On not wearing a dress—a girlhood between Syria and England.

Rana Haddad

Before I was born my father had decided that I was going to be a boy and had already named me Abdullah. This was the name of his father, whom he adored, and who had passed away two years earlier. My father was the eldest of three brothers and a sister. He wanted to be the first to have a boy, to father the son who would take on his father’s mantle. This was not an easy mantle to have thrust upon the new boy who was yet to be born, for my grandfather had been a macho colonel in the Syrian army under the French Mandate (and after Independence); strict and disciplined but also possessed of strong literary sensibilities; a writer of poetry and a voracious reader who inspired respect in all who met him. The perfect patriarch.

When I was born, at only eight months old, “the size of a chicken,” as my father later told me, what a surprise it was to him that I turned out to be a girl. Instead of allowing himself to be disappointed, he simply began to treat me as if I were that boy whom he’d always dreamt of fathering. My being a girl was a small detail, easy for him to ignore, particularly as I turned out to be the kind of girl who found the prescribed lifestyle of girls of that era of no interest. I was only too happy to oblige him his fantasies; I was a boy manqué.

He was a very gentle, kind, entertaining, storytelling and playful father, who sang in the mornings, and drew on napkins and made paper airplanes out of the gold and silver linings of his Al-Hamra cigarette packets. He was the opposite of a soldier, more of an artist (only inheriting the artistic side of his colonel father, who was able to combine the military with the literary). He’d wanted to be a sculptor in his youth but had been pressured to make the more sensible career choice of becoming an architect.

He often gave me father-to-son advice, such as, “If any boy ever tries to punch you, just punch him back, even harder. You’re my daughter and you’re going to be stronger than any boy. Show them what you’re made of!” I listened with great curiosity but didn’t follow his counsel, as my instincts didn’t spur me on to punch boys, nor did any of them (thankfully) attempt to punch me. I enjoyed playing tomboyish games with them, Cowboys and Indians or Thieves and Robbers, and making up stories of characters and adventures that we’d play out over days and months and sometimes years to come. I befriended these boys at school, at the beach and even sometimes on the street outside the garden gates of our house, where I developed a working relationship with two street vendors who sold Coca-Cola. Their names were Shadi and Hamoude. They would let me sell the Coca-Cola or 7-Up or Orange Crush bottles on their behalf, so that I could experience the head-spinning joy of collecting money from customers, which seemed like such a very grown up thing to do. This continued for a few days until our neighbors reported me to my parents with horror, and an end was put to my antics. It was not considered socially acceptable for a man belonging to the professional classes to allow his daughter to work side-by-side with feral street boys. The expectation was that I should stay at home and play with dolls and not roam around in the streets like an urchin. Other girls seemed to find such a thing easy, but to me it felt like a terrible restriction.

I was keenly aware of the city around me, rather than only of our small building where we had two sets of neighbors. I wanted to discover the deeper entrails of our city, including the fish market, the fruit and vegetable market, the old harbor and the new harbor.

I imagined that if I were a boy, I’d be allowed to do this. I watched other girls in our building stay put in the confines of the garden while often playing at being a housewife or mother or princess; all roles which I found too dull and quite depressing. I wanted to be a pirate, a thief, a red Indian, a cowboy, a sailor, an astronaut, an archeologist, a fantastic figure from a book of adventures, perhaps even an inventor, all roles I was able to play at high intensity with neighboring boys, who also had wild imaginations and an unrestricted desire to do anything.

Under the pretense that I was playing at a neighbor’s house, I would sometimes slither out into the fish market or the old harbor without asking for permission or telling anyone about it. I’d spend hours in antique shops looking for a magical lantern. I’d buy old ceramic and pottery oil lanterns with my pocket money and try to test them back at home, to see if they would work. I bought the sorts of long slim baskets that local mountain hunters used to store their arrows in, and discussed with carpenters how much wood it would take and how much it would cost to build a tree house. In our neighborhood and on the beach, I played with mud, I built tents, I ran amok, I wore shorts and a t-shirt and a bikini without a bikini top, I had an androgynous ’70s haircut, I looked scruffy and unkempt. And for that I was called a Tom Boy, or Boy Hassan, which is its Arabic equivalent.

Whether at school or outside, I was considered an honorary boy by my many “boy” friends for years, until my body began to change and I could no longer hide the signs of being female. It was about that time that all the boys were unceremoniously sent off to a boys’ only school. It was considered strictly necessary for them at that age to stay segregated during set hours of the day to avoid them being softened and distracted through the company of girls. Except for me, who stayed behind at the Carmelite’s Private School for Girls (which was originally a convent school built by the French who had turned our Byzantine and Ottoman heritage sea-side harbor city of Latakia into something with the flavor of Marseille). Although we were all girls, we were still forced to wear the compulsory school uniform which was a miniature military outfit, no skirts allowed. So far so good.

My father’s idea of being a man was very simple and pleasant. He had grown up during an era when men felt free to smoke from morning till night, drive fast, punch one another for minor infractions, and even kick people out of the door, literally, with a foot on the ass, if they didn’t like them or found them or their opinions annoying or distasteful.

Although I had never witnessed such actions with my own eyes, I’d heard that he had once or twice expelled a client who had infuriated him, by kicking his backside and throwing him out into the office landing: “Out, out,” he’d shouted at him. The client’s offense had been to insist that my father design two separate entrances, one for women and another for men, for the building he’d been constructing for him. This was a time when men of his generation all over the world watched American cowboy and mafia films such as The Italian Job, in which Michael Caine threw punches at other men, slapped women’s bottoms, and smoked like a chimney. To me at that age it seemed like fun to be a man, so unrestrained, so “unladylike,” so free to be loud or rude, silly or bold. Meanwhile, being a girl seemed laced with the necessity of being nice at all times, polite, considerate and demure. If playfully slapped on the bottom by a man, a woman was supposed to laugh rather than slap him back. I felt that something was not quite right, but I had no words to describe it. Men were allowed to be sinners, women expected to be saints.

I have no idea whether my father’s decision to consider me a son was the reason I felt strange wearing a dress. From quite a tender age, every time my mother tried to put me in a dress I refused, except on rare occasions, such as sitting for professional photographs taken at our local photography studio, or during my aunt’s wedding or other ceremonial occasions. I did it grudgingly, until the time I declared to her that I would simply never wear a dress again. From then on, every time she tried to persuade me to wear one I would not accept, until it became a battle of wills: wearing a dress would have meant I’d lost that battle. Being very stubborn, losing any battle of wills with anyone, let alone my own poor mother, was not even an option.

“What man will want to marry a woman who doesn’t wear a dress?” she’d say while sitting around in one of her floral dresses that made her look like a flower waiting to be plucked and then put in an expensive vase. And I’d reply, “A man who loves me regardless of what I am wearing, a man who is not looking for a doll.”

“There is no such man,” she’d say. “Men want to have a beautiful wife and in order for a woman to be beautiful she needs to dress in a feminine way. This is how the cookie crumbles,” she’d inform me at regular intervals. She’d learned such expressions in her American school in Singapore, where she’d been trained, arguably indoctrinated, with a 1950s post-war ideology of womanhood. Although she was Dutch and therefore western, my mother in those years was more sexist than the women of our Syrian neighborhoods, some of whom worked as businesswomen or in the local banking sector or as teachers and head-teachers, lawyers and sometimes architects. In her mind’s eye, a good woman was destined to be someone’s wife. She was also more importantly a woman who found such a dream and destiny absolutely fulfilling with every fiber of her being. A woman who had dreams and ambitions beyond those of homemaking, looking good and raising children was not “a real woman,” I was told. This is how she’d been raised by her own mother (an Armenian from Dutch Indonesia) and by her father who had left the Netherlands after it fell to Nazi occupation in 1940. It was at that time, hearing those thoughts that had been handed down over generations from a multitudes of countries, eras and cultures, that I began to hear of this concept of “being a real woman.”

It sounded like very hard work.

Somewhere in the back of my mind I felt that wearing a dress would be like wrapping myself up in pretty packaging, waiting to be picked out by someone whose mindset was like that of a shopper at an exclusive store. I didn’t aspire to such a fate, and felt that wearing a dress would be to admit defeat to my mother’s ideology — to agree that I would never be loved for myself, but only if I were packaged and marketed in a way that would appeal to the highest bidder. From a young age, I unwittingly resisted that narrative. I decided that love must be something that came to me from someone’s heart or what I believed even at that time was their soul and that it should not depend on roles or on costumes or what I in those early days saw as “theatre.” Was there a man who was not a “shopper”? I was not sure, but I was determined to insist on such a man, and to refuse or repel any other.

I saw a dress as a symbol of agreeing to wear the costume of femininity, and I developed an allergy toward it. Although this was during the early nineteen seventies, in a small town on the Eastern Mediterranean where the nascent ideas of feminism had not yet begun to infiltrate, these feelings arose in me spontaneously, unprompted. I had no name, nor context for them.

Meanwhile every morning, while my quite macho father was shaving, he would sing songs by female singers such as Fairuz or Taroub from the point of view of lovelorn women. His favorite was “Ya Sitti Ya Khityara”:

Oh Grandma, my old Grandma,

you who are the ornament of the entire neighborhood,

my lover whom I love is waiting for me in his car.

I love him, I love him, I can’t hide it,

and his eyes have turned my heart into cigarette ashes,

shall I wear my green dress or shall I wear my red dress?

I don’t remember if I ever found it strange that this was my father’s theme tune. He sang it every morning and sometimes in the afternoon while he peeled an orange to eat after lunch.

There was a part of me (if I were honest with myself) that wished I could be the kind of girl he was singing about, someone who naturally desired to wear such dresses and who had a collection of them in her closet ready for every occasion. Deep inside, despite my outward stubbornness, I was quite nervous, for I knew that I’d have to pay a heavy price for not being such a girl.

Could it be that perhaps I was a boy after all, a boy at heart? Real girls were naturally drawn to girlish things, they loved buying and choosing dresses, they loved dressing up and dressing their dolls up, they loved to play at wearing make-up and enjoyed collecting necklaces, and bangles and beautifying themselves. These activities and concerns fascinated and attracted them, whereas living that way made me feel like a cat trying to pretend it’s a dog, or a duck trying to pretend it’s a hamster, or some other very uncomfortable attempt at impersonating someone one is not. I imagined that if I wore a dress and looked at myself in the mirror what I would see would be a boy in a dress. I could not do it.

One day I went to the cinema with some friends and saw a Russian film about a boy who discovered a box of matches with magical powers. The box had only a couple of matches, but, upon lighting them, the boy could make a wish and it would come true.

That night, before going to bed, I imagined what I would do if I could get my hands on this box of matches. What would be my first wish?

To wake up a boy.

What would be my second wish?

That everyone who ever knew me would only remember me as a boy?

In the mid 1980s we moved to England; by then I was fifteen years old. Dressing up as a tomboy began to cause me untold social distress and I noticed that indeed the road to romantic love with the opposite sex was not going to be an easy one for me. At fancy dress parties I dressed up as a clown in a suit, baggy trousers, a red nose and a large blonde wig. I wanted to hide my girlness and find an excuse to wear a suit and smoke a pipe. I didn’t want to be Simone de Beauvoir, I wanted to be Sartre. I wanted to be the First Sex, the protagonist, the subject of a story, or a life, not the object.

I remember as I headed out to the party how my grandmother who lived in England looked at me. “Who will marry her?” she whispered to my grandfather. Meanwhile my sister and friends turned up dressed as femme fatale Cleopatras or princesses or pop starlets, looking every inch the glamorous girls any boy would have effortlessly fallen for. What sort of boy was going to ask me, a clown, to dance?

In England during those teenage years, the aim was not to receive a “marriage proposal,” as it would have become after the age of seventeen or eighteen had I continued to live in Syria; the aim was to be asked out by as many boys as possible or to be kissed by random boys in parties or nightclubs. Girls competed in dressing in such a way as to attract that sort of attention.

Meanwhile, I was getting letters from my friends in Syria who had gone full boy crazy and began to dress like Egyptian film starlets, dying their hair blond, wearing extreme make-up and the best dresses money could buy. I was still unable to change my ways and insisted on wearing a dull uniform composed of a pair of cream-colored corduroy trousers or baggy jeans, long knitted jumpers or t-shirts. And not a spot of make-up.

The lectures about the necessity of wearing a dress, by my mother or my grandmother, continued to be delivered at regular intervals along with concerned looks and heavy sighs. I became shy and I no longer imagined I could be a boy. A young woman is far too different from a young man. My voice was soft, my skin was soft and I was not six-foot tall. I had no interest in all the things I noticed English men were interested in: Football, loud music, motorbikes, money. English concepts of femininity and masculinity seemed very different from their Syrian counterparts and even more alienating. They were described and proscribed at great and lurid detail in magazines the like of which we had never heard of back in Syria, magazines such as Just Seventeen and Cosmopolitan, which gave detailed instructions about how to perform a selection of sex acts and how to apply make-up and dress to make oneself irresistible to the average joe. This also sounded like hard work.

Being a boy was different from being a man. I did not want to be a man. By now the charm of maleness began to fade and it felt like something very different from who I truly was. However, the eternal boy whom I imagined still lived within/inside me continued to find it impossible to wear a dress and did not know how to express himself without getting into trouble.

A part of me began to wonder why I was making such a spectacle of it. Perhaps one day I should try a dress on, I thought to myself. But not today, not tomorrow, and not the day after. I waited for that day to come, the day that I’d want to wear a dress without feeling forced to. Meanwhile, I distracted myself with reading an endless number of books. I decided that I was an intellectual, intellectuals were not superficial people and should have a licence not to wear dresses, or this is what I convinced myself.

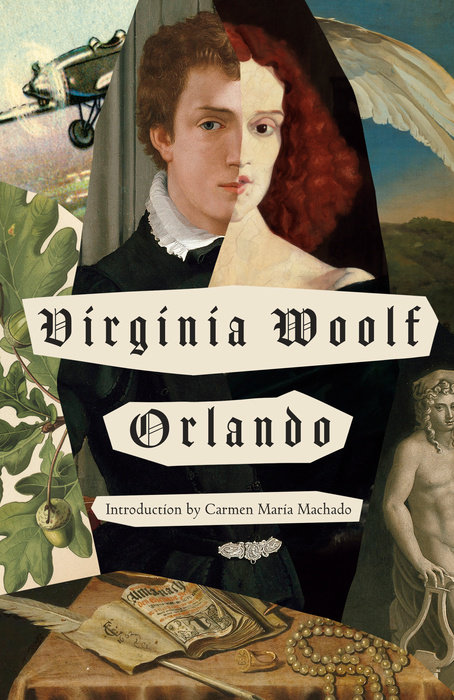

Salvation: Virginia Woolf

When I read Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for the first time, I was seventeen or eighteen years old. It was perhaps the first full-length novel that I’d read in English, which I’d begun to learn at the age of fifteen. I couldn’t stop reading it and had to spend three or four days in bed after finishing it. I developed a sudden inexplicable flu while paging through it, possibly caused by the sensation of reading too fast, not being able to breathe while reading, feeling almost faint from exhilaration.

It was the first time I’d read a book that described a human being who was somehow able to live as both a man and a woman, alternating between the two and thus experiencing the true fullness of being human. They were not being artificially restricted to one aspect of their nature but were both active and passive, dressing in every type of outfit, socializing in the different ways society allows for each gender, loving both women and men, dressing as both men and women and seeing the world from every point of view. The catch was that this was only possible in a sort of science fiction setting and over the span of four lifetimes, lived over the span of four hundred years of history.

Here lay in my hands at last a chronicle of such a life documented in great detail within the jacket of a novel written forty-two years before I was born. I could scarcely believe that Virginia Woolf, who had lived and died in a country that I’d not known much about in my early years, and who wrote in a tongue that I was only vaguely familiar with, had written a novel to describe a human being who lived life the way I had always felt it.

Never before then had I read a text that conveyed the strange feeling that had accompanied me since birth. It was the feeling that deep inside there lived both a girl and a boy, alternating within me. Now that I was older, they had turned perhaps into a young woman and a young man. I understood then, that feeling inside me, and for the first time it felt like freedom. The imposed restriction of having to only live as one gender and according to how society had allowed that gender to experience life was something that had been strangling me and “cramping my style” from a very young age. It felt like only being allowed to live half a life, not a full one; a life in two dimensions, rather than three or four or five. I had no words to articulate this feeling of frustration and incomprehension until I read Orlando.

Maybe if I hadn’t been told again and again how I must feel, dress and be in order to qualify to join the club of my own sex, I would have been able to relax and not beat myself up for those qualities I possessed that didn’t fit into the costume drama that had been woven in my head: the drama of being only half of what I could be.

One summer in London, while on a summer’s break from university, I finally went into a department store and I bought myself a pistachio-coloured silk skirt and a beautiful summer top. The next day I walked out of the flat where I was staying with family friends and noticed how different the world suddenly seemed. From the moment I went out of the door, I noticed that I had to walk slower, that I was too visible, and that too many eyes were on me. I enjoyed feeling prettier than I usually did, but I also hated it. After two or three weeks of that paradoxical experiment, which on the whole was too stressful, the pistachio colored skirt and another stylish skirt that I’d also bought went back into the cupboard, never to be worn again. I realized that wearing a skirt or dress did indeed require qualities of me that I didn’t possess: the ability to protect myself from the attentions of random men, most of whom I had nothing in common with and who only saw me as a woman, not as the full spectrum human being that I knew myself as.

Over the years, I lost the desire I once had be a boy or the secret wish that I could be more of a girl. I accepted that I was a human being who didn’t like to be told what to wear or how to be. And not only that, I also found myself, after returning to London, falling in love with men who had long hair and were beautiful and sensitive and women who were bold, unconventional, wild and rebellious. Both sides of my nature found a way to express themselves. But I never did acquire the skills necessary to play the socially prescribed roles of either a woman or a man.

•

Six months ago, I moved to a new home in Athens on the fifth floor of an interwar building in the center of the city, built in 1938. In the entrance I found a stained-glass window of an androgynous minstrel. Visitors ask me: “Is it a boy or a girl?”“Perhaps he’s a boy who looks like a girl or a girl dressed as a boy. I don’t know.” At the end of the day what really stands out is his or her mastery of the lute. What he or she wears does not define them.

And being both is the culmination of “the best of both worlds.” That is if you’re willing to pay the price of being part of both but belonging to neither.