Can love act as a transformative force during challenging times, in the face of 2000-pound bombs, drones, AI surveillance, snipers, annexation and expulsion?

These days, what was once organized as sci-fi or dystopic fiction is now often found on the Current Affairs or Politics shelves of your local bookstore, such that we ask ourselves, are we awake, or are we dreaming? Should we be more worried about fighting off the vampires, or the zombies? The fact is we live in a war-torn world where the words apartheid, scholasticide and genocide are in common currency — and in which practicing the journalism profession has become lethal in the Middle East. Dystopia? How does Israel answer to the reality that it has killed more media workers in 15 months than all the journalists who perished in WWII and the Vietnam war, combined?

So much for international humanitarian law in 2025.

So, can love act as a transformative force during challenging times? Where is the family in such dire circumstances? And for those fighting the revolution in whatever form, what is the impact of resistance on romantic relationships and friendships? Or the challenges faced by people separated by conflict, whether it is those who remain or those who flee? Does love for one’s country complicate or enhance personal relationships during times of war? But really, what is the power of culture in the face of 2000-pound bombs, drones, AI surveillance, snipers, annexation and expulsion?

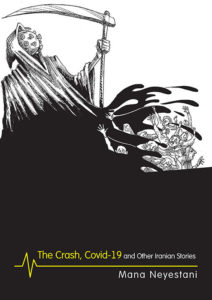

The Markaz Review’s March issue poses far more questions than answers, in essays, fiction, art, photography and even humor, which attempt to make sense of the incomprehensible. In Malu Halasa’s story, “Love and Resistance in Online Persian Dating Shows,” there are unbelievable situations in which dates are blindfolded or threatened with cockroaches. Even as these Iranian YouTube game shows go viral with millions of viewers, the regime takes action to shut them down. Meanwhile in Beirut, visual and cultural anthropologist Sabah Haider visits Dahiye and talks to widows and other survivors of this year’s war between Israel and Hezbollah, in “Heartbreak and Commemoration in Beirut’s Southern Suburbs.” In the imaginative essay from Palestinian filmmaker and novelist Alia Yunis, “A Conversation Among My Homeland’s Trees,” life is seen from the perspective of, among others, the orange, date, and pine trees of Palestine.

Iskandar Abdallah, a refugee in Berlin from one unjust war, attends a protest against another in Gaza, in “Manifesto of Love and Revolution.” Still scarred and reminded of his personal trauma as he witnesses new atrocities, he seeks the only shelter available to him — in love. The Syrian war has cast a long shadow over Syrians, who in fleeing the regime have been scattered around the world. But some of them are connected, whether they know it or not by a lingering emotion, even possibly a love child, as in Anna Lekas Miller’s provocative short story, “The Monster Is Gone.” Both Abdallah and Miller have written previously for The Markaz Review and their new fiction, in Abdallah’s case fictionalized memoir, and in Miller’s a short story that captures the uncertainty of migrants’ lives, they represent a development not only in their own writing, but in the stories The Markaz is intent on publishing.

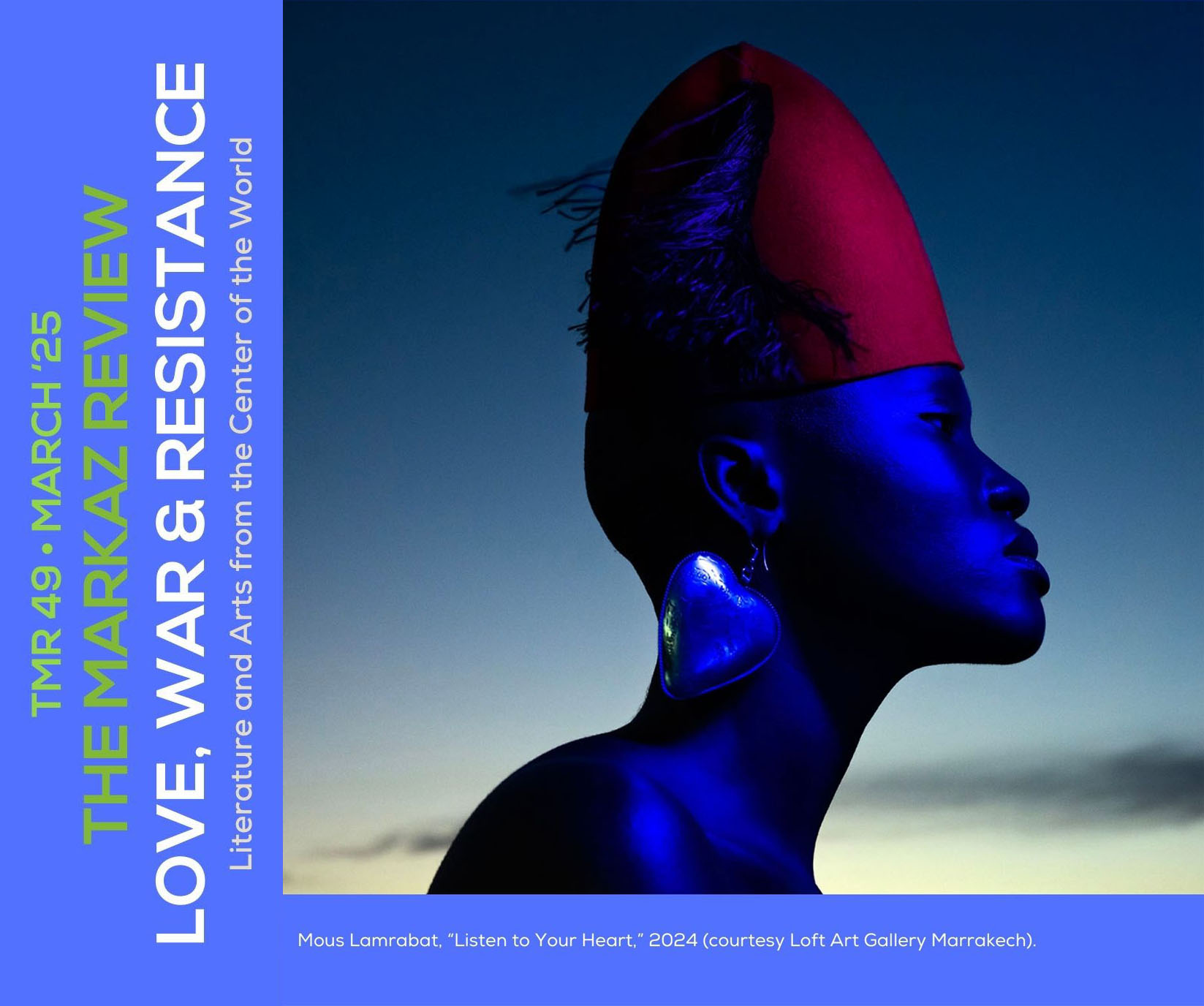

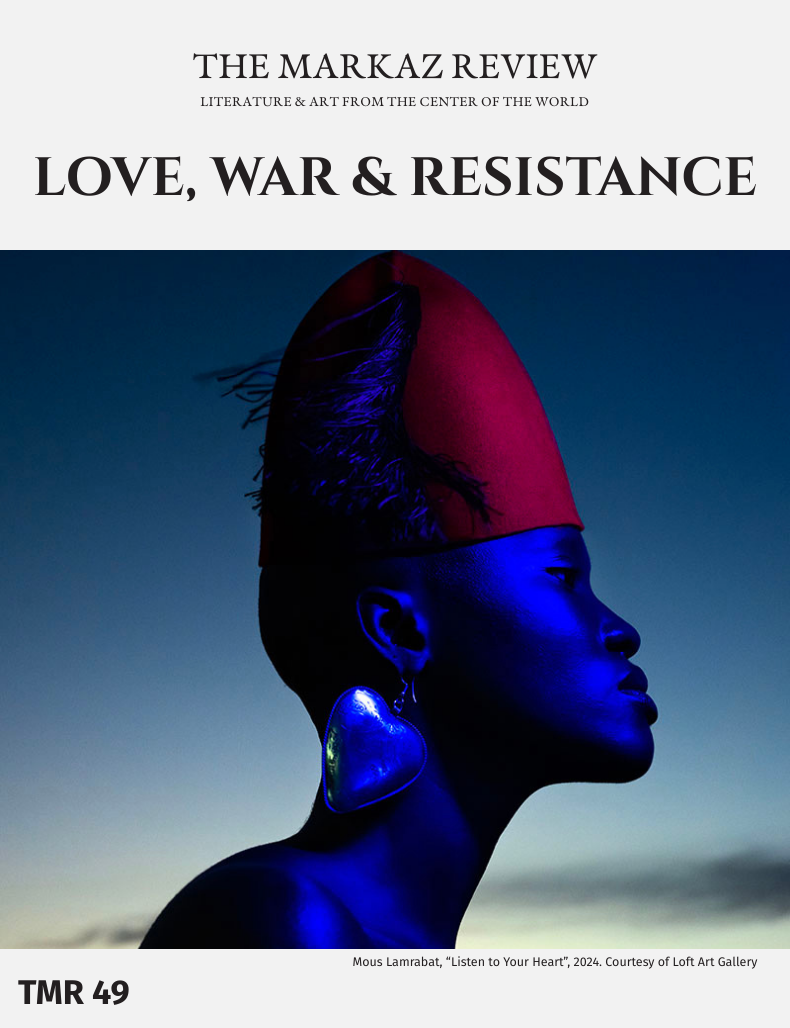

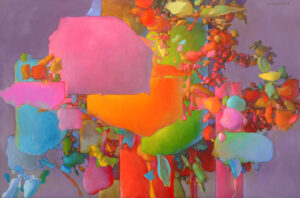

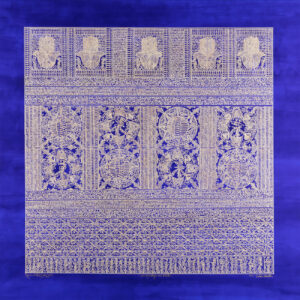

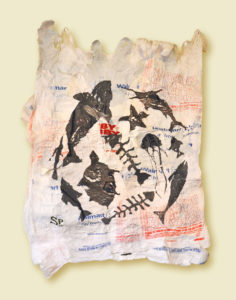

Resistance can come in many forms, as seen by Jelena Sofronijevic review of the British Museum’s War Rugs: Afghan’s Knotted History. Men, women and children, some in the refugee camps designed and wove war rugs — considered some of the best war art of the 20th century. In these, the flowered medallions so typical of “Oriental” carpets had been replaced by Russian soldiers, represented as “White horned divs” or evil phantoms, from the great Persian classic the Shahnameh. This cultural production was produced by internally and externally displaced peoples whose country, lost to them, became populated by foreign soldiers and armaments depicted in the rugs. The issue’s Featured Artist, by Naima Morelli, is the Moroccan-Belgium photographer Mous Lamrabat, whose solo show, Homesick, in Marrakech, explores belonging and identity amid a different kind of loss. In his stark, highly individual, boldly colored fine art photography, he draws from nostalgia and cultural fusion. His is a practice, which sits between fine art and high fashion, and his distinctive photographs have been featured on the cover of Vogue Arabia.

Undoubtedly resistance or rather criticism of powerful institutions can come at great personal cost. Kuwaiti writer Nejoud Al-Yagout tells the story of a woman journalist in the excerpt from her novel, “Hate Mail, Death Threats from When the Haboob Sings.” The protagonist dared to write an article that challenged the religious status quo in an unspecified Gulf country and suffered for it.

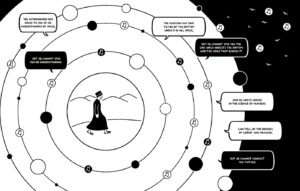

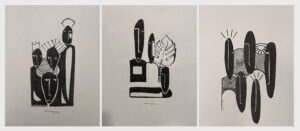

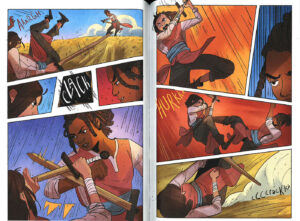

Also featured in TMR’s LOVE, WAR & RESISTANCE’s issue are graphic novels and short stories. Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet is a smash literary hit that has been translated into 100 languages and never been out of print since its publication in 1923. However many Lebanese, like the graphic novelist Zeina Abirached, have always had a love-hate relationship with Gibran’s prose-fables. In the review “Illustrated Intimacy,” TMR critic Katie Logan writes about Abirached’s alienation from The Prophet. Her new, eponymous graphic novel introduces Gibran’s text to modern audiences, through a journey of visual reimagining.

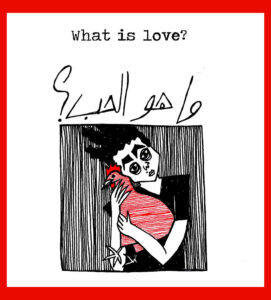

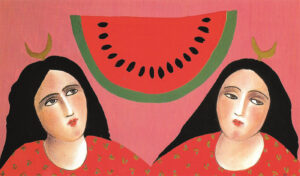

An allegorical love story from the farmyard also comes in the graphic form. Lebanese artist Rawand Issa had seen echoes of her own run-ins with “lover boy rooster” in the 1943 novel Mudhakkarat Dajjajah by the Palestinian novelist Ishaq al-Husayni, first published in Cairo. Issa wrote and drew her story, translated from the Arabic into English by Anam Zafar, and gave it the same title as al-Husayni’s novel, “A Chicken’s Diary.”

Perhaps acts of love as protest in art, literature, and online dating game shows can’t change outright oppression, but creative expressions like these challenge a worldview that says war, apartheid, and mafia-like shakedowns are the status quo. Now in Gaza a younger generation has been turning to art, making it, and taking the first tentative steps on the long, difficult road to becoming artists.

Surely the rest of us should take heart and follow their lead.