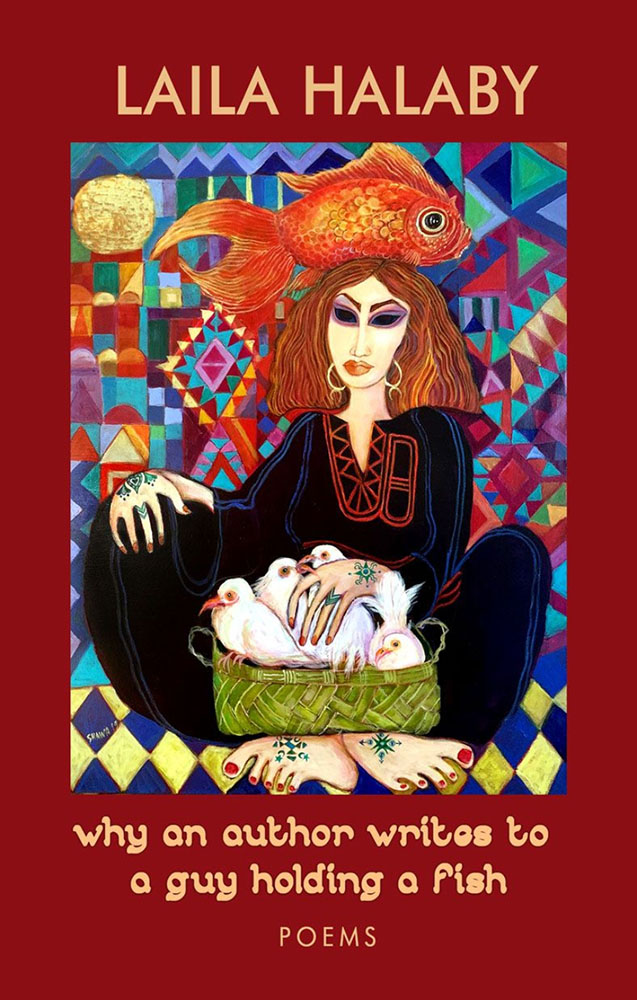

Why an Author Writes to a Guy Holding a Fish, Laila Halaby

2Leaf Press, 2022

ISBN 9781737446538

Eman Quotah

At my college, one creative writing professor challenged students to write happy love poems, an assignment everyone griped about. Apparently, writing about good love, love that goes well and ends well, doesn’t come easy for most poets.

Unlucky-at-love-and-dating tales, on the other hand, are part of the fabric of modern U.S. culture — the basis for many a book, short story, movie, TV show, song, blog post, memoir, essay, standup routine, poem, and tweet thread. The growth of online dating over the past few decades has only heightened both the comic and tragic potential of dating stories — or so I hear. I’m a serial monogamist who’s been married for more than 15 years. How would I have any idea?

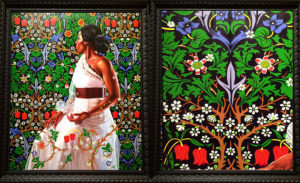

That’s the state of knowledge poet Laila Halaby found herself in more than a decade ago when her marriage of nearly 20 years ended. In her new poetry collection, Why an Author Writes to a Guy Holding a Fish, Halaby relates her experiences dating American men after being married to a fellow Arab. The result is a sort of rom-com in verse — though without a traditional happy ending — and the type of story an American woman of Arab heritage, such as Halaby, never (or rarely) gets to star in on page or screen.

At the start of the collection, when her husband leaves, Halaby is uprooted, like the twisted acacia tree in her front yard.

the night

before my husband moved out for good

he took some things

to his new apartment

while a fierce storm hurtled itself

through our neighborhood

violent winds

threw trash cans for blocks

ripped bushes out of the ground

knocked trees into houses

my older son looked out the window

sobbed at the sight of our crazy tree

lying stretched across the front path

as though it had gotten tired

of waiting for his father

Freed of the cultural expectations placed on her younger self — she never spells them out, but self-policed sexuality, limited dating, and marrying on the young side seem likely to me, a woman with an ethnic background similar to Halaby’s — and having escaped a loveless marriage, Halaby finds herself in a foreign land. In the title poem, she writes:

online dating

in America

in your forties

after a lifetime

of Middle Eastern sensibility

and almost 20 years of marriage

requires resolve

patience

and some cross-cultural understanding

Already someone who falls in love easily with people she meets, but never acted on it because she was a faithful wife, now she’s putting her picture online, meeting men in coffee shops and restaurants, and falling head over heels. Halaby encounters nice guys, racists, rich guys, and cheaters, and she begins to understand herself a little more. As a married woman, she’d “be smitten/fall into possibility … love was everywhere/except in my home.” But now that she’s divorced, Halaby starts to second guess her definition of love:

what if

all those years of wanting

unfulfillable longing

trying to do the right thing

translates

not

into love

but into a tsunami of something else?

This, perhaps, is the central question of the book. What does it mean to want love, to want to be loved? Of one lover, she writes:

on my right side

spanning from hip to breast

is the clear indentation

of your hand

that held me

caressed me

brought me out of an anguished stupor

I place my hand over yours

close my eyes

and squeeze

until the longing recedes

just a bit

Born in Lebanon to a Jordanian father and American mother, Halaby explained her identity this way in an interview with the American Writers Museum: “My father always lived in Jordan, my mother always lived in the States, so I’ve never felt like I’m Arab-American. I feel like I’m Arab and I feel like I’m American, but the hyphen is lost on me. Even though I feel like the hyphen is also where I live.”

In this collection, Halaby puts her Arabness on the page, but without the expected trappings of metaphorical language, food imagery, or very much transliterated Arabic. Arab is simply who she is. In “Other,” for example, Halaby explicitly links her experience of being racially othered in America to being lied to in love and unwittingly becoming the “other woman.”

lifetime

spent

checking that damn box

other race

other ethnicity

product of

the other

woman

fought

to be whole

complete

no marginal

shamefulness

only to become one

a lifetime

of resistance

leads to this?

other woman

will not do

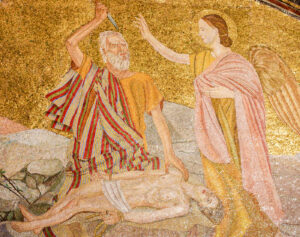

A comment on the ludicrousness of online dating and the weird ways potential lovers present themselves, the title Why an Author Writes to a Guy Holding a Fish also brings to mind the famous quote coined by Irina Dunn and popularized by Gloria Steinem: “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.” The guy holding the fish will, presumably, soon hold Halaby, and let her go. He’s the bicycle she wants to ride into the sunset, but instead, she’s left standing on her own two feet.

Why an Author Writes to a Guy Holding a Fish ends with an epilogue written in spring 2021, one more tale of dating gone wrong. First, there’s a potential setup by her physical therapist, with a great guy who happens to be a Trump supporter. Halaby declines, instead meeting up with a man she connects with on a dating app, someone she clicks with and who encourages her when she mentions, while they are “huddled together” on her computer, the poems about her breakup.

He ends up ghosting her. Of course. His silence becomes the impetus for her to move on and push forward.

I delete my profile

submit why an author writes to a guy holding a fish

change jobs

visit Houri

and write

another poem

and another

and another

It’s a meta satisfying ending to a writer’s story, one that suggests a new beginning, another work under way.

I bet it wasn’t easy to undress your pain, your unfulfilled dreams and desires – not to mention the daily struggles to make peace with a very complicated identity – before the eyes of the unknown. Writing these poems must’ve taken so much courage and a level of vulnerability that most of us are uncomfortable with, just like love itself. Thanks to the poet for writing and to the reviewer for reviewing.