And yet, I know all about Arab happiness in Paris. It was my father's face that lit up with a magnificent smile every time the word Paris was uttered.

The title sounds like a paradox, almost violent to write and read.

It’s rare these days, when one thinks of “Arabs” and Paris, to associate it with feelings of happiness and bliss. Parisians in general are not renowned for their joie de vivre. Arab Parisians in particular have a few additional reasons to lament the miseries of life in the City of Light.

In our literature, the first feeling of Arabs discovering Parisian life is that of exile, the “ghorba,” a feeling of otherness, strangeness, cruel coldness, disarming frigidity, or inadequacy provoking a certain moral, even physical distress.

In today’s media, depending on whether you’re on the left or the right, the words that come to mind revolve around delinquency, discrimination, educational failure, suburban Salafism, street prayers, creeping kebabs, inelegant wesh-wesh (how are you greetings), S files on the loose, even the war of civilizations. The times like to explore the collapsological depths of a secular, subtle and delicate Judeo-Christianity that is eroding, besieged by hordes from elsewhere shouting Allahu Akbar… Little joy or happiness in this cursed association…

At most, to complete this apocalyptic topography, there are unappetizing images of young millionaires from the Gulf blowing their oil and gas fortunes at decadent parties, rich in drugs, call girls, scattered dollars and assumed vulgarity. Arabism and the Paris of today are a decidedly problematic couple.

And yet, I know all about Arab happiness in Paris. It was my father’s face that lit up with a magnificent smile every time the word Paris was uttered. The idea of Paris, a memory of Paris, a plan to go there, any evocation of Paris made Si Mohammed El Kabbaj joyful, happy and perky, whatever the circumstances of his life. They gave him, despite his respectable age, the excitement of a young child who had just been promised a wonderful toy.

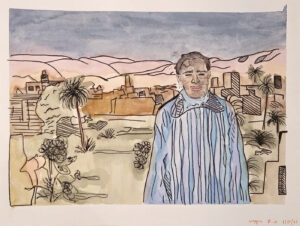

My father was a true Arab, in the cultural sense of the word. He grew up in a family that cultivated its Arab and Islamic identities. He went to Koranic school in Oran in the ‘30s. He ran through the alleys of Fez, not far from the Qaraouiyine University where his sister became a doctor of theology. As a child, it was common for ulama (religious scholars) to enter the family home to discuss some theological or political topic. When little Si Mohammed was about ten years old at his native school in Fez, he was noticed and chosen to join the Imperial College along with Prince Moulay Abdallah.

In this venerable institution, he acquired an Arab-Muslim, Moroccan culture, literally fit for kings. He also had his first, and beautiful, encounter with the most classical of Western cultures. Renowned teachers taught him French, Latin, literature and poetry, mathematics and science. During certain classes, Sultan Mohammed V, known for his modesty, would come and sit next to him, to acquire some knowledge from this generation of hopefuls for the country. This fairytale episode came to an abrupt end when the royal family was exiled by the French authorities in 1953.

When he managed — and it wasn’t easy — to convince his pious, deeply patriotic and pan-Arab father that Paris would be his destination for higher education, I can’t imagine how happy he must have been, crossing the Mediterranean to Marseille and then Paris. His encounter with Paris was a marvel, a firework display that would change his life forever.

In his first months in Paris, he often walked in the Luxembourg Gardens, between his boarding school at the Lycée Saint-Louis and his “Maths sup” (higher mathematics) classes at the Lycée Montaigne. Perhaps it was in these alleys that he developed a lifelong love of gardening. Later, when we walked through the Luxembourg Gardens during my own move to the Lycée Louis le Grand, or when we took my son for a walk in his stroller many years later, he never failed to quote these lines, engraved in his memory, from Anatole France: “I’ll tell you what I see when I cross the Luxembourg in the first days of October, when it’s a little sad and more beautiful than ever; for it’s the time when the leaves fall one by one on the white shoulders of the statues. What I see in this garden then is a little man, his hands in his pockets and his satchel on his back, hopping off to school like a sparrow. My thoughts alone see him; for this little fellow is a shadow; it’s the shadow of the me I was twenty-five years ago.”

While his fellow preparatory students were plunging into the esoteric depths of differential equations, demonstrations and theorems, my father took a liking to a beautiful soul at his lycée, who provided him with an endless stream of invitations and discounts to cinema screenings, plays, ballets, operas, exhibitions — magical access to a cultural life he’d never known existed. He threw himself into it as if nothing else mattered. Corneille, Molière, Kurosawa, Antonio Vivaldi, Samuel Beckett, Alexandre Pouchkine, Niki de Saint Phalle, Ariane Mnouchkine, Jean-Pierre Melville — these were the names of the friends who populated those nights.

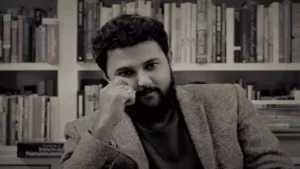

With Maryse, a Corsican friend with a strong temperament, “Lazard,” his blue-eyed cousin with whom he shared the same first and last name and “Arthur,” another cousin with a British sense of humor, they painted the town red. His nickname was “the bearded one,” He called himself a Patagonian to anyone who asked. They were free and anonymous. Paris was their playground. He went to the Beaux-Arts, took courses in architecture and plastic arts. He produced china inks, oil canvases exploring the obscure meanders of the abstract, and avant-garde photos developed in his darkroom. He frequented artists such as Gharbaoui, a great name in contemporary Moroccan painting, who died on a park bench in Champ-de-Mars before achieving fame.

For my father, Paris was one of the great loves of his life. 15 years after leaving it, when he was afraid of dying in his fifties, battling particularly violent and unexplained vertigo episodes, to my mother who asked him, “What do you want to do?” he answered without hesitation: “Go to Paris.”

His semiannual visits to Paris were the essential ingredients for a wonderful year. Walks in Luxembourg, plays, hot teas in cafés in winter, ice creams on the quays in summer, book-buying in independent bookshops, visits to exhibitions — a salutary and joyful intellectual breath before plunging back into the daily grind of life in Casablanca.

When he visited me in Montpellier, nine months before his death, I remember seeing him at the stop watching a TGV on our platform, ready to leave for Paris. We had just arrived from Marseille to spend some time in Occitanie. He stared at the TGV for a long time. I teased him. “Do you want to jump on this train and go to Paris, or are you trying to breathe in the Parisian air it’s brought back in its carriages?” That day, contrary to his habit, he didn’t smile or reply with a snide remark. He looked at the train with gravity and melancholy. He didn’t yet know that a cancer was silently eating away at him. But he probably suspected that the Paris of his life was inexorably slipping away.

For the generation of North Africans who preceded us, Paris was a beacon, illuminating their lives with teachers and authors who opened up a whole universe to them that their parents didn’t have access to. It was their rational and intellectual Mecca. It was a space of freedom, where they could have fun without worrying about the rigid rules of their environment, a café, a terrace, and their spirits could dance and their dreams spread.

No, Arab and Muslim culture and civilization are not incompatible with French culture and its Parisian temple. When the material and environmental conditions are met with a minimum of decency, these cultures mix with pleasure, respect and harmony.

Rest in peace my dear baba, Si Mohammed, le Parisien.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

Magnifique texte. Très émouvant. Merci