A crucial, earlier period of Bell’s life, between the years 1889 and 1914, during which she traveled Ottoman-era Anatolia far and wide over the course of 11 different visits, has been largely absent from many accounts. It now, however, takes center stage in a new book by Pat Yale.

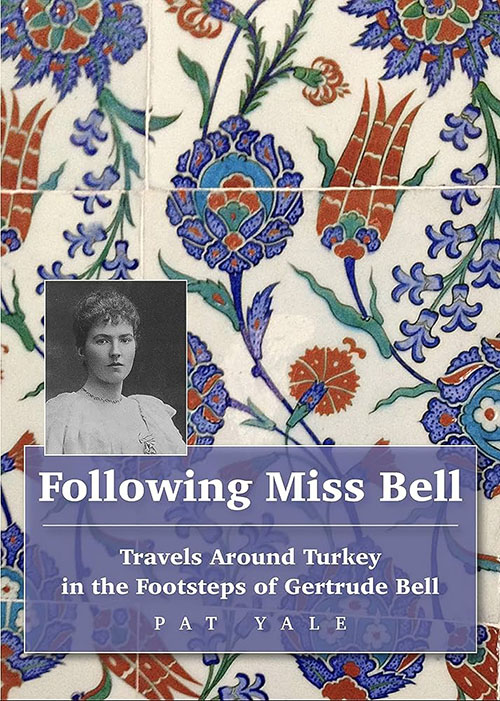

Following Miss Bell: Travels around Turkey in the Footsteps of Gertrude Bell, by Pat Yale

Trailblazer 2023

ISBN 9780300251289

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The grand story of archaeology in the Middle East has long been one told exclusively through European eyes. But beneath those early 20th century tales of fantastical adventure, ancient curses, spies, gravediggers and kingmakers, was a colonial project that helped shape the fractured present of the region. Archaeologists went to the Near East in search of historical evidence that would help lay claim to the primacy of a universal, Western civilization, and brought back to Europe not only plundered artifacts, but a vast knowledge of the landscapes, geography, peoples and internal political dynamics of the region. Thus, the archeological trenches, with the mass plunder of antiquities, asymmetrical power relations with local stakeholders, and support for nascent nationalisms, also helped dig the trenches of wars that ultimately redrew the map of the entire Near East.

Today, the names of certain archeologists, such as Alfred Layard and Leonard Woolley in Iraq, Howard Carter in Egypt, the infamous Lawrence of Arabia or even Ottoman statesman Osman Hamdi Bey, are notorious for the roles they also played as spies for hire, political officers, and important decision makers. But one name, equally important to this story of both mapping and plunder, discovery and war, remains less prominent. It is that of English writer, archaeologist, and political officer Gertrude Bell (1868-1926).

Bell spent most of her life exploring and mapping the region, becoming highly influential in helping shape British imperial policy on Iraq and playing adviser to both the High Commissioner for Mesopotamia, Percy Cox, and the newly minted King Faisal. From 1914 onwards, the British War Office relied on her assessments, and she was instrumental in the creation of the British-backed Kingdom of Iraq in 1921. Her political role in Iraq as well as subsequent appointment as director of antiquities are well chronicled. Yet a crucial, earlier period of Bell’s life, between the years 1889 and 1914, during which she traveled Ottoman-era Anatolia far and wide over the course of 11 different visits, has been largely absent from many accounts. It now, however, takes center stage in a new book by Pat Yale, Following Miss Bell: Travels around Turkey in the Footsteps of Gertrude Bell (2023).

Like Bell, Yale hails from England, and, like Bell, she is particularly knowledgeable about Turkey, where she has lived and worked as a travel writer since the 1990s. Yale not only relays how the 20-year old Bell, armed only with Murray’s 1853 guidebook, set out from Constantinople in 1889 on a journey that would go on to transform the borders of the Middle East — she undertakes the same voyage herself.

The preparations for Yale’s travels in Bell’s footsteps began almost incidentally. While attending a 2014 exhibition of the guestbook of Nazlı Hamdi, the daughter of Ottoman statesman, intellectual, archaeologist and painter Osman Hamdi Bey, Yale came across an autograph of the “desert queen” Gertrude Bell. Her curiosity ignited when she read the quote Bell had chosen by the 10th century Arab poet Al Mutanabbi: “The most exalted seat in the world is the saddle of a swift horse and the best companion of all time is a book.”

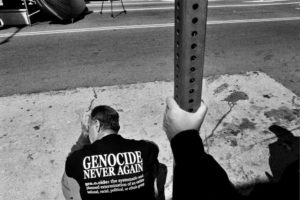

Yale immersed herself into archival research based on Bell’s extensive correspondence and diaries, and read different accounts of Bell’s adventures in the Near East as the Oxford-educated daughter of a wealthy industrialist, from her encounter with Fattuh in Tarsus (an Armenian she hired as a servant to accompany her as she crossed Anatolia from the Aegean to Mesopotamia) to her chronicles of the displacement and massacres of Armenians after the Adana pogroms in 1909. Yale also examined Bell’s photographs, in which the explorer immortalized Byzantine ruins that have since become inaccessible or lost to time, and the research notes scattered in her diaries that would become her scholarly work on Cilicia and Lycaonia. Curious about how much had changed or stayed the same in the places that Bell visited, Yale boarded a bus in Izmir with the intention of retracing all of Bell’s journeys through modern Turkey.

The result is a book like no other, juxtaposing two different timelines and two separate worlds: Bell’s Ottoman Anatolia, populated with American missionaries, Armenian priests, European diplomats, Francophone Greeks, and Levantine mansions, and Yale’s present-day Turkey, reshaped by nationalism and bouts of political instability.

Bell undertook her voyage with an entire Victorian entourage, a caravan of horses loaded with servants, books, food supplies, and muslin gowns. The journeys were often incredibly challenging and logistically costly and risky, requiring long horseback rides, the crossing of muddy rivers, negotiations with local chieftains, and extensive planning. Writing near the end of the Ottoman Empire as a second-hand witness of the Armenian Genocide, and direct observer —and deviser —of the eventual collapse of Mehmed VI’s realm, Bell is also chronicling a period of assassinations, coups, historical transitions and crises.

But the picture Yale paints of modern-day Turkey is no less tumultuous or vibrant. Her solo travels — exchanging horses and caravans for buses and minivans — give her a more intimate vantage point, and permit her to speak more directly with locals, who are largely absent from European narratives of the past. Her challenges, however, are no less daunting than Bell’s; her travels coincide with political instability following an election, and the restive situation in the southeast results in the assassination of human rights lawyer Tahir Elçi in front of the Dört Ayaklı minaret, only seven weeks after Yale passes in front of it. Furthermore, she faces difficulties attempting to identify the sites Bell visited, following the waves of name changes meant to establish a firmer Turkish identity for various locales. She arrives at many sites to find them poorly preserved, or to find some bustling locations transformed into parking lots or shuttered buildings, or having all but entirely disappeared. By contrast, others, such as the Hellenistic and Roman sites of Ephesus, Aphrodisias, and Laodikeia, have been re-excavated and restored, and have since become some of the most popular and magnificent archeological sites in modern Turkey.

At the beginning of Bell’s adventures in Anatolia, we learn a great deal about archaeology — from well-known places such as Miletus, Sagalassos, or Bergama, revisited by Yale, but also about lesser-known places I had never heard about, such as Blaundos or Larissa. Yet it is actually in Bell’s Smyrna that we learn about something completely erased from the social memory of Turkey: the everyday life of Levantine Izmir with its palatial homes and multilingual populations. Their erasure becomes even more accentuated by Yale’s visit and conversations with a few singular characters from the vanishing community, clinging fiercely to this interrupted past, but keenly aware that there might not be another chapter.

When Yale tries to find the Van Lennep family estate near Bornova (Levantines of Dutch origin where Bell stayed on several occasions), she finds that it has been overtaken by floodwater resulting from the completion of the Tahtalı Dam in 1998. Only a half-submerged minaret is left to mark the area.

In Harput, Central Anatolia, when Yale inquires about the famous Euphrates College founded in 1852, she learns that the last remaining part burned down 20 years ago. Traces of the Armenian genocide in the region remain, most accurately preserved in absence. While searching for the monastery of St. Basil, but finding only a few foundation stones, Bell stayed as a guest in 1909 at Talas College, whose students were predominantly Armenian, and a priest returned from Adana bearing details of the recent pogrom there. Soon afterward, the college was abandoned and decades later transferred to local authorities. Before boarding a minibus to Elaziğ on her own journey to Talas village, Yale recalls photographs from 1915 that show Armenian men being herded to their deaths. “A silence falls,” she writes. “It’s a silence weighted with the knowledge of death.” In Central Anatolia, she encounters the double silence of displacement that came first with the extermination of Armenians in 1915 and then later with the expulsion of Greeks during the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Through Yale’s skillful storytelling, and its complex intertwined narratives between past and present, we come to witness the steep decline of rural Anatolia today, rapidly depopulating as the young generation migrates elsewhere in search of new opportunities. A truly disheartening picture of the status of religious minorities appears, particularly in the eastern frontier, where tiny communities are squeezed between political conflict, immigration and officially sanctioned sectarianism. The Greek community has vanished, and the few Armenians who remain have survived only by sheer miracle. We also learn of the once thriving Syriac community in Mardin, who are today struggling to hold on to their ancestral land. The image exists in sharp contrast to Bell’s accounts of missionaries, schools, villas, affluent towns, festivals, churches, and near unlimited cultural heritage.

Yale gives crucial space for Turkish people to narrate their own stories, engaging in dialogue with the people she encounters on her way, from drivers in distant locations, to archaeologists, heads of local government, tourist guides, and local townspeople. She allows them to explain how they relate to many of these ancient sites and ruins, whether through family memories, or displacement or reinterpretation. This serves not only to show how enshrined these historical and archeological sites are in the collective memory of the local community, but to underline their importance in people’s day-to-day realities. It also defies current writings about culturally rich archaeological sites, whereby the lives of the modern communities surrounding them are regarded as secondary or unimportant. While Yale’s counternarrative approach might well be unintentional, it nevertheless enriches the archaeological material.

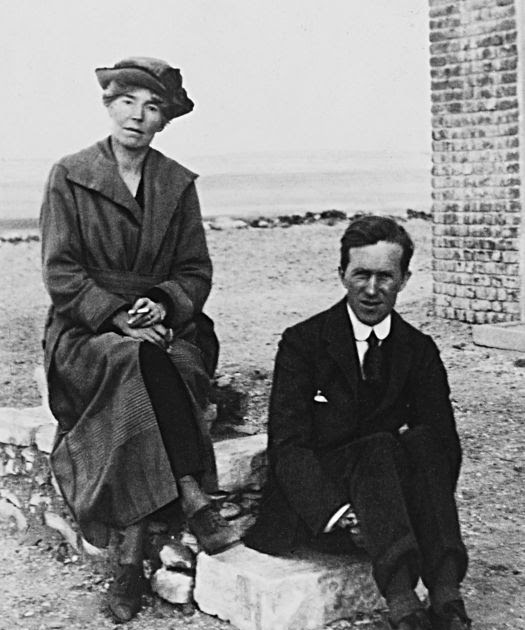

While Turkey isn’t the place most strongly associated with Gertrude Bell, and while she never put together all the threads connecting her to Anatolia in a single book, the country must have left a lasting impression before her premature farewell in 1914. It was there, after all, that she met some of the most important men in her life. An excavation at Binbirkilise introduced her to the married British military officer Charles Doughty-Wylie, who would become her lover (he was subsequently killed on the battlefield in Gallipoli in 1915). In Carchemish she met both archaeologist Leonard Woolley, who under her tenure would begin conducting excavations of the city of Ur in Iraq, and the young “Ned” Lawrence, who would go on to become Lawrence of Arabia and whose legacy has overshadowed hers. And in Constantinople, she met Colonel Mark Sykes, one of the masterminds of the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

And as if in testament to Bell’s lasting influence, Yale indeed finds a number of people in Anatolia who remember her, such as Hamza Kaya in the village of Dara, whose great-grandfather guided Bell and a Syriac priest from Washington at Mor Augen. She even comes across a curious memorial of Bell in a tea garden in Dinar, at the source of the Meander River. But the most striking encounter is one with a priest at Mor Yakup monastery in Nusaybin, who posed the most difficult question of all: Why did Yale think that Gertrude Bell killed herself?

No answer to this question is given, as no one answer is possible, but Yale does attempt to grapple with the complicated intricacies of Bell’s life beyond the wealth and success that she appeared to have enjoyed. Archaeologist Eleanor Scott notes that the difficulty of being a woman in Victorian England was such that it would in fact have been easier for Bell to be a woman amongst the sheikhs of Arabia. She reminds us, too, that although Bell was one of few women accepted to the Society of Antiquaries in London, there’s no record that she ever set foot in it. Additionally, in her private life, Bell experienced much disappointment, not only in ill-fated romantic affairs that came to nothing, but also by living long enough to witness the slow decline of her influence.

Yale lets us know of Bell’s tragic demise early on, which tinges the entire narrative with a sense of inevitable melancholy. Writing from the restaurant of the Orient Express, the same train service on which Bell arrived to Constantinople in 1892, Yale reflects on the end of Bell’s life: “I’m painfully conscious that I’m about to set off to retrace the footsteps of a woman whose life almost certainly ended in lonely Baghdad suicide.”

The tragedy of Bell’s legacy is of course larger than that of her own life. Her reputation in Iraq, which is not the topic of Following Miss Bell, remains contested, and the lines she designated in the sand as its borders, as journalist James Buchanan put it in the aftermath of the US invasion in 2003, have done less than well. Bell was torn between her loyalty to British imperialism and her love for Iraq, and the inheritance of her sectarian vision is a state of permanent conflict. As an archaeologist who passed laws against antiquities trafficking in 1924, how would Miss Bell have reacted to the looting of 15,000 artifacts from the Iraq Museum that she founded, in the chaotic aftermath of the American invasion? What would she make of the Iraq of today? Would she recognize the role she played, and played by others like her, in its destruction?

Yale’s book doesn’t grapple directly with these questions, but it does provide a glimpse of Bell’s early days as an explorer, and recounts the journey that would turn her into that ambitious political player who became an adviser to kings.

The history of modern archaeology, as Gertrude Bell knows, is also a history of destruction in the name of preservation and progress, but it is also a history of transformations, acculturation, oblivion, and constant change. Many places in Anatolia have changed significantly even since Yale began her own travels for the purposes of the book in 2015. The Hagia Sophia was transformed back into a mosque in 2020, and that same year, the old town of Hasankeyf was submerged under the waters of the Tigris River, which burst through the constraints of the Ilısu Dam. The 13th century caravanserai at Sultanhanı in Aksaray, where Yale concludes Bell’s journeys, has since been opened to the public as a market and hosted a contemporary art exhibition when I last visited in 2022.

But most shockingly, the old city of Antakya, where Bell recognized the beauty of the timeless heritage of Antioch, has vanished completely after the massive earthquakes that rocked the region in February 2023. Today it is a pile of rubble, abandoned to its fate.

The larger-than-life ruin of present-day Antakya underscores the importance of preservation, even of simple images of a place as it was once — a hundred years ago, or five years ago, seen through the eyes of these curious travelers, giving us a glimpse into a past now completely lost. Following Miss Bell makes clear that both Gertrude Bell and Pat Yale share a passion not only for the region, but for its peoples and their stories, and have been witnesses to its tragedies as well, even if their travels were separated by a century. In one passage, Yale, recounting Bell’s descent to the seaside village of Çevlik near Antakya in 1905 — then an Armenian village and now populated by Alawites — to visit the Hellenistic city of Seleucia Pieria and the Vespasian Tunnels (still intact today), shines forth with such mesmerizing candor that makes it seem as if Gertrude Bell and Pat Yale have now become one and the same voice: “With the sun shining down on it, Gertrude saw in Çevlik the beauty of the Bay of Naples, the steep sides of Kel Dağı (the ancient Mt Caussius), playing understudy to Vesuvius. From the beach she gazed out to sea and allowed herself to fantasize that she was camping near the spot where her hero, the great Seleucus, had been laid to rest. Ahead of her rose a hall of columns carved from rock. It was ‘fragrant of the sea and fresh with the salt winds that blew through it: a very temple of nymphs and tritons.’ Beneath the sultry sky of an overcast morning such thoughts seem almost willfully whimsical.”

Following Miss Bell: Travels Around Turkey in the Footsteps of Gertrude Bell by Pat Yale, is published by Trailblazer. It is available in Turkey from Pandora and Homer. It will be released in the UK in September and internationally in February 2024.

I can’t wait to receive my copy of the book, which has been on order from Waterstones for a while now. My appetite has been truly whetted to learn about Gertrude after she escaped the gentility of her home in Redcar, and embraced Turkey and Iraq.