Maalouf draws a line from pivotal years in Middle Eastern history to some of the most pressing dilemmas currently facing humanity.

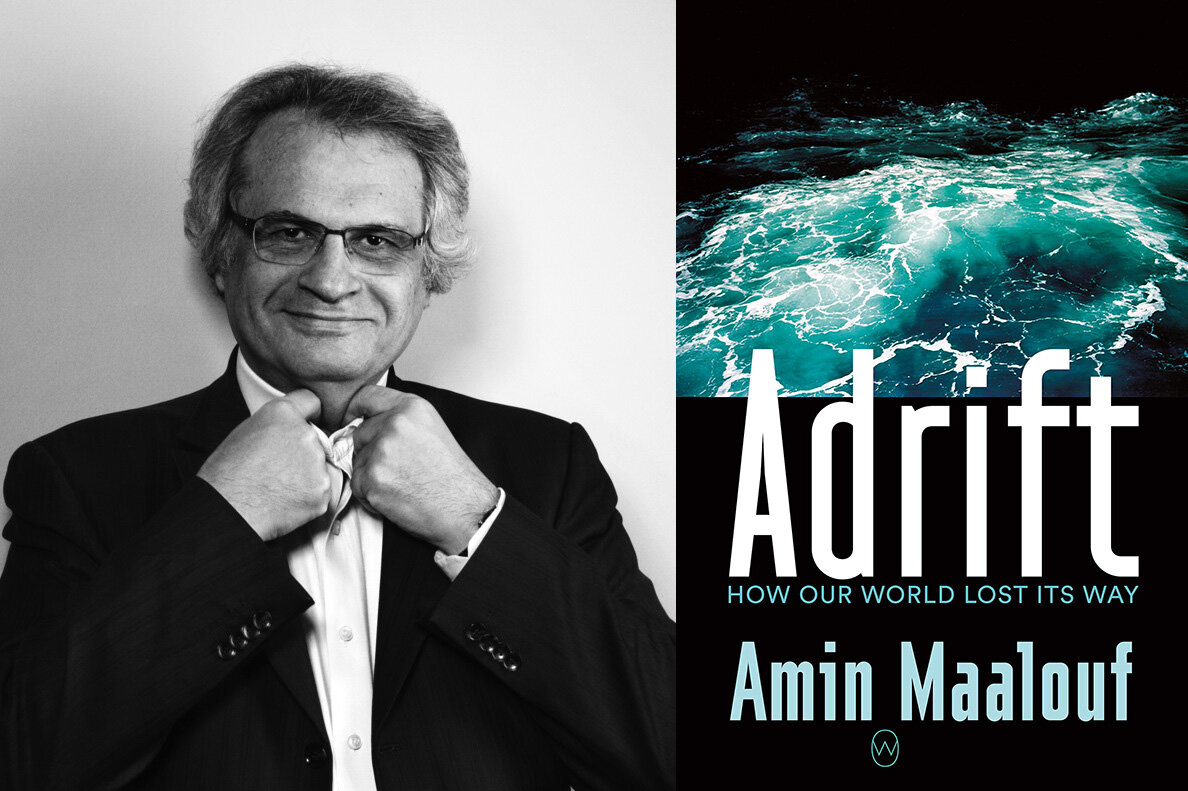

Adrift: How Our World Lost Its Way by Amin Maalouf

World Editions (2020)

ISBN 9781642860757

On Aug. 4, two explosions rocked the port of Beirut, causing hundreds of fatalities, leaving thousands homeless, resulting in unprecedented damage to the Lebanese capital and further compounding a volatile situation already made unbearable by the twin woes of Covid-19 and a crippled economy. In the wake of the disaster, it was as though something had irrevocably shifted. Gone were the street parties and cheeky slogans of the October Revolution, the sanguine spirit of the protests that had moved me to poetry and brought us in the diaspora to the Lebanese embassies of our host countries in solidarity. Lebanon is bone-tired now, and she is livid. At Martyrs’ Square, activists have hung nooses destined for the politicians whose corruption and negligence they blame for the tragedy. How far back in history would we have to go to pinpoint the root of the problem? This latest catastrophe seemed to be only the culmination in a long series of misfortunes.

“I did not know the Levant in its heyday,” writes the 71-year-old Amin Maalouf, Beirut-born and winner of the prestigious Prix Goncourt for his 1993 novel The Rock of Tanios, which weaves personal and political, fact and fiction together in a tale of 19th century Lebanon. “I arrived too late, all that was left of the spectacle was a tattered backcloth, all that remained of the banquet were a few crumbs. But I always hoped that one day the party might start up again, I did not want to believe that fate had seen me born into a house already condemned to demolition.”

His words will be achingly familiar to generations of Middle Easterners who have had to endure hardships in their countries of origin or watch them unfold from afar, sighing for bygone times. I myself was raised starry-eyed on an idea of pre-Civil War Lebanon, as it was passed down to me by my mother and aunt, both in the diaspora, both wistful for a homeland or their childhood or both. I learned that my family had had an olive grove and an apple orchard; that, as kids, they would drink from crystal-clean brooks in the Kadisha Valley; that my grandfather would make regular trips to Tripoli and bring back sweets, their rosewater fragrance filling the house. They would try to recreate recipes in their new country, but the taste of parsley and zucchini was never quite the same. Lebanon became a paradise for me, and only the reality of its recent years — and an ill-timed visit during its 2016 trash crisis — would challenge this notion. And even then, I still loved it.

Amin Maalouf was born in Beirut to Christian parents from Melkite and Maronite backgrounds. He was the director of the Beirut-based daily newspaper An-Nahar until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1975, at which point he moved to Paris, where he’s lived for nearly 50 years. Although his first language is Arabic, Maalouf chose to write in French. He has won several awards and honorary degrees from universities worldwide. His work has been translated into over 40 languages. His nonfiction, most notably In the Name of Identity, Disordered World, and most recently Adrift, often explores themes related to the junction between East and West, identity, and what he deems the universalist values of tolerance and pluralism.

Maalouf spent his early years in Egypt. In Adrift he writes, “I am not trying to prove something,” summoning examples that testify to the cultural richness of an Egypt he fell in love with through his own family’s stories. “I am simply trying to convey the impression I got from my parents: that of an exceptional country experiencing a privileged moment in its history…Of course, a part of this was the commonplace nostalgia anyone in the twilight years of life might feel when recalling their gilded youth. But there was more to it than that; my mother’s word was not my only evidence. I have listened to so many people, read so many accounts that there is no doubt in my mind that — for one shining moment, for a particular section of the population — there was a paradise called Egypt.”

Nostalgia, however, that sentimentality that bathes the past in a soft glow, is too rosy a word to describe the quality that characterizes Adrift: How Our World Lost Its Way (first published in 2019 by Grasset as Le naufrage des civilisations and translated by Frank Wynne). The author grieves for a Levant lost to conflict and the many vicissitudes of a turbulent twentieth century. So significant was the turmoil that set the region on a “descent into hell” that Maalouf sees in it the origin seeds for the entire world’s malaise. He is not unjustified in his assessment of the gravity of those events, either.

Maalouf deftly draws a line from what he deems to be pivotal years in Middle Eastern history to some of the most pressing dilemmas currently facing humanity. From the humiliating Arab defeat in the June War in 1967 and the critical year of 1979 — which saw the Iranian Revolution, the Siege of Mecca, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan — to the conservative ‘revolutions’ of Reagan and Thatcher and the fall of communism, he pins cause to effect all the way down to the present year and its host of ills: the fragmentation of society, the threats to privacy in the name of security, and the damage wrought by unchecked capitalism, among other troubles. The scope is very large, indeed, and might have benefitted from a tighter focus to allow for room in exploring the details of major events that, individually, merit their own books. Maalouf has taken on an ambitious task in covering so much ground and tracing a general condition of the entire contemporary ‘world’ back to a multitude of decisive moments in history. And yet, it all coalesces.

Reading Maalouf, one has the impression of sitting comfortably in a room beside him. This story is a deeply personal one for the author. Indeed, at certain points when he circles back to reflect on where he was on one momentous occasion in history or another, it is almost like reading a poignant novel. “The vagaries of my life as a journalist meant that during the Iranian revolution I was once again witness to one of the great upheavals of my age,” he writes under the section “The Year of the Great Reversal,” in which he elaborates on 1979, its significance, and the change in the Zeitgeist of the time. “I use the term ‘witness’ in its most literal sense: when the foundation of the Islamic Republic was announced, I was in a small theatre in Tehran; on the stage in front of me, sitting in a large armchair before the curtain, was Ayatollah Khomeini. It was February 5, 1979, and this strange picture is forever imprinted on my memory.”

His eyewitness accounts imbue Adrift with an intimate feel otherwise absent from ordinary historical narratives; they bring scenes to life. Early in the book, he writes: “I was eight years old when I visited our old house in Heliopolis for the last time,” referring to his mother’s house in Egypt—which the family would be forced to leave on account of mounting pressure on minority Egyptians in the 1950s. Referring to that era’s Egyptian leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Maalouf suggests that his policies caused a mass exodus of the so-called “Egyptianized” communities, some of which had been established for several generations, even centuries, on the banks of the Nile; Maalouf defines these “Egyptianized” exiles as “Syrian-Lebanese, Italian, French, Greek, Jewish or Maltese.” It was no coincidence that all or most of the “Egyptianized” mentioned by Maalouf in Adrift were non-Muslims. Much of the book laments how ethnicity and religion have brought about the downfall of Levantine nations that were known for their tolerance and prosperity until the 1950s.

Maalouf seamlessly weaves personal detail into the historic fabric of his tale: “My mother took me to help pack up some things before we finally abandoned the place for good. My grandmother had just passed away from cancer. The house had been in her name, as was typical at the time, and she sold it on her deathbed to an Egyptian army officer. For a fraction of its value, needless to say, although she made the buyer promise to keep the statue of Saint Teresa that adorned the façade…The officer was true to his word, as were his heirs. As far as I know, Saint Teresa is still there.”

Adrift is pleasantly conversational throughout; Maalouf engages in give-and-take with the reader, posing questions in anticipation of potential rebuttals to his claims, the tone paternal without being pedantic. He writes sincerely, and his heartfelt desire to see the world restored to a state in which the ideals he champions — among which universality and pluralism figure most prominently — is clearly evident on every page. In this regard, Adrift bears quite a striking resemblance to his other work of nonfiction, Disordered World, in which he addresses similar themes and posits that the world is, as the title suggests, “disordered,” debased. Interestingly, the English edition of Disordered World came out in 2011, and Maalouf was afforded the chance to comment on the nascent Syrian Revolution and Arab Spring, which had promised so much potential.

“If there is a lesson to be drawn from the events of 2011, it is that the future does not allow itself to be contained within the limits of what is foreseeable, plausible or probable. And it is precisely for that reason that it contains hope,” he wrote then. With the brutal repression of the Syrian uprising, Maalouf would suffer a disappointment that, in addition to the disappointment experienced by anyone who had hoped that from these events would emerge a better world, seems almost unique to writers with the courage to speculate on the future for all to see. By the time Adrift was written, he would have had ample opportunity to reflect on the extent to which the outcome deviated from that earnest hope he expressed on the written page for posterity: The Syrian Civil War is now nearing its tenth year. “I remember watching the nascent Syrian uprising in April 2011, footage shot at night in which demonstrators marched, and chanted: ‘We are going to heaven, martyrs in our millions!’ A slogan soon echoed in other countries throughout the region. I watched these men with as much fascination as horror. They showed great courage, especially given that they were unarmed while the supporters of the regime opened fire at every demonstration,” he writes in Adrift. Rather than the overthrow of a brutal dictatorship, Syria would go on to see swathes of its territory absorbed into the retrograde Islamic State, and the world would suffer the repercussions of this in the terror attacks that swept across it, proving one of Maalouf’s central tenets: that humanity is inexorably united, for better or worse. The phenomenon of ISIS would also soberingly recall his words in his other nonfiction title, In the Name of Identity: “When modernity bears the mark of ‘the Other’ it is not surprising if some people confronting it brandish symbols of atavism to assert their difference.”

Although he affirms that he is “not one of those who likes to believe ‘things were better in [his] day’,” Maalouf does employ rather strong language that would lend to just such an interpretation of his perspective. “On the Road to Ruin” and “A Decaying World” are just a couple of the phrases he uses to set off sections within the book. Perhaps hyperbolic language is a necessary feature of a tome that attempts such a grand undertaking as that of diagnosing the whole world. Nevertheless, he would be correct in saying that humanity is now facing unique challenges, especially with regard to invasive technology, the rise of AI, and climate change — threats the entire world faces.

Despite the universal nature of his message, there are moments in which it would seem that Maalouf writes for a western audience, as evidenced by attempts to persuade the reader that Arabs are not all that they are often made out to be. Having in the previous chapter expounded upon the phenomenon of Marxism in the Middle East, he writes: “This brief digression about the checkered history of Marxism was principally intended as a reminder of the ‘normality’ of the Arab world, a way of underscoring that it long cherished the same dreams and the same illusions as the rest of the planet. I felt the need to emphasize this point, since the prevailing view of the Arab world today is precisely that of fundamental ‘Otherness.’”

While mine is hardly a criticism of Maalouf’s decision to speak to a western audience (if that is indeed the case and his intention), it is nonetheless tragically telling of the sustained effect of western media exposure, rarely showing anything other than war footage from the region and stereotyped portrayals of Arabs, that an author of Lebanese origin would feel the need to counter this.

Adrift largely succeeds where it showcases Maalouf’s extraordinary ability to establish, through history, the interconnectedness of humanity. To build on his extended metaphor of sea, shipwrecks, and sailing and to borrow an oft-quoted line from John Donne, no man is an island, isolated from the rest. We are inextricably linked, as Maalouf abundantly demonstrates by following history’s trail and roping together its many upheavals to construct a comprehensive picture of the present, thereby also offering a way to reach a solution; knowing how we got here and where it all went wrong is, after all, half the battle. While the book does touch upon some contentious points — the invectives on identity politics can be prickly for those who believe in its merits — it also raises many pertinent questions. What are the real benchmarks for progress on a planet where infinite growth is simply unsustainable? What are the effects of continued fragmentation, even as expressed in the emergence of nation-states? How can Arab countries learn from others that have recovered from devastating conflict, such as Germany or Japan?

Adrift presents a digestible way to approach these issues, while also serving as a timely warning to steer a better course together, as it is our collective future that is at stake.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)