The Fugitive of Gezi Park, a novel by Deniz Goran

Ortac Press 2023

ISBN 9781838388744

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

I find it difficult to pin down what exactly characterizes the contemporary novel, thinking beyond genre, form, style and so on. In the absence of coherent themes or features, contemporary fiction embraces a paradoxical ambivalence between uncertainty and realism, often embedded in questions of cultural heritage, emphasizing the condition of a world without center. Often when confronted with hyperrealist characters and situations, depicting our everyday life today, we look back and find the real ungraspable, increasingly chaotic and disjointed.

Even speaking of a global voice becomes an oxymoron, when the world is no longer a globe as such, but a series of points, dispersions and displacements.

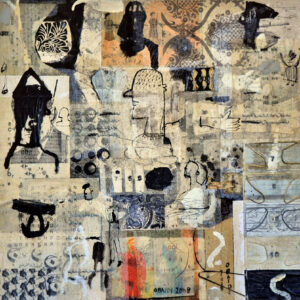

Deniz Goran’s novel The Fugitive of Gezi Park, belongs in this genre of difficult to define novels, set in present-day London, but articulating a sense of displacement between Turkey and Europe, a displacement that is not only geographical: The author writes in a foreign language that is no longer foreign, in an interminable sequence of memories, monologues, reflections and sparse dialogues that are constantly interrupted by even more reflections in a temporal disarray that is hard to piece together. It is perhaps this overcluttered narrative that gives the novel its true contemporaneity: The events are familiar, and the characters realistic enough to be believed, but the internal tempo is completely disordered. It’s a cinematic ensemble, spiraling in all directions.

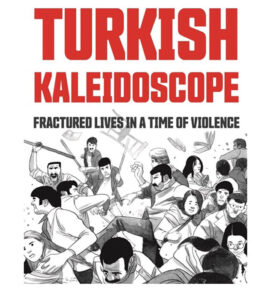

Ada is a young woman from Istanbul, who relocated to London for an art history degree, and finds herself suddenly caught up in the Gezi Park protests during a summer in Istanbul in 2013 (the novel is set in that year and its publication is meant to shed light on the emotional value that the movement still has for dissidents in Turkey a decade later). Her participation leads to her arrest and eventual escape from the country, and the struggle to reinvent herself elsewhere, without knowing whether she will be permitted to return.

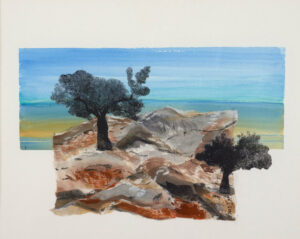

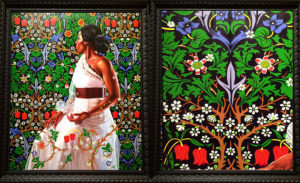

The author depicts a country from which her protagonist has become estranged, and looks back at from a place of alienation, for in Ada’s London there are no descriptions of the outdoors, nature or the underprivileged. The entire novel takes place in a placeless but defined setting — the art world. Whether it is an art fair (I’ve frankly never read a novel that takes places at an art fair; the effect is almost comic), or elegant party salons, ornate Ottoman buildings, and wealthy homes in Fitzrovia and Mayfair, the professional conversations about art dominate the narrative, and the events of Gezi Park, particularly traumatic ones in Ada’s case, begin to bubble up only slowly, forming a kind of historical subconscious that although recent in time, appears to the reader almost remote today, and remind us of the degree to which Turkey has fallen out of grace since then. A pregnant moment of possibility has become a vague memory, but one powerful enough to rapidly conjure up vivid flashbacks.

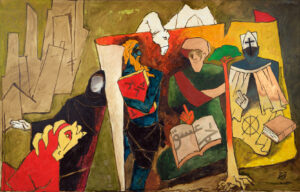

But the protagonist isn’t anything like the victims of state violence that we are accustomed to hear about: She is the daughter of a famous painter and exists in a world of scandalous privilege — material, social, cultural — so perplexing if only because of how little need there is in the novel to explain that Ada is not like the rest of the protesters at Gezi. And here comes into the play the powerful chaos of contemporary fiction: The events are so close in time, so amalgamated with the real facts, so believable, that it’s hard to discern whether the author is being confessional, or satirical, or perhaps drawing on her previous novel, The Turkish Diplomat’s Daughter (2007), a polemical but uproariously humorous novel about a woman’s search for sexual freedom.

As a work of fiction, The Fugitive of Gezi Park is actually an incredible portrayal of the very small and elitist club of Turkish contemporary art, with its family names, London residencies, political maneuvers and all too fragmentary recollections of their own past, and Ada’s introspections, particularly in regard to the troubled present of the country, are refreshingly sincere in their partiality, and reflect the still untold and unfinished story of Gezi Park. Lucian, on the other hand, the secondary character, is an eccentric upper-class Londoner and gallerist, whom Ada meets at an art fair while trying to sort her luck, but remains all too conventional in his extravagance, and only superficially interesting. His aristocratic boredom expresses more alienation than psychological complexity.

The Ghost of Gezi Park—Turkey Ten Years On

The Fugitive of Gezi Park isn’t anything like a linear narrative where events simply unfold. The arrow of time might always go forward, but the novel is a series of vaguely interrelated recollections in the first person, told by Ada and Lucian. There are, however, some exceptional flashbacks and detours, such as the beautiful descriptions of Ada’s father and his library, the semi-orientalist descriptions of Istanbul and Gezi Park from a distance, or the blurry distinction between social class and political orientation that permeates the political landscape of an intensely polarized country. At times, fiction and reality blend, not necessarily in the accuracy of events, but in the adopted postures of a demoted bourgeoisie struggling to come to terms with a changing reality.

The novel is as sexually charged as Goren’s previous work, and the rambunctious descriptions of sex, physicality, and the female body, are both liberating and liberated. It is indeed rare to see a Turkish author engage the body in such an unflinching, unrestrained and brutally honest manner. This tells us as much about the author’s constant search for freedom in her work, as it does about the level of repression that makes it impossible to publish a novel such as this in Turkish or in Turkey. Deniz Goran (a pseudonym for Selin Tamtekin, who happens to be an art writer as well), is not the first Turkish writer that has turned to English in order to express freely what many in the country feel, and this book feels like a raw exercise in processing this grief.

In the end, The Fugitive of Gezi Park is really a novel about toxic authoritarianism, and the ways in which it has shaped the lives and destinies of countless young persons in this country, sometimes through exile (as in the rather lucky case of Ada), but often also through imprisonment and disappearance. While being immersed in the glamorous London art world, one that moves so rapidly as not to leave one enough space to breathe out, Ada is unable to process her own trauma, feels insecure about the world, yearns for an Istanbul that is possibly nowhere as exhilarating as she wants to believe, and cautiously considers the fact that the country she knew might be gone forever. Her intuition was right, but her emotions spoke a different language.

As someone who has spent half of his life in the art world, and roughly a decade thinking and writing about art in Turkey, I am still not convinced by the metaphor of art in the novel, and there are very few moments in it where art is actually truly the medium — there is however an intoxicating scene about photography, but I recognize the process that the author had in mind: I left the country a few months after the Gezi park protests and sought refuge in the art world in different cities, from New York to Beirut, and ultimately returned to Turkey with the hope that one might be proven wrong. I wasn’t. As the descent continues, so does the carnivalesque function of art, perhaps hoping stubbornly for a change of luck, or that somebody else will turn the lights off.