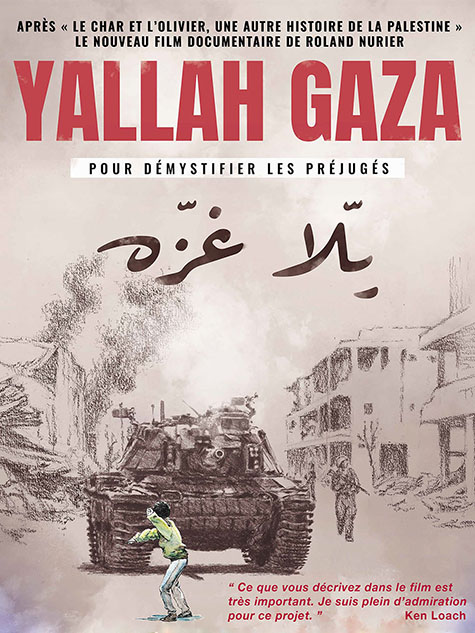

A new documentary on Gaza from Roland Nurier is touring France and screening in diverse film festivals worldwide.

Yallah Gaza! is a documentary in its most classic form, featuring interviews with experts, witnesses and victims of Israel’s years-long blockade and bombing of the Gaza Strip, punctuated by (beautiful) images of the places where the action (or the theme) of the film takes place.

Nurier’s film begins with a factual and somewhat pedagogical statement of the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine at the beginning of the 20th century, followed by the 1948 Nakba and the Palestinian exodus that followed the creation of the State of Israel. The point is clear, the tone is historical.

Jean-Pierre Filiu, professor at Science-Po Paris and Columbia University, undisputed specialist of the Middle East; Sylvain Cypel, journalist at Le Monde newspaper; Mathias Shamali, head of UNRWA in Gaza; and Ken Loach, renowned director, are some of the speakers of the film.

The historical preamble is followed by the contemporary situation of Gazans. We learn that they are an educated people despite the restrictions imposed by Israel and for whom education is a form of resistance.

A little later, Christophe Oberlin, a French surgeon who has been training doctors in Gaza for 20 years, explains the difficulties of practicing his profession in opposition to and under the constant tension applied by the Hebrew state on this tiny territory, especially since January 2006, when Hamas won the elections.

Since then, Gaza has been subjected to a political boycott and an economic blockade.

The film then shifts into a more political mode. The director reminds us that Israel violates international laws developed by the UN, but also the judgments of the International Criminal Court, (Israel is a signatory, but has not ratified the treaty).

The entire film is composed of alternating testimonies of a resilient, courageous Gazan population, without visible hatred towards Israel, and of experts on the region.

There are also images of young people dancing dabkeh amongst the ruins of bombed houses. These sequences exist in the film as a symbol of the resilience of Gazans, of resistance to Israeli violence, of the justified despair of youth.

There are images too, of mutilated children, wounded by Israeli army bullets, who do not complain, who play soccer with crutches, who have even learned to do some acrobatics.

That’s what we see. This is what we are told.

But in Yallah Gaza! everything is told to us, nothing (or very little) is shown to us. Roland Nurier probably spent weeks surveying Gaza, traveled to Gaza, entered Gaza, eaten, slept, talked in Gaza. But little of this human material is delivered to us, and that is where Yallah Gaza! misses its mark. [For a nuanced treatment of Gaza, albeit in a feature film, see Gaza Mon Amour by the Nasser brothers. ED]

In literature, there are a number of terms to define a work that aims to demonstrate or prove a thesis that one defends: factum, diatribe, pamphlet. I don’t know whether any of these words apply to cinematographic works, but in my view, Yallah Gaza! succeeds more as a dialectic than a dynamic narrative; the film reasons with us, but it doesn’t grab us viscerally, because it comes up short in terms of visual grammar.

I felt great frustration while watching a documentary in which the interviews are conducted indoors, framed for television, where the outside images are filmed with a drone (as on television), whereas the director had the eminently fertile possibility of giving us a glimpse of Gaza, from which few images reach us here in the West. We would have had the possibility to think for ourselves, to form our own opinion through cinema.

But where are the images of daily life in Gaza? Where are the scenes of old Palestinians talking together on a street corner or in a café? Where are the moments of family life in Gaza?

They are invisible and inaudible, blurred by the discourse of the interviews and the power of an extra-diegetic music, a score which strives to make the aerial images of a city in ruins excessively epic.

The thesis that Nurier puts together through his experts is certainly implacable, but it reveals nothing new. The film squarely frames Gaza as a victim territory, where its inhabitants’ courage and qualities motivate their survival.

The thought is delivered to us by the words of the protagonists, whom we can believe or not believe, according to whatever opinions we already espouse, but that in any case, the film is powerless to change. One wonders who will be convinced by what Nurier says in Yallah Gaza! Doubtlessly, those who already have the same opinion, but what of the vast majority whose minds may not be made up?

But never mind the probably irreconcilable opinions regarding the Palestinian conflict. What I find objectionable is the position in which Nurier places his viewers. It is a passive position, where it is difficult to discuss the facts as they are presented (are they debatable?). It is difficult not to have empathy for these Palestinian children rendered crippled by Tsahal, or simply by the impossible situation of Gaza, a huge open-air prison, which Israeli jailers observe from the other side of a border that the whole world would like to see abolished, a world that already without this film, shares this feeling of anger.

Here we are faced with the terrible observation of impotence, which only leaves room for anger, and therefore for violence, even if the documentary fortunately refrains from apologizing for it.

Politics takes over here and I refuse to get involved. It is not my subject, even if everyone can have the opinion he wants on the subject.

Nurier has his, I have mine and these two opinions are probably close. Without disputing the reality of the facts that are related, I remain convinced that a filmmaker’s work is different from what Yallah Gaza! presents to us.

Assalam Alaikoum