One evening in the mid-1990s, as tradition went, families in Lebanon gathered around their TV sets and mindlessly scrolled through the limited channels they had on offer. Little did they know, they were about to witness an episode in drag history — Alam El Fan (Art World), a famous talent show on the popular Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation (LBC), was about to see celebrity impersonator Bassem Fegahli take to its stage, unknowingly trailblazing what has slowly grown to become a shining beacon of hope for all LGBTQ+ Arabs, Beirut’s drag scene.

“Drag as an art form, particularly female impersonation, has been in Lebanon for so long, in movies and arts,” says 26-year-old Hoedy Saad, a known veterinarian by day and a vogueing and drag mastermind by night.

“Bassem Feghali is the one we grew up watching, but he never came out as a drag queen. He would say he’s a female impersonator or a celebrity impersonator,” recounts Saad. “Of course he did do drag, but he couldn’t say it back then so that he’s not labeled as gay.”

Much has changed since; Lebanese drag queens and LGBTQ+ figures are now as visible and out as they can be, birthing what is arguably the Arab world’s only active drag scene. And while Feghali served as a main inspiration, the current scene came to life much later.

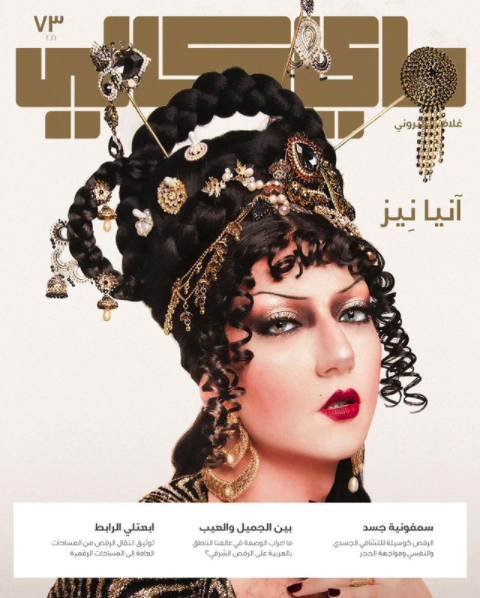

“Legendary queens Anya Kneez and Evitta Kedavra were the pioneers of the current drag scene,” says Saad. “It started with a few shows they did in clubs some 11 years ago, and up until four years ago, they were the only two on the scene.”

Today there are between 40 and 60 queens comprising the city’s vibrant drag community, with the real take off happening some four years ago, according to Saad, when he brought a Brooklyn drag tradition to Beirut, drag balls. In addition to serving looks and walking the runway, vogue dancing, a highly stylized modern house dance which was also pioneered in New York City’s drag scene in the 1980s, made its way to Beirut. Saad, being a dancer, pioneered vogeuing in the city, becoming the foremost vogue instructor until today.

Organizing the first Beirut Ball back in 2017 brought unprecedented visibility and vitality to the scene, ushering in a new era of what’s been dubbed by Vogue magazine “the Beirut Dragissance.”

“Here you can find every drag in the book; from comedy queens, dancing divas, look queens, club kidz, biological females — you can find anything. This is why Beirut’s drag scene is very unique and diverse,” says 25-year-old Moustafa Dakdouk, AKA queen Latiza Bombe.

Dakdouk, who in 2019 was featured in Vogue, took her first steps in the drag world some seven years ago, being embraced and taught the craft of drag by some members of Beirut’s trans community. An operational manager is her day job, but by night, a spooky queen comes to life. Unlike Saad, whose family struggled to understand but eventually embraced him, Dakdouk isn’t as fortunate.

“I’m not out to my parents as gay, let alone if they knew about drag; they would literally kill me,” exclaims Dakdouk. “I come from a very conservative family who I left at 17 to pursue my own independent life.”

The queens generally live in relative safety in one of the region’s most open-minded cities, however their lives are anything but void of fear.

“It’s a hustle to go out in drag to reach the venue, you can’t imagine the amount of stress and fear I live each time,” says Dakdouk. “And that’s just with my makeup on; no outfit or wig. We usually perform in very underground places that are kept on the down low, but after the explosion that happened on August 4 we lost them all,” adds Dakdouk, referring to the Beirut port explosion that shattered the city last summer.

The explosion was the final straw for a nation-wide economic and social crisis. Since the onset of the Lebanese revolution in 2019, the country’s volatile political situation intensified a severe economic crisis that sent the Lebanese pound plummeting to less than 90% of its pre-revolution value. This has impacted every Lebanese citizen as basic goods and services in the import-reliant country vanished off the shelves, and whatever remained became costlier than what the average citizen could afford. It’s easy then to imagine that seemingly secondary purchases like drag supplies were no longer easily attainable or remotely affordable.

“The economic crisis had a huge impact on the drag scene,” says Dakdouk. “We get paid in Lebanese pounds, yet we import most of our drag supplies from abroad. So suddenly everything cost 20 times what it used to. However this also made me reuse things I had before or try to modify them and create something new.”

This resilience and reinvention has always been a feature of drag communities in Beirut and elsewhere, and despite the political and social turmoil, the drag scene in Beirut continues to flourish and its members continue to bring much visibility and hope to Arab queer and drag communities. Unlike the 1990s, little gay kids from across the Arab world now grow up with many role models to look up to, not just western pop icons and gay figures, but rather Arab queens that share their heritage, culture and fierceness. To the Beiruti queens, this is what makes the hardships they encounter on a daily basis worthwhile.

Sadly, however, many queens, similar to the bulk of Arab youth, queer or otherwise, are looking for a way out of the country, risking bringing the vibrant scene to ground zero.

“It’s a love-hate relationship with Lebanon, but honestly I’d love to just travel outside the country,” concludes Dakdouk.

—Anonymous

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)