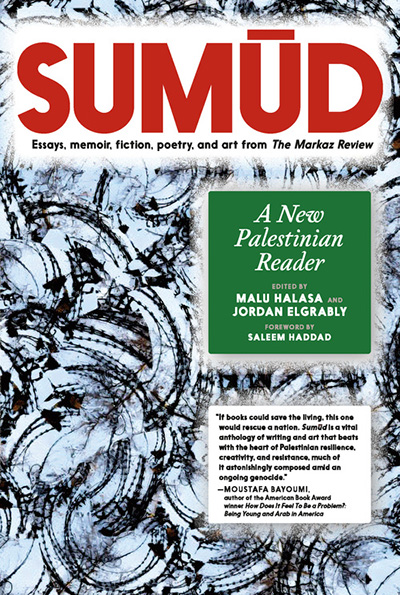

In this exclusive excerpt from the new book Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader, edited by Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably, chef Fadi Kattan shares several stories and recipes. The book’s co-editors have been on an East Coast tour for Sumūd, presenting it at Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania and NYU. Fadi Kattan’s newest restaurants are Akub in London and Louf in Toronto.

Fadi Kattan

Beloved Mansaf, Jericho Sheikh Daoud and the Battle of the Chicken

When I think about food and incarceration, the stories of the late Palestinian community leader Daoud Iriqat immediately come to mind. He was always a lesson in optimism and perseverance, carrying his political ideals high and proud through the shifting sands of our regional history. Spending long years in prison and then more in exile, food represented his sense of identity as well as his intense longing for home. However, at times his pursuit of food behind bars was itself all-consuming; it was a practical necessity, a matter of life and death.

Daoud’s mother was from an old Jerusalemite family, while his father was a landowner in Abu Dis, so he grew up between the city and the village. As a young man, he was religious and would go to pray at Al-Aqsa Mosque. Because his friends and peers were not religious, they would often taunt him, calling him “the Sheikh” — a nickname that followed him throughout his life. He liked to joke that his parents had sent him to Egypt to study theology at Al-Azhar and had expected him to come back a scholar, but when he got off the bus, he was carrying an oud and singing.

When he would walk around Jerusalem, Daoud’s elder brother, Ahmad, who was a teacher and an intellectual, would task him with distributing the Communist Party’s newspaper. He started reading the paper and discussing it with his brother. Thus, he shaped his own communist Leninist ideology.

Daoud joined the Jordanian Communist Party in the 1940s and, after the party split, stayed on in what became the Palestinian Communist Party.

He famously used to tell his family a phrase that encompassed his entire relationship with food: “I hate the empty plate!” It was a refrain pinched from his mother, who, like so many Palestinian mothers, was an accomplished cook and generous host.

Daoud’s memories of food were dominated by his mother’s sumptuous mahshi, “stuffed vegetables.” In Palestine, Jerusalemites are well-known for the different mahshi they prepare: zucchini, eggplant, vine leaves, cabbage leaves, and so many more. However, Daoud’s favorite meal was mansaf, that hearty dish shared in Jordanian and Palestinian traditions — melt-in-the-mouth lamb in a tangy fermented yogurt, served with rice.

But mansaf was something that Daoud could only dream of after he was imprisoned in Jordan’s Al-Jafr prison in 1957. He was condemned to sixteen years: one for participating in a demonstration and fifteen for being a member of the Communist Party.

Imagine how it must have felt for a man who thrived on culture, music, and eating well to be in a prison in the harsh, barren desert.

Very quickly, as Daoud would recount, he and the other prisoners focused on what they saw as the necessities of life: education, food, and alcohol.

They organized themselves to teach classes of party politics, languages, and music. For musical performances, Daoud dried the shell of a squash and made an oud out of it.

However, improvements in food required more imagination and hard work. The rations the prisoners were given were low in protein and iron, and they had begun to feel the deficiencies. This motivated them to carry out what they called “the chicken operation.”

A driver came regularly from Amman with stocks for the jail, and the inmates managed to pass him some money to buy things for them. They ordered fertilized chicken eggs and then set about building egg hatchers with cardboard and other scrap materials — anything they could lay their hands on. Finally, when twenty-eight eggs arrived, Daoud and his comrades attended to them on a relay system. They were elated when these hatched into twenty-seven healthy chicks.

Meanwhile, an agricultural engineer who — conveniently — was in jail with Daoud had managed to grow fasouliya (“green beans”) and a few other vegetables.

As the prisoners had no access to utensils, oils, or spices, they improvised. They used any metal tin to soft-boil eggs while the chicken meat was often boiled into a broth and eaten. When any fasouliya had grown, they would celebrate with a delicious fasouliya and chicken soup.

Then came the great setback for the prisoners: what was known as Al Maraket Al Jaj, “the Battle of the Chicken.” The prison warden had witnessed the great success of the poultry farm and, most probably getting no fresh meat himself, demanded a chicken from the inmates. After a meeting, the prisoners collectively decided to oppose the move, which they saw as pillage or extortion. Daoud would recall how he tried to reason with them — reminding them that they were ultimately powerless — but it was to no avail.

When the warden was told he could not have his chicken, he raided the farm with his guards and confiscated all the birds and the prisoners’ books. To add insult to injury, he broke Daoud’s oud.

Not to be deterred, the prisoners restarted their chicken project from scratch. It was an endeavor that continued until they were released.

Despite all the tremendous creativity and efforts of the jailed men, alcohol was always much more difficult. On only one occasion, after a long, drawn-out process, did they ever manage to distill one bottle of an alcoholic drink. Daoud would call it — one imagines euphemistically — arak.

He always remembered the heady party the prisoners had, fueled by that single bottle, and the sound of his new oud echoing across the vast desert late into the night.

Freedom finally came in 1965, when King Hussein of Jordan issued a pardon for the Communists of Jafr prison. All of the comrades were allowed to return home.

For Daoud that meant moving to Jericho to be with his family, and when he arrived back it was clear how they would celebrate: with lashings of the mansaf he had so desperately missed.

However, freedom did not last.

Less than a decade later, in 1974, Daoud was arrested once again, this time at his home in Jericho by the Israeli forces. He was to be punished for having signed the petition recognizing the Palestine Liberation Organization as the sole and unique representative of the Palestinian people.

But instead of imprisoning Daoud, the Israeli soldiers forced him across the Lebanese border, sending him into exile. His provisions — which he had at first refused — were only a sandwich and an apple.

After some time, Daoud made it to Beirut. A year later, he settled in Damascus. Amazingly, in Syria, he found ways to get sent some of the distinctive flavors of Palestine: salty Nabulsi cheese dotted with nigella seeds, pungent za’atar, and even fresh guava. But throughout his exile, he would complain of missing the huge, juicy pomelo from his garden in Jericho.

Daoud’s second homecoming was not until 1993. Once again, he was welcomed back with lovingly prepared mansaf.

Until his untimely death in 2020, the large table on the Sheikh’s terrace in Jericho was always a place to delight his guests with his favorite foods — and to serve up food for thought. His belief in humanism, universality, and the equal division of wealth between citizens and between countries, as well as his staunch fight for critical thinking and education, always endured.

His morning ritual was a sacrosanct time when he would listen to the radio and run an ongoing commentary with his lashing tongue while sipping his Arabic coffee. But Daoud’s gatherings always revolved around lavish meals; he believed in the power of delicious tastes and flavors to bring people together. It was always an honor to be invited to his home, but the greatest honor came if he really liked you. Then it would be your turn to be treated to mansaf!

Gaza Fatteh: Food from Home

Food memories are a tricky thing! It has been so long since I’ve been to Gaza, yet I still have wonderful memories of the Gaza fatteh prepared by the late Im Khader, my uncle’s mother-in-law. In my childhood memories she was quite possibly the best cook in Gaza — an impressive woman who prepared delicious feasts, had the best shatta recipe ever, and was also known for her celebrated lamb meat.

For non-Arabs unfamiliar with traditional fatteh, it’s a popular dish of toasted and often crumbled pita covered in diverse toppings, depending on whether it’s prepared in Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan, or Syria. Sometimes it’s simply pita covered with chickpeas and yogurt (in the vegetarian version), but there are also varieties made with chicken, lamb, or beef.

When I delve into my food memories around the Gaza fatteh, I still feel the combination of that first mouthful of rice, bread, meat — very deep, intense, earthy — and the refreshing piquant of the dugga (or dukkah, similar to za’atar, albeit made with nuts and spices rather than sesame seeds).

There was always the Gaza dugga but also, always at my aunt’s house, a few green chilies on the lunch table. Gazan cuisine is very different from Bethlehemian cuisine, bringing with it that marine air, that spiciness of the chilies and the long meals on the coast always rounded off with an unctuous mouhalabiya served with date jam.

Those memories of more than thirty years ago seem so unreal today.

Fatteh Ghazawiya

serves 8

meat & broth

8 pieces of lamb meat with bone (each 250 g) 10 cups water

2 tablespoons olive oil 1 onion, quartered

4 garlic cloves

2 bay leaves

2 teaspoons black peppercorns 10 cardamom pods

2 cinnamon sticks

1½ teaspoons allspice berries 3 teaspoons salt

rice & bread

2½ cups short grain rice 2 cups water

1 cup strained broth

2 tablespoons ghee

3 shrak bread or rkak

dugga

2 garlic cloves

6 fresh red chilies

5 teaspoons lemon juice

garnish

1 cup almonds

2 tablespoons pine nuts

method

for the meat and broth:

In a large pot, heat the olive oil, slightly cook the garlic and onions, and then brown the meat.

Add the spices and toss the meat well.

Add all the spices, cover with water, and bring to a boil.

Reduce heat, cover, and let cook for an hour and a half.

When ready, taste the broth and add salt to your liking.

Strain the broth to use both for cooking the rice and for serving.

for the rice:

Soak the rice for 30 minutes.

In a pot, melt the ghee, then add the rice and stir for a minute or two.

Add the water and strained broth.

Once the liquid boils, reduce the heat to low, cover, and let cook until the liquid is absorbed.

Fluff the rice grains with a fork and reserve on the side.

for the nuts:

In a pan, fry the almonds and then the pine nuts separately.

Leave each one to release the excess oil on a paper towel.

for the dugga:

Peel the garlic and chop off the heads of the chilies.

In a mortar and pestle, pound the garlic and chilies with a pinch of salt until you have a rough paste.

Add the lemon juice and salt to taste.

serving

Preheat your oven to 180°C (350°F)

Tear the bread into large pieces and toast in the oven for a few minutes.

On a large serving plate, arrange the bread and soak with the broth until the bread has absorbed the broth.

Add a layer of rice over the bread.

Arrange the meat pieces over the rice.

Garnish with the almonds and pine nuts.

Serve the dugga on the side for people to sprinkle to their liking.

An Oral History of Mouloukhiya (1)

Mouloukhiya, that magic verdure, hated or loved across the shores of the southern and eastern Mediterranean, is an abundant green herb that often ends up in a stew with varying consistencies and a long history of conflict. We hear words in a multitude of dialects: Warak willa na’ma? (“Leaves or chopped?”) Basal o khal willa basal o leimoun? (“Onions and vinegar or onions and lemon?”) ringing in conversations about this divine stew. But to the eyes of the uninitiated, mouloukhiya looks like a deep green stew that is viscous and many times repulsive. Why do we celebrate it to an extent that it becomes cult like!

Across Palestine, mouloukhiya is prepared differently, from the chopped tradition served with rice to the whole-leaf tradition served with bread. Then come the subtleties: With meat? With chicken? With rabbit? And the fine details that are game changers are the tasha garlic or garlic and coriander; do you place a tomato in the stew to remove the viscosity or do you leave it? In Umm Al-Fahem, mouloukhiya is cooked whole and served with khobz, “bread,” to dip in; in Jericho, it is chopped and cooked with generous amounts of chili and garlic; in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, it is cooked either whole or chopped with lamb meat or chicken and served with chopped onion in vinegar or chopped onion in lemon juice.

And the essential questions: Do you cook mouloukhiya only in season? Do you dry it? Or do you succumb to modernity and freeze it? For me, the dry and fresh mouloukhiya are two different experiences, each rich in flavors and creating two different memories: one of the celebration of summer and the other of a winter stew cooked with a combination of the nostalgia of sunshine and the smell of the mouneh room (a pantry where all produce was stored and where the smell of the dried mouloukhiya would reign).

When I remember mouloukhiya, I have this memory of a dark room where I could smell the dried mouloukhiya, but I still cannot remember if it was in Sido Nakhleh’s house or Teta Julia’s house or maybe both. And yet I remember the serving of the mouloukhiya, in a celebratory ceremony, with the right soupière for the stew, the long dish for the rice, the small bowls for the toppings, and then the soup plates, the generous spoons, and then the happy nods from everyone around the table when asked if they wanted seconds. I also remember Khadra, a woman who worked at my grandfather’s place, sitting with my great aunts Victoria and Regina, cleaning the mouloukhiya off its stems, on the terrace overlooking Bethlehem. I also remember when my aunt May, from Gaza, taught me the love of green chilies served next to the mouloukhiya and the sound of the crunching when you bite into one, the mixture of flavors, the quite earthy mouloukhiya, the rice, the acidity of the lemon and the vividity of the chili scent. As much as I enjoy cooking mouloukhiya, I have to confess that when I want to enjoy mouloukhiya, I ask my mother to prepare it. Her mouloukhiya renders the initial Arabic sense of a royal dish to the utmost — the fresh coriander and the garlic, the fried bread, the wise dosage of the stew is like no other.

As a chef rethinking Palestinian cuisine and focusing on highlighting local produce using untraditional methods, the plethora of preparations for mouloukhiya challenges me to explore its texture and the possibilities. The simplest game changer was frying the fresh leaf in a shallow hot-oil bath and serving it as chips, with a dash of salt or with a dip made of the traditional vinegar and onion but whipped into a creamy consistency, a bit like an onion-and-vinegar mayonnaise. But my favorite is based on a traditional mouloukhiya recipe, where I create a rice ball stuffed with a bit of mouloukhiya and meat, serve it on a small portion of stew infused with lemon and vinegar, and top it with fried fresh cilantro and garlic — a bite-sized Loukmet Mouloukhiya!

•

Desire and the Palestinian Kitchen

Wait for her and do not rush. If

she arrives late, wait for her.

If she arrives early, wait for her.

— Mahmoud Darwish, “Lessons from the Kama Sutra”

•

When I think of desire in the kitchen, I think of that tingling sensation when one develops a recipe and waits… waits for it to translate from an idea into the actual preparation… then the cooking moment. Then the plating. And after that, the first time you taste it. And the first time you serve it and wait for the first guests to taste it.

Nothing more than that stanza from Mahmoud Darwish’s poem, put into music by the fabulous Le Trio Joubran, captures those moments of waiting. And yet he talks about a man waiting for a woman, not a cook in a dark kitchen waiting for a dish.

All through the ages, chefs were perceived as having somewhat strange personalities, huddled up in dark kitchens, often in noble or royal mansions, in the basement. They would conjure a sort of mystical, unholy magic to create dishes served with great pomp at the hosts’ table.

The desire to excel and then the desire to share the pleasure of the flavors with the guests and the world at large fill the chef with such anxiety that often they go mad. This pushes them over the edge and a frenzy of feelings and thoughts rush through the chef’s mind and nervous system in this instant where the culmination of the courtship of the dish and the deep desire to please.

Despite their airs of big bullies and insensitive beasts, chefs are a funny breed, mixing a lot of this authoritarian, quasi-rigid command in a kitchen while within themselves being, I believe, the most sensitive and fragile beings.

The art of the table is close to the Kama Sutra — despite its different relations, protagonists, and elements, they are similar in the rhythm and the wait; the build-up and the tension; the meeting of flavors, textures, and soul in a dish; the reveal of the final dish and then the pleasure; the chefs become the creators and at the same time the naked souls waiting for the pleasure of sharing with others an illumination. Desire is an expression of many states and contexts, and yet in the kitchen, they morph into one — the desire of a mother to share nourishment with her child, the desire of a lover to seduce, the desire of a patriarch to ensure the perpetuation of a craft, the desire of a child to have fun, and the desire of longing to recreate a taste from nostalgia with the intense yearning to create for the future an enlightened idea, all wrapped up into a small vessel, a dish, a plate, a bowl that contains all those desires.

And the desire for beauty! Which chef does not try to arrange, prepare, dress their plate in its finest? Which chef does not agonize before a rendezvous about the choice of the outer layer of their dish, about the finest details of the vestment and the most precise detail of the garnish? Which chef does not, in a moment of folly, sense that their dish does not look good enough for that rendezvous and in that instant let their primal cravings run wild in deconstructing the dish, splashing the sauce in a fit worthy of a desire-struck creator?

—July 15, 2021, to March 15, 2022

(1) From “An Oral History of Mouloukhiya from Egypt, Palestine, Tunisia and Japan,” by Fadi Kattan, Nevine Abraham, Ryoko Sekiguchi, and Boutheina Bensalem, Markaz Review.

Hailing from a Bethlehem family that has on the maternal side cultivated a francophone culture and on the paternal side, a British culture as well as a demonised and ostracised daughter/step-daughter/half-sister to Fadi/Karim & Muna Kattan. Whom by colluding together they have mentally & emotionally destroyed. Born as she was, after their father, when a law student in London. As my then boyfriend, he violently raped and impregnated me after also seducing my best friend. Fuad Kattan then gaslighted me to make me believe that I was equally to blame for my pregnancy. He also bullied me in the registry office, not to add his Kattan surname to his beautiful doppelgänger daughter’s birth certificate. He then abandoned us with zero financial support. When his daughter went alone to Bethlehem, twice, when a teenager. Fuad & his first cousin of first cousins wife: Micheline told her to get lost! As can be read about in her poignant online article: I Went to Bethlehem to find my Father – by Liza Foreman. Liza also liberated Fadi Kattan from his loathed Dean of Business Studies at Bethlehem University. As she was so desperate that she wrote to the kindly Chancellor, to ask him if he could persuaded her father: Fuad Kattan, as Chairman of the Board of Trustees & Fadi to have contact with her. These two charmers resigned rather than do that. Up to then his controlling mother: Micheline Dabdoub-Kattan, had stopped Fadi fulfilling his dream of becoming a chef. Now, at age 35+ Fadi finally grew a pair & became a chef. All thanks to his weaponised half-sister. Who also suffers from intractable insomnia & can’t work full time as once Variety’s Chief EU correspondent. So she is virtually homeless in central Paris, where Papa dearest allegedly owns 2 luxury apartments. The Kattans all know this & care less. Despite Fake Fadi blathering on about how Granny Julia taught him to respect and revere all women! As the astonishingly brave Gisèle Pelicot says: Shame must change sides. The Kattans are, to me, a despicable family. Shame on them….