“Gut Feelings” is on view at The Mosaic Rooms, the nonprofit art gallery and bookshop in London, until May 29th, 2022. Hayv Kahraman will give a free online artist talk from Los Angeles on April 7, 7 pm UK time. More info/RSVP.

Melissa Chemam

Provocative, symbolic, healing, feminist, the work of Iraqi American artist Hayv Kahraman is pictorial, yet anything but ordinary. Kahraman, who identifies as Kurdish, fled the U.S. occupation of Iraq, first for Sweden, then the United States. She has called Los Angeles home for the past 17 years. As The Mosaic Rooms curator points out of “Gut Feelings,” “the artist delves into scientific research to situate the effects of trauma in the body and to investigate methodologies of physical healing and care.”

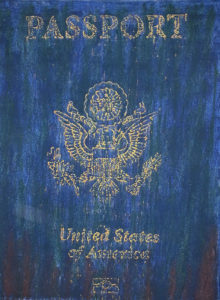

Kahraman herself explains: “I was cleaning out my mother’s belongings and found a book titled Neurosculpting. Did you know that you have the ability to physiologically recreate new neuropathways in your brain, to re-sculpt, to unlearn and relearn? Now imagine what that means for a refugee.

“I think about my own experiences as an Iraqi who fled the war to Sweden, and can’t help but notice an insidious regurgitation of pain that circulates in the migrant communities I belong to.”

Her “Gut Feelings” series occupies three rooms in order to tell us a story, and to take the viewers on a journey, a cycle of healing.

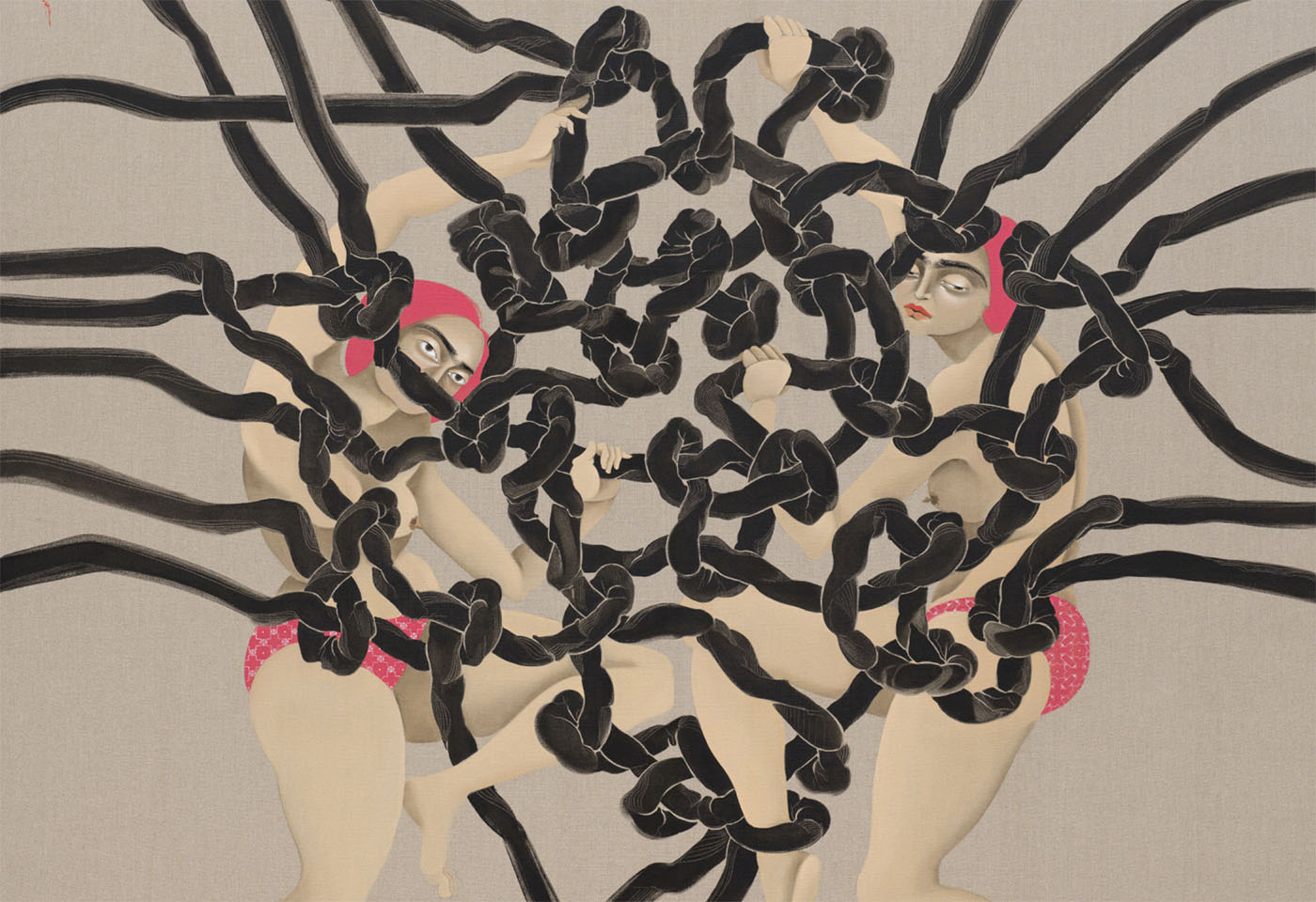

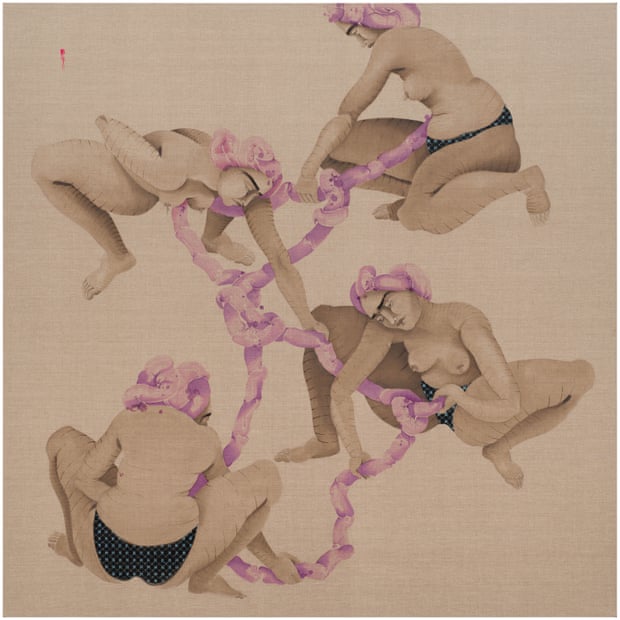

In the first room, the main painting represents four women trying to control or untangle mauve ropes linked by knots, in positions that can remind one of a dance, a ritual or even a day at the laundry. The ropes vaguely resemble sheets that would have been twisted tightly and attached together. The women are depicted almost naked, only covered with white-dotted black panties, and on their haunches, battling with the ropes, which seem to have some energy of their own.

The symbolism goes deep: Could the ropes be serpents? Cords of attachment? Neural pathways? Bits of DNA? Intestines? The women’s hair — usually painted vividly in deep dark black in most of Kahraman’s previous paintings, are here covered in cloth made of the same light pink material… The piece is titled “Entanglements with Torshi”. On the opposite side of the room, glass jars are aligned on three different raw of shelves, containing pickled vegetables — torshi, in Iranian-Iraqi cuisine – of the same, only brighter, mauve color.

With these elements, Hay Kahraman said she wanted to experiment on the relations between our bodies and “otherness.” This exploration takes the form of a depiction of female bodies interacting with micro-organisms. Whether vital bacteria travelling through the bodies, or hormones, for the artist they represent the “colonist” nature of microbiotic life, its foreignness to the human body yet its vital necessity. This allowed her to compare viruses and other bacteria inside of us to the refugees, outcasts and other foreigners in our societies: too often labelled as parasites, aren’t they on the contrary vital to human survival?

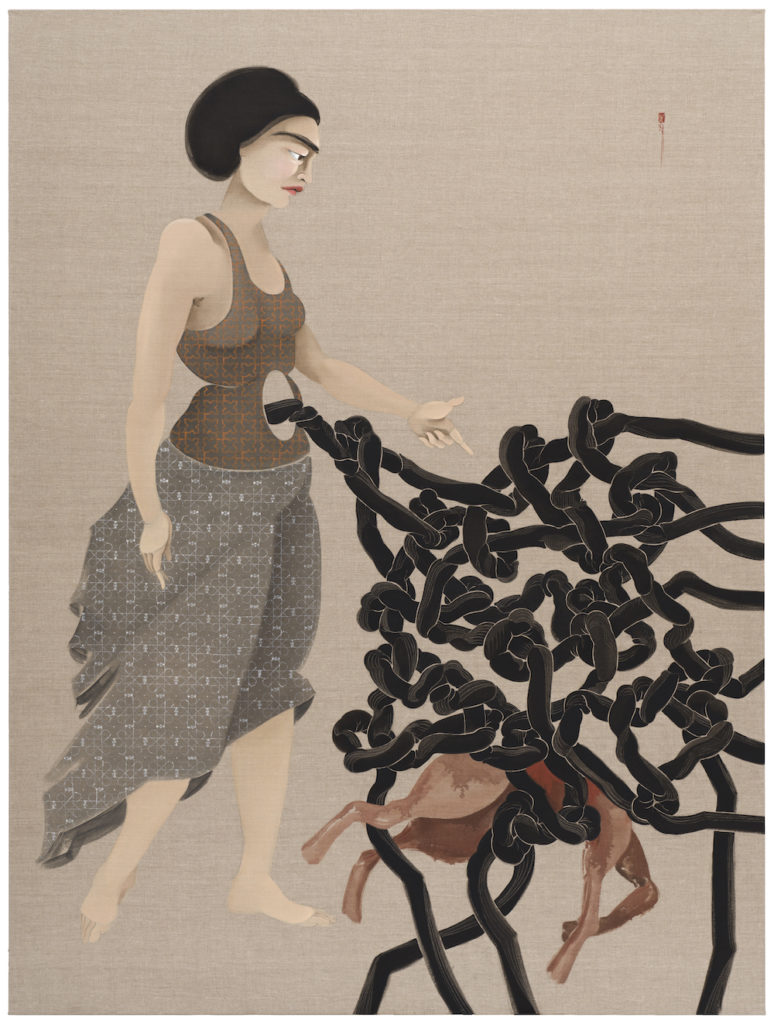

In the second room, the paintings represent similar women but surrounded by black ropes, resembling chains. Most of the women have their hair uncovered this time, black but tightened up. In one solo portrait, the lady is dressed, and the ropes are entering her belly via a large circled hole; she seems to be guiding the ropes, even more entangled that in the previous room. In a series of three paintings, women deal with a similar rope entering their body through their mouth. In the most striking painting, a woman is crouched again, and pours some of the mauve liquid over her head while surrounded by the black entangled knots of the rope.

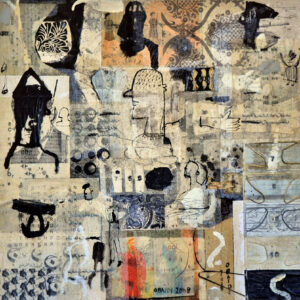

For the artist, these black knots represent the beliefs forcedly fed to people through civilization. Titled “NeuroBust” — a reference to the expression “myth busting” —one of the series tries to represent the “colonial ways of thinking” that have haunted the Middle East for decades. “Play Dead” alludes to the induced trauma linked to confinement, Kahraman explained. A few more elements are exhibited, with notes and sketches from the artist, showing the process behind this project.

The final room, downstairs, exhibits the resolving pieces. Painted on flax fibers, created after the artist conducted some research on bacteria and microbiome, they display her efforts to “learn from the microbes.” She again reflects on the Western popular culture that sees bacteria and microbes as dirty, foreign, invasive, if not hostile, while biology actually proves that they are key elements of survival and life. Two of the women here appear to be weaving their own hair into a black entangled rope, becoming a giant knot, from which it is multiplying itself into threads, almost like a spider’s web. Another female figure does the weaving from a rope exiting her pierced belly.

Hayv Kahraman described this process as a metaphor for dealing with different kinds of trauma. She also wanted to decry the process in which, western humanitarian organizations are using refugees’ experiences of trauma in order to “compile” them as “portfolios to build their case,” to file for asylum. “The system (humanitarian, governmental and social welfare agencies) requires the display of pain,” she writes. “The more you are known to have suffered, the higher the reward, creating a pernicious wound economy that keeps the refugees feeling stuck.”

Her paintings have often been filled with Islamic geometric patterns, but also stylistic references to Japanese and Arabic calligraphy, art nouveau, Persian miniature and Greek iconography.

The body, and especially the female body, is at the heart of her more recent exploration of the aforementioned themes, digging into research around trans-generational trauma and post-colonial affects. The body is for her both an object and subject to embody the artist herself as much as a collective.

I first saw Kahraman’s work in an itinerant show, “Still I Rise,” at Arnolfini in Bristol, in October 2019.

Her painting “The Kawliya Dance” represented women from a Roma heritage in Iraq, who were swept away in a dancing ritual. The ritualistic moves, in their traditions, are supposed to wash away the pain and discrimination that their community has been fighting for decades, if not centuries. The beauty of the painting on wood, the liveliness of the movements, the symbolic power of female hair in these painting were as evocative as the bodies and their microbes in these new ones, expressive and liberating for both the depicted women and the beholder.

“Gut Feelings” takes her approach to the next level, with even greater historical and political significance — and relatability — in a world with millions of refugees. The artist’s next exploration, “The Touch of Otherness,” will be exhibited at The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), Savannah (2022) and ICA San Francisco, San Francisco (2023).