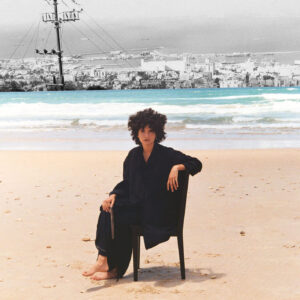

Brahim El Guabli

I am Amazigh, Black, and Sahrawi. Amazigh language is my mother tongue. My mother is Black, and my father is Sahrawi. The only picture I own of my maternal grandfather tells me that his roots run deep into sub-Saharan Africa. My category of Moroccan citizen has escaped the attention of scholarship on race and racism in North Africa and had been denied legal recognition until the reformed 2011 Constitution. This means that between 1956 and 2011, people straddling these diverse belongings were erased in favor of an Arab-Islamic identity that was shaped by unifying Jacobin-model Moroccan nationalists, adopted for the post-independence state in 1956. Both the school system and the media did a fabulous job of desensitizing generations of Moroccans against their Amazigh heritage and made sure that they were contained within the state-sanctioned identity of Morocco as an Arab and Muslim country.

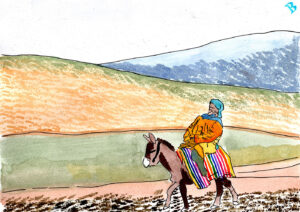

Coming of age, however, senior friends in high school taught me about the work of the Amazigh Cultural Movement (ACM), which helped me over the years to reclaim both my Amazighity and Blackness. Although Amazigh, which means both white and free people, and black are an oxymoron, they are co-constitutive of my story of origins. My Sahrawi roots, due to political issues that cannot be discussed with enough nuance and precision in a short article, remain a work in progress. Each of these identities is underlain by political decisions, stories, movements, memories, and also amnesias that affirm the complexity of talking about one’s origins. Origins cannot but be elusive in a space that has been a locus for migrations, mobility, and human miscegenation for millennia.

Aṣl (origin), uṣūl (origins), and laṣl (Amazigh for origin/origins) evoke several types of relationships to people and place. Our origins are the matrilineal or patrilineal relations we have with our parents who brought us into the world, thus determining our place in hierarchical systems and relationships within communities. Both my blackness and my Amazighity—my oxymoronic identity—are bequeathed to me by my mother. From my father I inherited a sense of nomadism and an unbounded curiosity about the world. He was one of the very rare bilingual people in my village. He spoke Darija (Moroccan Arabic) as if he did not know any Amazigh and vice-versa. Growing up in this Amazigh and biracial home, I was already different from the other children in my community, having origins that encompass blackness and “Sahrawiness.” Origins also connect us to place, thus giving us a sense of authenticity through an extended inhabitation of the land. Akāl (land in Amazigh) evokes rootedness in the place of origin. Whether used to reclaim a sense of being aït tmazirt (the rightful owners/citizens of the homeland) or tarwa n-tmazight (the children of the land), akāl has entrenched a strong connection between cultural consciousness and Amazigh indigeneity to the land of North Africa. Through the various conceptions of akāl and laṣl, one can make claims for revamp

ing the exclusive sociopolitical, juridical, and economic systems that have been put in place in North Africa. Tamṣlyt (indigeneity) has a rehabilitative power that allowed Imazighen to claim their akāl, and through the land a collective identity that state policies across the entire Maghreb have suppressed in search of an imaginary national unity.

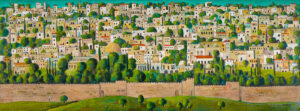

No wonder then that for Amazigh activists, awāl (language/speech in Amazigh), akāl, and afgān (person/people) are the tenets of Amazigh tamṣlyt (indigeneity) to North Africa. Tamazgha, which is the Amazigh activists re-Amazighized name for North Africa, extends from Siwa oisis in Egypt to the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean.[1] A reinvented homeland that provides Imazighen with an “imagined community,”[2] Tamazgha, a neologism, is the idyllic land of origins where Imazighen spoke the same language before the vicissitudes of time and recurrent conquests disconnected the different Amazigh populations and turned them into a minority within their own homeland. As a result of conquests, the markers of the land’s Amazighity were erased. Toponymies have been changed, Amazigh names were forbidden by North African states, and the Amazigh language and culture were folklorized. However, this remapping of North Africa through Tamazgha was not just a revolutionary act that reindigenizes the land, akāl, but also a transformative act of renaming that connects the land to its language of origin.

Of all Amazigh historians, Ali Sidqi Azaykou (b. Taroudant, 1942-2004) was the champion of the necessity to listen to the land, read the topography, and write its history based on the traces Imazighen left imprinted in the topography and its toponymy.[3] In Tamazgha, the land speaks Amazigh. Only when a land (akāl) tells its history in its own language (awāl) can one affirm that the indigenous populations have a say in the way their homeland is administered. Nonetheless, the usual definitions of indigeneity fail to capture the nuances of the situation in the Maghreb.

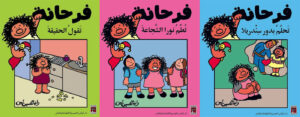

Generations of Amazigh children were the product of the state’s de-Amazighizing system. The school, which was usually a prefabricated two-unit building outside or in the middle of the village, became the space where the indigeneity of Amazigh children had to be sacrificed for the purposes of nation building. The school, this space where the teachers spoke a language that was different from the imam’s, was a barrier between the Amazigh world of real life, which we navigated in our Amazigh mother tongue, and another world that required knowledge of Arabic. Suddenly, the world of Arabic replaced the world of the mother tongue, and every bit of our Amazigh knowledge had to be rewritten and translated into Arabic, turning us into palimpsestic beings through the school system. Tafunāst (cow) became baqara, aghrūm (bread) became khubz, agḍīḍ (bird) became ṭā’ir, and tinml (school) became madrasa. Three years later, the same words become vache, pain, oiseau, and école, with the learning of French, widening the gap between the mother tongue and those of school. It was not just the use of words that changed, it is also the worlds that we inhabited as children that transformed. Every day, we straddled a world of orality with our mothers at home with another one of written sources at school. One world conveyed knowledge through verbal communication whereas the other used images, books, and didactic instruments to fashion our Moroccanness. Two worlds that fashioned our identities, bifurcated our tongues,[4] and complicated our sense of belonging.

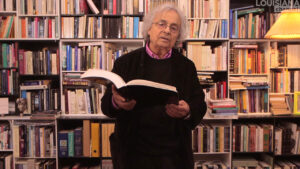

The Moroccan writer Abdelfattah Kilito has discussed in depth his shuttling between the language of home in the old medina in Rabat and the colonial school in the new city.[5] While the coordinates of the two worlds Kilito navigated were set by a colonial system, the post-independence world of Amazigh children were established by nationalists who saw Morocco as an Arab and Muslim nation. Similarly to Kilito, however, Amazigh children were Imazighen at home and Arab at school. Although we were villagers in a pre-Saharan village in the south of Morocco, we were taught that we were part of something larger called the Arab world and the Islamic ummah. Even though the school taught that “sukkān al-maghrib al-awwalūn hum al-barbar” (Berbers were the original inhabitants of Morocco),[6] the system was actively Arabizing our tongues. Today, mutatis mutandis, I can say that I have two mother tongues: Amazigh and Arabic. I am not a bi-langue in the Khatibian sense nor do I feel any contradiction between claiming my Amazigh indigeneity and considering Arabic my second mother tongue.

In his celebrated novel Amour bilingue—translated as Love in Two Languages—Moroccan novelist and essayist Abdelkébir Khatibi depicts the emotional and mental state of the bi-langue.[7] Different from the bilingual, bi-langue seems to describe a post-colonial being whose life is split between two competing languages. In Khatibi’s case, Arabic and French. The bi-langue in Khatibi’s novel lives in a state of permanent translation and uncertainty. This fascinating articulation of foreign language speaking as a pain-laden experience offers an opportunity to think about the relationship between language and suffering: how does one suffer in or because of language? But how could language be a source of a pain? In his Le monolinguisme de l’autre (Monolingualism of the Other),[8] Jacques Derrida suggests that the only language that he speaks is not his. An Arab Jew of Algerian provenance (he spent his first 18 years in Algeria, until 1949), Derrida lost both his Arabic and Hebrew, and, thanks to or because of republican education, he adopted French as his own language. However, when Vichy laws were implemented in Algeria, Derrida found himself outside school and outside French society to which his family adhered since Jews were given the French citizenship in 1870 as a result of the famous Decree Cremieux. In his reflection on his state during Vichy in Algiers, Derrida writes about his exclusion from school:

I was very young at the time, and I certainly did not understand very well what citizenship and loss of citizenship meant to say. But I do not doubt that exclusion—from the school reserved for young French citizens—could have a relationship to the disorder of identity which I was speaking to you about a moment ago. I do not doubt either that such “exclusions” come to leave their mark upon this belonging or non-belonging of language, this affiliation to language, this assignation to what is peacefully called language.[9]

While the bi-langue in Love in Two Languages suffers from an internal dissonance as a result of the clash of languages within herself, Derrida in this passage asks the disturbing question of suffering because of the political uses of language. Derrida uses the removal of his French citizenship, which lasted for two years, to ask “But who exactly possesses it [language]? And whom does it possess?”[10] Amazigh children were neither Khatibis nor Derridas, but they experienced the anxieties of language policy and its emotional consequences on them for not being able to convey the world in their awāl—the language of their origins.

The pain of language and the origins underlying it emerge when you discover that in the eyes of city youth in middle school that you are a Berber. Although our Amazigh language was academically subsumed by Arabic and French, which became our intellectual languages, Amazigh remained the language of home, hindering our total immersion in Darija. One could not use Amazigh to discuss scientific or academic topics without inserting French or Arabic words to help explain concepts that were never translated into Amazigh until that point in time. In the city, our mastery of Arabic without Darija enrooted us in our Amazigh aṣl because our urban peers called us shlūḥ, a derogatory term. Middle school became the source of most Amazigh students’ consciousness of their difference. Older and more engaged youth distributed Tifinagh (Amazigh alphabet) sheets and tracts about the ACM. By the middle of the 1990s, the ACM had already established itself as a strong and respected advocate for Imazighen’s rights, pushing King Hassan II in 1994 to announce the teaching of the language and its inclusion in the news.[11]

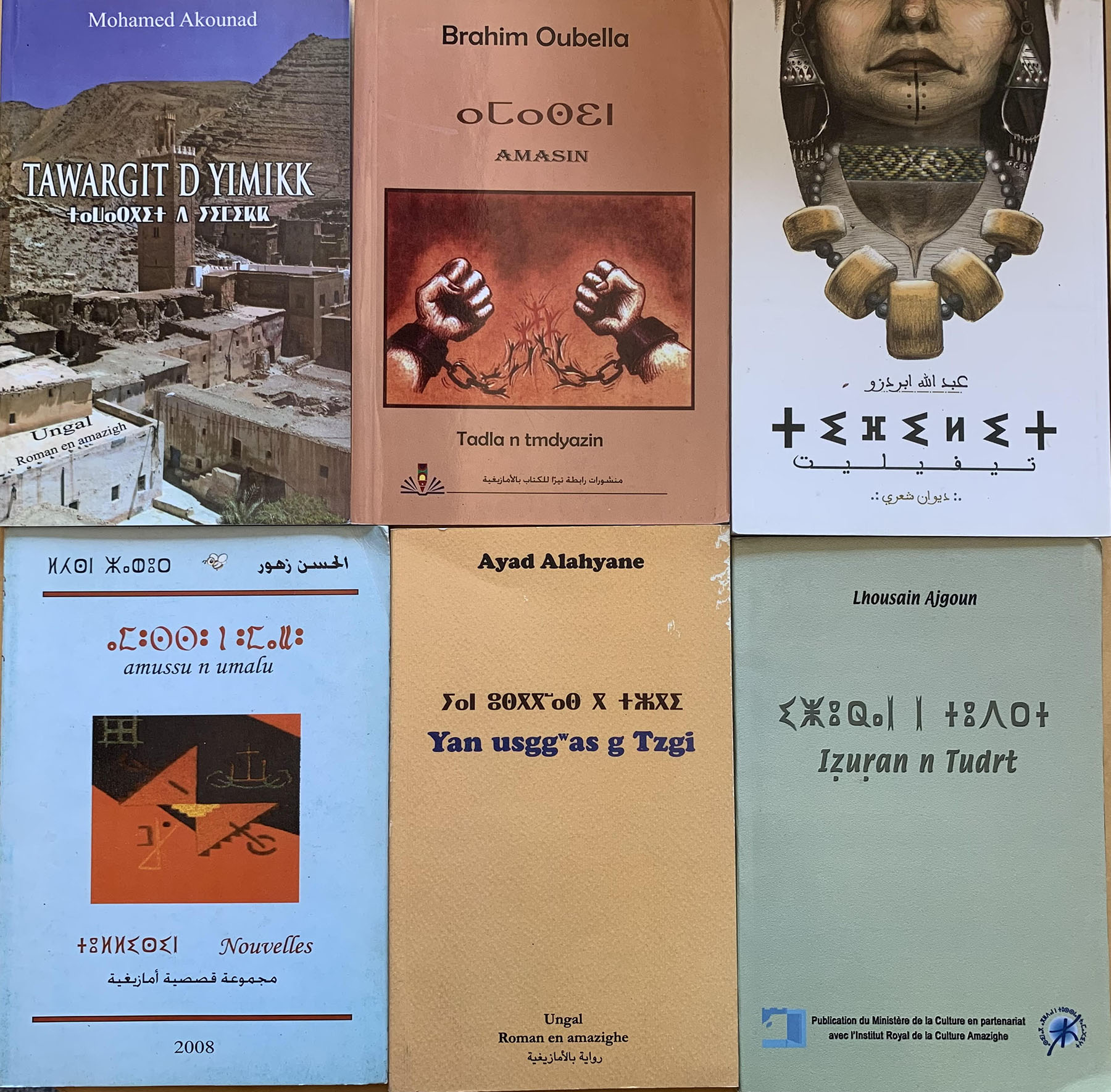

It was not, however, until 2002 that Amazigh language was included in primary school curricula. As a primary school teacher, I was among the first group of teachers who were trained in neo-Tifiangh—the version of Amazigh alphabet developed by the Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe (IRCAM). The teaching of Amazigh was, of course, preceded by the establishment of IRCAM in 2011. Part of a larger, albeit short-lived, project to democratize the country, IRCAM initiated the official recognition of Morocco’s Amazigh identity. In addition to its academic mission, IRCAM had a task to produce school curricula as well as audiovisual materials to disseminate the learning of Amazigh language and culture in Moroccan society.[12] Despite all the criticism leveled at IRCAM, it has managed to create very rich resources for Amazigh language and culture. IRCAM rehabilitated Tifinagh, published a significant number of studies about different aspects of Amazigh language and culture, and most importantly made Amazigh language part of the public sphere in Morocco. In a matter of twenty years, Amazigh language went from an oral status to having an alphabet that is taught and used throughout Morocco, creating a true plurilingual scene in the public area with its use in public signage. ACM in conjunction with IRCAM’s initiatives has re-Amazighized Morocco. The time when Amazigh language was silenced is over.

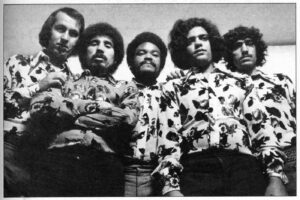

Music is a strong conveyor of Amazigh indigeneity. Musical indigeneity in Amazigh language operated in two contradictory ways. There is a search of origins through tradition, which is represented by the older generation of rwāys,[13] but there is also the search for indigeneity through musical innovation, like in the case of musical bands Izenzaren (Sun Rays) and Usmān (Lightening).[14] Rwāys—usually a coed band led by a main singer who played a one-stringed instrument called ribāb—created the earliest repertoire of Amazigh music. They usually steered away from the volatile topics of identity and politics, but their melodies and words created an Amazigh musical identity. The new bands that emerged in the 1970s reclaimed Amazigh indigeneity by either refiguring the rwāys’s repertoire, which is a very normal move, or by doing something even more radical, that is claiming Amazigh indigeneity through musical innovation in both melodies and instruments. It may sound contradictory to seek one’s roots through novelty, but the Amazigh cultural activists realized that wining back Amazigh youth who grew up in urban spaces Amazigh music had to do much more than just refurbish the old musical styles. This is where musical innovation meet with Amazigh indigeneity through the songs of Izenzaren and Usmān, who sang poems by Amazigh activists.

Those of us who lived in the hinterlands remember how difficult it was to capture the waves of the national radio at night when they aired Amazigh music. Some alleged that the weakness of the air waves was part of a political strategy to deprive Imazighen of taking pride of their music. Whatever the case may be, the days when the waves were clear for Amazigh music to reach the south of Morocco were happy days. Nevertheless, it was the video cassettes imported from Europe by Amazigh immigrants that gave this music global dimensions and contributed to entrenching it among Amazigh populations. The widespread use of VHS and DVD readers confirmed this trend. Starting in the 1990s, Amazigh cinema added another layer of complexity to Amazigh people’s relationship to their culture through the new media.[15] Boutfounast (The Owner of the Cow, 1992) was met with phenomenal success, paving the way for a more diverse and robust cinematographic industry in Amazigh. Seeing one’s marginalized language in film for the first time was not a negligeable event. It was a reflection of one’s existence and symbol of Imazighen’s resilience. Unlike Imazighen who came of age in the 1980s, younger generations of Imazighen are immersed in Amazigh cinema and its diverse corollary artistic and musical byproducts.

The Amazigh quest for origins cannot be complete without a detour via what I propose to call the “Amazigh Republic of Letters.”[16] This republic exists and straddles multiple geographic locations, extending from Tamazgha to West Africa and the Amazigh diasporas. The Amazigh Republic of letters is multilingual and transcontinental and is rooted in an Amazigh imaginary that harks back to a shared language and an ancestral land. Divided between literature written by Amazigh authors in other languages, such as Latin, Arabic, French, Dutch, and Spanish,[17] and literature written in Amazigh language,[18] Taskla Tamazight (Amazigh literature) has been one of the areas in which Tankra Tamazight (Amazigh awakening) took place in the last thirty years. A result of concerted civil society efforts and individual initiatives to enhance the writerly practices in a predominantly oral cultural production, these efforts paid off by creating a distinctly written Amazigh visual culture. Although this literary production is uneven between the different parts of Tamazgha, Tankra Tamazight has been embodied in a very rich production in ungal (novel) and tullist (short story) and iqṣidn (poems).[19]

Although there is nothing wrong with orality as a medium for transmission and restoration of a literary heritage, the struggle to write a language whose stigmatization was based on this very orality has turned written works into loci where Amazigh worldviews, myths, superstitions, and creative genius find their aesthetic expression. Writing has not superseded orality, however, although it allowed the Amazigh authors, who only publish in Amazigh, be it in Tifinagh or Arabic or Latin script, to engage in the intentional mining of language to ensure that the new Amazigh aesthetics that emerges from their work preserves both the language and the connection to the land. The Amazigh Republic of Letters is not just about circulation, it is most and foremost about recreating the cartography of the Amazigh land in North Africa and projecting the future preservation of the language in a rich written oeuvre.

As an Amazigh scholar who investigates memories and histories of erasure, I came to realize that an efficient way to use my Amazigh language skills and uphold my Amazighity is to study and teach my own cultural heritage. I find inspiration in the older generations of Amazigh activists who taught themselves Tifinagh and worked tirelessly to establish the contours of a powerful “Amazigh Republic of Ideas” whereby I mean an imaginary space for the emergence of the suppressed Amazigh subjectivity and agency through the reaffirmation of the connection between akal, awāl, and afgān. My current work is an investigation of the formation of the “Amazigh Republic of Ideas,” which I work to unravel in conjunction with thinking about the Amazigh Republic of Letters through the examination of Amazigh cultural production in several languages. It is edifying for me to read and write in my mother tongue, but it is even more exciting to use these skills to trace Amazigh etymologies in old books, read Amazigh literature in Tifinagh, and realize that the construction of indigeneity is a stupendous task that requires constant production of knowledge.

Studying Amazigh cultural production from the United States, where I live and work, reminds constantly of my duty as a native speaker of Amazigh language to draw on the rich resources we have in this country to unlock some of Amazigh culture’s vistas of knowledge for the benefit of my students and community. It is also my way to reclaim my indigeneity, albeit far from home.

Endnotes

[1] The concept of Tamazgha is new and has most likely emerged with the establishment of the Amazigh World Congress in 1995.

[2] I refer to Benedict Anderson ’s famous book Imagined Communities: Reflections On the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006).

[3] See Azāykū, Ṣidqī ʻAlī. Namādhij Min Asmāʼ Al-Aʻlām Al-Jughrāfīyah Wa-Al-Basharīyah Al-Maghribīyah (Rabat: al-Maʻhad al-Malakī lil-Thaqāfah al-Amāzīghīyah, Markaz al-Dirāsāt al-Tārīkhīyah wa-al-Bīʼīyah, 2004).

[4] Bifurcated tongues is inspired by Kilito’s “langue fourchue” in Je parle toutes les langues main en arabe (Paris: Actes Sud, 2013).

[5] Kilito, Je parle toutes les langues, 13-16.

[6] This sentence continues to feed controversies in Morocco. History and archaeology are still debated whether Imazighen came from Yemen—thus Arab—as this lesson taught Moroccan children. See ‘Abd al-Salām al-Shāmkh, “Iktishāf tāfūghālt yu‘īdu niqāsh ‘sukkān al-maghrib al-awwalūn’ ilā al-wājiha,” Hespress, accessed on September 10, 2021.

[7] Abdelkebir Khatibi. Amour Bilingue (Montpellier: Fata Morgana, 1983); Love In Two Languages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990).

[8] Jacques Derrida. Le Monolinguisme De L’autre, Ou, La Prothèse D’origine (Paris: Galilée, 1996) ; Monolingualism of the Other, Or, The Prosthesis of Origin (Stanford :Stanford University Press, 1998).

[9] Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other, 17.

[10] Derrida, Monolingualism of the Other, 17.

[11] Interested readers can check these resources: Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce. The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011); Paul Silverstein, “The pitfalls of Transnational Consciousness: Amazigh Activism as a Scalar Dilemma,” The Journal of North African Studies 18 (5) (2013), pp. 768-778; Brahim El Guabli, “(Re)invention of tradition, subversive memory, and Morocco’s re-Amazighization: From erasure of Imazighen to the performance of Tifinagh in public life.” Expressions Maghrebines 19 (1) (2020):143–68.

[12] See “ Texte du Dahir portant création de l’Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe,” IRCAM, accessed September 10, 2021, http://www.ircam.ma/?q=fr/node/4668.

[13] See Hassane Oudadene, Rways and Tirruyssa: A Symbolic Site of Amazigh Identity and Memory,” (forthcoming in a Jadaliyya special dossier on Amazigh cultural production coordinated by the author).

[14] To learn more about Usmān, see Tāriq al-Ma‘rūfī. Majmū ‘at usmān al-amāzīghīyya (Rabat: al-Maʻhad al-Malakī lil-Thaqāfah al-Amāzīghīyah, Markaz al-Dirāsāt al-Tārīkhīyah wa-al-Bīʼīyah, 2011) ; see also Brahim El Guabli, “Musicalizing Indigeneity: Tazenzart as a Locus for Amazigh Indigenous Consciousness,” in Nabil Boudraa and Karim Ouarras, eds., Idir: Views from North America (forthcoming).

[15] Brahim El Guabli, “L’fraja and Music in Amazigh Cinema,” INALCO conference “Le cinéma berbère et les autres medias,” March 30-31, 2021.

[16] This is a reference to Pascale Casanova’s notion in her book The World Republic of Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004; for more about the literary implications of this Amazigh republic of letters, see the author’s “Introduction” to the Arab Studies Journal’s special issue entitled “Where is the Maghreb? Theorizing a Liminal Space” (forthcoming in November).

[17] Mohand Akli Haddadou. Introduction à la littérature berbère suivi d’une Introduction à la littérature kabyle (Algiers : Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité, 2009), 7-33.

[18] Haddadou, Introduction à la littérature berbère,

[19] The author has curated seven articles about Amazigh literature and cinema that will be published in Jadaliyya as apart of a special dossier on Amazigh culture production.