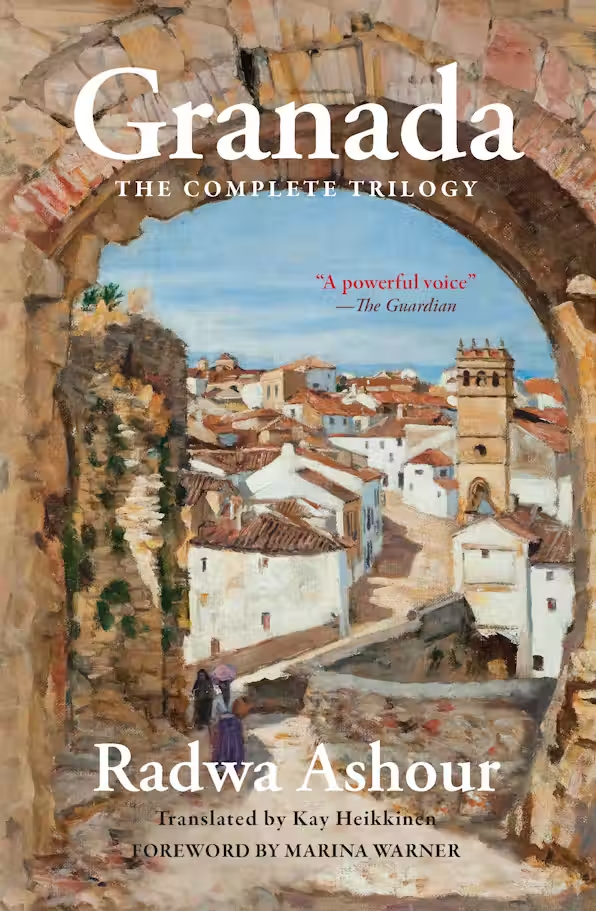

A trilogy of novels form an astonishing work of Arabic and world literature that covers 100 years, against the backdrop of 16th century Andalucia, and reverberates in the wars of conquest and occupation taking place today.

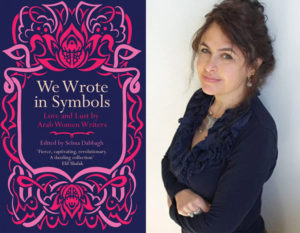

Granada: The Complete Trilogy by Radwa Ashour, translated by Kay Heikkinen

Hoopoe 2024

ISBN 9781649033765

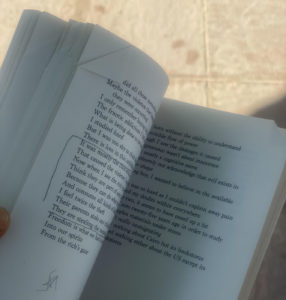

The arrival of Radwa Ashour’s complete Granada Trilogy (Thulathiyat Ghirnata, 1994–5), in a new English translation by Kay Heikkinen and on the 10th anniversary of Ashour’s death was a big moment. It was published during the ongoing Israeli genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, whereby a long arc completes a circle of horror with the participation of all major “western” powers, which is unfair to the trilogy and its author in some ways but urgently and overwhelmingly appropriate too. Ashour wrote of how images of the US-led bombing of Baghdad in 1991 gave her the image of naked helplessness that Granada begins with. It’s an image of catastrophe from which this trilogy unfolds with irresistible affect, imaginative precision and haunting import.

Hoopoe’s handsome edition comes with a useful introduction by Marina Warner, who refers to the book as “monumental” and a “magnum opus of prose fiction,” both terms that generated hesitance in me as I began to read. However, they suit what is the central and definitive achievement in Ashour’s striking body of work, which stretches across short stories, straight autobiography, novels including novel assemblages of fiction and memoir, three untranslated volumes of critical writing, and excellent translations of husband Mourid Barghouti’s poetry into English, not to mention a long career as Professor of English at Ain Shams University in Cairo.

If I restrict myself to only one essential accompaniment to Granada, it would have to be Ashour’s last novel The Woman from Tantoura, 2014 (al-Tanturiya, 2010), which shares the same translator and a comparable catastrophe in the ethnic cleansing and erasure of the village of Tantoura near Haifa in coastal Palestine by Zionist militia in 1948.

Fortunately, Ashour’s great novel is garlanded with others situated in regional cultures and historical contexts that necessarily engage catastrophes of finely drawn individual as well as collective kinds, but do so with ever-buoyant resistance. Those stories take place in and out of prisons, on islands, in Paris, throughout Palestine, often in Cairo, in Muslim and post-Muslim Granada, Andalusia, Valencia and Columbus’s so-called “New World.”

Ashour was unavoidably aware of the Nakba of 1948, the catastrophe deepening and widening in 1967, as well as the so-called Gulf War of 1991 when she was writing what became Granada, and yet her trilogy stands independent of all these events. They function as rich allusions and additions to Ashour’s sinewy fictive blend of archival acuity with what Warner describes as, “intimate, empathetic” witness.

The Fall of Granada

The trilogy is set in the middle of catastrophic events that bring to a conclusion in 1492 seven or eight hundred years of Muslim rule, cultural achievements and dissension, or commence the purgatory of a century-long ending populated by Moriscos (forced converts to Catholicism) that leads to a final expulsion in 1609. After torching Rondo and Málaga, huge well-equipped armies from Castile and Aragon in the north of the Iberian peninsula reach the last bastion of Granada’s independence, the Alhambra Palace, to formalize a treaty of surrender with a ruling elite of wazirs, generals and scholars representing Sultan Muhammad XII.

Granada opens with the sight of a mutely naked woman in the streets that bookseller Abu Jaafar reads as an omen before rumors of bodies seen in the town’s Genil River circulate after just one general refuses to sign the treaty of surrender and storms out of the palace. Visions and prophecies are countered by a flashback to the arrival of a newly orphaned boy named Naeem, whom Abu Jaafar has taken on as an apprentice in his business. Reality intervenes again when a body is retrieved from the river: “The eddies of the river had swallowed up what hope remained, the community had been scattered, and the people had been orphaned.”

Ashour has dropped us right into the middle of turmoil, agitated insecurity and eddying stories in her characteristic way, without official or authorial narrative frameworks. Instead there are stories within stories drawn along by people to people entanglements. With the arrival of another orphan Saad, from a family of Malagan silk-weavers, Ashour offers a typical response to impending erasure:

He became convinced that nothing was ever lost, and that the human mind was a marvelous box … preserving incalculable, innumerable things: the smell of the sea; his mother’s face; faint yellow rays piercing green vine leaves, wet with raindrops; threads of silk on his father’s loom; his grandfather’s cough in the morning; the laughter of the little girl; the taste of a green almond; a broken jar from which oil flowed; a bead detached from the string of prayer beads, rolling toward him in his hiding place behind the cupboard.

This long quotation exemplifies the undeclared foci of Ashour’s work and this novel in its resoluteness; the scribe or copier’s “radical conservation” as she called it in her essay, “Eyewitness, Scribe, Storyteller” — that was published in 2000. The scrappy smallness of its detail; the preserving and passing-on under impossible circumstances relates to what philosopher Emanuele Coccia describes in The Life of Plants A Metaphysics of Mixture as a “point of life.” That is, “the world is the breath of the living. All cosmic [meaning planetary] knowledge is nothing but a point of life [vie] (and not just a point of view [vue])” with its false god’s eye perspective on things.

Coccia is writing about plant life here as well as Life as such, but this is a useful way to think through Ashour’s ability to engage histories freed of obsolete framings by the merging of essential qualities of life bit by bit in compelling networks of human stories from below and specifically from below surfaces that include the ground. Stylistically this is the “interplay” of dark and light that she attributes to the arabesque (Ashour, 2000), but it embodies more than style.

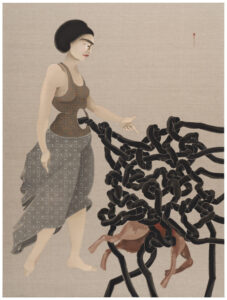

Meanwhile, as the deadline to comply with those that Ashour only ever calls “the Castilians” looms, the people of Granada “watched the mass emigration of the nobles, the prominent, and the rich. It was a tumult, a fevered face of buying and selling … swords inherited from grandfathers and grandfathers’ grandfathers.” They watch Christopher Columbus’ triumphal parade through the city squares, stirring “enthusiasm and fear of that new, unknown world discovered by the man riding on his horse.” Glass cases of gold dust and ingots are followed by “the captives … people who live in the new world!” who walk “with deliberate steps, their hands tied” retaining “the elegance of their stature” and “colored feathers fixed in bands around their heads.”

The Age of Modernity has commenced!

After the elites flee, Abu Jaafar introduces his world to us by setting out through the gates, down to the river, paying attention to the fortresses and palaces, “cypresses, palms, and stone pines” on one side of the river, “figs, olives, pomegranates, walnuts and chestnuts” on the other, noting the buyers and sellers, the perfumers, potters, glassmakers, brass merchants, and goldsmiths, entering the cloth bazaar to contemplate the linens, wools and silks, and finally making his ablutions to pray in the Grand Mosque before returning “to the papermakers quarter where his shop was.”

We meet Abu Jaafar’s family, generations of which animate the coming century and hundreds of pages, most notably his daughter and spiritual heiress Salima, the principle character of the first part of the trilogy, in whom Abu Jaafar and Radwa Ashour place their hopes. In childhood Salima queries Columbus’s recent discovery, saying it is not a “new” but “different world.” Ashour continued, “When she wanted something, she kept on asking for it and insisting, never flagging or tiring, and she did not give up or allow anyone to stop her until she got it.” Abu Jaafar lives for Salima’s mind; “a mill that never ceased turning, observing, contemplating, questioning and becoming absorbed in thought” and begs his son Hasan to become “a great writer like Ibn al-Khatib, so they will record your name together with Granada’s in every book.”

Cardinal Jimenez arrives to tighten the occupier’s grip in 1499, staging the conversion of Hamid al-Thaghri — rebel of Rondo and Málaga — in “the mosque of Albaicin, now named the Church of San Salvador.” Thaghri’s mortified followers “had built a small, warm room for him in their hearts … which he filled with his heroic feats and his justice.” The Castilians begin raiding books from mosques and schools, “the Alhambra and Jewish Granada,” gathering them in carts from all quarters. Abu Jaafar and other booksellers respond by securing their books in “a number of places; mountain caves, the ruins of abandoned houses, and basements of homes,” but the Castilians burn many more cartloads in the main square at unbearable cost.

Record what?

In Ashour’s excellent and often quoted essay subtitled, “My Experience as a Novelist,” her credo is contained in the main title: “Eyewitness, Scribe and Storyteller.” This references an obsession to record “as the ancestors did. Record what? A geographical space dense with a resonant history, a composite of past and present, overlapping territories constitutive of an emotional and moral space for self-awareness and self-definition.” She identifies this as a generational trait in response to 1967; when her generation was “denied and disfigured,” making their writing “a retrieval of a human will negated.” The town of Granada has a particular resonance in Arabic and Palestinian literature — think of Darwish’s “Andalusia of the possible” — but for Ashour it provided, as she writes in her essay, “a means to explore my fears, impotence and also the chances of survival through resistance.”

In Granada, both of Abu Jaafar’s children marry. Salima marries Saad and they become distant as she buries herself in books and he leaves to join the rebels in the mountains. Hasan, her pragmatic brother, marries Maryama, daughter of a “praise singer.” While Maryama develops a reputation for acts of cunning defiance, Salima has larger if equally constrained visions:

She was stifling in the prison of a vile time when acquiring books was a crime subject to punishment… she waited until night descended and the household went to bed, then she lit the lamp and read and her prison grew larger, expanding gradually until the bars disappeared in the light of the sun that shone from the book and from her intellect.

This is a prison of time itself, she says cannily but “bitterly, staring into an ancient time that took its children by the hand to large libraries, to the patronage of a wise ruler, to travel that could satisfy the heart’s longing for the scholars of Egypt and Syria.” She returns most often to Avicenna’s The Canon of Medicine amongst her ten meager books and searches for more. In these ways, “she heeds the vile age… and then she does not.”

Critic Eric Calderwood in On Earth or in Poems, the Many Lives of al-Andalus explores the import of Salima’s bookishness, expanding on Ashour’s notion of “radical conservation” to excellent effect. He reminds us that “as a model for Salima’s education, Abu Jaafar looks to the example of Aisha bint Ahmad, one of the illustrious adības of al-Andalus. Salima thus emerges as a figure of ‘radical conservation,’” an homage to these historic “foremothers” and a continuity rather than a “rupture from tradition.”

This expands the significance of Ashour naming Saad and Salima’s daughter Aisha — the product of a fleeting return from Saad’s rebel base — in the early 16th century. Hassan records his niece’s birth officially with a Castilian name; “Esperanza (hope). Sometimes he would call her Aisha, sometimes Esperanza, and Amal (hope, in Arabic) a thousand times.” Meanwhile the Castilians renew demands to convert or depart. Maryama persuades the family with her stark refusal to leave, even at the cost of “an entire life whose vocabulary had become accusations and sins!”

The Prison of Time

Saad is caught, tortured and imprisoned for three years, during which “desolation … you see your loved ones more, because there is plenty of time, and because they come to you out of concern for you in your trial and allow you to contemplate their faces as long as you like.”

In “On Sticks, Straws, and Lanterns: Reading Radwa Ashour in an Egyptian Prison,’’ former Egyptian political prisoner Abdelrahman ElGendy wrote of how valuable Ashour’s insights about prison time were to him inside Egypt’s notorious Tora Maximum Security Prison. “Her words shaped — even saved — my life in prison,’ he wrote, specifying her essays and The Woman from Tantoura, which transported him to its “core” beyond mere historical recovery; “its scents, tastes, the distinct feel of its dust kissing one’s bare feet.”

ElGendy continued: “Radwa’s work prompted me to question: Where do untold stories go? If they never find an ear, do they cease to exist?” This prompted his own writing against the “radical hopelessness” he felt, the acceptance of which was also liberating. He cites Ashour again, from her late as-yet-untranslated memoir Athqal Min Radwa (2013), written during the January 2011 revolution while battling cancer: “There’s always a chance to crown our efforts with an outcome other than defeat, so long as we resolve not to die before we’ve sought to live.” Untold or unrehearsed stories reside in boxes within boxes invoked as tools of “radical conservation.” Granada’s Saad bears prison time, as Ashour wrote, “because that amazing box in his head was able to give him jewels that glittered and shone in the darkness of the prison.”

In Granada it is now 1527 and Saad has been released only to discover that Salima has been taken in by the Inquisition on charges relating to “black magic.” We know the date because it is on the judgment pronouncing her guilt, after proceedings that Salima regards as “an absurd game run by eccentric idiots.” Punishment is death by fire, which is scheduled for the same square that Granada’s books were burned in earlier.

The first part of the trilogy ends here, with Aisha being told a familiar story by Maryama about a tree in heaven that harbors as many green leaves as “people on the earth.” It is “a large tree, Aisha, and leaves fall from it and other leaves grow, without stopping.”

Return. Depart. Remain.

The remaining shorter books of the trilogy, Maryama and The Departure, center on Maryama and nephew Ali, the son of Aisha and Maryama’s son Hisham. Granada has become a saga of “errancy,” in Saidiya Hartman’s usage: “the social poiesis that sustains the dispossessed” in their search for ‘‘a place better than here’’ while “inhabit[ing] the world in ways inimical to those deemed proper and respectable.” It turns out that the “village Sheikh” of al-Jaarfariya knew other members of Ali’s family, who first fled to the village and then to Fez, and offers sanctuary to Ali too. “Then the days passed and one morning he noticed that though he was ‘the stranger’ he was no longer strange. He had begun to cultivate the earth, waiting for the season of olives to pay his debts, buy his clothes, and make sure of his provisions.”

I can only imagine reading this thirty years ago and now recall the ways in which Ashour has written about closed regimes of literal prisons and non-literal imprisonment in Blue Lorries (Faraj, 2008), from which the protagonist Nada emerges hurt but defiant, strong and uncowed, having “sought to live.” Ashour is unerringly good inside these minds and those like Ruqayya’s, the central character in The Woman from Tantoura, facing dispossession, displacement, and death from every direction in the early days turning to years of the Nakba, and yet always making the same gamble on living. Ashour’s work embodies this refusal to abandon, this same story within a story to be radically conserved in a chest within a chest for future planting in freshened earth.

Chaotic and/or Composite Terrain

Radwa Ashour has written of being “born in Manila el-Rawdah, an elongated stretch of land which knits the two sides of the river in Cairo” with views of Pharaonic pyramids, Byzantine, Islamic and Coptic monuments and of dwelling in multiple languages. At the southern tip of the island stands “one of the oldest Islamic monuments in Egypt” the “Nilometre” or “al-Mequiass,” vital for land irrigation. Thus, “to tell my story was to include that composite experience which constantly incorporated the old in the new.” Or, once again, “a composite of past and present, overlapping territories constitutive of an emotional and moral space for self-awareness and self-definition.” The way in which these composite elements subvert all boundaries is also a description of Ashour’s work as crystallized so powerfully in Granada.

There may be a further dimension to this in Michel Serres’ figure of the harpedonaptai, “whose role was to venture with their measuring rope onto the muddy floodplains of the Nile, after seasonal floodwaters had abated,” as I wrote in a previous essay. Serres grew up on the Garonne river outside Bordeaux, working on his father’s dredger against the regular flooding there. He continued in The Natural Contract, “Since the flood erased the limits and markers of tillable fields, properties disappeared at the same time. Returning to the now chaotic terrain, the harpedonaptai redistribute them and thus give new birth to law.”

If we assemble “radical conservation,” creative resistance, “social poeisis,” and muddy redistribution together, we can imagine routes, even horizons, beyond the endgames of Modernity in climatic breakdown and genocidal horror. Granada is primarily an astonishing work of Arabic and world literature, but in the nowness of a translation for the 2020s, it’s also a marker of the catastrophic moment from which all our presents emerge. Read it to enjoy Ashour’s brilliant conjuring of points of life at Granada’s height and precipitous fall, but also as a resource for what is to come if, as she said before her own death, “we resolve not to die before we’ve sought to live.”

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)