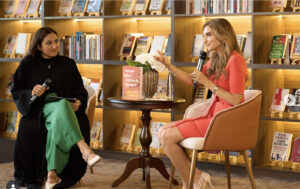

In this first personal account of a nuclear Arab family living in the diaspora, the writer recalls her nightly family dinners at a table laden with dishes from across the Middle East and reflects on what it taught her about her heritage, and how food was also a way for her to feed others a different narrative on a region plagued by negative misconceptions.

Layla Maghribi

Our nightly family dinners were at a fixed time known to all. Such was their unfailing consistency that on the odd occasion the house phone were to ring between six and seven in the evening, all five heads around the table would rise in unison, wondering “who could that possibly be?!”

My two older sisters and I sat with our parents around our family dining table for food and sustenance every night for most of our lives, well into adulthood and jobs and marriages and children. That rectangular table held our small nuclear family in the diaspora together and is where I learned about what it meant to be an Arab.

The soft power of food became the only acceptable show of force for people like us. Food was also a way for me to feed a different narrative of the region plagued by the unfair reputation that its only offerings are violence and refugees.

My mother was born and raised in Damascus, the capital of Syria — itself the de facto capital of Arab cuisine. The breadth of Syria’s epicurean talents is well known and revered across the region. From the stuffed courgettes to the cherry kebab to the many variations of kibbeh (with pumpkin, in yoghurt, fried, grilled, etc) Syria has seen many a mouth salivate over its exotic range of delicacies.

My mother has flair and a merry nature, traits she infused in her cooking. A woman with a quick and light touch in the kitchen who always aimed to impress, Mum liked to experiment, learn, adapt and share. In the same way my Libyan-Palestinian father had travelled throughout the Arab world during the seminal sixties and seventies era of pan-Arab ideology, discussing and sharing ideas and thoughts with others from the Levant and north Africa, so too did my mother on matters related to society and culture, particularly food.

In truth, Mum started out as a terrible cook when, a few months shy of 19, she married my father and moved to London where he was stationed as the Libyan ambassador. Embassy life came with staff, meaning she didn’t have to cook for the first two years of their marriage. But when my father abruptly resigned his post and became a political dissident, they forwent all the trappings to which they had been accustomed and my mother had to quickly learn how to become the mistress of the kitchen.

Night after night she would attempt to recreate the sumptuous dishes that her mother had assiduously concocted in the kitchen that flanked the courtyard Damascene house in which she grew up.

After too many of my mother’s culinary experiments left my father hungrier than before they had sat down for dinner, he suggested that she make the one dish she had thus far made palatable. Lahme bil sa7n, or kofta, called for a recipe that in its simplicity made for an easy success — after all, it is just seasoned minced lamb rolled out in a pan and put in the oven. Never one to shirk from a challenge, my mother continued haunting the family kitchen, learning and experimenting, until her food flourished.

Driven by love, my mother made sure her expanding culinary repertoire also included Libyan and Palestinian cuisine.

Couscous, a north African dish popularized by Morocco but familiar to the Libyan kitchen, was a staple at our table, particularly when guests were present. A fixture in Palestinian cuisine, couscous was referred to by my father, who was born and raised in Haifa, as maftool — tiny rounds of wheat fluffed and reddened by tomato sauce dressed in chunks of cooked carrot, potato, zucchini and softly stewed lamb, all further garnished by chickpeas and sliced sweated onions.

Many a party was hosted at our home with couscous at the centerpiece. It provided an innocuous doorway to Libya at a time when the country was infamously out of bounds. Colonel Qaddafi and Back to the Future made Libyans out to be cartoonishly terrifying, but those light little carbs of delight humbly humanized a vilified people.

Since my father was a member of the Libyan opposition cadre in exile in the UK, visiting the country of my paternal heritage was too dangerous to contemplate and I only went to Libya for the first time in my life when I was at university. Therefore, growing up in London, my apolitical ties to Libya were primarily nourished by its culinary offerings and my mother’s efforts to bring her children’s ominous and distant fatherland close to us over dinner.

Mubakbaka, a food coma-inducing pasta dish whose name comes from the “bak bak” sound made by the bubbling sauce while cooked, was another Libyan delight my mother artfully mastered. She was first introduced to it when one of my father’s nephews visited them while they still lived at the embassy. One late evening, after the cook had retired for the day, their guest felt hungry and headed down to the kitchen to make something for himself. My mother followed, intrigued by what a Libyan man might rustle up. He finely chopped some onions and garlic and fried them in oil before adding large chunks of lamb on the bone and seasoning with cinnamon, turmeric, all spice, chili pepper and salt. After sautéing, he added heaps of tomato paste and water and let it come to the boil then simmer and stew. Once the lamb and sauce were cooked, he added the pasta to the pot to cook in their combined juices.

“See this sauce, Rehab? You master this, you master all the Libyan dishes — it’s the basis of them all,” he told her.

Mubakabaka featured more prominently on our dinner table during England’s cold winter months. The piping hot mounds of penne soaked in a thick spicy sauce topped with melted chunks of lamb were like an all-body hot water bottle and turned us all into famished carnivores. So loved by Libyans is the carb-heavy dish that it even found its way into my parent’s revolutionary activities in exile. Before I was born, the basement of our home was the de facto headquarters of the Libyan Democratic Assembly, the opposition movement founded by my father. During one of the many secret meetings held there, my mother was asked by a group of would-be Libyan revolutionaries if she wouldn’t mind making them some mubakabaka for lunch instead of the sandwiches she had been preparing for them.

Another regular winter warmer was muhamasa, a stew of round pasta balls in tomato sauce (the very same) with a variety of beans and pulses. Served in a cavernous round bowl, it is an immensely hearty meal that invites the cold and hungry to tuck in.

Our family dinners weren’t all large vats of pasta, mind you. With an almost religious-like consistency, every mealtime spread included three main pillars: salad, soup and a small plate of whole green chili peppers. The spicy nightshades were constant companions of my father’s chomping. In between morsels of okra stew — bamye — or green beans and lamb — loobia — he’d bite into one of his mouth-burning green friends, before proceeding to regale us with stories of his childhood in Palestine, adolescence as a refugee in Syria, teaching years in Qatar and monarchy-toppling revolutionary activities in Libya.

Sitting at the head of the table, his tales were the garnish to our nightly family meals and no story, however many times he repeated it, ever lost its intrigue or moral philosophy. Though my father’s revolutionary activities had quietened down by the time I was a young child, he never fully retired his political activism. Our dinner table was therefore also an education in the socio-political statuses of the Middle East in which we were all invited to participate, analyze and argue over. Between the food and the conversation, our dinner table became a living shrine to a region we yearned for.

My deepest longing was for Syria, the country we visited yearly during the summer months. Every trip was always inaugurated with a plate of koosa mahshy — courgettes stuffed with seasoned rice and spiced lamb pieces. It didn’t matter the time of the day we landed in Damascus, our family’s favorite Syrian dish would be waiting for us like a hearty salam. Prepared by my exceptionally talented aunt, this dish was the firing gun for a season spent feasting on Syrian delights that included, warak enab, kibbeh bil laban and fasoolia.

During the cold, dark and often lonely school term days in London, my memories of the sunshine, relatives, music and merriment of summer were always bittersweet reminders of the painful distance of diaspora. Thankfully, Mum’s dinners in the UK kept Syria just close enough to us to endure its gaping absence. However, for the longest time, I didn’t realize that her variations on dishes I ate and loved were a loving homage to another part of our Arab heritage that had an even more painful and enduring absence: Palestine.

For example, Mum would prepare lentil soup the Palestinian way, where the beans, rice and vegetables are cooked and whizzed into a smooth chowder instead of Syrian style, where the rice grains are kept whole and mincemeat and finely chopped parsley are added.

My mother also made mlookheye, a celebrated dish claimed in multiple countries of the region, the Palestinian way, smooth and soupy, instead of keeping the Jew’s mallow leaves whole and frying them, the way the Syrians typically do it.

As for maqloobeh, my personal absolute favorite Arab dish, my mother’s variation on that was yet another testament of the loving adoration she had for my father. A rice and lamb plate typically made with fried aubergines, my father’s extreme distaste for the bulbous, black-skinned vegetable meant it was replaced with fried cauliflower instead, even though my mother had always been averse to cauliflower herself.

Children from immigrant backgrounds can sometimes feel self-conscious about the “different” food in their cuisine to that of their native countrymen. Thanks to a primarily international education, difference wasn’t such a big problem but being Arab was, particularly in the post-9/11 overnight cultural assassination that happened to those of browner complexions with foreign names. The soft power of food became the only acceptable show of force for people like us. Food was also a way for me to feed a different narrative of the region plagued by the unfair reputation that its only offerings are violence and refugees.

Inviting friends over for dinner was a regular and encouraged practice. Gastronomical generosity is, after all, a renowned regional trait and it’s also much easier to humanize a region when you’ve handsomely licked its delicate tastes from your lips. My parents encouraged us to invite guests home for dinner, such that an extra seat was practically always set at our table. It was an opportunity to “set the record straight” on what Arabs were really like. While scooping mounds of rice and beans and okra and lamb on our guests’ plates, we’d talk of the magnificent Roman ruins across the Levant, or about the liberal culture of mountain-to-sea-in-a-day Lebanon or of the tolerant society in Syria. “And did you know that Arabs invented algebra?” and our non-Arab guests would nod, chew, purr and eventually roll away, satiated and happy with a new concept of what it meant to be an Arab.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)