Imperial air routes from European capitals to their Asian colonies once connected Gaza and Singapore. Under occupation, Palestinians have repeatedly been denied their own civil aviation; this symbol of freedom, modernity and statehood is deeply connected to their quest for sovereignty.

The first people to fly from Gaza to Singapore were four Australian aviators in 1919. Ross Smith was a decorated Australian Flying Corps pilot; T. E. Lawrence, who flew in Smith’s plane on several occasions, declared that Smith “climbed like a cat up the sky.” (T.E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Apostrophe Books, 1935, Ch, CXIV). Ross’ brother Keith Smith was a British Royal Air Force veteran, and accompanying them were the mechanics James Bennett and Wally Shiers. The quartet was pursuing a prize of 10,000 Australian pounds offered by the Australian government to the first team to fly from England to Australia within 30 days. On November 12 the four men set out from Hounslow Heath in a Vickers Vimy, and on November 19 they departed Cairo and flew toward Palestine. Ross Smith recalled their approach: “El Arish, Rafah, Gaza — all came into being; then out over the brim of the world of sand. Gaza from the air is as pitiful a sight as it is from the ground. In its loneliness and ruin, an atmosphere of great sadness has descended upon it. On the site of a once-prosperous town stands war’s memorial — a necropolis of shattered buildings.” (R. Smith, 14000 Miles Through the Air, Macmillan, 1922, p. 55). Eight thousand kilometers later, on December 4, the Vimy touched down to great fanfare in Singapore. The British island colony did not yet have its own airport, and that day’s improvized airstrip was the Singapore horse racing course that doubled as a rifle range and golf course. Landing on the short strip required some unorthodox creativity; in Smith’s words, “just before we touched the ground Bennett clambered out of the cockpit and slid along the top of the fuselage down to the tail-plane. His weight dropped the tail down quickly, with the result that the machine pulled up in about `100 yards after touching the ground.”

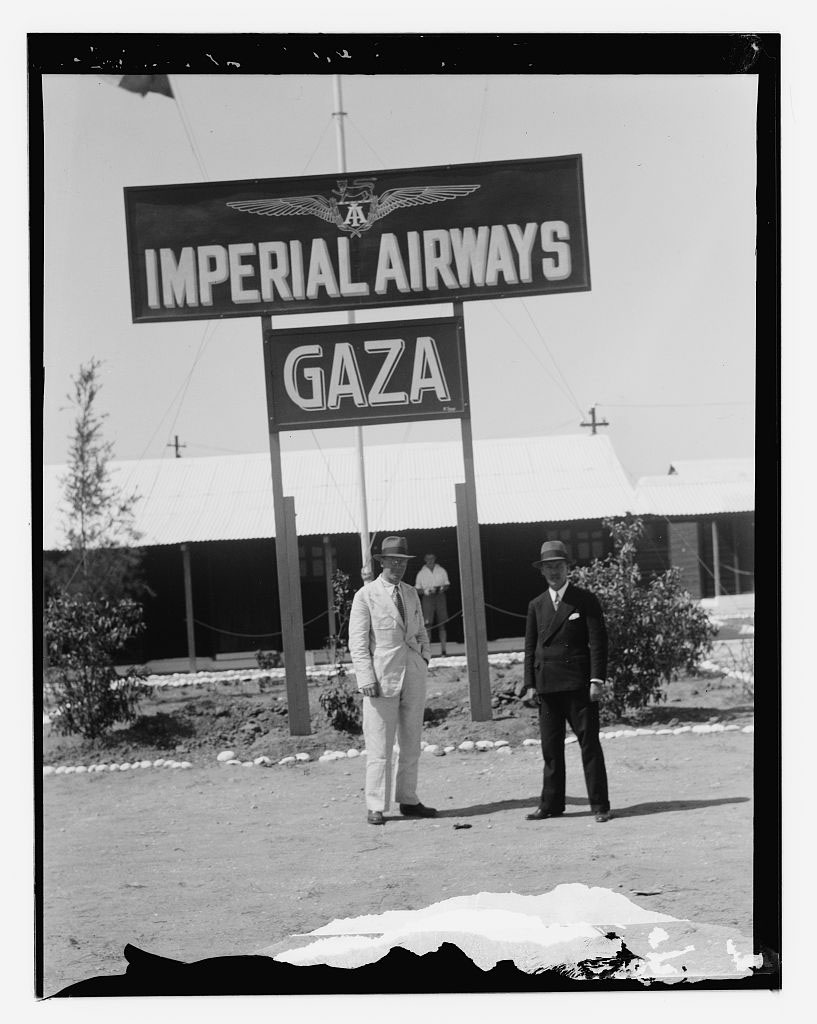

Of course, neither Gaza or Singapore, my home country, were the true highlights of this historic England-Australia flight. Still, I love this story because it captures a very different time when civil aviation promised adventure and modernity, and when Palestine, especially Gaza, had not yet been brutally decoupled from the world. During the golden age of aviation, both Gaza and Singapore featured on the pioneering route maps of the British and Dutch flag carriers Imperial Airways and KLM, stalwart stops on eastern connections unfurling from London and Amsterdam to connect the sprawling conurbations of Cairo, Baghdad, Karachi, Delhi, Calcutta, Bangkok and Batavia. It was a time when Palestine and Singapore had not yet embarked upon the diverging paths that would give rise to the saying that Palestine, or Gaza, could have been the Singapore of the Middle East. This proposition, likely first articulated in 1988 in a New York Times letter to the editor, mainly services a neoliberal vantage point that faults Gaza’s leaders for deliberately eschewing a path of prosperity and stability, blithely ignoring the issue of Palestinian self-determination and a host of political factors. Nevertheless, this flawed Gaza-Singapore analogy stirred up unexpected emotions of empathy and curiosity in me, as if Gaza, that walled-off yet spectacularly mediatized source of suffering, was shedding its light afar upon my relatively fortunate country and myself.

I traveled to Gaza and the West Bank thrice to research and produce documentaries on refugee issues,. Out of all the occupation’s material manifestations I found Israel’s elaborate obstacles to Palestinian mobility most absurd and cruel. To get on an airplane, Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem mostly travel to Amman to fly from Queen Alia International Airport; the few that fly through Israel’s Ben Gurion International Airport often endure humiliating security checks and invasive interrogations. After Hamas gained control of Gaza in 2006, Palestinians from Gaza would travel to Egypt and through the Sinai desert to take a plane from Cairo. The Rafah crossing to Egypt opened irregularly depending on political and security developments, and people often waited weeks or months for the necessary permits to exit for medical treatment, education, employment and business opportunities. Many Palestinians outside Gaza were also stuck waiting for the crossing to reopen so they could go home.

During my first trip to Gaza with the artist Ai Weiwei who was directing Human Flow, his documentary about the global refugee crisis, the Rafah crossing happened to open, and our local fixers rushed us there to film the assembling crowds. Leaving Gaza was a multi-stage process involving hours of waiting in consecutive locations: first in a repurposed basketball court, then in the checkpoint’s waiting premises, then in the bus terminal where buses departed to Egypt. After what seemed like hours, one fully packed bus departed through the compound gates, only to return shortly with the same busload of faces, now fallen and angry. “What happened?” I asked our fixer. He shrugged, resignedly. “Security.’” It had been a long day for our film crew, but it had taken months or even years for some Palestinians to get on that bus. Then, in one surreal moment, a young man leaned out of the bus window and excitedly shouted, “Hey — Ai Weiwei!” As the dejected passengers disembarked, the young man came over to chat with us, and it transpired that he was a Palestinian now living in New York and trying to return home! It was an unexpectedly poignant moment, this motley bunch of current and former New Yorkers finding each other at the Rafah crossing.

Ground to Air

In fact, just over 100 years ago, Palestine already hosted purpose-built airstrips whereas Singapore had none. The military aerodromes throughout Palestine were first built by the Ottomans and taken over by Britain’s Royal Air Force as the First World War ended. The Allied powers carved up the Ottoman Empire’s territories, and the League of Nations would grant Britain the Mandate for Palestine. Eight thousand kilometers to the east, another strategically located imperial outpost celebrated its centenary as a British crown colony. Since 1819, Singapore, an island at the southernmost tip of the Malay Peninsula, had flourished as a port due to its prime location in the Malacca Straits, through which all marine traffic traveling from the South China Sea had to traverse to reach the Indian Ocean. In the following decade Britain, pressured by the United States’ waxing maritime power and Japanese expansionism in the Far East, decided to construct its main Pacific naval base in Singapore, which included Seletar Airfield as the RAF’s first regional base.

Although these early airstrips began for military purposes, the popular fascination with civil aviation in America and Europe spread eastward like wildfire. The first demonstration flight in Singapore was performed in 1911 by the Belgian aviator Joseph Christaens, whose Bristol Boxkite biplane had been specially shipped in for the occasion. Two years later, the French aviator Jules Védrines became the first pilot to land in Palestine in his Blériot monoplane during a historic 5,400 kilometer race from Paris to Cairo. And then, in 1919, the historic England-Australia flight by the Smiths, drawing a definitive line in the air between eight countries, and between Gaza and Singapore. In May 1933 the Dutch flag carrier KLM added Singapore to its 9,000-kilometer Amsterdam-Batavia flight route, which also included Gaza as a stopover. The journey took nine days in Fokker XII and XVIII planes that each seated four passengers and four crew. In December that same year, Britain’s Imperial Airways inaugurated its long-haul flying boat service from London to Singapore, which traversed 21 stops including Paris, Athens, Alexandria, Baghdad, Gaza, Karachi, Delhi, Calcutta and Bangkok. Clocking in at ten days, the trip was significantly shorter than the 19-day ocean journey from London to Singapore. The flying boats could hold 17 passengers who were treated to a full-service menu, wine pairings and cigarettes.

The promising advent of these early air connections between Gaza and Singapore was soon aborted. In the next decades, their trajectories sharply diverged with the two nations’ political fortunes. Singapore was occupied by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945, joined the Federation of Malaysia in 1963 and left two years later become an independent state. Singapore’s Changi International Airport and its flag carrier Singapore Airlines are centerpieces of the city-state’s economic success story. As rapid advances in aviation technologies enabled the production of bigger and faster airplanes that required longer runways, Seletar Airport would soon be replaced by Kallang Airport in 1937, Paya Lebar Airport in 1955, and then Changi International Airport in 1981. In 1937 Wearne’s Air Service began the first domestic air service connecting Singapore to cities on the Malaysian peninsula. Singapore Airlines emerged from the corporate restructuring of Malaysian-Singapore Airlines in 1972 and went on to become one of Singapore’s most iconic brands with a 13 billion USD market capitalization.

Today, Changi Airport is an apt synecdoche for the city-state: a model of political life built upon concentrated and ceaseless flows of connectivity, transaction, consumption and surveillance. Every 80 seconds, a plane alights or departs; every flight is international since the island is too small for domestic flights. The silver lining of Singapore’s tiny geographical footprint is that many of its citizens are compelled to travel and learn about other cultures and systems; the young nation is an exquisitely managed model of the free market underpinned by selective state control, finely calibrated to exploit geopolitical and macroeconomic risks rippling from other ruptures of the world.

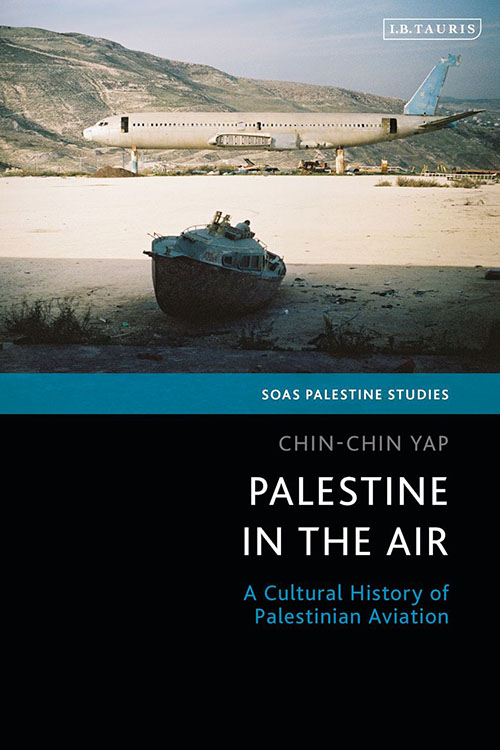

If we trace these ripples back through time, we see that even though Imperial Airways and KLM discontinued their empire routes decades ago, the neo-colonial tentacles of domination and extraction are still powerfully alive in contemporary guise. Gaza and Singapore, no longer visibly connected on aviation maps, have become waystations of another type—two different manifestations of late capitalism, reflecting dual outcomes of internationalized capital, accelerating inequality and mediatized hyperrealities. Mandatory Palestine’s civil aviation ended with the establishment of the State of Israel and the Nakba of 1948 in which 750,000 Palestinians were killed or forcibly displaced. For the next four decades, Palestinians were violently scattered in exile and in refugee camps, their political factions operating from Jordan, Lebanon and Tunisia. In 1993 and 1995 the Oslo Accords between Israel and the PLO created a blueprint for limited Palestinian autonomy in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, which included provisions for a Palestinian airport and airline.

A Break in the Clouds

“You had a Palestinian passport … you feel you are a human. You fly from your own land, on your own airline.” Najib Abu Jobain, an Associated Press producer originally from Gaza, spoke for many Gazans who ecstatically welcomed the Gaza International Airport and Palestinian Airlines. The airport and airline were the most prominent symbols of Palestinian autonomy, promising to literally connect Palestinians with the world. Palestinian Airlines undertook its first flight in 1997 with just three planes in its fleet; the Gaza International Airport was inaugurated by Yasir Arafat and President Bill Clinton in 1998. This new epoch of Palestinian aviation only lasted a couple of years. When the second intifada broke out in 2000, Israel destroyed the Gaza airport and its runway; Palestinian Airlines was forced to relocate across the border to Egypt, where its business faltered and never recovered. Today, many children in Gaza have never seen a civilian flight crossing their skies. They are, however, intimately familiar with Israeli drones and warplanes enforcing the occupation, which they can identify simply based on sound.

That day at the Rafah crossing, I thought that except for an accident of birth, I could have been one of those crestfallen passengers on the returned bus. We had just interviewed Mona Khurraz, a young university student on the Gaza beach, who said wistfully, “My dream is to travel the world … I want to see the second world outside and how people are living, to see places other than Gaza. We love Gaza. But what are people like outside?” (W. Ai, Human Flow: Stories from the Global Refugee Crisis, Princeton University Press, 2020, p. 273) The bus was likely packed with people like her trying to get a glimpse of that “second world” — “outside.”

As part of the long-running and pervasive dehumanization of Palestinians, we have come to regard them as a people who aren’t entitled to an airport or airline, who should jump through convoluted bureaucratic and logistical hoops just to board a plane, who may be subjected without reprieve to mass executions by airstrikes and quadcopters live 24/7 on social media, like some gruesome reality show. In our cultural imagination of the last century, Palestinians are largely absent from the grand project of air connectivity that transformed our world with new exploits and explorations. We barely think of celebrated Palestinians in aviation, with the exception of a few such as Loay Elbasyouni, the NASA engineer who helped design the Mars Rover, Suleiman Baraka the NASA astrophysicist, or, somewhat ironically, Leila Khaled, the first female airplane hijacker whom The Guardian christened “the international pin-up of armed struggle.” More ominously, the occupied territories’ airspace has become Israel’s testing grounds for aerial technologies, which are then sold to foreign governments and militias as “battle-tested” weapons to be deployed on refugees and politically undesirable populations. How did we normalize human flight — our beloved, even primordial metaphor for adventure and connection — as a medium for so many ghoulish varieties of injustice and oppression?

But all this happened in the last 80 years, a blink of the eye in historical time. Some of those bus passengers could have proudly flown on Palestinian Airlines from the Gaza airport, or their parents from an airport in Mandatory Palestine. A pilot facing massing clouds knows that they will give way to blue sky. One fine day, when peace has settled upon us, there’ll be new air connections from Gaza, or Qalandia, not only to Singapore but to all the world’s capitals. Like Ross Smith chasing his prize, we’ll see Gaza rising, and fasten our seatbelts for the descent into Palestine.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)