Rana Asfour

It can be argued that when Bahman Farzaneh translated One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, he introduced the Iranian community to magical realism — a literary genre especially associated with contemporary Latin American fiction. And yet the genre struck a chord with Iranian writers and filmmakers, who often deploy it in their work.

As storytellers, Iranian writers continue to create an “alternative world” where no outside rules apply in a bid for social commentary on historical convulsions and wrenching personal upheavals inside Iran that are rarely addressed without consequences. As each of these writers relies on a sense of novelty in challenging the imposed dominant contradictions between opposites — real/magic, traditional/modern, mysticism/religion and man/woman — to create works that are singular and non-conformist, they risk persecution and even death for what Iranian authorities consider subversive revolutionary texts meant to stoke unrest and sedition.

As storytellers, Iranian writers continue to create an “alternative world” where no outside rules apply in a bid for social commentary on historical convulsions and wrenching personal upheavals inside Iran that are rarely addressed without consequences. As each of these writers relies on a sense of novelty in challenging the imposed dominant contradictions between opposites — real/magic, traditional/modern, mysticism/religion and man/woman — to create works that are singular and non-conformist, they risk persecution and even death for what Iranian authorities consider subversive revolutionary texts meant to stoke unrest and sedition.

In an interview with The Punch Magazine, Shokoofeh Azar, author of The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree (listed below), said that one of the reasons writing a political novel was doubly risky for her as an Iranian was “because the Iranian regime does not like Western countries to understand how cruel this regime treats its own people,” and that there was always a risk of negative reaction to the book or herself by the regime which could have dangerous, far-reaching consequences. Her fears were confirmed when she was forced to move to Australia as a political refugee in 2011. Azar’s novel is banned in Iran and on the request of the author, the US-based translator’s name has never been released “for reasons of safety.”

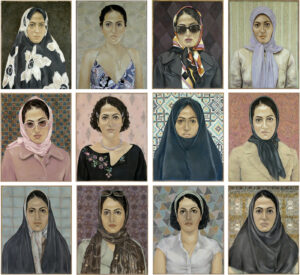

Similarly, Shahrnush Parsipur, who began her career as a fiction writer and producer at Iranian National Television and Radio, was imprisoned for nearly five years by the Islamist government without being formally charged. She published Women Without Men (listed below) shortly after her release and was subsequently arrested and jailed again, this time for her portrayal of women’s sexuality. While still banned in Iran, the novel became an underground bestseller in the country and has been translated into many languages around the world. She now lives in exile in northern California.

And it is not only Iranians who suffer the far-reaching tyranny of the Islamic Republic. Only recently, the world was reminded of Khomeini’s renewed 1989 fatwa against British-Indian Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1988) — a novel that was inspired by the life of the Prophet Muhammad. The author was attacked just as he was about to give a lecture at Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York, in August of last year. Ironically, Salman’s book is dripping with magical realism.

Shirin Neshat, an acclaimed visual artist from Iran, who adapted Women Without Men by Shahrnush Parsipur into a feature film, once said that magical realism allows her “to inject layers of meaning without being obvious. In American culture where there is freedom of expression, this approach may seem forced, unnecessary and misunderstood. But this system of communication has become very Iranian.”

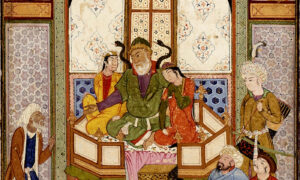

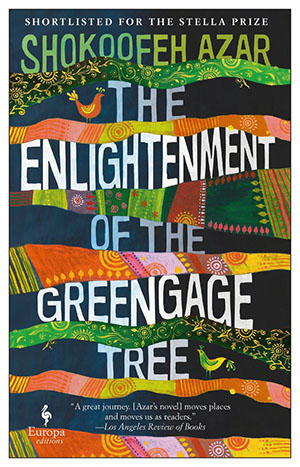

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar (2020, Europa Editions)

Shokoofeh Azar, the first Iranian woman to be nominated for the International Booker Prize and the first woman to hitchhike the entire length of the Silk Road, has written a heart-breaking novel that emulates the rich storytelling tradition of a bygone Persia.

Set in Iran in the decade following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, this moving, richly imagined novel portrays a bereaved family who seek solace in the ancient forests of northern Iran. Narrated by the ghost of Bahar, a 13-year-old girl whose family is compelled to flee their home in Tehran for a new life in a small village, they hope to preserve both their intellectual freedom and their lives. The family members soon find themselves caught up in the post-revolutionary chaos that sweeps across their ancient land and its people. The novel features magical realism and playful narrative as well as an extensive knowledge of Persian folklore to comment on the conditions in Iran today and the feeling of alienation in one’s own country. It is a novel steeped in mystical Iranian realism and poetry.

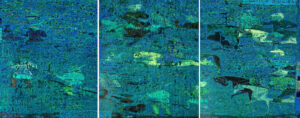

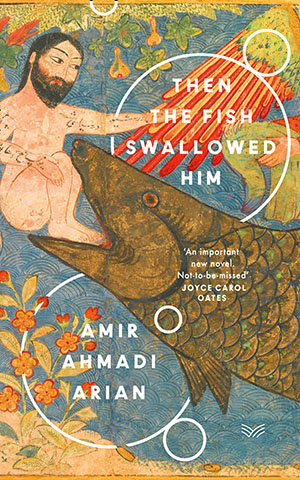

Then the Fish Swallowed Him by Amir Ahmadi Arian (2020, Harpervia)

Described as a “1984 for the twenty-first century,” Then the Fish Swallowed Him is an exposé of life in modern-day Tehran and a “timeless story of totalitarianism.”

The journalist and acclaimed author weaves a fantastical, propulsive and distressing novel set in Evin, the infamous political prison in Iran. Its latest resident, Yunis Turabi, a former apolitical bus driver in Tehran finally reaches a breaking point. Handcuffed and blindfolded he arrives at the prison to face his interrogator, Hajj Saeed. The two soon develop a psychologically disturbing yet interdependent relationship. In between extended bouts of solitary confinement and hours of interrogation, Yunis’s memories oscillate between his childhood and the betrayal of his closest friend, until he must decide whether he will keep on fighting the increasingly undeniable accusations, or submit to the system that upholds Iran’s power.

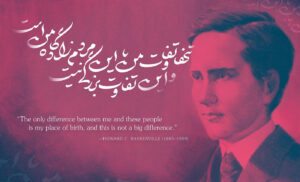

The Immortals of Tehran by Ali Araghi (2020, Penguin Random House)

A debut novel by award-winning Iranian writer and translator, Ali Araghi, that is at once an epic and multigenerational saga extending from WWII and Soviet invaders in Iran through the reign of the Shah, the Islamic Revolution, and the Iran-Iraq war that all continue to have political and social resonance today. The thread of magical realism throughout renders The Immortals of Tehran perfect for fans of Gabriel García Márquez.

The novel follows Ahmad Torkash-Vand who treasures his great-great-great-great grandfather’s every mesmerizing word. On the day of his father’s death, an incident that renders a young Ahmad permanently mute, he listens closely as the seemingly immortal elder tells him the tale of a centuries-old family curse and Ahmad’s own fated role in the story. Ahmad grows up to become a politician and in relative anonymity he writes rousing poetry, powerful incantatory words that the leftists inadvertently use to advance their cause.

Women Without Men by Shahrnush Parsipur, translated by Faridoun Farrokh (2011, The Feminist Press)

Against the tumultuous backdrop of Iran’s 1953 CIA-backed coup d’état, the destinies of four women, including a wealthy middle-aged housewife, a prostitute, and a schoolteacher, converge in a beautiful orchard garden on the outskirts of Tehran where they hope to escape the confines of family and society, where “it doesn’t make sense for a woman to go out in the first place. Home is for women, the outside world for men.” As these brave women look for solutions to their individual problems, they also find independence, solace and companionship. Without men.

Published in Persian in 1989, the novella reads almost like a fairy tale, drawing on elements of Islamic mysticism and recent Iranian history. Not unlike the Garden of Eden, this orchard becomes “a utopian island, a place of exile where women may take refuge, as long as they respect its rules … once inside the orchard we abandon all logic of time and place, and face the deeply existential and personal crisis of a few women,” as Shirin Neshat writes in the book’s preface.