During this time of genocide and attempted erasure of Palestinians, we have a large body of poems and other writings composed by Palestinians, both inside and outside of Gaza. In his latest collection, Fady Joudah takes on the inadequacy and necessity of language to convey the pain and hope of Palestinians right now as he pushes against a challenge Palestinian poetry faces, perhaps especially poetry written in English, where poets, as much as they resist doing so, are expected to explain the Palestinian condition.

[…] by Fady Joudah

Milkweed Editions, 2024

ISBN 9781639551286

Eman Quotah

What future will we look back from, onto the current moment? An unprecedented catastrophe, when Israel’s military has killed and buried tens of thousands of Palestinians alive in a matter of months. This moment (meaning “period in time”) when every moment (meaning “fraction of an hour”), the Israeli state kills even more Palestinians in Gaza, by bullet, bomb, or starvation. This moment when the words we wrote one week after Hamas’ invasion and killing of 1,200 Israeli Jews and others, one week after the beginning of Israel’s bombardment and ground invasion that has, as of now, killed more than 30,000 Palestinians, including so, so many children — when what we wrote then about the scope of the horror Gazans faced seems no different than the words we could write today. And yet every day the horror intensifies. Words are never adequate and often racist; grammar fails; adjectives seep in bias. And time keeps accumulating.

![[...] poems by Fady Joudah cover](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/poems-by-Fady-Joudah.jpg)

Palestinian American poet, translator, and physician Fady Joudah’s […], his sixth collection of poetry, takes on the inadequacy and necessity of language to convey the pain and hope of Palestinians right now.

Joudah has lost many family members in Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. Written mostly from October to December 2023, his new volume’s non-title repeats as the non-title of more than half its poems. In resisting titling and the way titles make and direct meaning — not just by leaving his work untitled but by drawing attention to his erasure of titles — Joudah makes a bold craft choice. On the “PalCast – One World, One Struggle” podcast on March 5, the poet explained, “I couldn’t imagine words as the title” of the collection.

Instead, he wanted to indicate silence: the silencing of Palestinians in what he refers to as “English” — by which he says he means the “language of hegemony,” whether English, French, or German. To acknowledge the world’s tendency to yank away from Palestinians their ability to be silent, a silence they sometimes need, whether out of grief or in search of healing or because words cannot express the magnitude of their losses and grievances.

And also, the silencing that is death.

“It is a book that asks people to really consider what kind of listening have they not been offering to the Palestinians,” Joudah said on the podcast. “What kind of listening they think they have been offering to the Palestinians but have not, especially in English.”

In other words, a book that tells us to shut up and listen.

The recent kerfuffle at Guernica magazine underscores Joudah’s point. In early March, the magazine retracted “From the Edges of a Broken World,” an essay by British-Israeli writer and translator Joanna Chen, following the resignation of dozens of volunteer editors and slush readers over the essay’s publication and months-long internal disagreement about the magazine’s stance on Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions. The retraction has been criticized widely. But predictably, none of the half dozen or so news or opinion articles about the controversy traces the series of events back to the Palestinian writers whose criticism of the essay on X triggered the resignations. And none truly engages with their critique of the article as colonialist and unwilling to truthfully grapple with Israel’s apartheid realities. Those writers included Joudah, who pulled from a forthcoming publication at Guernica a Q&A that has now been published elsewhere.

Much can be made of the symbol […], but how does it [re]direct our reading of the poems? It is a convention in poetry to refer to an untitled poem by using the first line or a portion of it in brackets or parentheses. So, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 is [Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day], and the first sonnet of Diane Suess’s Frank: Sonnets is [I drove all the way to Cape Disappointment].

With that logic, Joudah’s poem […] that begins, “Daily you wake up to the killing of your people, their tongue accented/in your mother’s milk,” is denied a bracketed title, and is therefore also, perhaps, missing a first line. The line isn’t there because we weren’t listening. Because the narrator has not wished us to hear it. Because the narrator began with a line of silence. Because the line was erased or removed, by the narrator or a censor. Because […].

Similarly, the poem […] that begins:

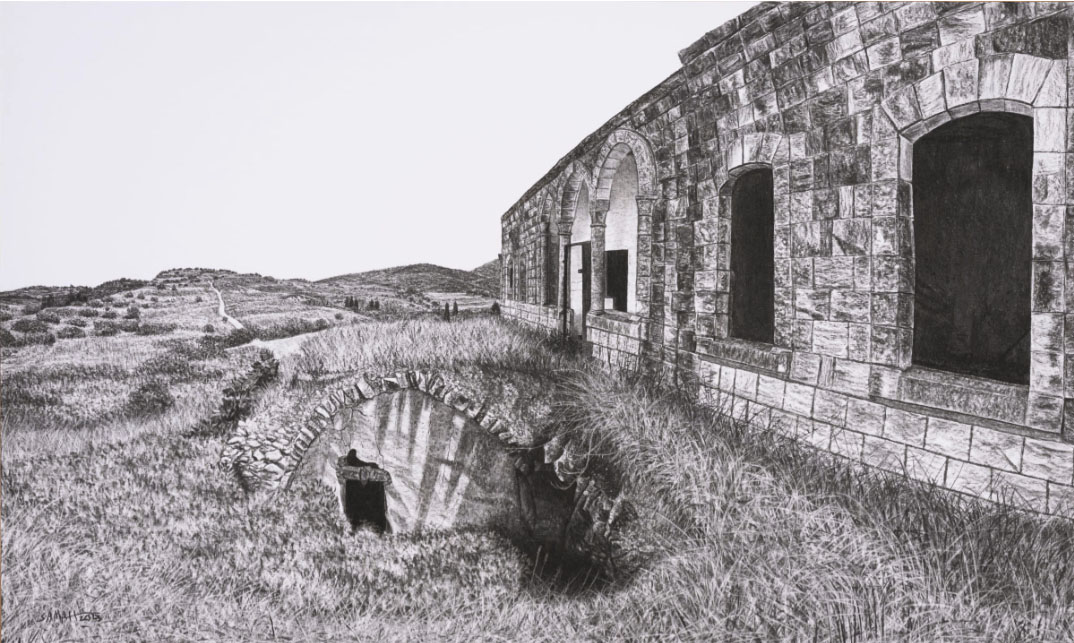

You have entered the tunnel.

There is a light in the endless tunnel.

Every word you think of

has already been written

by you or others who skim

the spume of their seas.

They love to travel.

They love you more when you’re dead.

You’re more alive to them dead.

How do we read and understand these lines when we perceive them to have been preceded by a blank space? A line we cannot make meaning of because of its absence? Does the missing line suggest the tens of thousands of missing Palestinians in Gaza, buried under rubble or buried anonymously? Or the thousands of Palestinians Israel has detained, the thousands missing from their homes and families and communities? Does it suggest endless displacement?

Does the silence force you to listen?

Now, read the first lines of this next one, and imagine a long pause, a deep breath taken before speaking, or a silence lasting a moment or more — a moment of silence, if you will — at the beginning:

[…]

They did not mean to kill the children.

They meant to.

Too many kids got in the way

of precisely imprecise

one-ton bombs

dropped a thousand and one times

over the children’s nights.

Joudah is not alone among Anglophone (or, more accurately, bilingual) Palestinian poets in rendering absences visible. For example, Palestinian American poet, novelist, and psychotherapist Hala Alyan’s Revision, published in November 2023, makes itself illegible at times:

I had a grandmother once.

She had a memory once.

It spoiled like milk.

On the phone, she’d me ask about my son, if he was fussy,

if he was eating solids yet.

She’d ask if he was living up to his name.

I said yes. I always said yes. I asked for his name and it was [ ].

I dreamt of her saying:

[ ]

[ ]

[ ].

And several lines later, Alyan writes:

If you say Gaza you must say [ ].

If you say [ ] you must say [ ].

I’ve heard Alyan read this poem, and when she reads the bracketed blanks, she says, “Redacted.” It’s chilling. It evokes censoring by others, self-censorship, and false listening, as when politicians say they are concerned about civilian deaths but we can imagine them plugging their ears with their fingers and saying, “Lalalalala” (which in Arabic we hear as “Nonononono”). When you or I read or listen to Alyan’s or Joudah’s poems, we should think of what Palestinian American writer and performance artist Fargo Nissim Tbakhi says about catharsis in his essay “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide”:

Nobody should get out of our work feeling purged, clean. Nobody should live happily during the war. Our readers can feel that way when liberation is the precondition for our work, and not the dream. When it is the place we stand, and not the place we shake ourselves towards.

In his collection, Joudah pushes against a challenge Palestinian poetry faces, perhaps especially poetry written in English, where poets, as much as they resist doing so, are expected to explain the Palestinian condition. The problem, of course, is not the poetry itself or the Palestinian-ness of the poet, but rather the ongoing, relentless occupation and Nakba. The feeling of being stuck in a time loop, so that a poem written in 2021 or 2014 or 2011 — or 1982 — about the state of occupation and apartheid, bombardment, and impending Palestinian death, reads like it could have been written today, and vice versa. Take Palestinian poet and professor Refaat Alareer’s now-famous “If I Must Die,” in which the narrator contemplates his own death and asks the reader to remember him: “If I must die/you must live/to tell my story.” Alareer posted the poem on X, formerly Twitter, a month before the Israeli military murdered him and members of his family in Gaza in a targeted strike on December 6, 2023; many people on social media who read the poem then thought it had been freshly written. In fact, Alareer wrote “If I Must Die” in 2011.

Alareer was not clairvoyant. He couldn’t see the future. He was simply living under the conditions of an endlessly repeating cycle of life-threatening terror.

Joudah pays homage to Alareer’s poem — which has, since Alareer’s death, been translated into some 40 languages — and to the poet himself in a poem [un]titled […] that begins with the lines, “Suddenly I/’in a blaze’ died.” It is given pride of place on the back cover of […], where normally blurbs and a book description would go. Unlike Alareer’s lyrical, hopeful verse, with its image of a white kite in the sky that a child believes is an angel looking down, Joudah’s poem is fitful and frantic, unwilling to pass to the reader the cathartic role of storyteller and torchbearer. And yet it ends powerfully with “I” (repeating its first line), as though the martyr is reborn, repeatedly, despite the occupier’s every attempt to snuff him out. Read together, Alareer and Joudah’s poems deliver and defy sentimentality; they soar and crash into the ground; they accept the so-called inevitable and resist it; they embrace beauty and lyricism and reject it.

The power of “I” reveals itself even more when one turns to the book’s final poem, “Sunbird.” The narrator moves from I to we, and back again, beginning with the lines, “I flit/from gleaming river/to glistening sea.//From all that we/to all that me.” Soaring with the sunbird (also known as the Palestine sunbird, and a symbol of Palestinian freedom, resistance, and hope), the poem moves across all directions of the land, “Fresh east to salty west,/southern sweet//and northern free.” Finally, it swoops, “From womb/to breath,/and one with oneness//I be:/from the river/to the sea.”

In that spirit of oneness, Joudah’s collection is best read in conversation with other Palestinian poets writing in this moment. Alyan, as well as Zeina Azzam, whose “Write My Name” was written and published last fall in response to reports that Palestinian parents were writing their children’s names on their limbs to help identify them if parent or child died. Mosab Abu Toha’s every tweet and Instagram post has become something like poetry of resistance and witness over the past five months. Haya Abu Nasser, currently in Gaza. Rasha Abdulhadi, who turns even her bio into a document of protest. And many others. As well as the work of other Arab writers, like Omar Sakr’s “… in the Genocide” series of poems.

Most importantly, Joudah’s poems and the work of these other poets cannot simply be words we read. To read the work of Palestinians now and not also speak out or take action to end the genocide, to return all Israeli and Palestinian hostages home, and help strive for freedom and liberation for all is a betrayal of epic proportions. We can’t allow ourselves to feel catharsis. We must really listen so the future we look back from is the future we want and need.