more, whereas much of the world simply doesn’t care one way or the other. The era that believed in the benevolence of the US empire is over. In its wake, all those outside the imperial core see is deceit, including when it is packaged in the language of critique. In this sense, El-Kurd’s remit is broader, and more likely to outlast our present moment.

After the Politics of Appeal

Once our faith in the liberal order has been crushed, once we have been forced to reckon with the persistence of white supremacy in world politics, and every ideal that we relied on is exposed as hypocrisy, what remains? What viable political project persists in the wake of the Gaza genocide? What brave new world has a live-streamed genocide catapulted us into? What are we to do on the earth we inhabit now?

One thing we can do is turn to past histories of resistance and forge from them new legacies for the future. It is no accident that El-Kurd’s rejection of the politics of appeal is heavily indebted to a long tradition of African and African American revolutionaries, among them Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Huey Newton. Often, El-Kurd creatively paraphrases their words, making them relevant to the Palestinian struggle. The very texture and style of his writing reveals the striking relevance that the African American struggle for equality has for Palestinian liberation. Taken together with the Palestinian poets and creative writers invoked by El-Kurd, often in his own translations, such as Ghassan Kanafani, Rashid Hussein, and Taha Muhammad Ali, this tradition is formidable, and it cannot be eradicated, not even by genocide.

In 1932, a group of anticolonial Francophone surrealists published an extraordinary pamphlet entitled Murderous Humanitarianism. Although originally written in French, the pamphlet was only ever published in English in the translation of the famous Irish writer Samuel Beckett. Murderous Humanitarianism speaks to our political present, including to the genocide in Gaza. As a document signed by French surrealists André Breton and Paul Éluard as well as the Martiniquan Surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J. M. Monnerot, this pamphlet reveals the political relevance of poetics, as it was manifested then in Black Surrealism, and now in El-Kurd’s scintillating prose.

With a sharp polemical voice that echoes El-Kurd’s rejection of Palestinian victimhood, the surrealist poets denounce the “counterfeit liberalism” that confronted them at the dawn of a new fascist era. In 1932 as in 2025, war “receives fresh impulse under the name of ‘pacification.’” With El-Kurd, the poets recognize that we cannot retreat into the liberal promise of a more hopeful world order if we really aim to defeat “murderous humanitarianism.” A more radical approach is needed, one which entirely rejects “the Holy-Saint-faced International of hypocrites” that conjoins capitalism and the values of western civilization to fund genocide.

Finally, El-Kurd adds to the critique of liberal humanism another alternative, which may be his most lasting contribution of all: humor. As a response to genocide, the kind of irreverent humor El-Kurd celebrates and embodies in his prose may be the most effective weapon of all. He cites his grandmother’s statement that “If we don’t laugh, we cry” as an inspiration. Similarly to El-Kurd, my inspiration comes from a friend in Gaza who wrote to me, when I expressed surprise at the jokes he told me even as the bombs poured down on him, threatening to end his life: “Rebecca dear, I retain my sense of humor because it is an important part of maintaining my humanity.”

My Palestinian friend taught me that what El-Kurd also makes clear: humor is a powerful rejection of genocide because the joker is mocking the racism that calls on him to “prove” his humanity. Humor breaks down barriers between people in radically dissimilar locations, connecting them, not by transcending their differences, but by, El-Kurd says, implicating “the spectator in the spectacle,” and exposing us to “a world without pretenses where we look each other in the eye.” In this rare moment of reverence in a radically irreverent book, El-Kurd carves out a path for creating a world that resists the genocide of the Palestinian people.

May the Gaza genocide be the turning point for this generation. We don’t know what the future holds, but both El-Kurd and El Akkad show us that there is no turning back from what has been done with our funding, and even in our name. Breaking with the liberal order that produced this genocide is the only way forward, the only kind of humanism worthy of the name.